‘The Selvage Edge of Civilisation’: Queensland Fiction and Colonial Histories

By Guest bloggers: 2022 John Oxley Library Honorary Fellow Professor Anna Johnston | 15 July 2024

Brisbane 1828-1928, 1928, William Bustard, City of Brisbane Collection, Museum of Brisbane

Guest blogger: Professor Anna Johnston - 2022 John Oxley Library Honorary Fellow

This blogpost reflects on the John Oxley Honorary Fellowship that enabled me to spend wonderful hours reading, thinking, and walking along the Maiwar River. My research focused on nineteenth-century fiction that reveals complex and intertwined First Nations and settler histories.

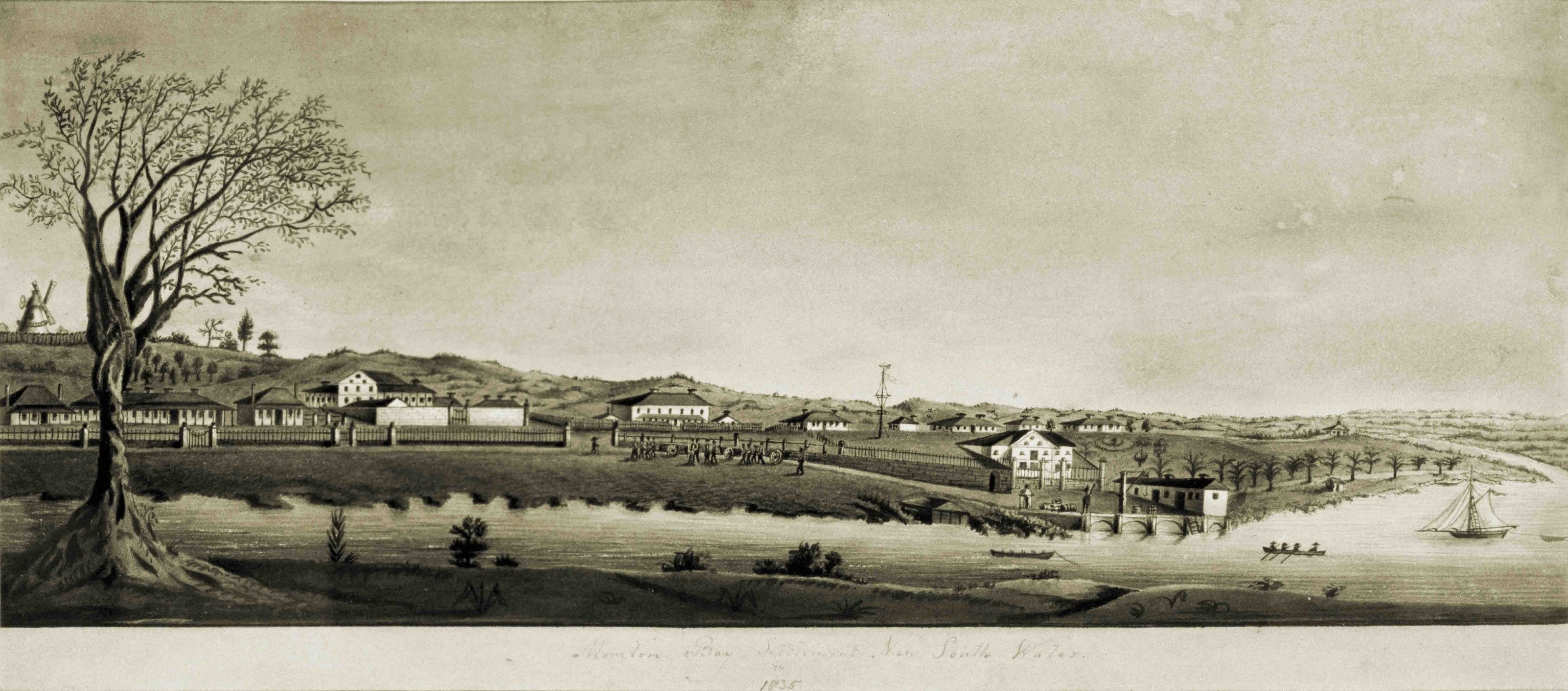

View of Brisbane Watercolour, 1835, Henry Boucher Bowerman, John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland

These writers tried to capture some of the most challenging aspects of colonialism: violence and conflict. Painful histories of violence are connected to these fictional accounts, and they continue to affect individuals, families, and communities. I try to approach this research carefully, with sensitivity and restraint. I have chosen not to share the most shocking passages of writing I have encountered in the John Oxley Library’s books, newspapers, and archives. I have carefully selected some of the images that accompanied the fiction for State Library blogposts because they show how past readers encountered this information and absorbed it imaginatively. I believe that, through a close engagement with these rich and challenging cultural artefacts, we can develop a genuine approach to telling the truth about Queensland’s past.

