Good as Gold: Love stories in Australian frontier fiction

By Guest bloggers: 2022 John Oxley Library Honorary Fellow Professor Anna Johnston and UQ student Connor Crossley. | 15 February 2024

St. Valentine’s Day. Illustrated Australian News for Home Readers, 24 Feb. 1875, p. 17. John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland.

Guest bloggers: UQ student, Connor Crossley and 2022 John Oxley Library Honorary Fellow, Professor Anna Johnston.

In working with Professor Anna Johnston on her project History and Fiction: Mapping Frontier Violence in Colonial Queensland Writing, I was prepared to read a lot of, well, violence. And certainly I did – but the fiction was wide-ranging, and touched on themes outside of my understanding of settler colonialism. One theme I was surprised to find so frequently was that of love.

Love in frontier writing was both traditional and subversive, representing relationships between white settlers, as well as across racial boundaries – for example, the dastardly Frank Melvil (based on the real-life Frank Jardine, who married a Samoan woman) and Nini of the Sea Eel tribe in Francis Adams’ ‘The Red Snake.’ In particular, the gold rushes of northern Queensland provide a wonderful backdrop and motivation for the blooming and withering of love.

‘The Red Snake’ title image.Adams, Francis. "The Red Snake." The Boomerang, 1888, pp. 17-18, doi:10.1017/S1321816600004608.John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland.

The Australian gold rushes were an opportunity for new settlers in Australia to find home and prosperity, away from their birthplaces of the United Kingdom, China, or elsewhere. As Katrina Dernelley notes, these people ‘saw in the shimmering haze of gold fever the opportunity to dream of home, comfort and stability.’ While Dernelley does not focus on ‘a gold rush landscape populated by itinerant men,’ this is exactly what many of the stories in History and Fiction portray: men journeying away from their homes to find their fortunes and return rich, often spurred on by a sense of duty to or outright demands from their lovers. Typically, these stories end in tragedy – but what good love story doesn’t?

Three stories in particular follow this format closely: the anonymous Bushman’s ‘The Mysterious Mountain,’ Louis Becke’s ‘The Prospector,’ and Alita’s ‘How Graham Lost His Arm.’

The Mysterious Mountain

‘The Mysterious Mountain’ title image. Bushman. "The Mysterious Mountain." The Boomerang, no. 214, 1891, p. 10. John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland.

Two courters, Jack and Jennie, are promised to each other. They are young and beautiful, but, despite their love, cannot be engaged:

‘Oh, Jack! How can I?’

And the speaker, a winsome brown-haired, brown-eyed maiden of eighteen looked up appealingly at the stalwart young fellow who held her hands in his.

‘And why can’t you Jennie?’ replied Jack, somewhat sullenly, ‘you promised me long ago.’

Jennie recounts her family’s financial issues – her aunt and uncle are retired, impoverished, and indebted. Jennie feels a strong obligation to her aunt and uncle, ‘who took [her], an orphan child, helpless and alone, and who have cared for [her] and loved [her].’ Jack, spurred on by love and duty, promises to head to the gold fields and return solvent, ready to begin a new life betrothed:

‘I ask no woman to wed poverty with me,’ replied Jack proudly, ‘I have brought back little with me but fever from the North this time, but oh, Jennie, my love, promise me to wait for me for one year more, and if I do not come to claim you then, forget me, for you will never see me again.’

