Grand botanical publications of the 18th and 19th centuries: from scientific discovery to practical horticulture

By Joan Bruce, Specialist Librarian and Stacey Larner, Librarian | 14 January 2022

After the British established a convict colony in Australia in 1788 a river of botanical specimens began to flow to Europe. Both the scientific establishment and the aristocracy developed a fervour for Australian plants. Eager to please Sir Joseph Banks, early governors were zealous in sending him botanical specimens and sketches by anyone who could wield a pencil.

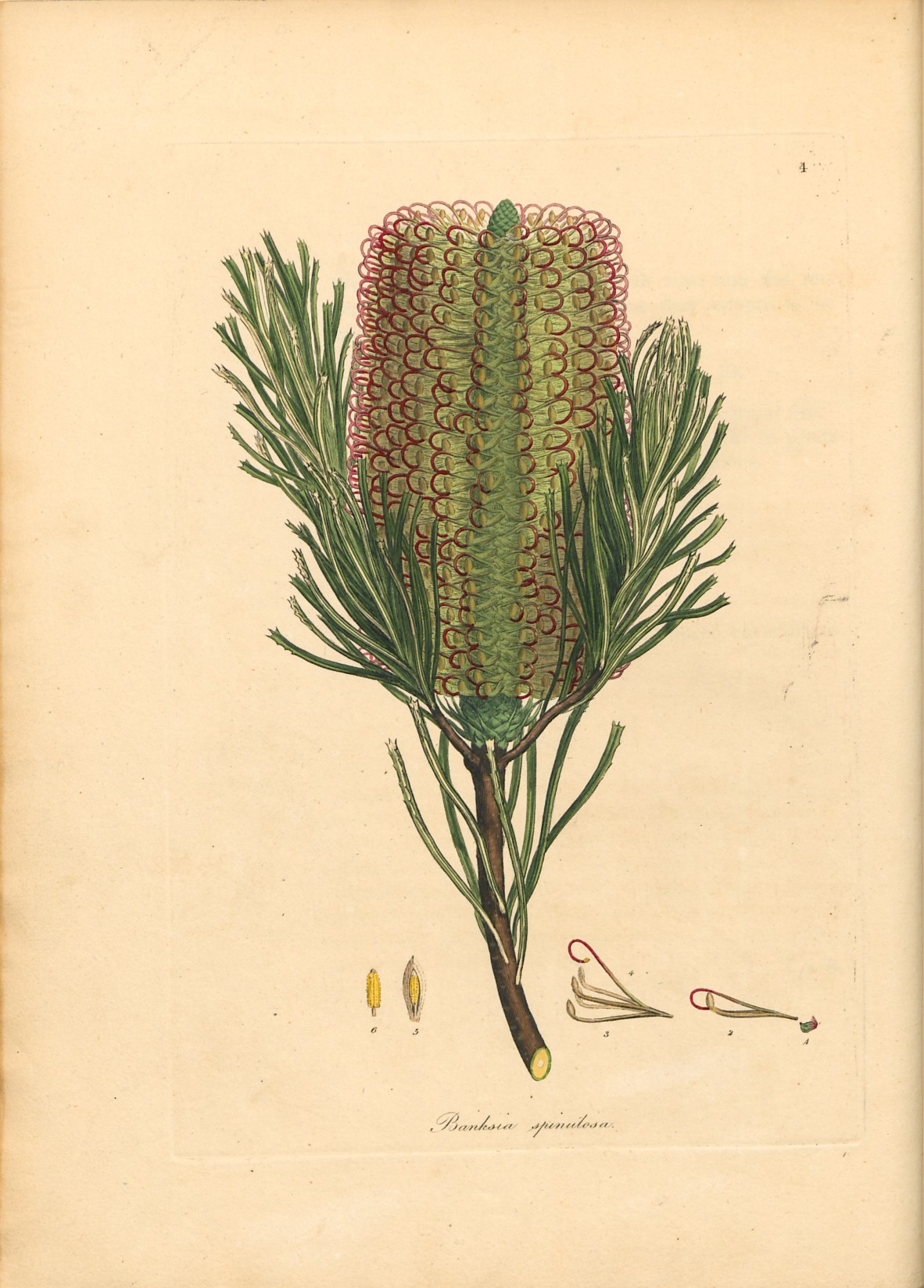

Banksia spinulosa, A specimen of the botany of New Holland, 1793, Australian Library of Art, State Library of Queensland