As a non-Indigenous university researcher and lecturer, I have made a commitment to educating myself about this Country that many people now share. I read widely and deeply in diverse sources, and I pay very close attention to the guidance of First Nations writers, artists, and commentators. I encourage my own students at The University of Queensland to share this commitment. It’s been wonderful to have students who have worked on this project with me write about their experiences. By engaging with our past, informing ourselves, and being truthful about the past and its ongoing presence as memory, I hope we can build a resilient and increasingly well-informed society that can acknowledge complex and sometimes contested knowledge about Queensland’s history. My students’ blogposts show how reading these sources can create positive, future-oriented opportunities to make new meanings from the colonial books, illustrations, periodicals, and manuscripts held by the John Oxley Library. See blog "Fear on the Frontier: Settler Anxieties in Queensland Frontier Fiction"

The Secret River, Kate Grenville (2005). Text Publishing

The contemporary author Kate Grenville described her own commitment to re-write colonial stories when she fictionalised family history in her award-winning novel The Secret River (2005).

Grenville realised that family stories celebrated her ancestor Solomon Wiseman for ‘taking up land’ in the Hawkesbury region after serving his convict sentence, but they did not mention that Wiseman’s land had previously been Indigenous Country and that violence ensued when he selected the land. Grenville took her novel’s title from W.E.H. Stanner’s 1968 Boyer Lecture, which describes a ‘secret river of blood [that] runs through Australian history.’ Grenville explains why she chose to pay attention to the complex and often-violent relationship between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians in her novel:

Until we go back and retell our stories and put the shadows in we won't grow up as a society.

In fact, many nineteenth-century stories and poems explicitly featured these ‘shadowy’ themes of violence and conflict. Our research team identified more than 40 stories and poems published in newspapers and magazines in influential outlets such as The Bulletin, The Queenslander, The Australian Town and Country Journal, The Boomerang, and The Moreton Bay Courier. Christmas editions regularly commissioned original stories by favourite local authors: these expanded issues were intended to keep readers entertained and educated across the summer.

