Loneliness

By Greer Townshend Guest blogger - 2022 Mittelheuser Scholar in Residence | 20 May 2024

Guest blogger: Greer Townshend - 2022 Mittelheuser Scholar in Residence

In me there is a vast and lonely place, where none, not even you, have walked in sight. A wide, still vale of solitude and light.

begins Love Sonnet XLIX by Brisbane-born poet Zora Cross (1890-1964).[1] Coveted by homesick First World War soldiers and their bereft lovers alike, Cross’s emotion-laden book Songs of Love and Life, published in 1917, was a sell-out.[2]

View of Barron Gorge during the construction of the Cairns Range Railway. John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland. Negative number: 69640.

Lauded for depicting emotion as a multifaceted ‘living thing’, [3] Cross’s poetry became best-known for unflinching portrayals of erotic love. Yet the work also speaks to the inverse of togetherness – loneliness. Love Sonnet XLIX posits that in essence we are all alone, and concludes by underscoring the hidden beauty of solitude:

And when from there I come to you, love-swift,

My mouth hot-edged with kisses fresh as wine,

Often I find your longings all asleep

And unresponsive from my grasp you drift.

Ah, Love, you, too, seek solitude like mine,

And soul from soul the secret seems to keep.

View of a drawing created by Kath Shillam in 1989. The artist's medium was ink and the drawing is a nude study of a man and a woman. Acc 6015, Len and Kath Shillam Papers, Australian Library of Art, State Library of Queensland. Image number: 6015-0009-0001

Loneliness as a negative emotion didn’t exist before 1800 and is closely linked to modernity and the rise of the individual, according to historian Fay Bound Alberti, author of A Biography of Loneliness (2019). [4] Alberti suggests gender, ethnicity, religion, and socioeconomic status all contribute to how we experience the emotion, and that we fear loneliness because of how we frame it. [5]

Front view of a Boy and Cat sculpture created by Kath Shillam in 1964. Acc 6015, Len and Kath Shillam Papers, Australian Library of Art, State Library of Queensland. Image number: 6015-0009-0001

Early 19th century Romanticists would have applauded Zora Cross’s reverence for seclusion. While viewed as problematic today, until around 1850 loneliness or ‘oneliness’ was considered ‘crucial to spiritual discovery’, allowing for communication with nature and with God.[6]

Interior view of a church on Peel Island, looking toward the altar. Acc 27550, Dr. Mogan Gabriel Collection, John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland. Image number: 27550-0014-0110.

Yet communication with an ever-present God was not an antidote to loneliness for Fanny Trundle, a pious British woman who migrated to Queensland with her husband and thirteen children in 1849. Despite having a large family, a happy marriage, many friends and a zealous commitment to God, Trundle’s sumptuous ink-filled diary, spanning over a decade, records persistent feelings of loneliness and anxiety.

Stained-glass window at St Paul's Church, Roma, 2018. Tegan Nielsen and Helen Bougoure, 2018, Acc 33286, Queensland Small Towns Documentary Project 2018: Roma, John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland. Image number: 33286-0023-0006

Trundle’s experience of loneliness was later exacerbated by an empty nest, widowhood and an increasingly complex relationship with God. ‘Being alone so much is not good for me,’ Trundle writes as she ruminated over her troubled adult son, ‘I hope God takes interest in my affairs. I crave sympathy but alas! The world has little for me.’[7] She later continues: ‘How lonely and how little understood even by the dearest. I wish I could feel greater trust in God in seasons of severe mental suffering.’ [8]