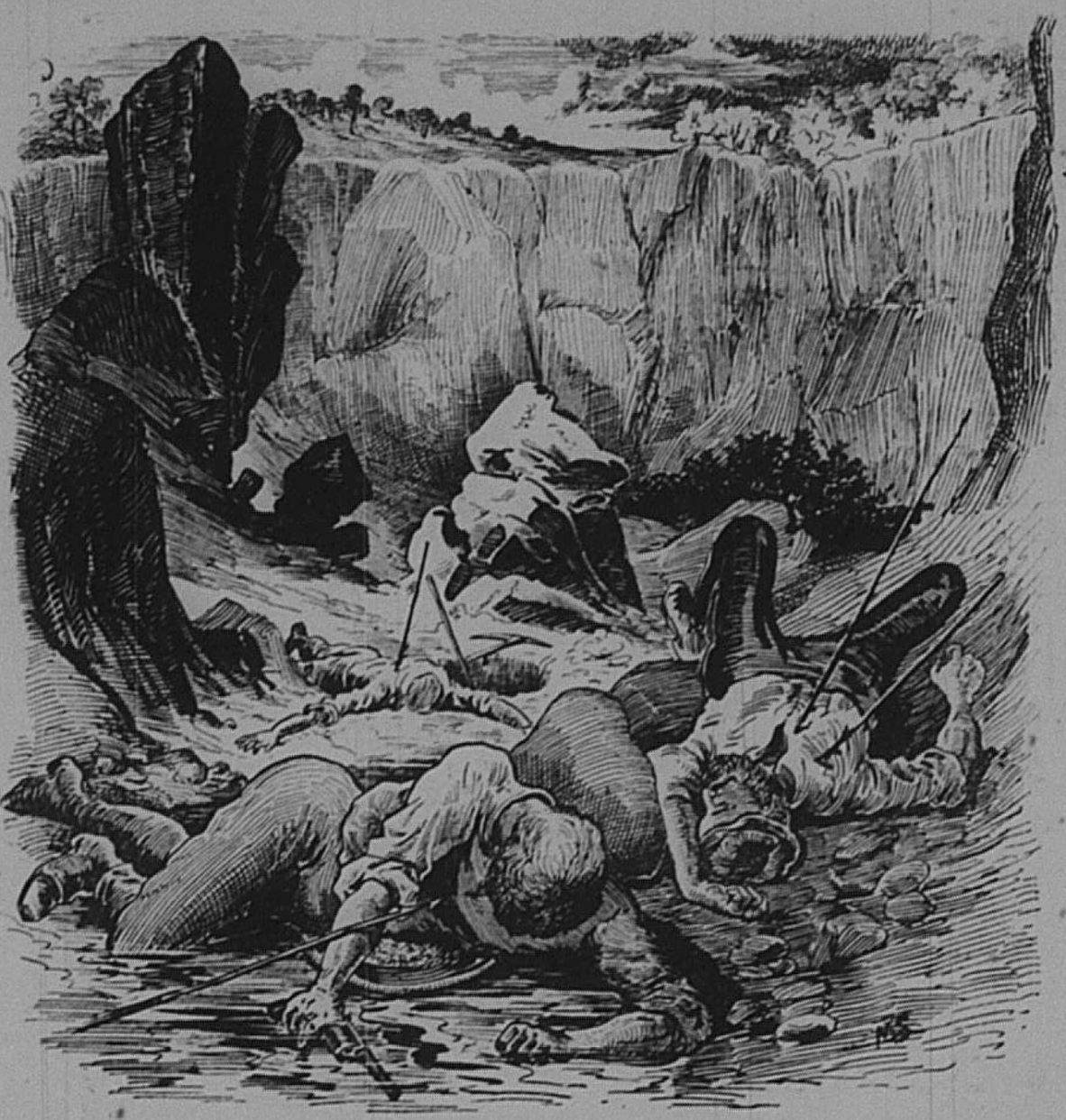

Jack leaves for the north to prospect for gold beneath a large granite mountain, which is likely Black Mountain in the Kalkajaka National Park, a place of cultural significance to the Eastern Kuku Yalanji people. Under attack by Eastern Kuku Yalanji warriors, Jack and his companions head further up the mountain, where it is said that Taupo blessed the people with safety from spears. Heedless of the protocols they are transgressing, the white men summit the mountain, find a creek, and immediately pan ‘a nugget, fifty ounces if it’s a pennyweight.’ But the men are doomed by their greed and ignorance: they are speared to death by warriors defending the site.

