History and Fiction: Mapping Frontier Violence in Colonial Queensland Writing

By Anna Johnston, 2022 John Oxley Library Honorary Fellow. | 2 June 2023

Guest blogger: Professor Anna Johnston - 2022 John Oxley Library Honorary Fellow

Users are advised that this article contains Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander material that may be culturally sensitive where annotations and terminology have been used from an era at time of creation and may be considered inappropriate today. Material may also contain images, voices or names of deceased persons.

Queensland’s history since 1859 has provided writers and illustrators with many opportunities to engage the public imagination. Tales of adventure, new opportunities for settler pastoralists and migrants, and depictions of Queensland’s beautiful and challenging environments—from deserts to shipwrecks—filled colonial newspaper columns. These were “the strange romances which write themselves, often in letters of blood, amid the half-unknown, mysterious regions of tropical Australia”, the writer Rolf Boldrewood declared. As one of the British Empire’s new colonies in the latter part of the nineteenth century, Queensland drew international attention: “As Queensland has been set the latest, so she is by far the brightest, jewel in Queen Victoria’s Crown”, the Queensland Magazine boasted.

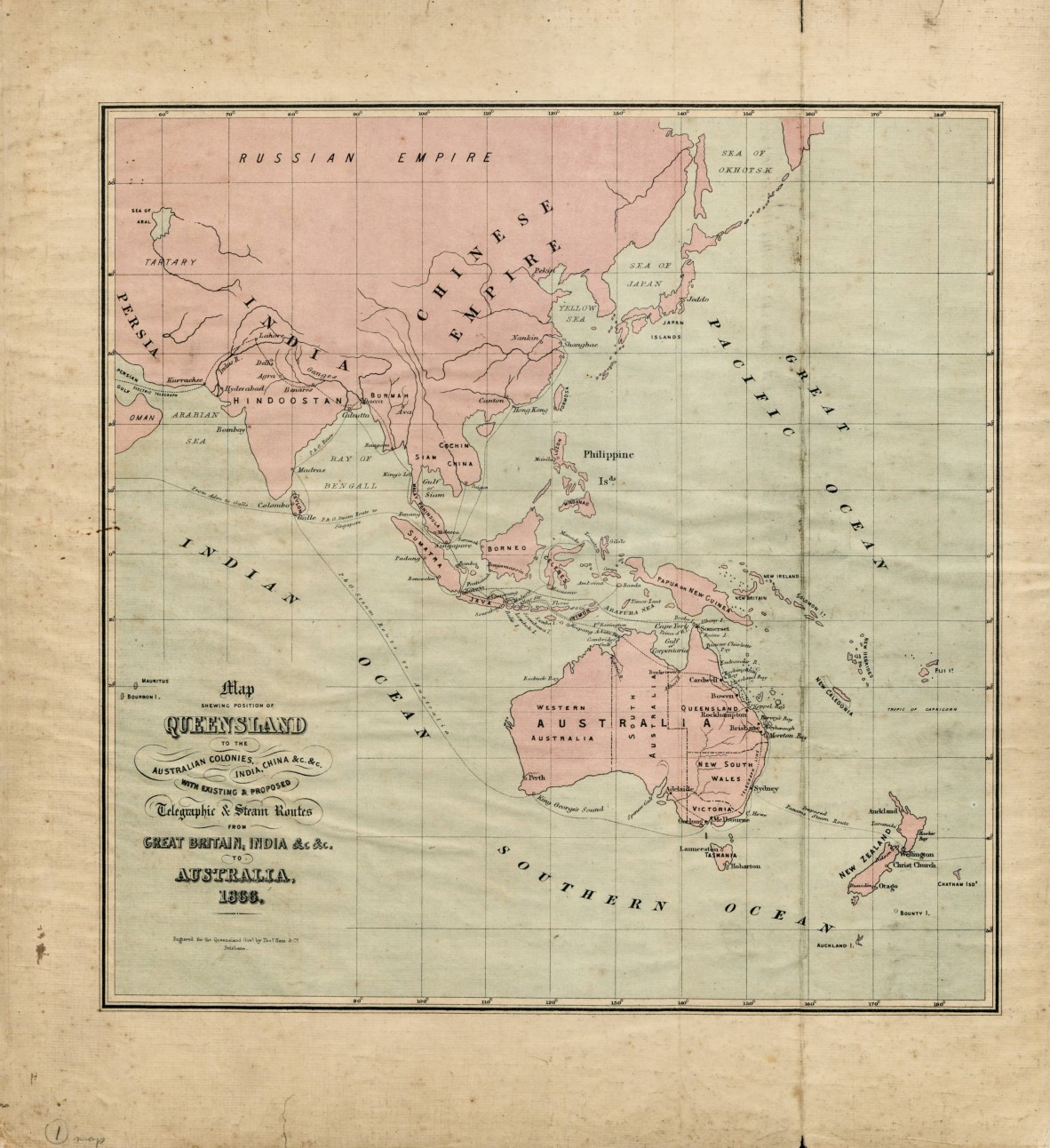

Map showing the position of Queensland to the Australian colonies, India, China & C. & C. with existing and proposed telegraph and steam routes from Great Britain, India & C. & C. to Australia 1866.

Atlas of the colony of Queensland, Australia compiled at the office of the Surveyor-General. 1865, Brisbane, Government Printing Office, pg 7. John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland.

