Fear on the Frontier: Settler Anxieties in Queensland Frontier Fiction

By Jessica Creevey and Anna Johnston, 2022 John Oxley Library Honorary Fellow. | 17 June 2024

Guest blogger: Jessica Creevey and Professor Anna Johnston - 2022 John Oxley Library Honorary Fellow

Users are advised that this article contains Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander material that may be culturally sensitive where annotations and terminology have been used from an era at time of creation and may be considered inappropriate today. Material may also contain images, voices or names of deceased persons.

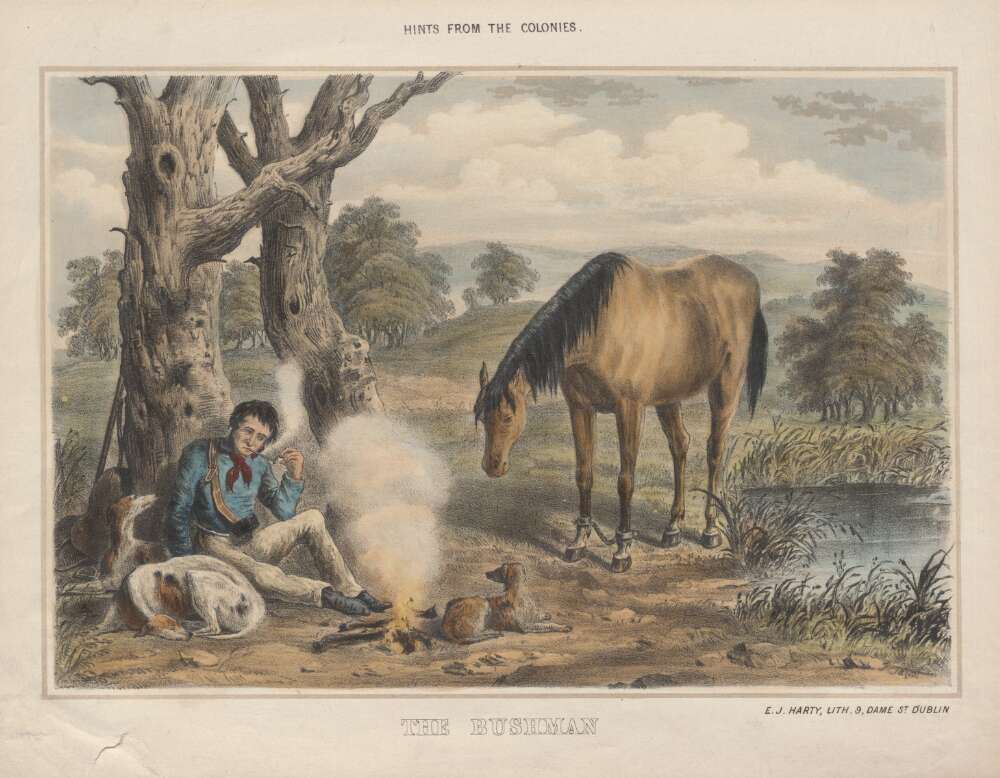

Australia’s sprawling bushlands and desert landscapes have long been a unique aspect of the nation’s character. The archetypal bushman originated in the nineteenth century to distinguish Australian identity from traditional British ideals and has defined the national legacy into the twenty-first century (Cahir et al 4).

Hints from the colonies, the bushman, Harty, E. J. (185-?]), National Library of Australia, Trove.

The outback and scrub are still seen as the natural home of the frontier bushman, and by extension the most obvious location of our national identity (Cahir et al 5). However, the fictional stories within Professor Anna Johnston’s John Oxley Library Honorary Fellowship project History and Fiction: Mapping Frontier Violence in Colonial Queensland Writing reveal how European settler anxieties permeated the vast Queensland landscape throughout the years of frontier warfare. Instead of a comfortable site for settlement, land is a site of conflict in these stories, which reveals the fear that such violence engendered in the colonial imagination.

