Ever Since I Saw the Wildflowers on the Channel Country… from thousands of miles away

By Dr Max Brierty, 2022 Monica Clare Research Fellow. | 6 June 2025

Dr Max Brierty - 2022 Monica Clare Research Fellow. Project: Mipa Mipumani: The Colonisation of Kullilli Country in South-West Queensland.

You’ll never see anything like this again…. Those words are circling round my head as I sit down to write this post. Why’s that, I wonder?

This is my third and final post for my 2022 Monica Claire Research Fellowship here at the State Library of Queensland. The project itself has been looking at the colonisation of Kullilli Country – ancestral homelands for me and much of the Aboriginal side of my family. So you can get your bearings, Kullilli Country is about a thousand k’s west of Brisbane in the Channel Country bioregion.

Maybe those words, You’ll never see anything like this again, have come back to me now because they remind me of how this project began to take on a new momentum. They were beamed across the television in a news report about the spectacular explosion of wildflowers in the Channel.

Wildflowers featured on page 23 of The Queenslander Pictorial, supplement to The Queenslander, 22 February 1919. (2014). John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland.

That was more than a year ago now. At that time, I was waylaid on the other end of the world; no I wasn’t. Well, the wildflowers put me in two minds. See, I was in the privileged position of being in the United States doing research at a very privileged university. At the same time, I had been bushwhacked by a cold, icy winter. Even after the snow melted, homesickness stuck around. I found myself watching Australian television online hoping for a cure. But seeing the wildflowers from thousands and thousands of miles away had the opposite effect, especially when it was preceded by those words: “You’ll never see anything like this again.”

Maybe there is something to the push and pull, back and forth, of great physical distance and the up-close, in-your-face proximity of the wildflower footage which gave extra weight to those words. But there is something to the wildflowers themselves. There’re the seeds which lay dormant for who knows how long, waiting for the next rains and floods to arrive. With the waters, they leap up from the ground in a flash, bursting into the world in seas of colour. They might as well be lightning shooting up from the ground.

Out of the research I have been undertaking for the Monica Claire fellowship, I have been writing a book called “Wildflower Country” which looks to tell stories about the colonisation of Kullilli Country and the Channel. My hope is that the writing can in some way or another run with the same creative energy as the wildflowers, even as it comes face to face with the violence which colonisation has brought to bear on people, animals, plants, waters, land… everything that belongs together in the great big pattern of Country.

Being creative with my storytelling means that what I am looking to do is not a typical kind of history writing. History tends to hold the past at arm’s length whereas being creative might just show us that the past never really passed at all and that it is very much here with us in the present, even if it is alive in ruins.