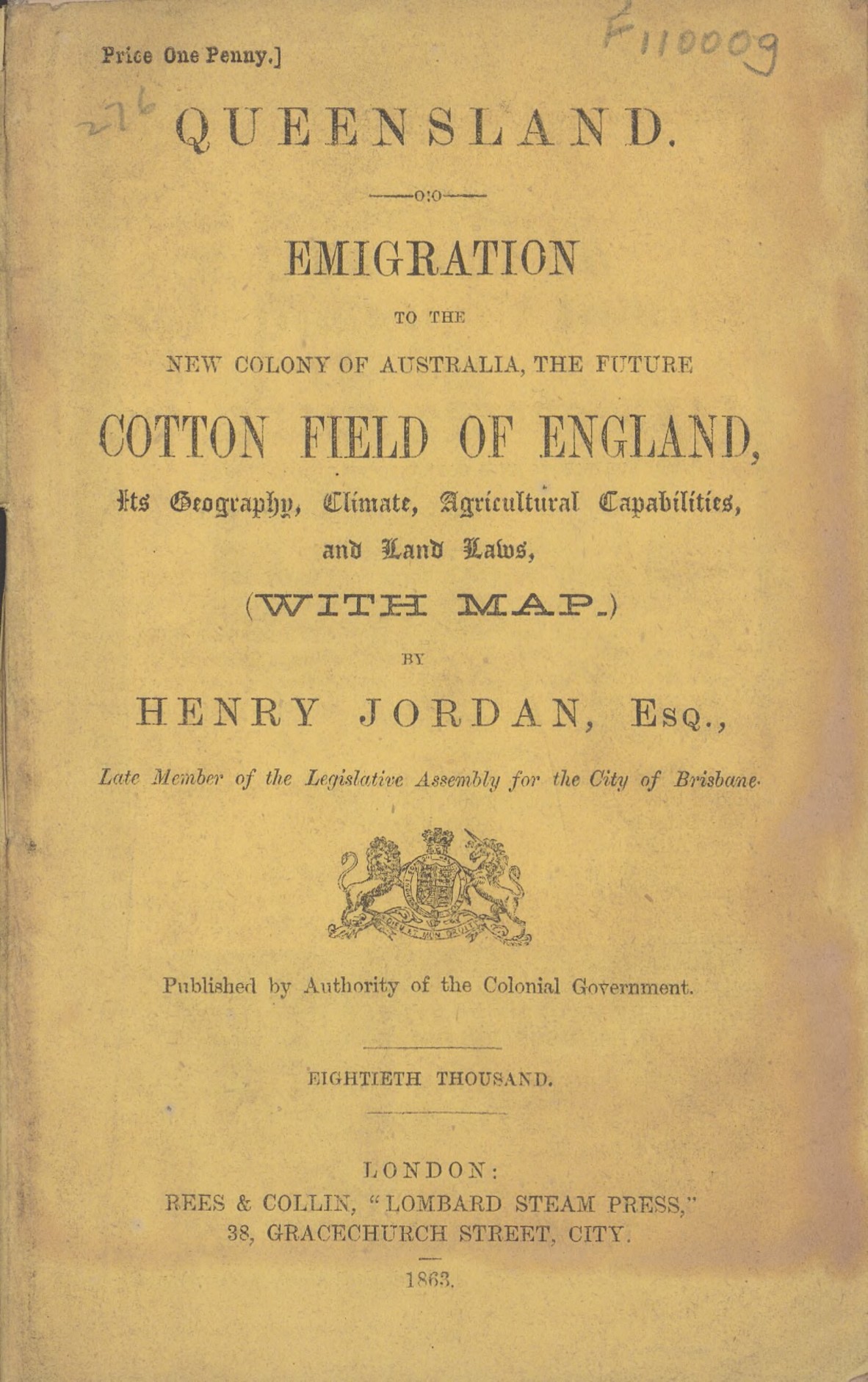

Queensland: emigration to the new colony of Australia, the future cotton field of England: its geography, climate, agricultural capabilities, and land laws (with map), Henry Jordan, 1886, London: Rees & Collin, Lombard Steam Press. National Library of Australia, Trove.

Australian writers such as Ernest Favenc wrote stories about Queensland for the press, as did those who moved between England and Australia, such as Francis Adams and Hume Nisbet. Some wrote stories under the protection of a pseudonym—a common practice in nineteenth-century journalism which was particularly useful when the content was controversial.