The European desire for Australian plants created a market for deluxe colour publications. A Specimen of the Botany of New Holland, published in 1793 and illustrated by James Sowerby, was the first publication dedicated solely to Australian plants. Exotic Botany : consisting of coloured figures and scientific descriptions of such new, beautiful, or rare plants as are worthy of cultivation in the gardens of Britain ; with remarks on their qualities, history, and requisite modes of treatment (1804-1805) was also illustrated by Sowerby and incorporated “exotic” plants from across the colonies, including Australia.

Eucalyptus resinifera, Exotic Botany, 1804-1805, Australian Library of Art, State Library of Queensland

Private botanic gardens flourished. After the first decades of the 19th century the fashion for Australian plants was subsumed into a general passion for the exotic. Botanical magazines aimed at private collectors and nurserymen, rather than botanical taxonomists, proliferated throughout the 19th century. Glorious illustrations of exotic flowers accompanied a page or two of information and practical instructions for cultivation.

![Glycine bimaculata [Hardenbergia violacea] 1794 The botanical magazine or the flower garden displayed, Australian Library of Art, State Library of Queensland](/sites/default/files/styles/slq_standard/public/Hardenbergia%20violacea.jpg?itok=JpoHVyZa)

Glycine bimaculata [Hardenbergia violacea], The botanical magazine or the flower garden displayed, 1794, Australian Library of Art, State Library of Queensland