Jennie is left lonesome. ‘After years of weary waiting for the lover who never came,’ Jennie marries and becomes a mother. However, her love for Jack never fades:

Yet at times, a wistful look comes into those gentle eyes and while her little ones play round her knee she thinks of the brave young lover who went forth for her sake into the deadly North and whose fate she will never know.

Prospectors dead atop the Mysterious Mountain. Bushman. ʻThe Mysterious Mountain.’ The Boomerang, no. 214, 1891, p. 10. John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland.

The Prospector

Louis Becke’s hero Sam Chambers recalls reading ‘a most interesting and romantic story of the Canadian North-west,’ in which a trapper discovers that he is stationed near a father and daughter. Struggling through a ‘bitter winter,’ the family fail to trap anything substantial. To ease their struggles, the lonesome hunter secretly places some of his game in their traps – and, during a particularly frightening blizzard, saves them from their hut ‘at the risk of his life.’ This story relates directly to Chambers’ romance with his wife, Aline: she exclaims, ‘Sam, is not the story very much like ours, except that the Canadian girl was single and I was married?’

As the story goes, Chambers had been the ‘leader of a prospecting party in the Gulf country, on the eastern watershed’ – that is, Kunjen Country. He was joined by three others, including his friend Combo, a Bindal man from ‘Cape Bowling Green… in the Cleveland Bay district.’ Attacked by Kunjen warriors, Chambers and Combo flee to the Coen River, where they come across an old white man by his cutter, whose crew from ‘the Cape Grafton tribe,’ or Gunggay Country, had mutinied. Together, the three men sail to Sydney.

In Sydney, Chambers arranges prospecting equipment to be sent to the gold field along the Coen River. Combo and Chambers return, and for many months fare well, prospecting under good weather; however, Combo goes missing en route to a nearby cattle station. Chambers finds him the next day, injured and reclining on a boulder. He had been shot by a man as Combo passed by his hut, twenty miles away.

Combo and Chambers go to find the man, only to realise he lives with his wife, Aline. While the husband is away, Aline tells Chambers and Combo of their struggles, saying that ‘During this last week [they] have only washed out two ounces’ of gold. Aline bursts into tears, telling them that her husband is ‘a dangerous man,’ an alcoholic who squanders whatever meagre savings they have. Chambers begs her to leave her husband, but Aline, stalwart and feeling a sense of obligation to family, refuses, saying that she ‘must bear [her] fate.’

Chambers forms a plan. He tells Aline to hide half of their findings and points her to a field which he claims is replete with gold. Chambers then secretly hides some of his own gold in the field, allowing Aline to squirrel away ‘eight ounces out of the fourteen ounces [they] got altogether.’ When Chambers and Combo visit again, Aline’s enraged husband catches them by surprise, and Aline saves Chambers’ life:

Suddenly she uttered a shriek, sprang at me, and gave me a violent push with both hands. A second later came the report of a gun, and I went down with a bullet in my right side, and at the same time Combo fired, and then giving a loud yell of triumph dashed across the creek, and a minute or two later I heard a second shot. Taking off my shirt, [Aline] looked at my wound.

While Aline tends to Chambers’ wounds, Combo approaches the alcoholic husband and ‘fix[es] him up all right.’ Aline alternates between joy and despair, feeling a newfound sense of freedom while grieving her late husband. In the morning, ‘moved by some sudden impulse, born of years of agony, mental and perhaps physical, [she] took up a miner’s pick and smashed [the hut] oven to pieces,’ symbolically freeing herself from the shackles of a loveless marriage.

Chambers, Combo, and Aline travel to a nearby station, where Aline is left ‘in the care of the wife of the manager of the cattle station, where she remained a year.’ Chambers finishes up his work at the gold field, he and Aline fall in love, and Aline ‘promise[s] herself to [Chambers].’ The two travel back to Brisbane, where they are married.