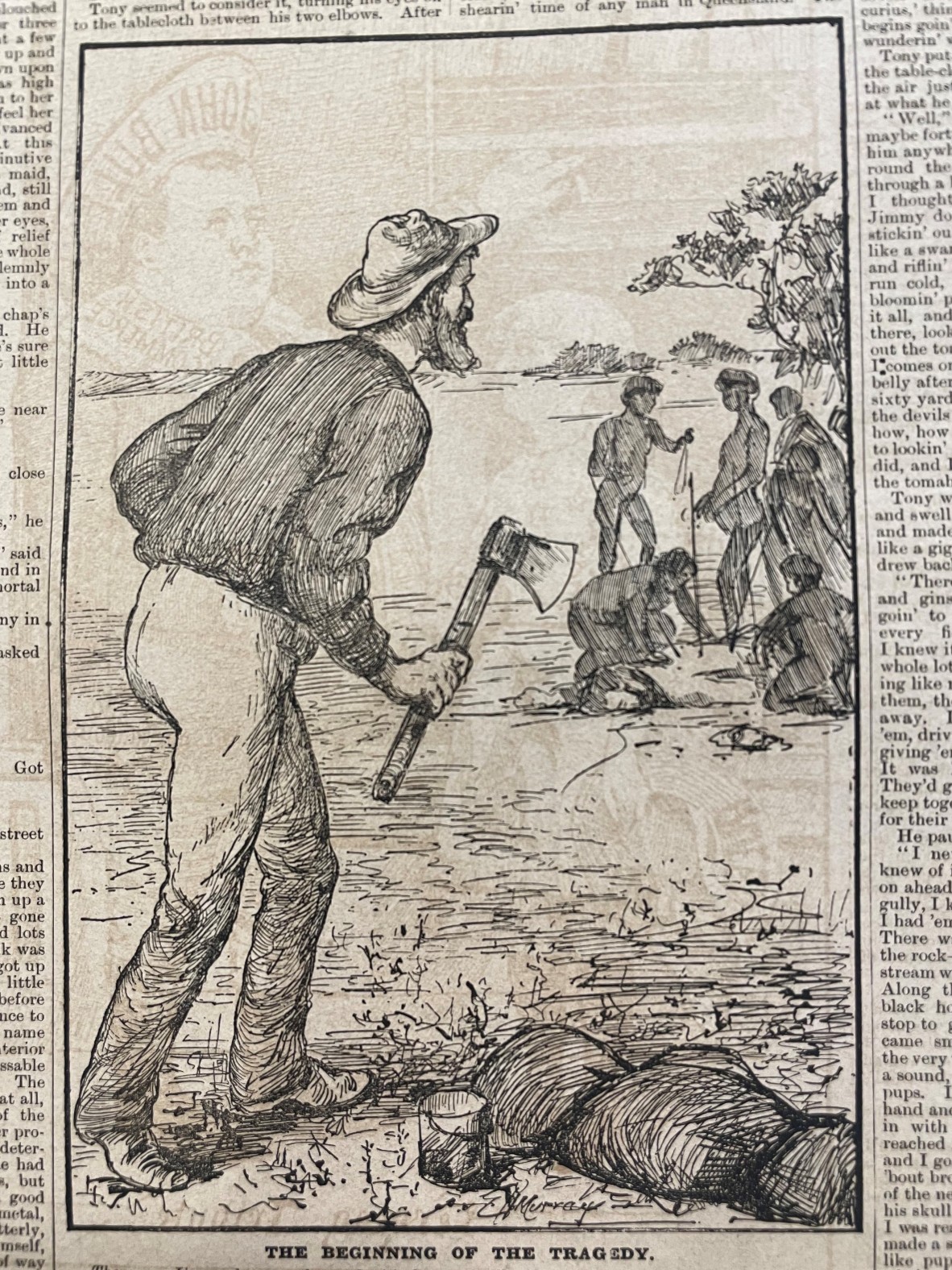

The Boomerang 1888 illustration, Francis Adams, Milson's Point, N.S.W. : W. & F. Pascoe. John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland.

As the John Oxley Library Honorary Fellow for 2022, I am researching colonial fiction published in newspapers and magazines to map how stories (and some poems) represented frontier wars and colonial violence in Queensland.

These stories were often well-written and pacy, attracting many readers. They often used the style of adventure fiction that followed the global expansion of the British Empire. Adventure fiction was hugely popular during the Victorian period and beyond: every night, Britons read themselves to sleep with these kinds of stories, literary historians suggest. Today we may find them dated, with views that may now seem offensive, but they were hugely influenced in shaping public knowledge.

Australian writers used their own “adventures” as well as accounts by others to create accessible stories with local details for armchair readers. They often dealt in racial stereotypes, especially about First Nations peoples and cultures. Some authors revised stories that had first appeared in colonial newspapers for book publications that circulated widely in Britain and Australia.

These fictional accounts provoke many questions for me as a researcher. How was the violence that accompanied pastoral expansion depicted alongside rosier pictures of the new colony? How did fiction writers engage with the deaths and massacres caused by the Queensland Native Mounted Police?

