Orchidelirium: when love turns to obsession

By Stacey Larner, Librarian, Queensland Memory | 4 August 2021

One of the most enduring plant obsessions is orchidelirium, or the mania for orchids. This obsession has resulted in theft, death, and environmental destruction, including the apparent extinction in the wild of some species. On the flip side, it has also motivated advances in horticultural techniques and increased scientific understanding of the relationships between fungi and plants.

Dendrobium speciosum, or King orchid, on the cover of The Queenslander in 1931. Climate change threatens the survival of the northern sub-species. John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland.

Initially orchidelirium was a craze limited to the European upper classes. A difficult plant to grow in cold or even temperate climates, the rich spent a fortune on orchids that died in unsuitable conditions, generally with waterlogged roots in stifling hot greenhouses. Orchid-hunters were hired to travel to remote tropical regions of the world, collect orchids and bring them back. It was dangerous work, often romanticised. Many died on these expeditions, from misadventure or conflict with locals, and rival orchid-hunters engaged in willfully destructive behaviours, such as urinating on the plants collected by their rivals after stripping the rest of the habitat bare.

One orchid-hunter recounted his tale in a 1922 article, telling of his terrible ordeal in Papua New Guinea, retrieving a rare and beautiful orchid that was worth £1000 to him if he could send it to a certain collector by the name of Hollick.

The Pool of Leeches, Smith's Weekly (Sydney, NSW : 1919 - 1950), 1 July 1922, pg 3.

Orchids on a cart at Glamorgan Vale, Queensland, December 1921. GL-13 Album of Stereoscopic Views, Image number 7709-0001-0009, John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland.

In Australia, orchidelirium caused similar environmental impacts. In the days before environmental protection, forests were stripped of sought-after species for avid collectors. In 1899, rare orchid bulbs were stolen from the Botanic Gardens in Sydney and the blame laid squarely at the feet of the “well to-do". The image above depicts a cart loaded with orchids taken from the Lockyer Valley in Queensland.

Brilliant orchid growing near the Tinaroo Lake area, 1984. 7435 Ron and Ngaire Gale Collection, Image number: 401-26-05, John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland.