Set against the backdrop of frontier conflict, many of these stories follow settler characters as they navigate through the bush landscape. In writing these stories, authors often projected their characters’ anxieties about attacks by Indigenous people onto their surrounding environment. William Hodgkinson’s narrator in ‘The Last Chapter’ (1889) tracks through the wilderness alongside Indigenous guides Tin Can and Pompey to find and take revenge upon an Indigenous group who killed an anonymous prospector. He describes the Queensland bushland as a location that invokes violence:

it is a ‘wild and eerie scene’ where the trees offer ‘no welcome shade’ and an ‘oppressive solitude’ is felt.

The narrator battles against the severe summer weather:

‘fearfully hot, the creeks all flooded.’

Through his anxious, haunting description of ‘the cold dead ashes of the fire…ghastly white,’ he associates fires with an absent yet threatening Indigenous presence. These descriptions convey his feelings of weakness against the unpredictability of a non-European landscape.

Travelling photographers' bush camp, Acc 5692 Brier Photographs, Reckitt & Mills, 2005, John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland. Record number: 99183857416902061

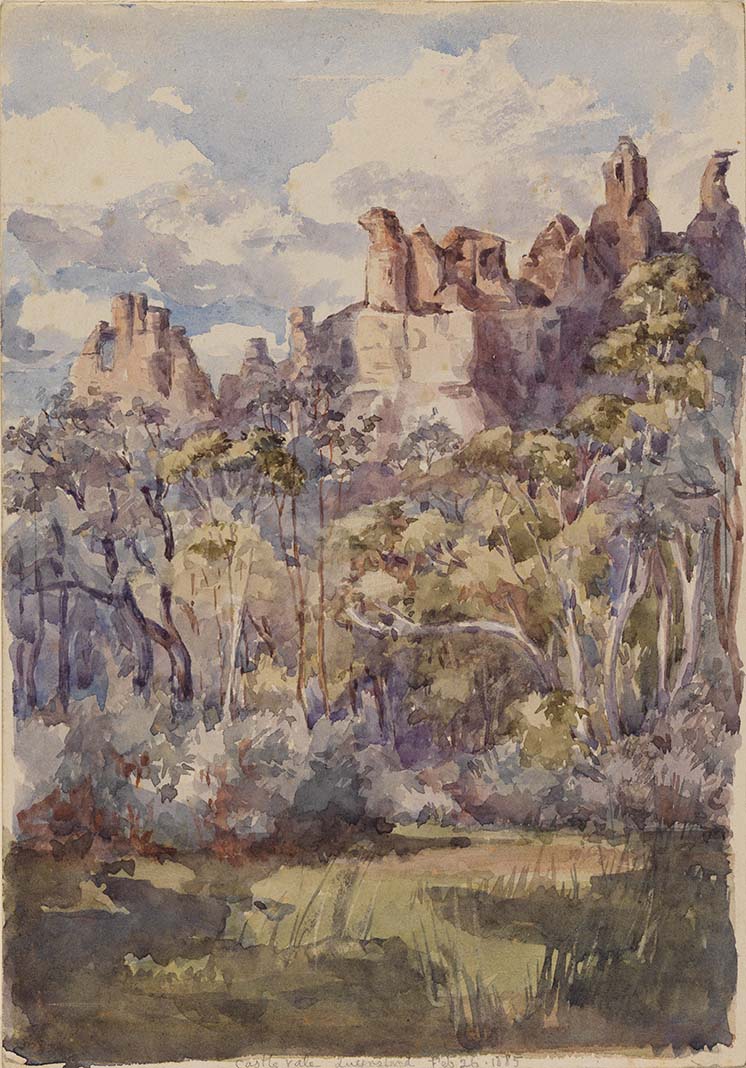

Many characters compare natural structures to those of ‘Old-World’ civilisations. Hodgkinson imagines kingdom structures, with ‘castles, battlements,’ in the bush.

Castle Vale 1885, Neville-Rolfe, Harriet Jane.1885. Accession No: 1:0982, Collection: Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art

He attempts to find something European and familiar in the landscape, while also remaining apprehensive about potential conflict. Similarly, after claiming that ‘human life was not always too secure,’ the narrator in John Mackie’s ‘Kiara’ (1886) describes the mountains on Yukulta/Gangalidda and Garawa Country as ‘vast pathetic pillars of some ruined temple’. By comparing the land to a former civilisation, Mackie’s character emphasises the emptiness of the desert while fearing the return of people and conflict. Both descriptions demonstrate settlers’ constant awareness of Indigenous people’s intimate knowledge of the land. These frontier bushmen were ultimately intimidated by and unwelcome on the land with which they sought to identify.