Christmas Supplement, The Queenslander, 19 December 1885

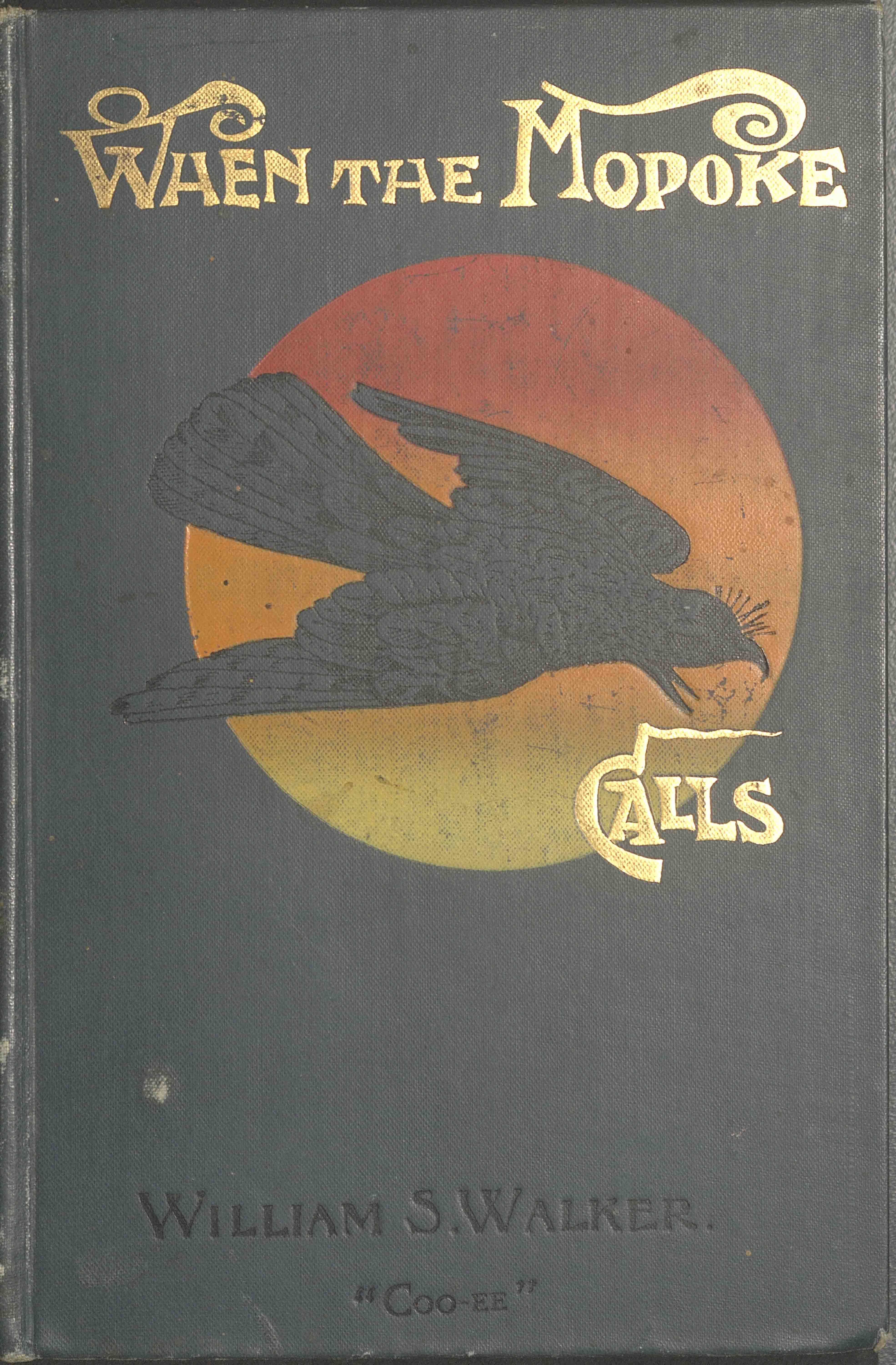

When the Mopoke calls, William s. Walker, 1898. ; with illustrations by Simon H. Vedder. John Long.

The original pieces were often syndicated and reprinted in regional newspapers, ensuring a wide audience both in Queensland and other colonies. Authors who were building their literary career may first have published in local outlets, then subsequently collected their stories and poems together to publish a book-length selected edition (we identify nearly 30 such books).

While some were printed in Australian capital cities, many were published in London, thus expanding the global audience for Queensland-based fiction.