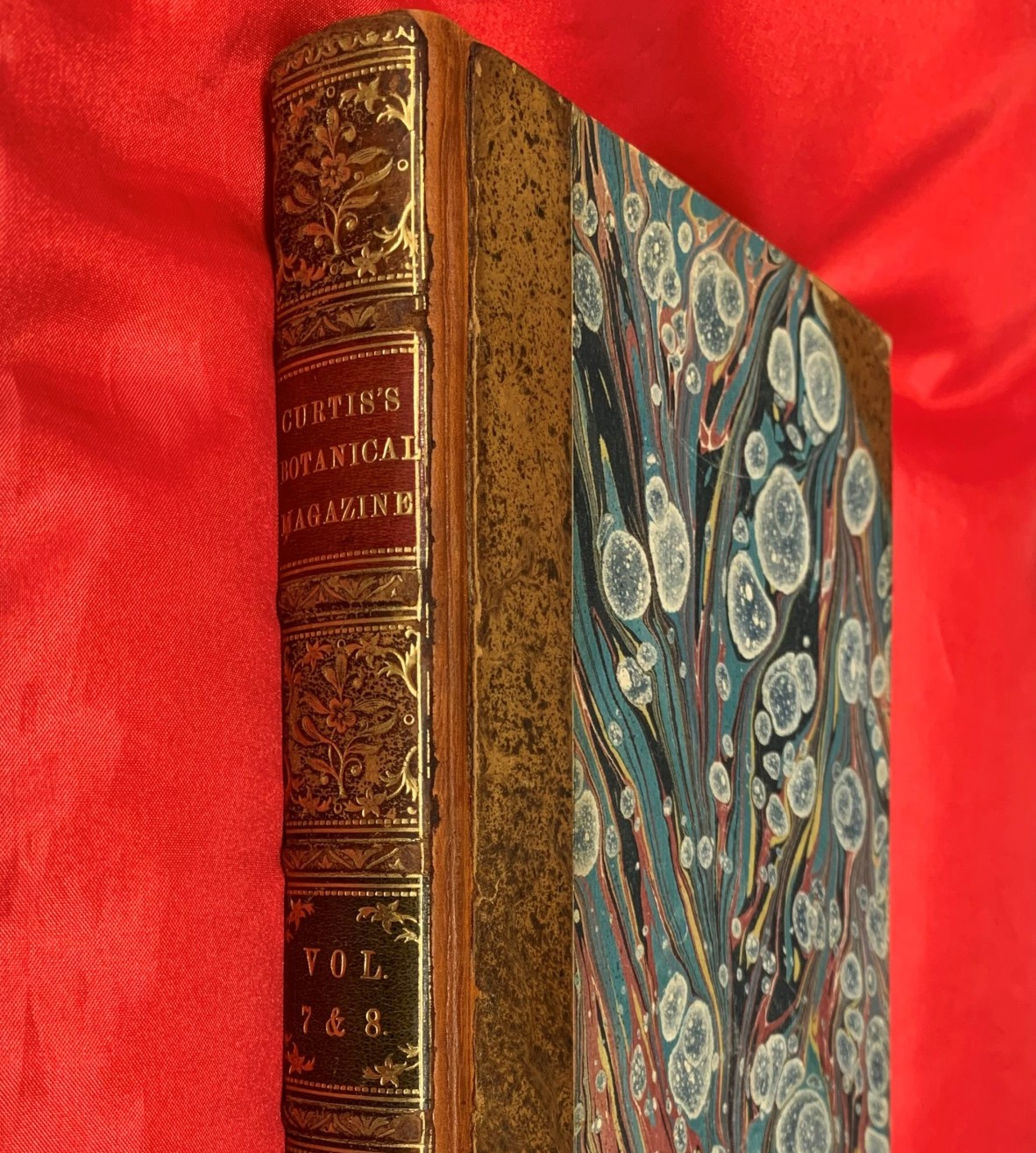

The first issue of The Botanical magazine or the flower-garden displayed in which the most ornamental foreign plants, cultivated in the open ground, the green-house, and the stove, will be accurately represented in their natural colours (also known as Curtis’s botanical magazine) appeared in 1787, during the height of the passion for Australian plants. It has been published continuously ever since. The illustrations were hand-coloured until 1948. Those anonymous hand-colourists were often women. In the years after the French Revolution, many of those were immigrants, using the training they had received in the art of flower painting to survive.

Curtis’s botanical magazine, 1794, Australian Library of Art, State Library of Queensland

Flore des serres et des jardins de l'Europe : annales générales d'horticulture, a lavish sales catalogue for the Belgian nurseryman, Louis van Houtte, appeared in 1845 at the height of orchid mania. It was published for four decades with Van Houtte sending plant collectors worldwide to gather plants for his greenhouses.

Eucalyptus cornuta, Flore des serres et des jardins de l'Europe, 1875, Australian Library of Art, State Library of Queensland.

Harriet Scott's original drawing was used for the giant spear lily illustrations in both the Gardeners' Chronicle and Flore des serres et des jardins de l'Europe. Only a brief mention in the text acknowledges her as the artist, despite the fact she was a professional illustrator. Harriet and her sister Helena were concerned about the social shame of having to work for a living, which may have been why they were not attributed.

Doryanthes palmeri in Flore des serres et des jardins de l'Europe, 1874. Image courtesy Biodiversity Heritage Library – original exhibited in the Entwined exhibition, courtesy CSIRO Australian National Herbarium.

The State Library of Queensland holds a number of grand botanical publications in the collection. These can be viewed onsite at the John Oxley Library, and many are digitised to view online.

Other blogs relating to Entwined: plants and people

- Xanthorrhoeas - An Australian Explosive

- Queensland's fern fever

- Keeping culture alive through weaving

- Orchidelirium: when love turns to obsession

- Queensland’s coastal kidneys: mangroves

- Bountiful bunyas : a charismatic tree with a fascinating history

- The grand florilegiums of Joseph Banks and Ferdinand Bauer

- Queensland’s gympie-gympie: the world’s most painful plant

Comments

Your email address will not be published.

We welcome relevant, respectful comments.