Unpacking my trolley: A “wild” archive of stories on the Channel Country

By Dr Max Brierty, 2022 Monica Clare Research Fellow | 21 February 2025

Dr Max Brierty - 2022 Monica Clare Research Fellow. Project: Mipa Mipumani: The Colonisation of Kullilli Country in South-West Queensland.

Boxes of books, photographs and documents have been piling up on my trolley in the Neil Roberts Research Lounge at the back of the John Oxley Library. Over the past few years, I’ve gathered up a wild archive of materials for my project on the colonisation of Kullilli Country in south-west Queensland. Kullilli Country is in the Channel Country, a bioregion so named for the intertwined grooves and rivulets that carry waters inland, towards places like Kati Thunda (Lake Eyre).

I call this archive “wild” because the materials stacked on my trolley are all speaking different stories and of different times, each following their own rhythm and key. They resist being pinned down and controlled.

Neil Roberts Research Lounge with trolleys of collections used for the research projects of State Library's Queensland Memory Awards fellow.

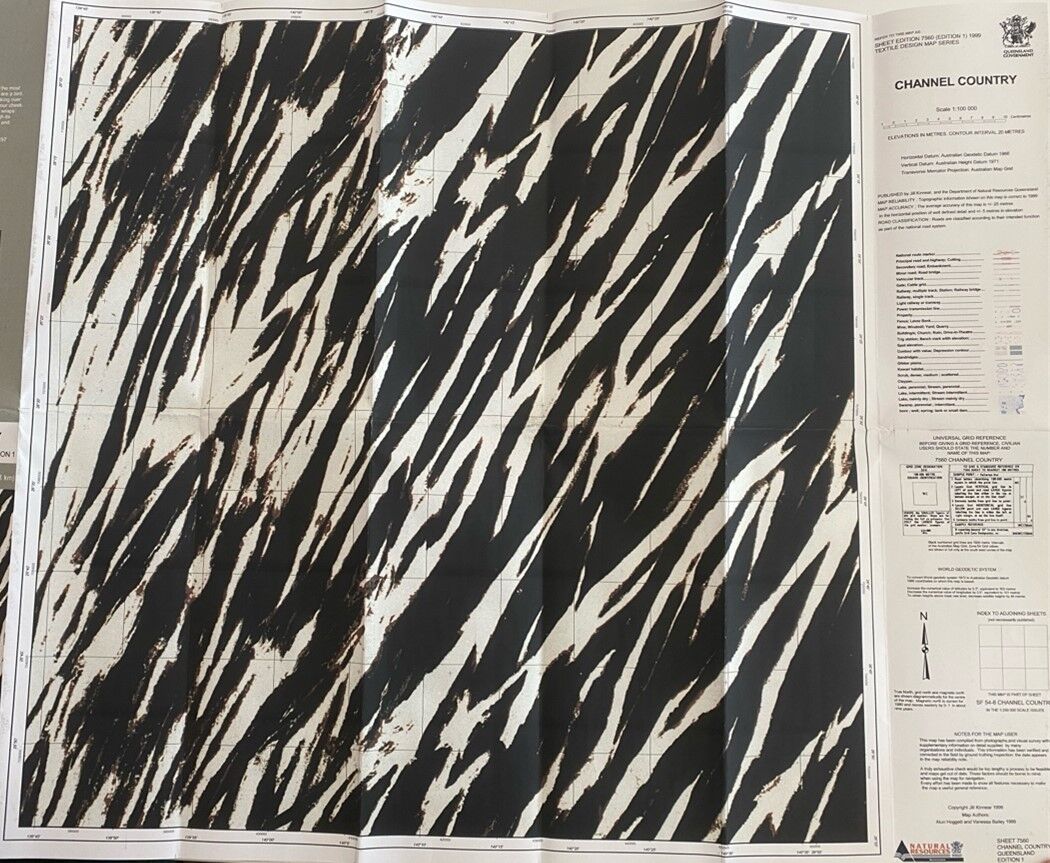

Check out this tongue-in-cheek map of the Channel Country.

Kinnear, J., & Queensland. Department of Natural Resources. (1999). Channel Country, Queensland. J. Kinnear and the Dept. of Natural Resources Queensland.

For some time, I looked at this wild archive as fragments of a bigger picture, a once ‘complete’ picture, which now has plenty of missing pieces and silences within it.

There was fear in that. The fear was in not being able to do justice to the story of ancestors, of Country and my community. It was a fear of not getting the answers that I had been chasing to the questions I had been running with for a long time; questions which led me into this project and the Monica Claire Research Fellowship in the first place.

The longer I sit with this wild archive stacked on my trolley the more I recognise that it cannot be written as a “history” of colonisation in the Channel. Well, not a typical kind of history, at least – not the kind of history that is disciplined by a big H, claiming to have straightened out all the curly questions by “leaving no stone unturned” and writing the past exactly “as it was”.

Something mysterious is stored in the wild materials piled on this trolley. Something powerful is at play. I know now that my writing about it (with it) means playing along.