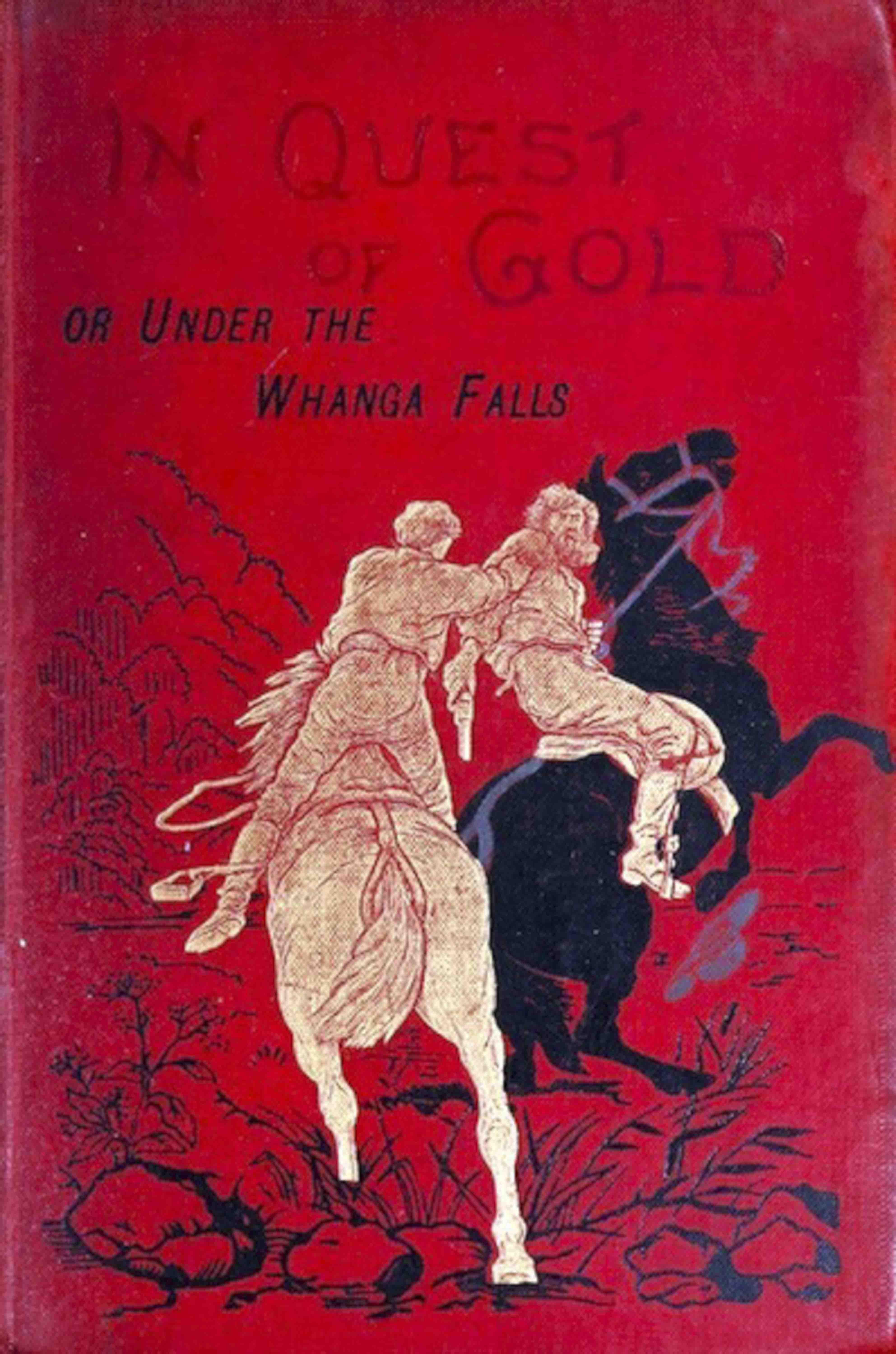

In Quest of Gold, or, Under the Whanga Falls (1885), Kate Grenville (2005). Text Publishing

Some writers were only visitors, such as Alfred St Johnston, a promising young author who toured Australia and the Pacific, writing several books before his untimely death.

His adventure tale, In Quest of Gold, or, Under the Whanga Falls (1885), features two settler brothers Alex and Geordie who go in search of gold to save the family farm after their father dies. Accompanied by two young Aboriginal men, Murri and Prince Tom, the plucky settler boys are favourably compared to their Indigenous peers: even though Alex and Geordie knew much less Latin, history and mathematics than English boys of twelve, ‘they were fine, strong, healthy fellows, with pure and honest hearts’.

This ‘boy’s own adventure’ tale contains multiple examples of violence against Indigenous people. After Prince Tom leaves them to join a local tribe, the brothers are involved in a fight that sees the killing of 12 Indigenous people as well as their former companion:

Geordie fires ‘as coolly as though aiming at pigeons.'

Later, the brothers destroy a dam, killing five Aboriginal people and leaving one gravely injured. However, upon seeing bodies ‘dead and mangled among the stones’, Geordie laments the ‘awful’ sight and dreads ‘to think that [they] killed those five men’. The brothers later debate the proposition that Indigenous people 'deserve equally to be shot with [dingoes and snakes]' and Alex expresses regret for being 'such a brute' to a captured Aboriginal man.

St Johnston provides a dubiously moral ending to a tale that elsewhere provides lurid details of such violence and seems to advise young men that this is a natural part of colonial experience.

‘He seized the native round his slim, naked body,’ , In Quest of Gold, or, Under the Whanga Falls / by Alfred St. Johnston, (1885), p. 79.

