2024 Digital Collections Catalyst & guest blogger: Evelyn Saunders

Min(d)ing the Dead, my interactive project for the State Library of Queensland’s 2024 Queensland Memory Awards Digital Collections Catalyst [1], grew out of a fascination with the town of Ravenswood that began in 2013 whilst organising filming for “Breaker Morant the Retrial”[2], a Film Projects-led dramatised documentary for the History Channel.

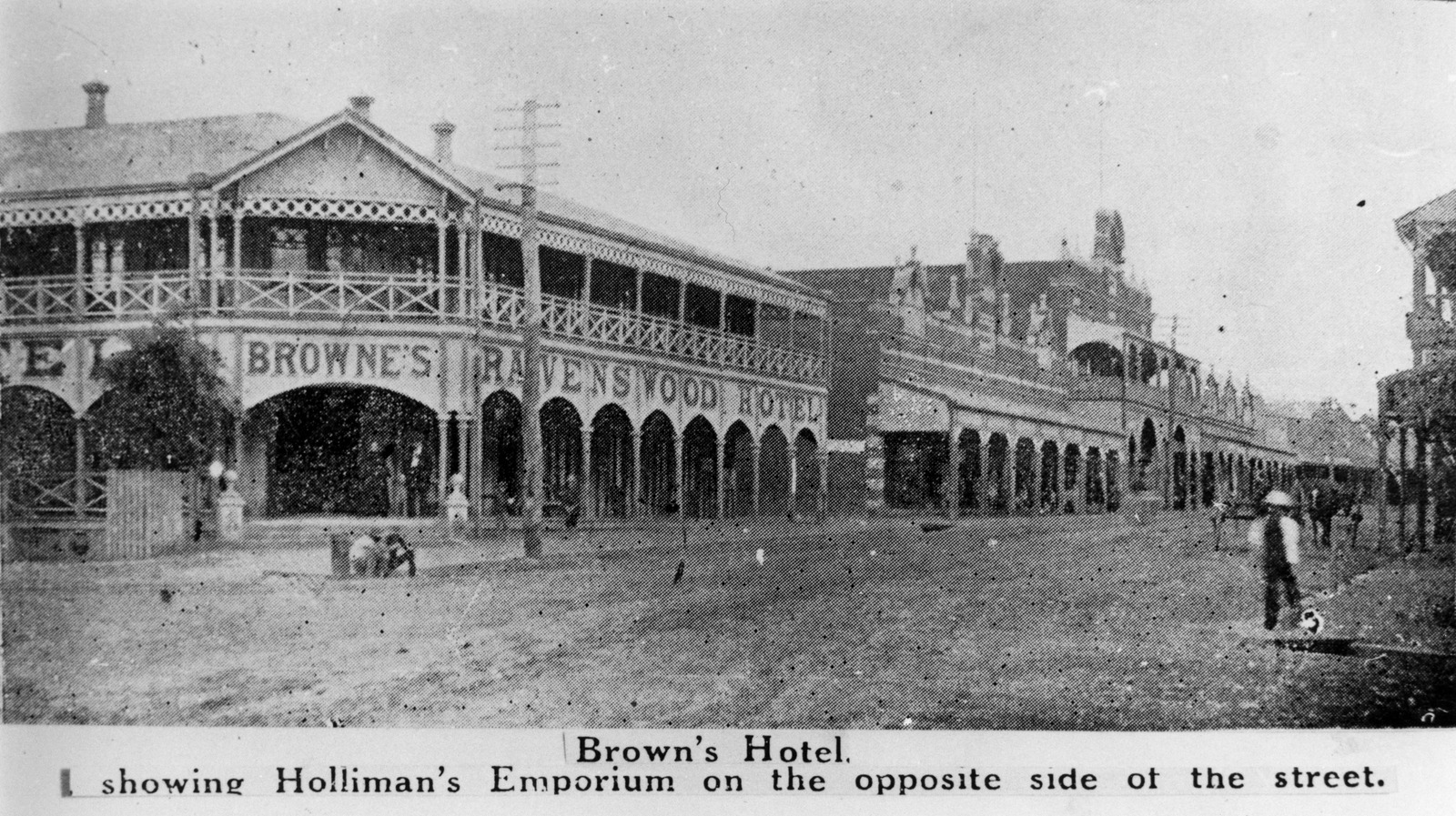

Browne's Hotel on Macrossan Street, facing south-east, Ravenswood. Ravenswood, Queensland’s first large inland settlement and North Queensland’s first major mining town.