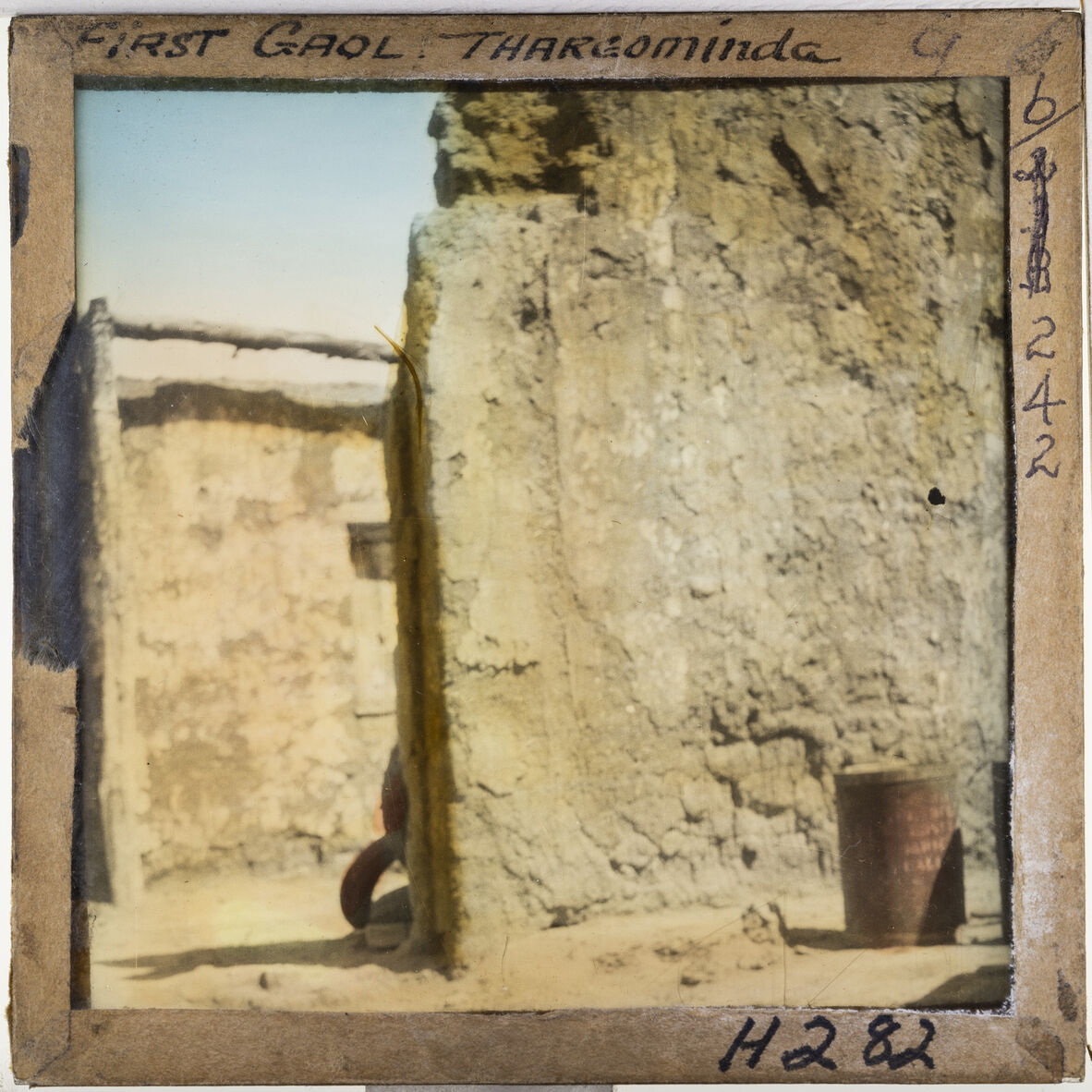

Remains of Adobe (brick) walls of the first jail in Thargomindah, South West Queensland. Part of Item 06, 33656 Royal Geographical Society of Queensland lantern slide collection. John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland.

Not a history, no. The idea being that there is more meaning to be found out in storytelling than a strict adherence to mere “facts.” It’s not just the case that facts can only take us so far, but that it will want to pull the writing down a particular path – or box it in, as if to jail it up.

That’s not to say that I am looking to write fiction. Believe me, the stuff I have been finding in the archives can tell stories stranger than fiction ever could. The creative part arrives in being open to realising just how surreal the past and present really are. Another side of it is being able to run with the images that arrive out of the research. Rather than taking hold of archival materials and wielding them as facts, I am wanting to throw myself into those materials so they can lead the way.

Photograph of a camel (name unknown, poor fella) around Cooper Creek. 30123 Far South West Queensland photographs, John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland.