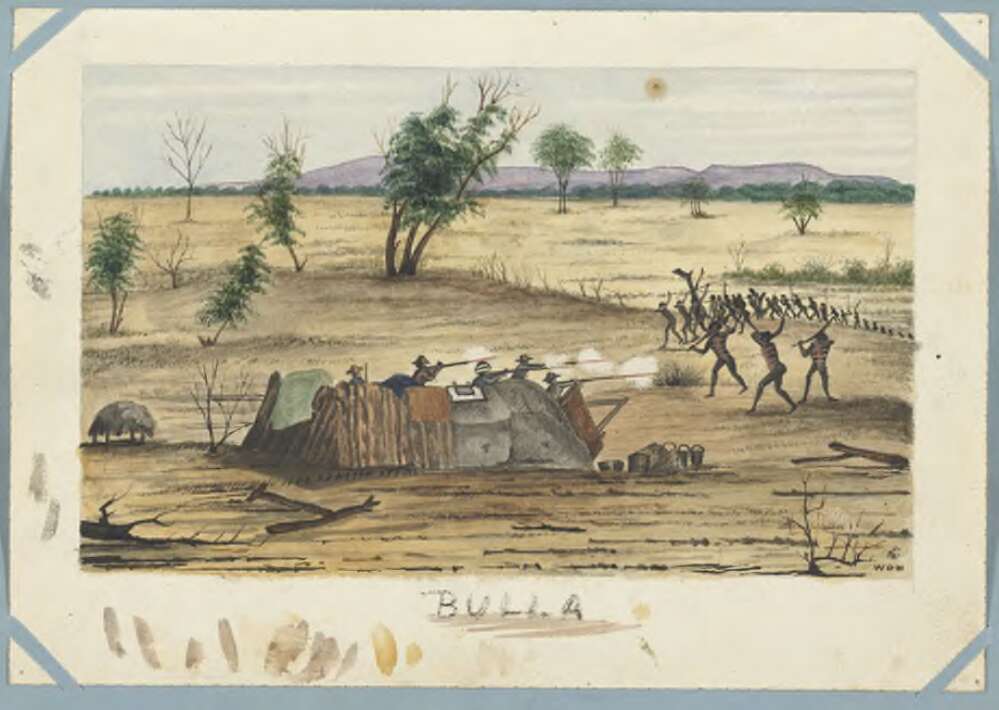

Other authors were amateurs who used writing alongside other cultural forms to record their experiences in the colonies. William Oswald Hodgkinson’s painting provides an eyewitness record of armed conflict at Bulloo in 1860-61.

Bulla, William Oswald Hodgkinson, Bulla, 1861 National Library of Australia, nla.obj-147606769-1