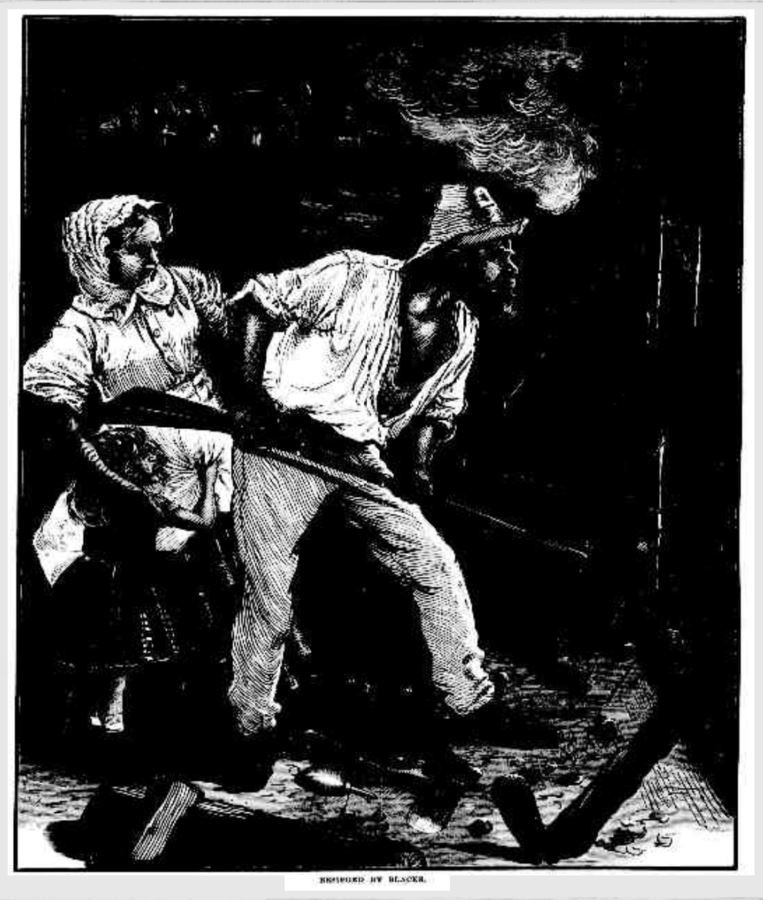

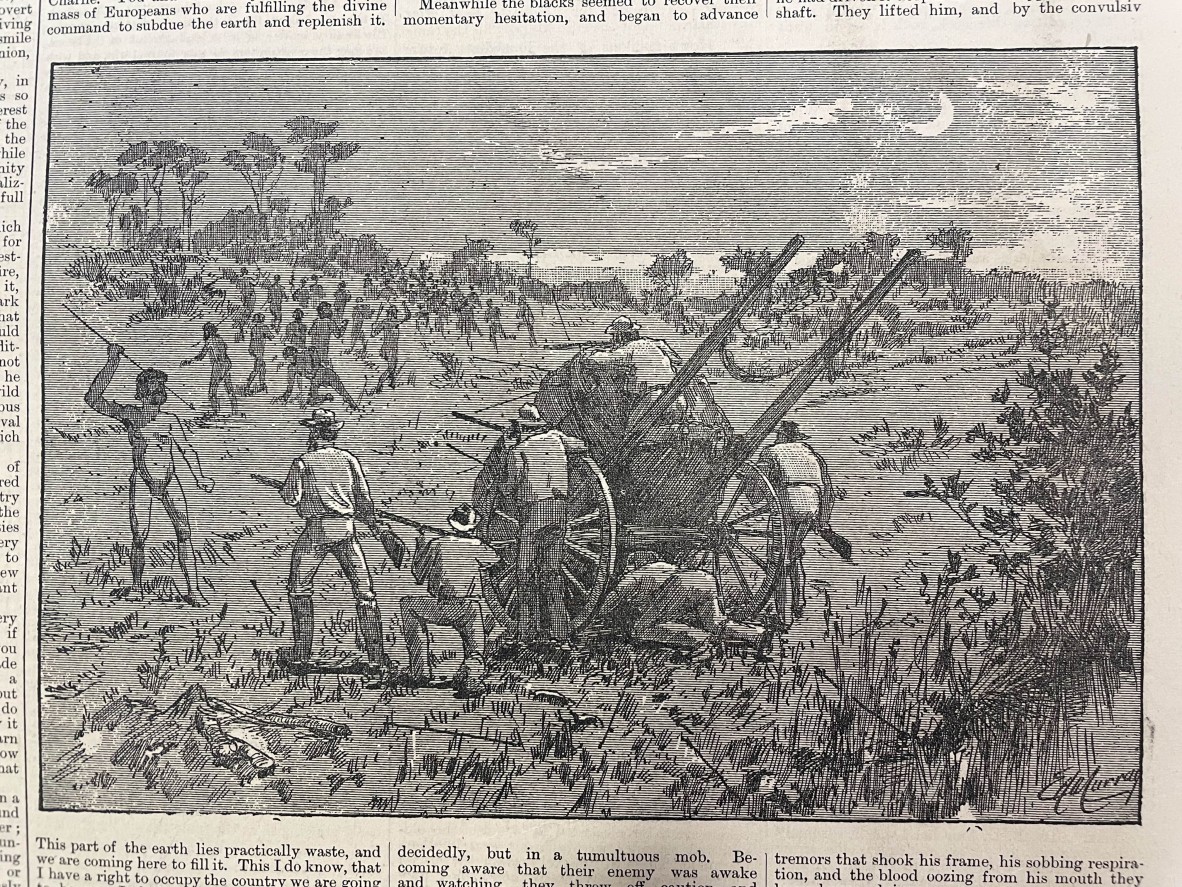

Besieged by blacks, The Australasian Sketcher with Pen and Pencil (Melbourne, Vic. : 1873 - 1889) 21 March 1874, pg 217. Trove, National Library of Australia.

Did writers simply reflect settlers’ concerns about the safety of their homes and families or did they try to imagine Indigenous peoples’ experiences and perspectives? Some like Carl Feilberg certainly tried to represent the distaste some settlers felt about colonial violence.

Attacked by Blacks, The Boomerang 1888, Carl Feilberg, Milson's Point, N.S.W. : W. & F. Pascoe. John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland.

His character Macallan, an experienced bushman, chides younger men for their propensity to violence: “No, I will not strike the first blow. God knows, we white men bring enough evil on the poor creatures—our presence here is a certain death-warrant to them—but I am not going to incur the blood-guiltiness of an unprovoked massacre”.

Did fiction sometimes provide a mask for writing about real historical events and / or their authors’ experiences? William Charles Wilkes' poem “The Raid of the Aborigines” (1845) predates Queensland’s separation from New South Wales but it is set in the Darling Downs. It was first published in the gossipy newspaper Bell's Life in Sydney, reprinted in the Moreton Bay Courier in 1854 (when Wilkes was its editor, 1848-1856), in the Queensland Magazine and other late-nineteenth-century publications in illustrated forms. The poem features the conflict known as “The Battle of One Tree Hill”, in which Indigenous people successfully defended their country. In this mock-heroic poem, settlers are made to look vain and foolish.

Old Bush Favourites, the raid, William Charles Wilkes, Queensland Figaro and Punch (Brisbane, Qld. : 1885 - 1889), 26 November 1887, pg 6. Trove, National Library of Australia.