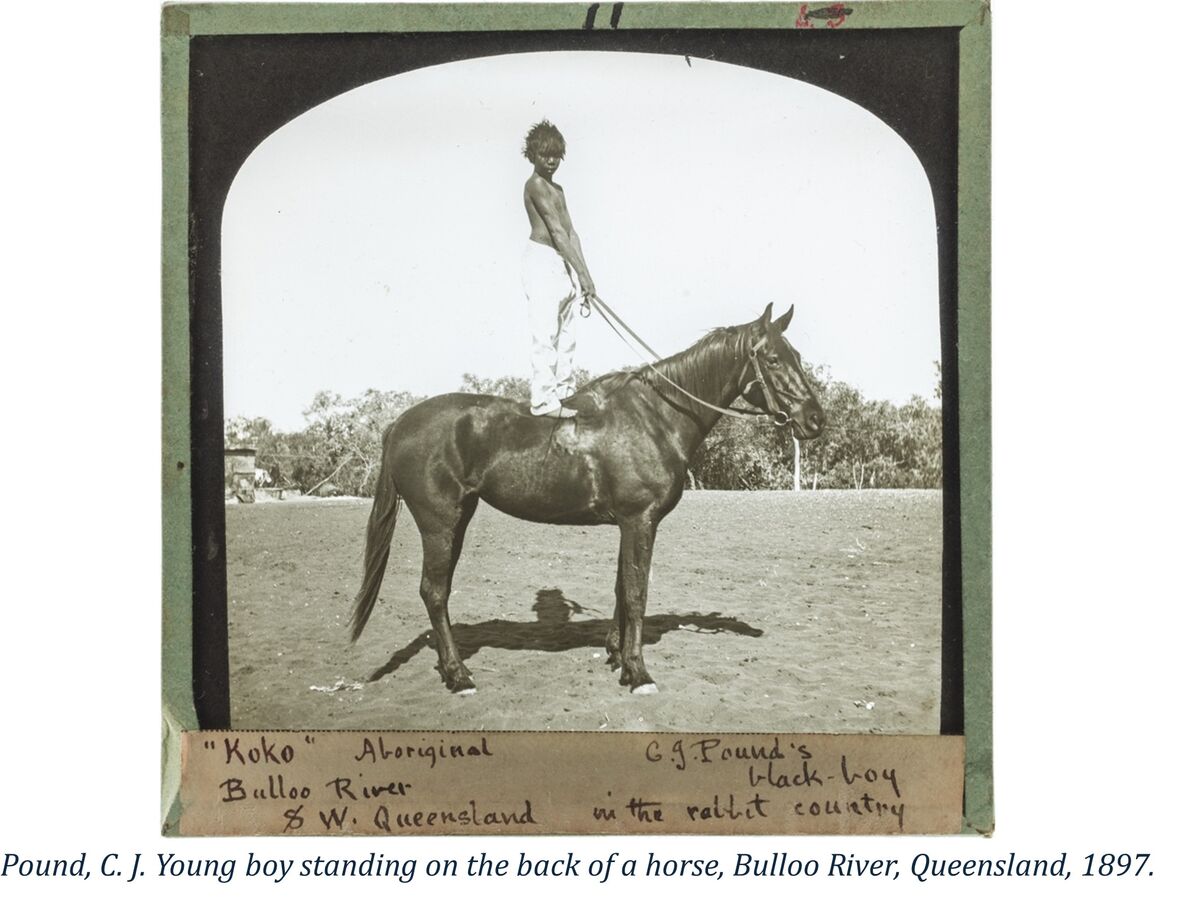

Pound, C. J. Young boy standing on the back of a horse, Bulloo River, Queensland, 1897. 6529 Charles Pound lantern slides, John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland.

This is how I came to dream into images, as I talked about in my previous post, “Unpacking my trolley.” I spoke about how I have been especially drawn to the photographs taken by C J Pound, a bacteriologist and amateur photographer who was on Kullilli Country in the 1890s doing experiments on rabbits. The photograph of Koko, an Aboriginal boy, standing on the back of a horse is one such dreamful image. Where would this pair take us if we followed them?