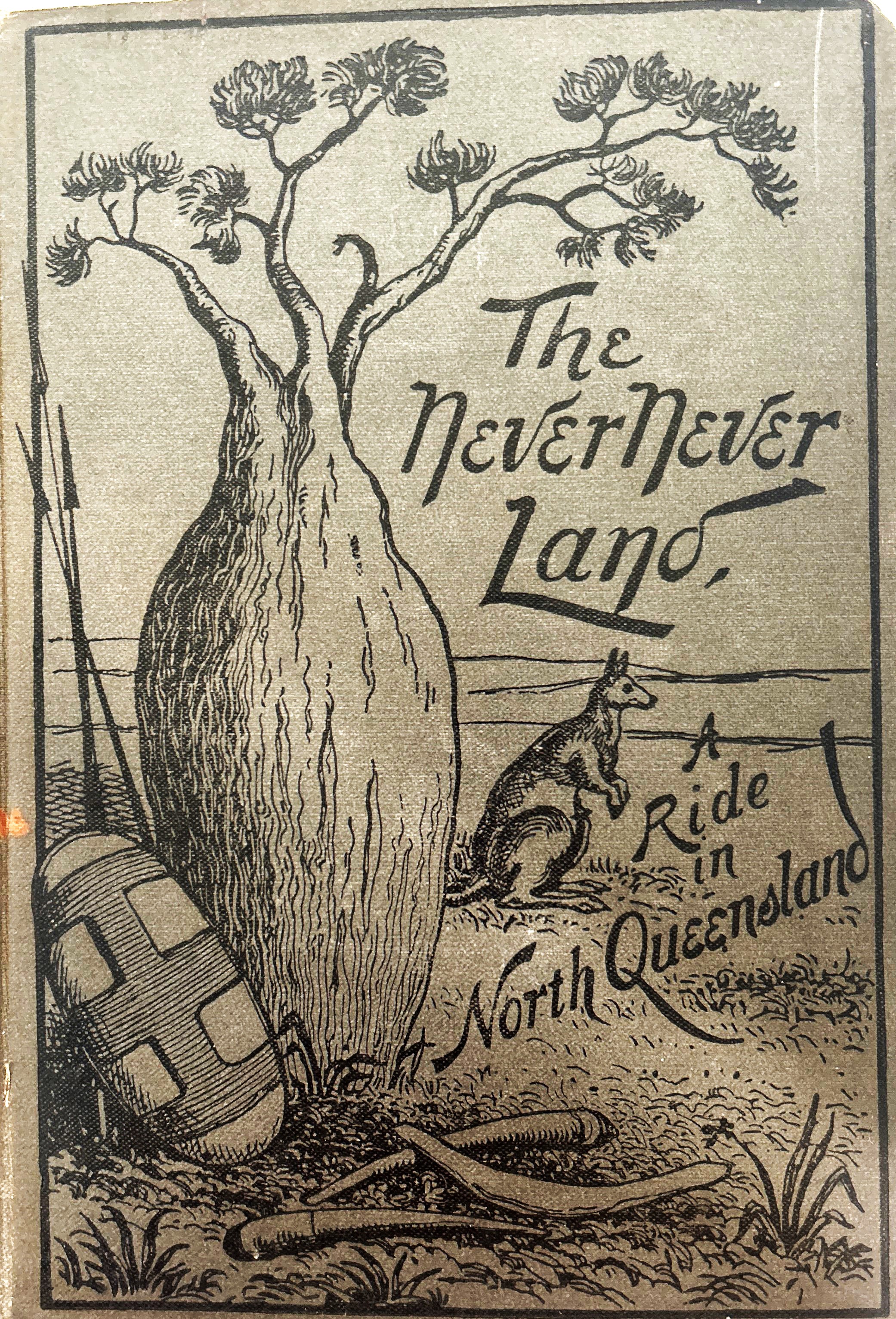

Notably, the outback landscape is commonly described as the ‘Never-Never’. Upon first glance, the term ‘Never-Never’ itself appears to describe a ‘no man’s land’. The earliest written reference to Queensland as the ‘Never-Never’ is in Archibald William Stirling’s novel The Never Never Land: A Ride in North Queensland (1884), which follows his travels around North Queensland.