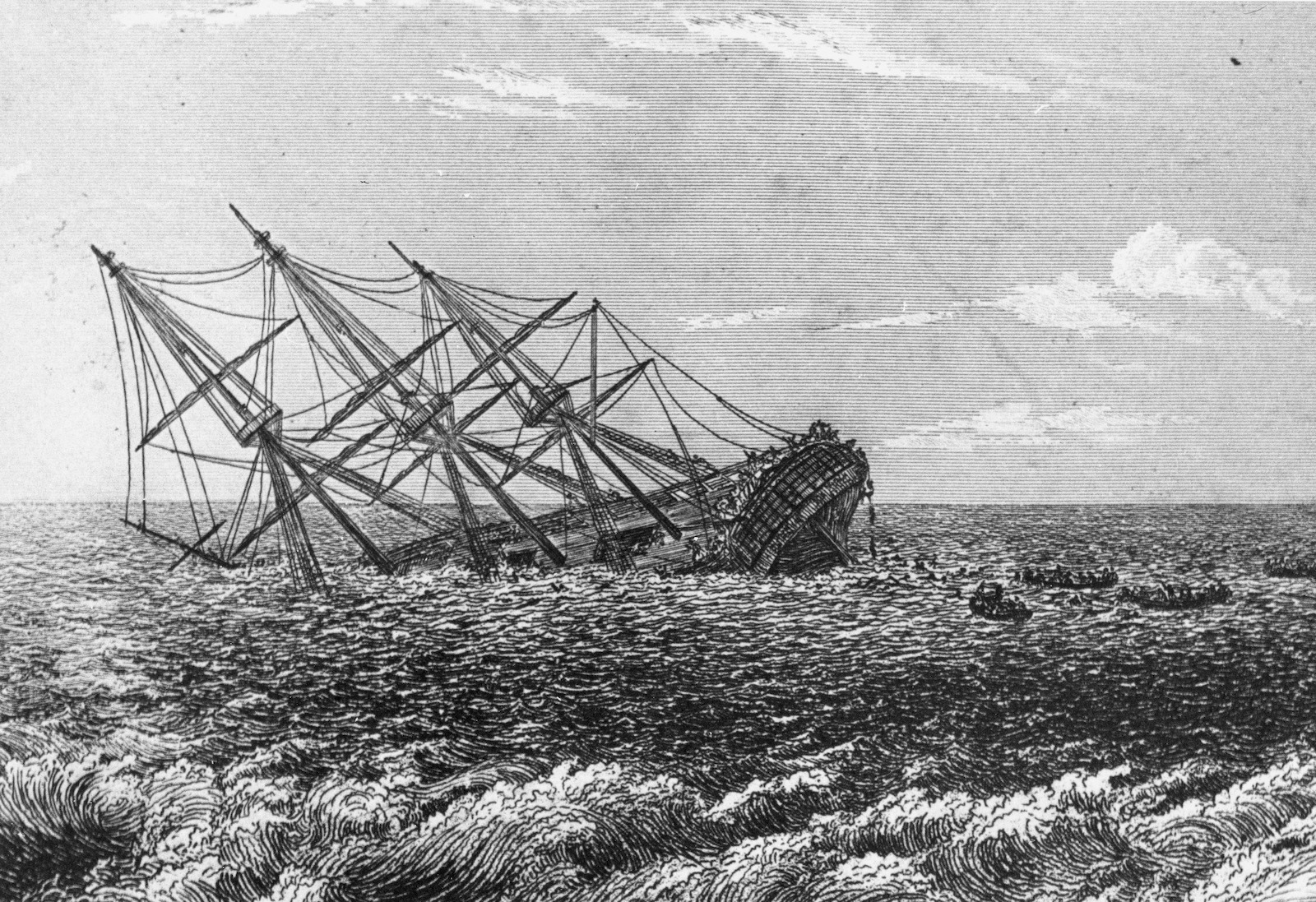

Etching of the Pandora (ship) 1831. John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland. Negative number: 66925.

Trundle’s feelings reflect the contemporary changing definition of loneliness. From the mid-19th century, as religion lost favour and industrialism reigned,[9] Victorians reinterpreted the emotion to ‘encompass a great sadness, said to be instigated by “closed-door” city-living’.[10]