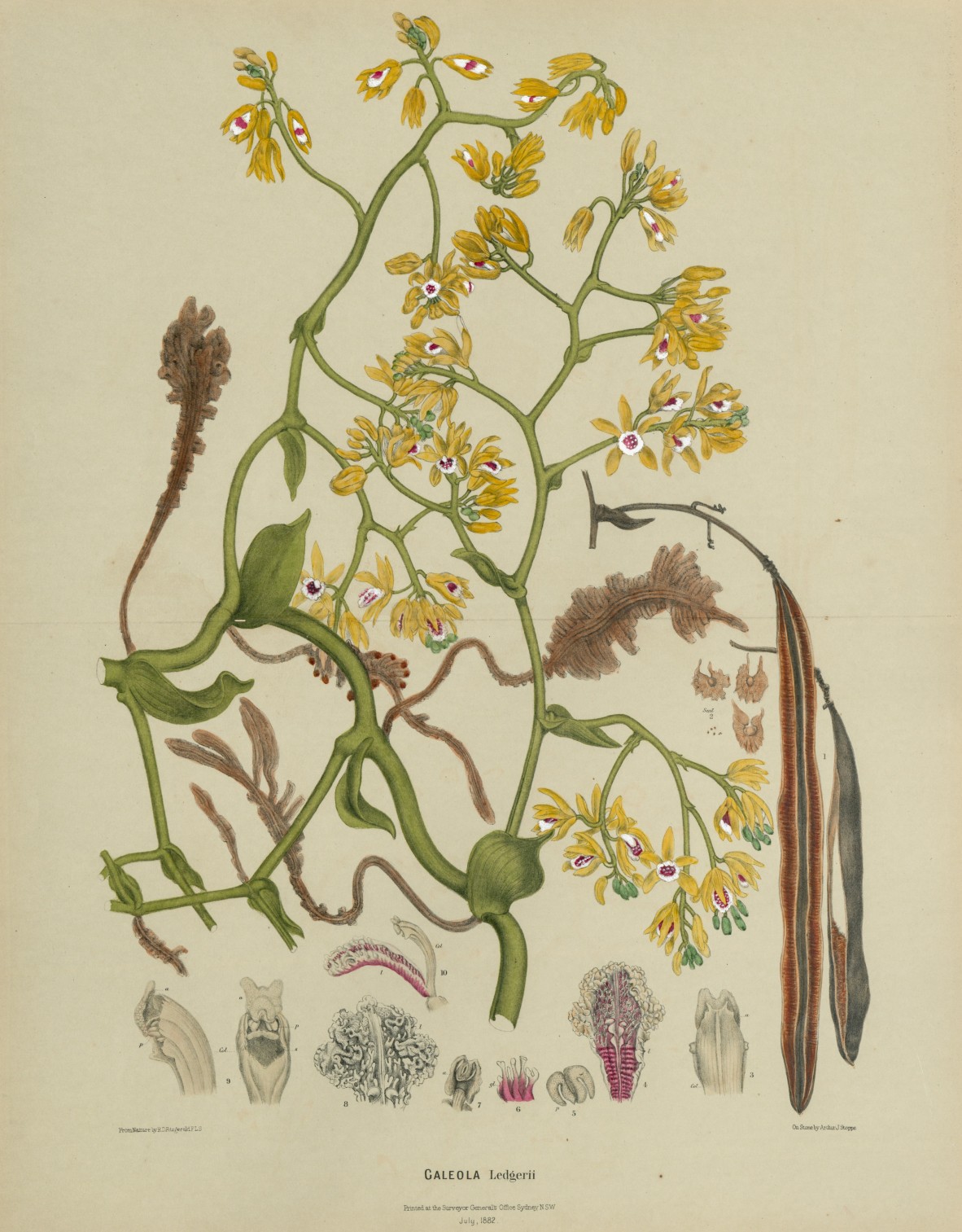

Aside from being beautiful, orchids are fascinating plants. The Great climbing orchid (shown below) is the largest in Australia, with flower spikes up to two metres long and one metre wide. It survives due to a close relationship with fungi, as its ability to photosynthesise is limited.

Galeola ledgerii (now known as Pseudovanilla foliata) in Australian orchids.

RBHMONF FIT, Australian orchids by R. D. Fitzgerald, Sydney : Thomas Richards, Government Printer, 1882.

While it might seem that the ethical issues of the mania are consigned to the past, present-day orchidelirium is fuelling an illicit international trade in new orchid species. According to Mike Fay, interviewed in the Guardian in 2021:

There are documented cases of new slipper orchids having been discovered in south-east Asia in recent years. And, before they’ve even been officially described, populations have been stripped from nature and it is effectively extinct in the wild.

The Cooktown orchid is Queensland’s floral emblem. 7032 Kahlert collection of colour slides, Image number 7032-0001-0097, John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland.

The Royal Botanical Gardens at Kew still grapple with the problem of orchid thievery. 24-hour security monitors the perimeter, and rare orchids are hidden away. No longer limited to expensive horticultural catalogues like the Flore des serres, the reach of social media’s “orchid influencers" are apparently behind the latest craze.

Oncidium crispum, an orchid endemic to Brazil, advertised in volume 21 of Flore des serres. RB 582, Flore des serres et des jardins de l'Europe : annales générales d'horticulture by Louis van Houtte, Gand Belgique : Louis van Houtte, 1845

New orchid species are still being discovered in Australia, though their locations are usually kept hidden. Recently a new species was found in Lamington National Park. It’s in the same genus as the Pterostylis baptistii, pictured below, from Robert D. Fitzgerald’s Australian orchids.

Pterostylis baptistii in Australian orchids.

RBHMONF FIT, Australian orchids by R. D. Fitzgerald, Sydney : Thomas Richards, Government Printer, 1882.

Orchids are featured in the Entwined: plants and people exhibition which is open now and runs until November 14, 2021.

The publication Kindred Spirits: plants and people, the companion book to Entwined: plants and people is available to purchase from the Library Book Shop. With text by Shannon Brett, featuring images from State Library’s collection and more, it explores the ancient and ongoing connection between First Nations people and plants in Queensland. This publication was developed in response to the Entwined: plants and people.

Other blogs relating to Entwined: plants and people

- Queensland's fern fever

- Xanthorrhoeas - An Australian Explosive

- Keeping culture alive through weaving

- Queensland’s coastal kidneys: mangroves

- Bountiful bunyas : a charismatic tree with a fascinating history

- The grand florilegiums of Joseph Banks and Ferdinand Bauer

- Queensland’s gympie-gympie: the world’s most painful plant

- Grand botanical publications of the 18th and 19th centuries: from scientific discovery to practical horticulture

Comments

Your email address will not be published.

We welcome relevant, respectful comments.