The Never Never Land: A Ride in North Queensland, Stirling, A. W., Sampson Low, Marston, Searle, and Rivington, 1884. John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland.

Stirling details the lack of knowledge held by Brisbane residents about the state north-west of Rockhampton, or Darumbal Country (Stirling 61).

Some locations were regularly described using the non-specific term ‘Never-Never’. Yukulta / Gangalidda and Garawa Country on the Gulf of Carpentaria (and on the modern borders of Queensland and the Northern Territory) is one such place. In 1885, sixty Indigenous people were massacred at Calvert Downs within this country (Ryan et al 2022). This was reportedly justified by the description of Indigenous people in the region as ‘Quite cheeky, killing cattle and horses within a few miles of the camp’ (Ryan et al 2022). Following the 1886 massacre of fifteen Garrawa people at nearby Wollogorang Station for similar reasons, the region’s stockmen were described as ‘Rough hard cases…taking the law into their own hands.’ This demonstrates a growing perception of local Indigenous people as unpredictably violent (Ryan et al 2022). In 1892, Creswell Station workers George William Clarke and station cook Charles Deloitte were murdered by Indigenous workers Monkeyboy and Walter, leading to two retaliatory massacres of 60 Indigenous people at Corella Creek and Fish Creek (Ryan et al 2022). Retaliatory massacres were deemed necessary to curb Indigenous attacks but they also strengthened settler anxieties about possible unprovoked violence when travelling. The repeated use of the term ‘Never-Never’ suggests that settlers constantly feared conflict because of their isolation and the inherently violent nature of the region.

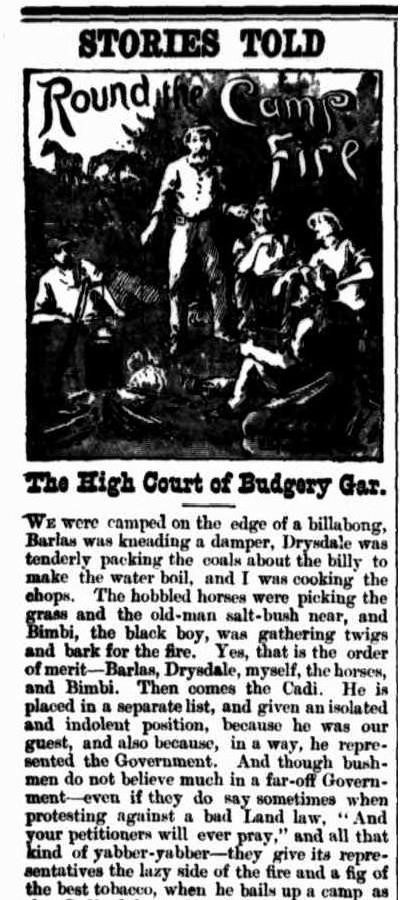

Gilbert Parker explores the perceived ignorance of city folk about violence in the Gulf Country in his story ‘The High Court of Budgery-gar’ (1892).

STORIES TOLD (1892, October 25). The Western Champion and General Advertiser for the Central-Western Districts (Barcaldine, Qld. : 1892 - 1922), p. 3.

The newly appointed magistrate Stewart Ruttan suggests that Indigenous people should be tried for their crimes before the Courts of Law rather than facing revenge killings. In response, the bushman Barlas explains the absence of law in the violent conflict in the Gulf:

‘You don’t know what it is to wait for the law to set things right in this Never Never Land.’

Parker’s narrator describes the country to the west:

‘It was lonely, but surely it was safe. Yes, perhaps it was safe!’

When the bushmen find the humanitarian magistrate murdered, they enforce a bloody revenge.