I want to unpack some of this wild archive, not so much as to give a complete inventory, there’s no time for that, but to speak to some of the directions that it is taking me.

The usual suspects are there, of course, stomping around the trolley. There are the diaries of early European settlers to the Channel, as tragic as they are often tedious. At times it is because they are so tedious that they are so tragic, to the point where they become silly, but then the real tragedy makes itself known again. (1)

Vincent James Dowling’s limerick about three flies zipping around a butcher’s shop would have to take the cake. Dowling is credited as being one of the first “settlers” to “settle” Kullilli Country and, as is typical of ‘pioneers’, questions about the violence he relied upon still require our attention (as I have written about in “The Man with a Hole in his Hat”). The silliness of his rhyming is a reminder of the intense boredom and emptiness settlers like him seemed to have wrestled with as they strayed around the frontiers. It makes you wonder what possessed them to do what they did in the first place. But also, of where the violence goes. Surely it is there in his writing even though he does not write about it (violence), no less than it is stored in the Country itself?

This wild archive speaks to the strength of Indigenous men, women and children to survive and adapt to their world colliding with a modern, colonial one. Rifling through the memoirs of settlers from the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries have offered many insights into this. In a lot of ways, these materials break away from the standard historical narrative that paints Indigenous people as having been conquered by a supposedly ‘superior’ society. They add some depth and complexity to stories of what life was like for Indigenous people working on and living beyond the pastoral stations on the Channel. But often this requires reading against the grain as much as between the lines.

What has been particularly striking to me is the level of agency and mobility that many Indigenous people expressed in the face of colonisation on the Channel. It remained so generation after generation. This all makes sense, I guess, when you recognise that the pastoral industry would have collapsed without them. One line that I am currently following in this wild archive, thanks to the advice of historian Thom Blake, are those Indigenous families on the Channel who owned their own businesses as drovers.

But I can’t shake this one image. It came to me in reading an account of Nockatunga station, at the western edge of Kullilli Country, in the early twentieth century. (2) The account tells of Indigenous people heading off in big convoys in the summertime to do cultural business and see family. Many rode their own horses. Some even drove their own cars. Their own cars! It is a living image. And it is an image that is made all the more powerful when we recognise that this was taking place during the so-called “Protection” era.

Protection was a time when the Queensland government, like other settler governments, had laws and policies in place which tried to control almost every aspect of Indigenous peoples’ lives. It saw thousands of Indigenous people being “removed” to government reserves and missions. Many Indigenous families, mine included, were broken up during those times, caught by forces that have come to be known as “Stolen Generations” and “Stolen Wages.”

Beneath a pile of agribusiness reports, talking in dry and matter-of-fact tones about economic development and environmental management on the Channel, there is a big grey box which screams the history of Protection. It contains the papers of Archibald Meston, who some see as the architect of Queensland’s Protection system. Badtjala historian and artist Fiona Foley has written all about Meston’s deeds, including in Bogimbah Creek Mission, a book she wrote as part of her 2020 Monica Clare Research Fellowship.(3)