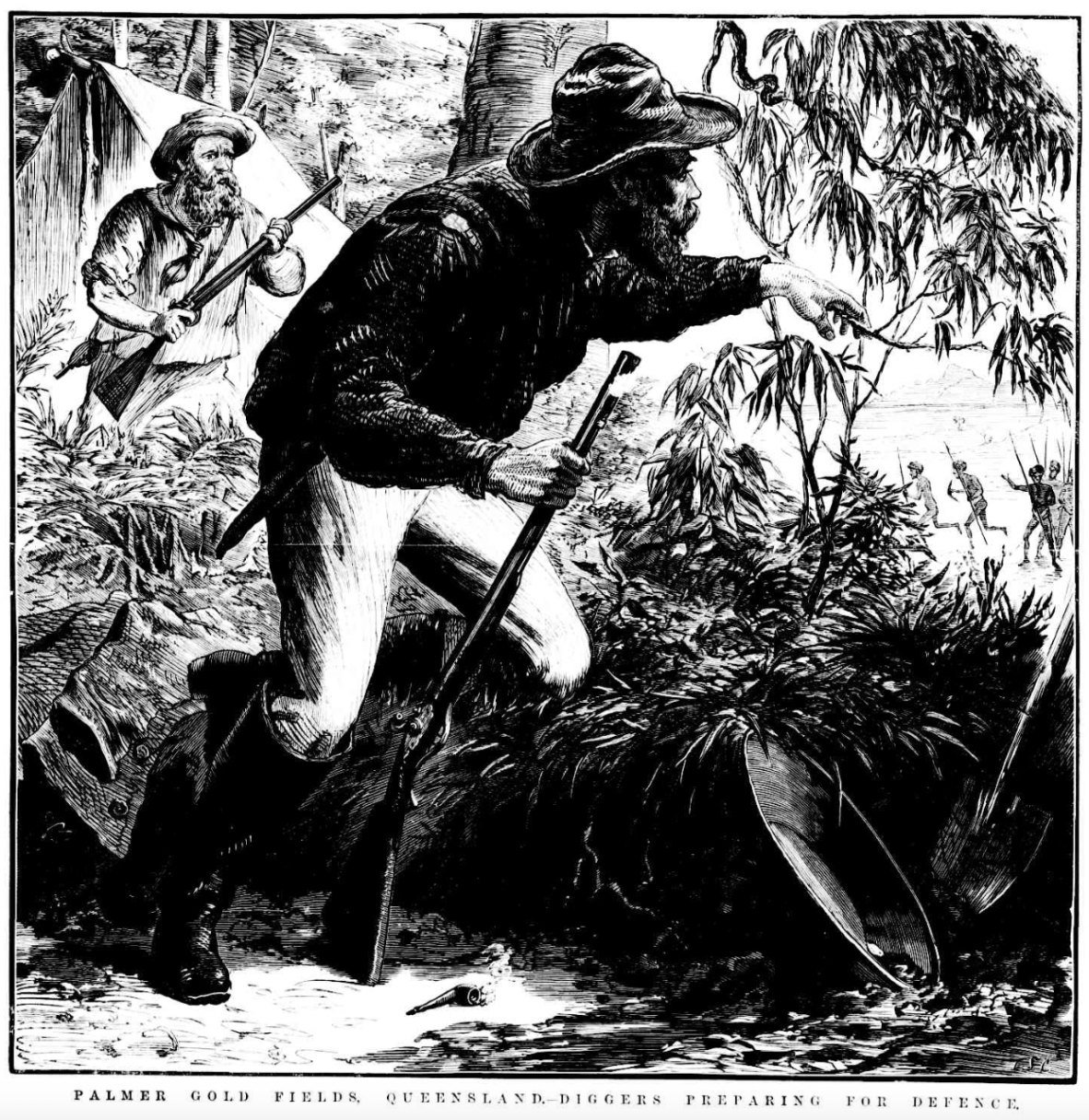

Palmer Gold Field, Queensland. Diggers Preparing for Defence. “The Dangers of the Palmer – A Native Attack.” Illustrated Sydney News and New South Wales Agriculturalist and Grazier, 22 Jul. 1876, p. 14. Trove, National Library of Australia.