Indigenous women flatter and distract them while Indigenous men entrap them using bush knowledge and defeat them by rolling boulders down the steep hill:

In short it was as plain as the nose on your face,

That the whites would be found to retreat in disgrace.

(Wilkes “The Raid of the Aborigines”, Part II)

Indigenous characters are also treated satirically in the poem, but are named as individuals rather than mere stereotypes:

Meantime with the others the battle raged high,

For Pittson already had got a black eye

From the fist of Young Moppy, and Campbell had flung

At the head of poor Wingate a huge bullock's tongue,

While one of the gins, with a kangaroo spear,

Had sadly annoyed Billy Ure in the rear[.]

(Wilkes “The Raid of the Aborigines”, Part II)

While some of the language is dated and offensive, we can glean important information from this poem and link it to historical sources. Recent local historical research with Indigenous communities reveals that the “Young Moppy” of this poem is more properly known as Multuggerah and his name is now commemorated in the region as well as the site at Meewah / One Tree Hill.

The most challenging question I want to ask is how we, as contemporary readers, can re-imagine our role as witnesses to this history? These are the complex histories of the country that both Indigenous and non-Indigenous Queenslanders now call home. Can we use literature to engage imaginatively with Queensland’s past as part of the truth-telling called for by the Uluru Statement from the Heart and the Queensland Government’s Pathway to Treaty?

I’m very much looking forward to what I will learn during my Fellowship, and welcome ideas from readers, researchers, and communities who share my interests in this fascinating literary archive of Queensland’s memory.

Professor Anna Johnston,

2022 John Oxley Library Honorary Fellow.

More blogs by Professor Anna Johnston:

Comments

Your email address will not be published.

We welcome relevant, respectful comments.