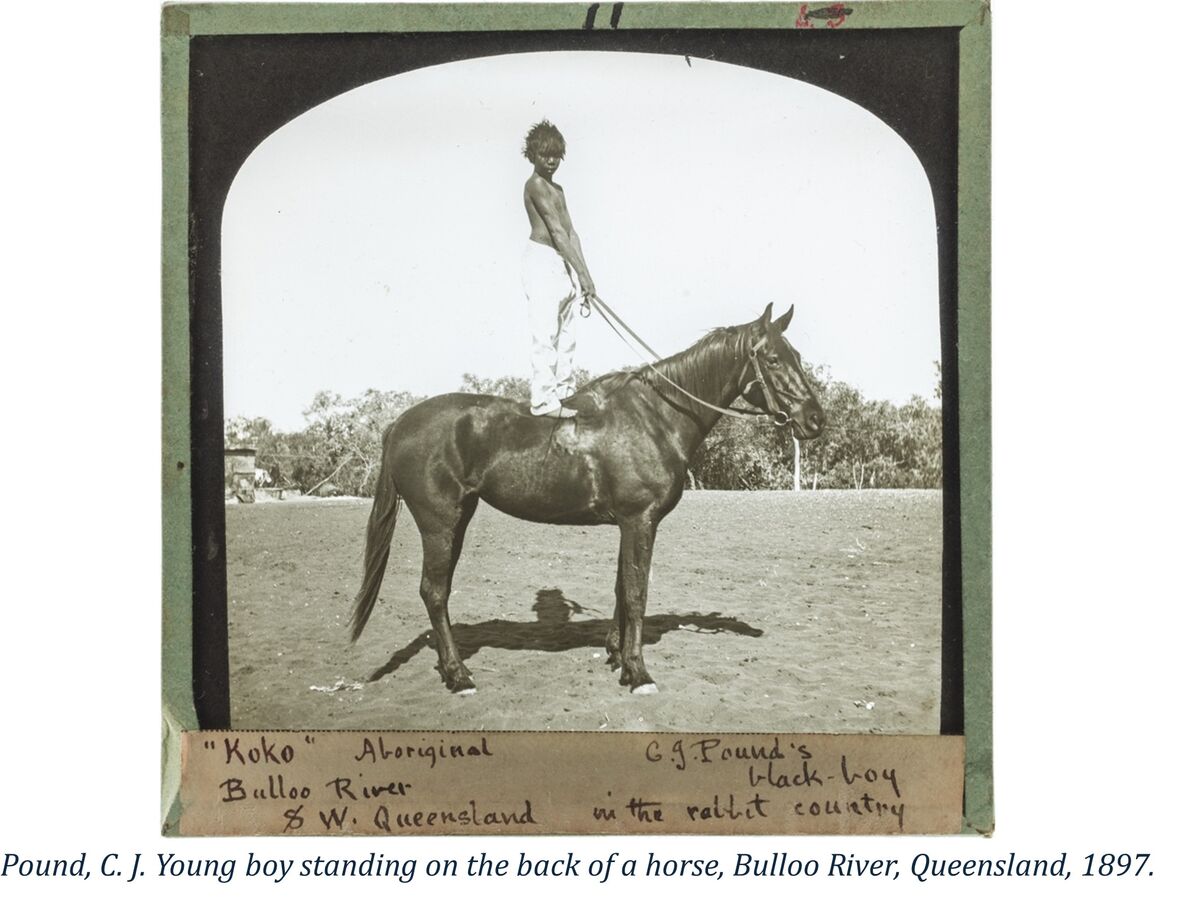

Beside Meston’s papers is another big grey box. It is filled with a handful of photo albums. There are a bunch of photographs, amazing photographs, of Indigenous people on Kullilli Country. I can’t say for certain that they are Kullilli people, not yet anyway. This image of Koko, a nine-year-old Indigenous boy, standing on the back of a horse at Bulloo River station jumps out at me. The pair look as though they could take off for a few laps around the stable yards any minute, only to leap the fence and keep on going. There is freedom in that image. It is a freedom that is made all the more potent when thinking about all the forces that were at play around them. This is the kind of freedom that cannot be contained or captured. It cannot be stolen.

Pound, C. J. Young boy standing on the back of a horse, Bulloo River, Queensland, 1897. 6529 Charles Pound lantern slides, John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland.

The photograph itself is one of a few dozen taken by C J Pound, a bacteriologist and amateur photographer, in the 1890s. Pound made his way out to the Channel as part of his journey around Queensland. He was trying to figure out a way to control the rabbit population with Chicken Cholera. It’s no surprise that there are plenty of photographs of rabbits, then, along with the traps he laid and the damage they had done to the Country. Interspersed through the album are photographs that he took of himself, like this one of him under an Emu-apple tree.

Pound, C. J. Emu apple tree growing at Norley Cattle Station, Queensland, 1896. 6529 Charles Pound lantern slides, John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland.

Lately, I have been caught up with thinking of the ways that settler culture seeks mastery over Nature and the landscape – something I will speak more to in my next blog post. Pound’s use of modern science is a case in point. But so are the enchanted, literary writings about the Channel by figures like Alice Duncan-Kemp. I’ve slowly been working my way through a stack of her books, stowed away on the trolley of this wild archive, after my friend Stephen Muecke handed me a copy of Duncan-Kemp’s book Where Strange Gods Call. Duncan-Kemp writing mixes together what is real and make-believe in ways that give life to myth. And myth is a powerful thing. Just as powerful, perhaps, as modern science when it comes to mastery over Nature. But that is for another time.

I have been writing a book of my own about this project for the University of Queensland Press called “Wildflower Country”, which should be published next year, in 2026. What interests me in telling the story about the colonisation of Kullilli Country and the Channel is not just writing about the people swept up in it, but the place of Country in that story. Country, in an Indigenous sense of the word, is a living body that is patterned together. So, how might we go about sharing its experience and its story? This wild archive on my trolley at the back of the John Oxley Library can only tell me so much. What has to follow, of course, is actually going there, returning to Country so that it can share its story—and hopefully that can be with other Kullilli people, family and kin.

Dr Max Brierty

2022 Monica Clare Research Fellow.

The Monica Clare Research Fellowship is generously supported by the Siganto Foundation.

Other blogs

- Read other blogs by Dr Max Brierty

- Read other blogs about Queenslan's First Nations history by past Monica Clare Research Fellows.

References

- Here I am taking inspiration from Michael Taussig’s writing in books like The Nervous System (New York: Routledge, 1992) and Palma Africana (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2018).

- Hughes, R. (1982) Historical notes on Nockatunga Station / Reginald Hughes. 1982, John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland.

- Foley, F. Bogimbah Creek Mission: The First Aboriginal Experiment (Booral: Pirri Productions, 2021). See also, Foley, F. Biting the Clouds: A Badtjala perspective on the Aboriginal Protection and Restriction of the Sale of Opium Act, 1897 (St Lucia: University of Queensland Press, 2020).

Dr Max Brierty's Research Reveals talk.

Comments

Your email address will not be published.

We welcome relevant, respectful comments.