John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland. Negative number: 164742

Driving into Ravenswood on a weekday in February 2013, the town’s isolation struck me, its obvious history (abandoned rusted machinery, ruins, chimneys, metal silhouettes of goats and miners, old buildings fitted out with late 1800s furniture, information boards…), and the fact that it had numerous heritage buildings dated between 1873 and 1903 inside a three-hundred-metre-long ‘main drag’.

Macrossan Street facing south-east, Ravenswood, circa 1980. Image courtesy of National Trust of Australia (Queensland).

Reverse view of Macrossan Street facing north-west circa 1980. Image courtesy of National Trust of Australia (Queensland).

Were it not for the shopkeeper at the Post Office, and a few bar staff and fluoro-clad drinkers at the Railway and Imperial Hotels, I’d have thought Ravenswood was a well-preserved ghost town. As it was, the (approximately) one hundred and fifty permanent residents and the drive-in drive-out mine workforce were either at work, escaping the heat at home, or attending school. Tourist season, when grey nomads and other motorised adventurers descend to check out the heritage buildings[3], old-world mine sites, and the museum, wouldn’t start until winter. Ravenswood was a film-making heaven, a perfect location and, happily, the Ravenswood Restoration and Preservation Association, Charters Towers Regional Council, Resolute Mining, managers of the Ravenswood Community Church, local business owners, and community members came on board to help us recreate the late eighteen and early nineteen-hundreds for our show. The locations included the Railway Hotel[4], the Imperial Hotel[5], Butler’s Cottage[6], St Patrick’s Catholic Church[7], and the cells at the Ravenswood Court House Museum[8].

Eight years later, during COVID-19, I was on a location recce with a screenwriter and was puzzled to see upon entering the town that a thirty-metre-high wall of earth had risen some two hundred metres behind the main heritage area.

Ravenswood Ambulance Station[9].

Photographer: Evelyn Saunders

Having grown up in a mining town and with relatives in the industry, I’m aware that bund walls operate to buffer townships from mining activities. However, this one was positioned between the town and its cemetery. It’s frivolous I know, but suddenly I felt nostalgic. In 2013, I’d been sitting at the curved bar of the Imperial Hotel chatting to the publican at the time, John Schluter, about ghosts. It was a conversation I’d been having with a few people in the region, and I’d been struck by the everyday nature of their stories and how they ranged from ghost dogs to ghost people, to ghostly noises. John quietly mentioned that from time to time, usually late at night when he was packing up, a presence would walk through the door and sit at the end of the bar. I can’t remember whether the story was that the ghost had ventured down the hill from the cemetery but, in my imagination, he had. Whether the silent barfly now treks through a mine and up and over the bund wall may well remain a mystery. Sadly, John Schluter, the story’s source, passed away in 2020[10].

As you may gather, I have an active imagination. It’s helpful in my job as a researcher and writer because it fuels questions. I’m also something of a cemetery buff. I find their environments fascinating, and the dates and information on headstones reveal a lot about a town’s history and a population’s culture – which is also why they have heritage value[11].

May Crow’s 1997 biography “Ravenswood Remembered”[12] is particularly interesting in this respect:

The cemetery was always a place of interest for me when I was little. My mother would go over the hill to the cemetery most Sunday afternoons, and some other ladies would be there, and they would have a great gossip. There was a shed there with seats where they could sit in the shade.

In 2021, walking to the cemetery was no longer so simple. My writer friend and I were told to go back out of town and then turn left at Burdekin Dam Rd to get to the other side of the bund wall. It was here that we found the cemetery of May Crow’s youth, separated from the town by an uptick in the mine’s activities. The cemetery was still a strangely romantic array of gravestones and rusted iron surrounds. The landscape around it, however, was no longer a vast, relatively flat space. Ravenswood Cemetery now stood inside a mining pit.