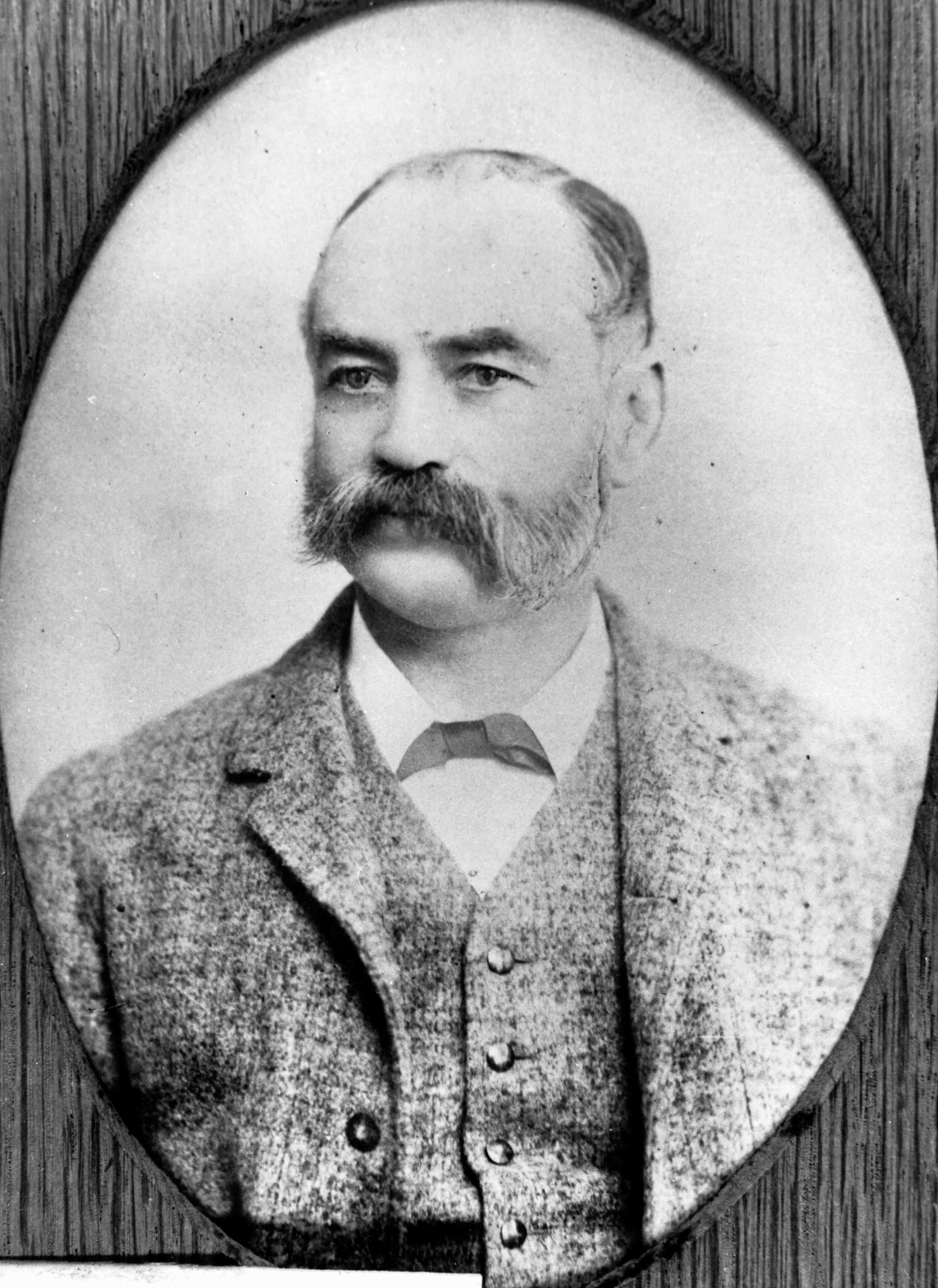

William Oswald Hodgkinson Portrait, Lome, (n.d), John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland. Negative number: 103442

He was the second-in-command on the McKinley expedition in search of Burke and Wills, having previously served as an assistant on the original expedition. Hodgkinson gave his watercolour to Miss Eliza Younghusband in 1861. This was likely a romantic gesture given that William’s image, pasted into Eliza’s album, was accompanied by an original poem that concluded:

Believe me when I say

Your compass towards hearts’ warmest chords

Will point while I’m away.

However, he did not return to South Australia, instead marrying the Queenslander Kate Robertson and becoming editor of the Rockhampton Morning Bulletin.

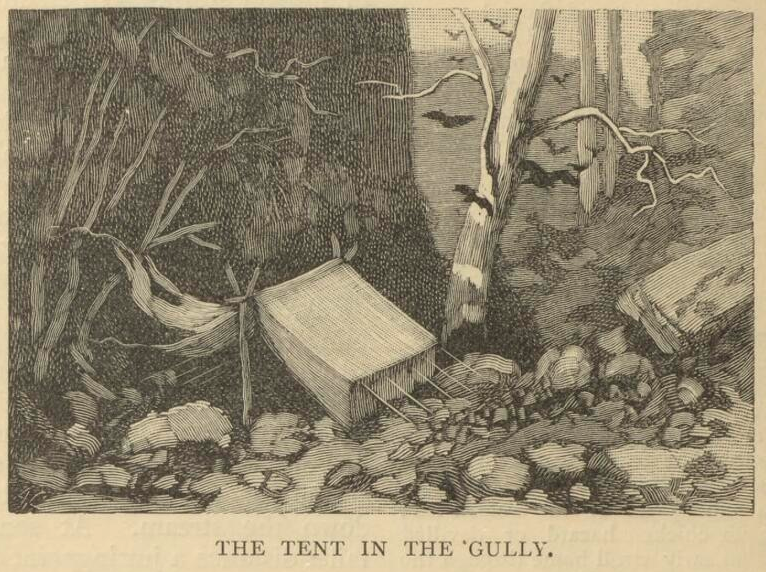

Hodgkinson also dabbled in fiction. His story ‘The Last Chapter’ (1889) follows a settler tracking the killers of an anonymous prospector at Gilbert River in far northern Queensland. The narrator is alerted to the crime by the prospector’s Aboriginal guide Pompey, who brings him a fragment of a sentimental letter that the ill-fated prospector had been writing; his final words are marked by ‘a clot of blood—which stood out in crimson relief and cried revenge.’ With the assistance of Pompey, the narrator and his Aboriginal guides Tin Can and Johny Cake find an abandoned tent and the bloodied, dismembered body of the prospector.

The Tent in the Gully [picture] ‘The Last Chapter,’ William Oswald Hodgkinson, The Centennial Magazine, 11 June 1889, p. 776. NLA.

As you’d expect from his painting, the landscape is crucial in Hodgkinson’s tale of the frontier; indeed, the Queensland landscape as a setting seems to induce brutality and violence in white people. (This idea is shared by A.J. Vogan in The Black Police: A Story of Modern Australia (1890), where a new gold-rush town in Central Queensland is described as ‘The Selvage Edge of Civilization.’) When the team successfully track the killers, the narrator’s ‘civilised’ self is consumed by ‘the lust of the Berserker’ and he leads a brutal attack on an Aboriginal camp at dawn. Despite the disproportionate nature of the revenge killing, the story is brought to an emotional close when the party find a ring among discarded belongings in the camp.

CHH, Portrait of a Woman, ‘The Last Chapter,’ The Centennial Magazine, 11 June 1889, p. 778.