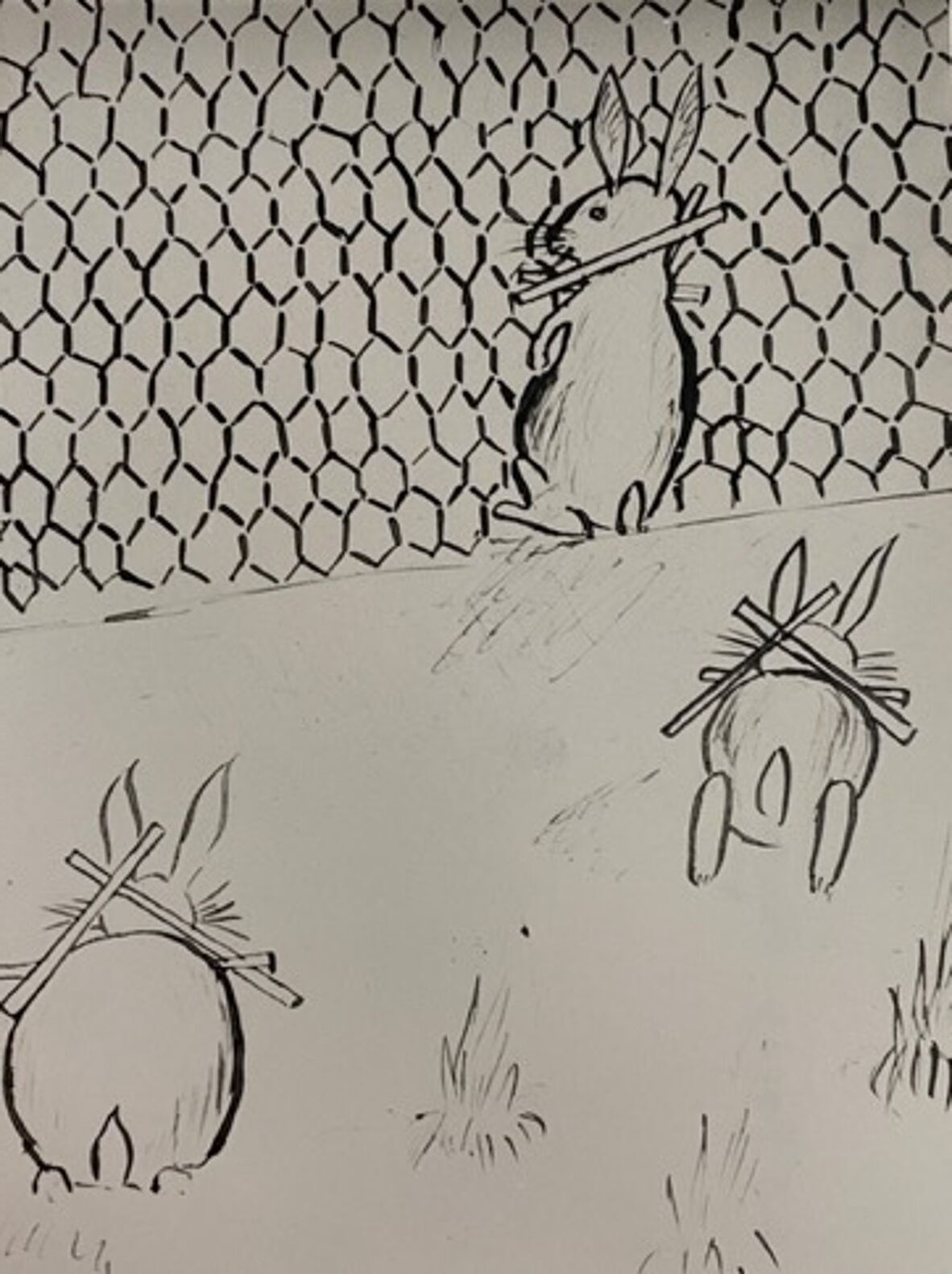

A suggestion for rabbits that get through netting fences by camp cook (H.C.). 6529 Charles Pound lantern slides, John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland.

How about all the other images, and not just those which arrive out of photographs, but also drawings, diaries, memoirs, maps...? What are we to make of this drawing of rabbits in triangle collars, for instance? I came across this drawing in a folder of some of Pound’s photographs. It gets thinking moving. Within it, there’s stories of rabbit plague then and now. Swirling round within those stories are questions about the various roles that animals, both feral and domesticated, have played in the colonisation of Country. Add to that, the boundless pursuit of mastery over Nature, like Pound’s use of science to try to end the rabbit plague and make the land more productive.

A few months back in my Research Reveals I promised a post on myth, magic and make-believe. As well as being caught up in the stories rising up out of Pound’s rabbit experiments and his rabbit camp, I have also been reading Alice Duncan-Kemp’s writings on the Channel. Maybe I was a bit unfair in my last post here when I said that Duncan-Kemp blended real and make-believe together in giving form to myth. There’s interesting research coming out which gives weight to a lot of what she was writing about.

What I was getting at, more so, was the way storytelling works in colonisation. As in, the stories settlers tell themselves and others. It seems to me that stories are a way of fixing meaning. From meaning, belonging can be fixed as well. But so too can the justification about the way things are to be done and how Country is to be treated.

See, if you tell yourself that Country is just “land”, empty land, or part of a singular Nature which has to be mastered, possessed, and made productive then you are telling yourself a particular story. This story didn’t arrive out of thin air. Just because the story is told over and over again, doesn’t mean it’s a good one.

There are other stories which already belong here, and to Country, and if we listened to them, we would recognise that there is a different way to do things. Other systems and ways of living with Country are possible. And that’s where storytelling comes in.

Maybe the magic trick that certain tall tales come to play on Country can be outdone by telling new stories, old stories, and stories living in between. They have to be stories which bring meaning, creating new possibilities and energizing sleeping ones – just like the wildflowers leaping up from the ground as lightning after the rain.

Dr Max Brierty

2022 Monica Clare Research Fellow.

The Monica Clare Research Fellowship is generously supported by the Siganto Foundation.

Other blogs

- Read other blogs by Dr Max Brierty

- Read other blogs about Queenslan's First Nations history by past Monica Clare Research Fellows.

Dr Max Brierty's Research Reveals talk.

Comments

Your email address will not be published.

We welcome relevant, respectful comments.