You can probably guess this is when I first muttered “min(d)ing the dead”, an ironic observation about the cemetery being a sacrosanct island. However, as I began researching and reflecting upon the history of the changed Ravenswood landscape – the sale of the mine[14], the proposed expansion[15], the archaeologists and historians brought in to locate the first cemetery at Buchanan’s Gully, the exhumation of the remains[16], the relocation of the Ravenswood State School and its heritage buildings[17], the creation of a bund wall[18], the notion of a heritage town existing within a few hundred metres of a major mining operation[19] – the phrase “minding the dead” began to reflect the complexity of the Ravenswood situation. I wanted to better understand the relationship between mines and their towns. Not every town has a mine and these days not every mine has a town… but what happens when a heritage mining town, a tourist destination known for its heritage building and mine sites, suddenly finds its modern mining operations expand in a way that has the potential to put this heritage at risk? How do you work the balance sheet when it comes to being mindful of heritage and supporting the people who mind the heritage, and weighing it against the economic impetus of mining gold?

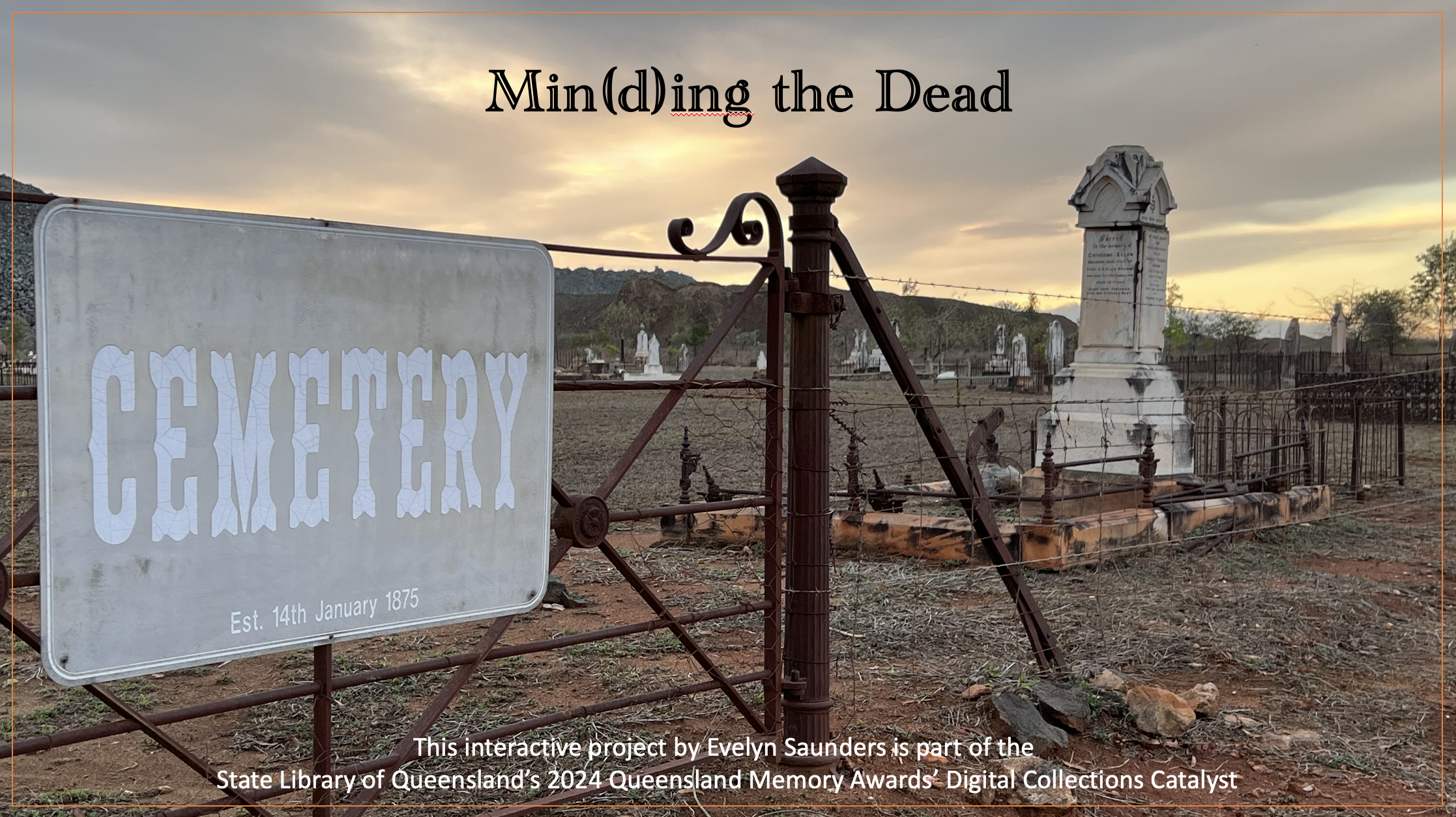

It was from these thoughts that my interactive project “Min(d)ing the Dead” was born. The materials that document the history of Queensland’s first large inland settlement[20] and North Queensland’s first major mining town[21] need to be unearthed and collated for posterity.

This blog series will document my journey towards delivering an interactive digital narrative (IDN) about heritage, identity, landscape, and commerce.

Ravenswood Cemetery.

Photographer: Evelyn Saunders

Other Blogs:

References:

[1] https://www.slq.qld.gov.au/digitalcatalyst

[2] https://www.facebook.com/profile.php?id=100039872296794 (photographs from Ravenswood shoot posted 22 April, 2013)

[3] https://apps.des.qld.gov.au/heritage-register/results/?q=Ravenswood (accessed 2/5/24)