As readers, we are encouraged to assume the ring belongs to the prospector. Some versions of the story conclude with a portrait of a young woman presumed to be the prospector’s now-bereaved sweetheart:

Then the tale was clear, the story was complete, the letter translated, the “last chapter” of a noble life was closed. And this was it. Only a woman.

Here we see how violence and romantic love are intertwined in fiction about colonial life. See blog "Fear on the Frontier: Settler Anxieties in Queensland Frontier Fiction"

These two examples reveal some of the range of writers we identified in the research project: authors, journalists, and editors, who were also involved in business or colonial administration. They collected stories – or drew their own experiences – and re-made them into fiction that sought to explore the murky moral and human conditions of the colonial situations in which they lived or travelled. Fiction provided a discrete veil that could shield individuals’ identities and the precise locations of conflict, but many readers of the time would have been able to deduce or substitute real life experiences of frontier violence that either they had experienced personally or had been told about through family stories or on the bush telegraph.

Some of these stories questioned the ethics of violent ‘dispersals’ of Indigenous people, as I have noted in an early blog. Those authors explored how violence degraded morality in ways that challenged settler ideas about their own racial superiority and undermined the ‘civilisation’ they claimed to bring to remote areas. Yet even stories that are critical of violence stereotyped their Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander characters. As the Goorie novelist Melissa Lucashenko writes,

Aboriginal people have been scrutinised and written about by outsiders in terms both simplistic and racist. … [They] either justified – or at best simply refracted – racist attitudes about the taking of Aboriginal land and the stealing of Aboriginal lives, labour and freedom.

The racist attitudes and derogatory language of some of the colonial sources makes them hard reading. Some might consider this history so shameful that retrieving such stories seems ill-advised. I suggest that unless we acknowledge the prevalence of contemporary accounts of violence between settlers and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, we are not telling the truth about Queensland’s past, or we are only telling it partially in ways that reflect well on dominant society and our own contemporary values. We need to grapple with the fact that this knowledge was public, popular, and widely consumed across ages, genders, and classes, as revealed by the fictional works identified in this project. This is not a question of ‘Why weren’t we told?’ to borrow the title of historian Henry Reynolds’ memoir (2000). It is, rather, to ask how we can account for past knowledge in ways that lead us to better-informed and more just futures?

Edenglassie, Melissa Lucashenko, 2023, UQP.

Fiction provides ways to explore ideas, emotions, and narrative settings with some distance and with empathy. Novelists often show society possible ways forward that are only just imaginable. When Melissa Lucashenko discusses the process of writing her historical novel Edenglassie (2023), she describes her process of seeking knowledge within Yagara and Yagumbeh communities, and in the colonial archives. Many of her colonial sources overlap with those in my John Oxley Library Honorary Fellowship project.

I learnt much by teaching Edenglassie for UQ’s Australian Literature students in 2024. The novel could have dwelt on narratives of suffering and details of the traditional culture that was violently disrupted as colonial governance overtook Indigenous Country. But Edenglassie encourages twenty-first-century readers to consider an alternate version of how colonisation could have occurred, imagining respectful and properly mutual approaches to land selection such as negotiated between traditional landowners and the settler Tom Petrie in the novel, based on Indigenous knowledge and informed by Tom Petrie’s Reminiscences of Early Queensland (1904)