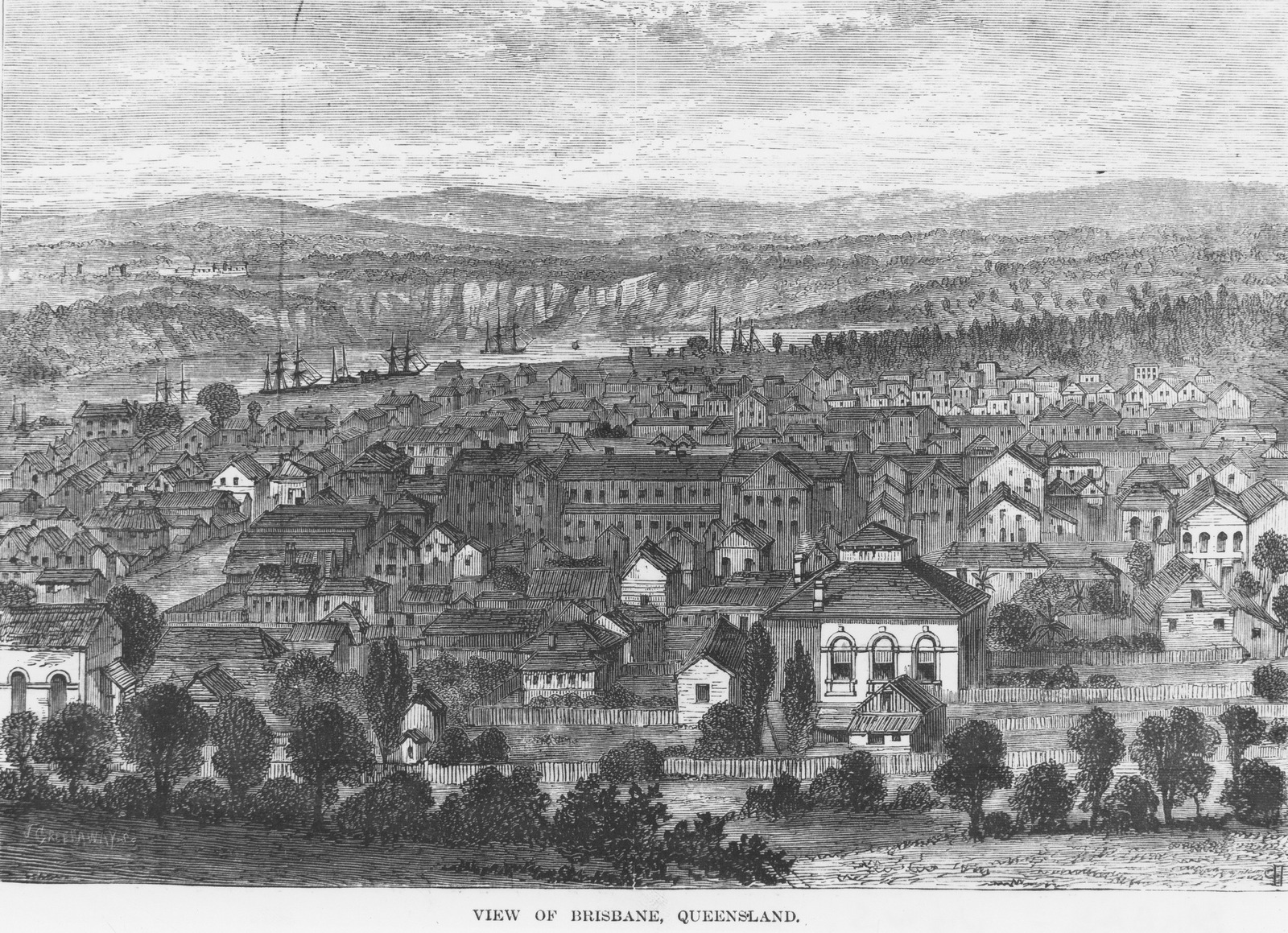

Woodcut of Brisbane in the 1870s. John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland. Negative number: 51302. Negative number: 66925.

Quite away from city living, and in our more recent history, 16-year-old Queensland sailor Jessica Watson reflected on her predecessors’ emotions during her world-record solo circumnavigation in 2010, writing: ‘…when the wind is strong, the sea is building and all I can see in any direction is an endless ocean meeting an equally endless sky, the feeling of being a small part of something much bigger surely would have been similar.’ Watson’s observation echoes poet Zora’s Cross’ reflections on the vastness of our interior worlds.

Watson continues: ‘Some people find the thought of being alone for a long time really frightening but it never really scared me.’ She concludes: ‘When I’m sailing the world slows down and what matters, if I let it, is only that moment.’ [11]

Perhaps courage, fortitude and loneliness sit together more closely than we might first think.

Wake from a boat on the ocean at Peel Island. Morgan Gabriel, 2018, Acc 27550, Dr Morgan Gabriel Collection, John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland. Image number: 27550-0014-0077.

References

[1] Songs of Love and Life, Zora Cross, Angus and Robertson Limited, Sydney, Australia 1917, p.49

[2] The Shelf Life of Zora Cross, Cathy Perkins, Monash University Publishing, Victoria, Australia 2020, pp.80-81

[3] The Central Queensland Herald (Rockhampton, Qld: 1930-1956), Thurs 19 Nov 1931, p.11

[4] A Biography of Loneliness, Fay Bound Alberti, Oxford University Press, London, 2019, p.10

[5] Ibid., pp.3-4

[6] Ibid., p.20

[7] Transcript of the Diary of Fanny Trundle, 19 Oct 1873, p.8

[8] Transcript of the Diary of Fanny Trundle, July 1877, p.9

[9] A Biography of Loneliness, Fay Bound Alberti, Oxford University Press, London, 2019, p.10

[10] The Book of Emotions, Tiffany Watt-Smith, Profile Books LTD, London, 2015, p.167

[11] True spirit: the Aussie girl who took on the world Jessica Watson, Sydney: Hachette Australia; 2010, p.180

About the author:

Greer Townshend was the 2022 Mittelheuser Scholar in Residence for her project, I Feel You: Discovering Collections Through Emotion.

Read her other blogs

Watch Greer's Research Reveals talk.

Research Reveals 2024 - Morning Session. 23:46 Greer Townsend, Mittelheuser Scholar in Residence. Project: I Feel You: Discovering collections through emotions.

Comments

Your email address will not be published.

We welcome relevant, respectful comments.