[4] https://apps.des.qld.gov.au/heritage-register/detail/?id=600443 (accessed 2/5/24)

[5] https://apps.des.qld.gov.au/heritage-register/detail/?id=600446 (accessed 2/5/24)

[6] https://www.visitcharterstowers.com.au/butlers-cottage (accessed 2/5/24)

[7] https://apps.des.qld.gov.au/heritage-register/detail/?id=601829 (accessed 2/5/24)

[8] https://apps.des.qld.gov.au/heritage-register/detail/?id=601204 (accessed 2/5/24)

[9] https://apps.des.qld.gov.au/heritage-register/detail/?id=600445 (accessed 2/5/24)

[10] https://www.mytributes.com.au/notice/funeral-notices/philip-john-schulter/5353561/ (accessed 2/5/24)

[11] https://www.nationaltrust.org.au/services/cemetery-conservation/ (accessed 12/4/24)

[12] https://ones‑‑earch.slq.qld.gov.au/permalink/61SLQ_INST/tqqf2h/alma997415084702061 Mary Crow was born in Ravenswood in 1915. “Ravenswood Remembered”, Ravenswood Restoration & Preservation Association, 1997. ISBN: 0646319027.

[13] https://earth.google.com/web/@-20.11097836,146.88762262,267.34493678a,705.02298518d,35y,0h,0t,0r/data=OgMKATA (accessed 12/4/24)

[14] https://www.ravenswoodgold.com/ (accessed 12/4/24)

[15] https://www.abc.net.au/news/2020-11-17/ravenswood-gold-mine-could-become-queensland-super-pit/12887580 (accessed 12/4/24)

[16] https://www.abc.net.au/news/2018-07-06/ravenswood-lost-cemetery-bodies-reintered/9895768 (accessed 12/4/24)

[17] https://www.abc.net.au/news/2019-11-01/ravenswood-historical-school-moving-for-gold-mine/11649296 (accessed 12/4/24)

[18] https://planning.statedevelopment.qld.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0024/77820/RPI22-027-ravenswood-gold.pdf (accessed 12/4/24)

[19] https://www.statedevelopment.qld.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0024/48075/TIB-081220-Dave-Mackay-Ravenswood-Gold.pdf (accessed 12/4/24)

[20] https://apps.des.qld.gov.au/heritage-register/detail/?id=650038 (accessed 12/4/24)

[21] https://libserver.jcu.edu.au/specials/Archives/ravenshistoric.html (accessed 12/4/24)

Evelyn Saunders' Research Reveals talk.

Comments

Your email address will not be published.

We welcome relevant, respectful comments.