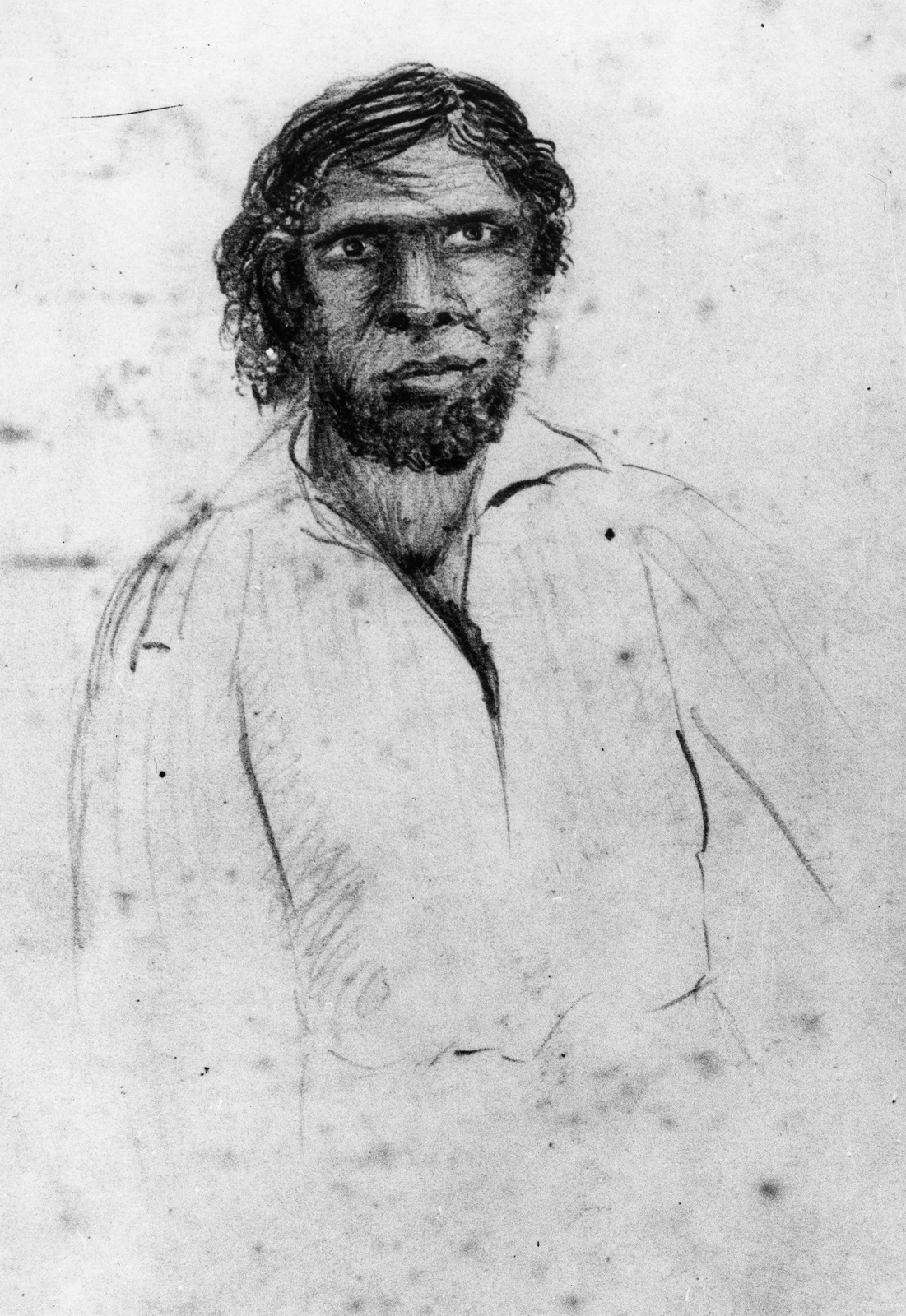

Sketch of Aboriginal Australian Dundalli, Queensland, 5 December, 1854, John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland. Negative number: 11307

The nineteenth-century sections of Lucashenko’s novel explore an alternate history of Queensland’s colonisation (there is also a compelling contemporary narrative including a parallel love story). Edenglassie’s First Nations characters and their story world are based in historical instances such as the Yuggara man Dundalli, hanged for his violent resistance to colonialism in 1855.

Readers can imagine how the public execution at Queen Street Gaol affected Aboriginal observers via the novel’s reconstruction of this key event in Magandjin / Brisbane history.

The novel includes a massacre based on historical violence against Goori villages. Rather than providing an explicit account of the conflict, Lucashenko focusses readers’ attention on the effects the devastating loss of family has on her lead character Mulanyin.

Lucashenko explains how the history of Kipper Billy helped her to write Mulanyin as a profoundly believable young man whose fate readers follow with our heart in our mouth, desperately hoping for his capacity to endure conditions we know are hostile. That hope and empathy, even in the face of terrible knowledge, is how we can let light back into the colonial archive so that we can see its information clearly and account for it honestly.

Recognising and remembering the past can build shared communities and values. We can make new meanings from the cultural artefacts of a shared and painful colonial past, such as the sources identified in this project. These include ways to account for a long and complex tradition of co-existence that underpins Queensland’s ever-evolving modern forms alongside Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander ways of being and knowing. Perhaps, as Melissa Lucashenko suggested at Brisbane Writers Festival in 2024, that includes challenges such as reconsidering the names of Queensland’s cornerstone cultural institutions, including the John Oxley Library itself. Learning to read and think carefully, while creating the conditions for respectful discussion and mutual learning, are to me the best way forward.

Professor Anna Johnston.

More blogs by Professor Anna Johnston:

Comments

Your email address will not be published.

We welcome relevant, respectful comments.