‘Kiara’ is similarly located in the Gulf, and Mackie too describes it as the ‘Never-Never’. Mackie portrays an ‘old-world air of death’ characterised by ‘[dying] monstrous vegetation’ and limited signs of life. Mackie set his story ‘Faced by Australian Savages’ (1907) nearby, at Calvert River (then Van Alphen River). Here, the ‘Never-Never’ is an enemy striking Mackie’s narrator with a fever curse, which debilitates him and leads him to madness and ‘evil thoughts’ of suicide. These grim frontier writings of the ‘Never-Never’ reflect the sense of colonial powerlessness over the unfamiliar landscape with impending anxiety about Indigenous conflict.

Historical accounts from Australian frontier settlers reflect similar anxieties about Indigenous conflict and presence stemming from the landscape. Richard N. Price reveals that some pastoralists’ experience on isolated sheep runs significantly heightened their fears of Indigenous conflict, based on beliefs that Indigenous people were concealed amongst the seemingly barren farmland (Price 31). Settlers evidently felt that the strong Indigenous connections to land created a power imbalance, as many felt exposed ‘in an enemy’s country’ (Price 32). These prevailing feelings of insecurity, Price argues, suggest that settlers viewed themselves as victims enduring a Hobbesian state of nature, whose lives would be solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short (32).

For both fictional and non-fictional settlers, fortification was their strongest weapon to counter Indigenous land knowledge. Fortified buildings asserted European cultural and physical domination while also providing protection against Indigenous attacks. Mentions of ‘loop-holes’ are found in all primary accounts of fort structure (Burke et al. 35). These small, circular holes functioned both for surveillance and to place rifles through, for example at Yandina Creek Station on Gubbi Gubbi Country (Burke et al. 35-36). Other features included barricades, mud or stone walls, commanding positions, water towers, stockades, refuge rooms and wire netting across windows (Burke et al. 34). Over half of these fortified structures were huts and homesteads on cattle runs (Burke et al. 33).

This is the case for Michaelmas Hut in Nathaniel Walter Swan’s short story ‘Two Days at Michaelmas’ (1872). Located in the fictional town of Warrekerro at Guineago Creek, Swan’s description of the ‘silent land’ and indications of ongoing conflict with Indigenous people imply a ‘Never-Never’ setting. New hutkeeper Hugh Hardy notes a ‘strange sort of oppression’ felt by settlers in the house – a fear further displayed through the requirement to carry a gun at all times.

Sedgeford Outstation on the Alpha Run, Neville-Rolfe, Harriet Jane, 1884, Accession No: 1:0969, Collection: Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art

In contrast, Swan personifies Michaelmas Hut as having a ‘bold, devil-may-care look’, standing ‘red and confident’ and ‘lying in ambush’. This demonstrates the use of forts as a kind of armour to conceal settler anxieties.

Many frontier authors used vivid descriptions of the Australian landscape to create bush gothic narratives, transporting city readers to an unfamiliar and unpredictable world. Despite the often-dramatic nature of these writings, they held true to the emotions of settlers navigating a foreign land, consumed by the possibility of violent retaliation by Indigenous people whose country they were colonising.

More blogs by Professor Anna Johnston:

References

Burke, Heather, et al. ‘Nervous Nation: Fear, Conflict and Narratives of Fortified Domestic Architecture on the Queensland Frontier,’ Indigenous History, no. 44, 2020, pp. 21-57, https://search.informit.org/doi/10.3316/informit.796988097787779.

Cahir, Fred, Dan Tout, and Lucinda Horrocks. ‘Reconsidering the Origins of the Australian Legend,’ Agora, vol. 52, no. 3, 2017, pp. 4-12, https://search.informit.org/doi/10.3316/informit.069512373799807.

Price, Richard N. ‘The Psychology of Colonial Violence.’ In Violence, Colonialism and Empire in the Modern World, edited by Philip Dwyer and Amanda Nettelbeck, Springer, 2018, pp. 25-52, https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-319-62923-0_2.

Ryan, Lyndall, et al. Frontiers Massacre Map Stage 4, University of Newcastle, Australia, 2022, https://c21ch.newcastle.edu.au/colonialmassacres/detail.php?r=658.

Stirling, A. W. The Never Never Land: A Ride in North Queensland, Sampson Low, Marston, Searle & Rivington, 1884, https://search.library.uq.edu.au/permalink/f/18av8c1/61UQ_eSpace193891

Comments

Your email address will not be published.

We welcome relevant, respectful comments.