How Graham Lost His Arm

Reclining under a gumtree in the ‘Wild River district’ of Far North Queensland, Graham, a ‘tall, broad-shouldered, good-looking fellow’ tells the tale of how he lost his arm. As a young man, he was eager to make his fortune in the gold rushes, so that he could return monied and marry his sweetheart, Jennie (clearly a popular name for colonial heroines):

She was a jolly, nice-looking girl; and, by jove, her figure was A1, I can tell you. Of course we were going to love each other all the days of our lives, and were going to live in a little heaven all our own. I suppose it was the fact of this heaven being such a mighty long way in the distance which made me unusually anxious to bring it nearer by packing off to the diggings, and jumping into a fortune all at once, as I had heard others were doing.

Jennie, equally eager to begin her life with Graham, ‘urged upon [him] the advantages [he] might gain by going.’ Indeed, Graham’s father sells his shop and the two men journey from their home in Maryborough to ‘the Etheridge,’ which spans predominantly across Agwamin Country.

After an arduous journey to the Etheridge, they set up camp. Graham and his father, along with multiple other prospectors, fail to find anything of value – in fact, ‘where one made a pile, twenty lost even what little they had brought with them.’ In the face of this hardship, Graham’s father ‘got laid up with fever,’ growing more unwell day by day. Graham decides that he must risk heading to town for provisions, and ‘reloaded a pair of revolvers and placed them at his [father’s] side’ for safety against possible attacks.

“The Etheridge.” The Queenslander, 29 Jul 1876, p. 28. Trove - National Library of Australia.

Graham’s worst fears are realised – upon returning, he finds that his father was brutally murdered. Graham flees from the tent to find help, but the Agwamin warriors are still nearby; a fight ensues, Graham’s arm is smashed, and he is knocked unconscious by a ‘nullah nullah.’ His fellow miners manage to rout the attackers, saving Graham’s life – but, regardless, his arm has to be amputated.

After recovering, Graham returns home, ‘and landed in Maryborough a poorer man by far than when [he] left.’ His sisters are pleased to see him – but, regrettably, Graham’s love had abandoned him for a man that Graham, perhaps due to his heartbreak, sees as inferior:

The girls were glad to see [him] again, and as for “Jennie” ([his] sweetheart), well, she simply gave [him] the go-by, and in less than six months she married a foppish bit of a counter-jumper with about six hairs on his upper lip, and about as many coppers in his pockets.

In many stories from the Australian frontier, establishing home and family is of utmost importance. While some stories feature male characters who are already engaged or married, many depict how lonely settlers might find love in a new, unknown land. Bushman’s ‘The Mysterious Mountain,’ Louis Becke’s ‘The Prospector,’ and Alita’s ‘How Graham Lost His Arm’ tell deeply tragic stories, pairing extreme hardship alongside potentially lifelong love. Perhaps, in the end, the two together make love all the sweeter.

Blog written by UQ student Connor Crossley and 2022 John Oxley Library Honorary Fellow, Professor Anna Johnston.

See the Queensland Memory Awards website for more information on State Library's fellowship and awards program.

More blogs by Professor Anna Johnston:

-

History and Fiction: Mapping Frontier Violence in Colonial Queensland Writing

-

Fear on the Frontier: Settler Anxieties in Queensland Frontier Fiction

-

‘The Selvage Edge of Civilization’: Queensland Fiction and Colonial Histories

Read more love stories from State Library's collection:

Comments

Your email address will not be published.

We welcome relevant, respectful comments.