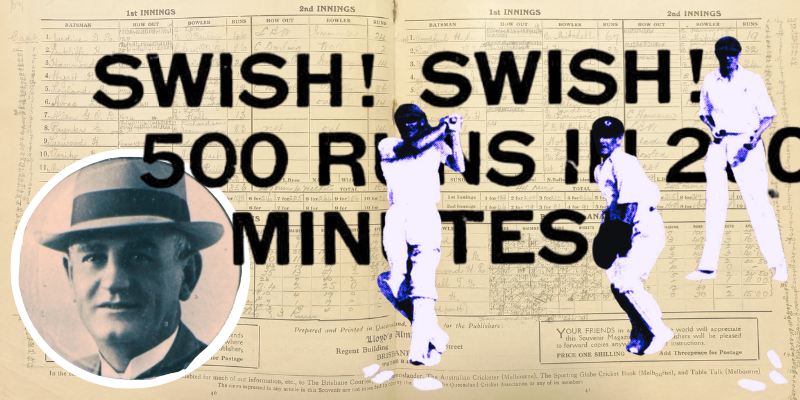

Brighter at any cost: A.J. Hunting and the real story of one day cricket

By Chris Currie | 15 April 2025

Did you know Australia’s first one day cricket match was played at the Ekka grounds in 1933? The scheme was the brainchild of A.J. Hunting, one of Queensland's most prolific and imaginative entrepreneurs, and the story is just as wild as a limited overs run chase ...

While many of us equate the beginning of limited overs cricket with Kerry Packer’s breakaway World Series competition, in fact Australia's first “one day cricket” match was played in Brisbane – at the iconic Ekka grounds – over 30 years before the bright lights and big hits became prime time entertainment. The man behind it was a remarkably relentless inventor and entrepreneur whose amazing story put him quite literally ahead of his time.

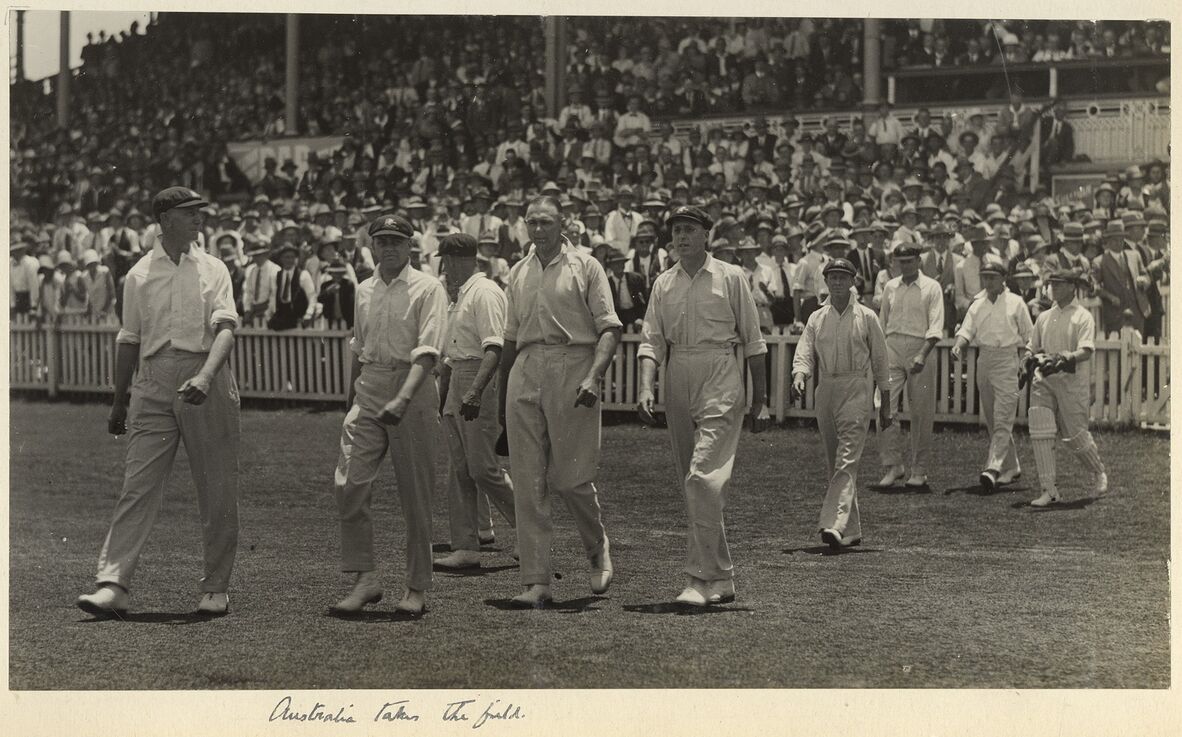

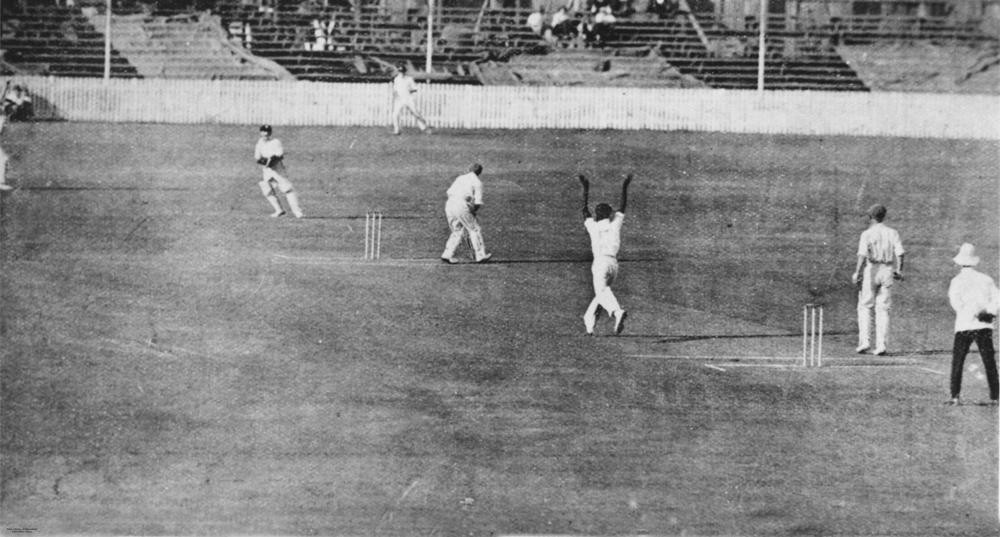

Cricket in Queensland in the 1930s was a strictly amateur, unpaid sport – a colonial inheritance of the so-called "gentleman’s game". The Sunshine State had only been admitted to the domestic Sheffield Shield competition in 1926, with the first international test match played in Brisbane two years later at the Exhibition Ground.

The Australian Test cricket team walks out to field at the Exhibition Grounds, for Brisbane's first Test match in 1928.

Despite the relative success of Test cricket, there were already calls to speed up the game to make it more attractive to the public. Enter relentless inventor, entrepreneur and sports promoter Albert "A.J." Hunting.

In June 1933, facing a decline in his wildly successful speedway racing enterprises, Hunting proposed a series of local matches between professional, paid teams over three hours on Saturday afternoons at the Brisbane Exhibition Ground.

A.J. Hunting ca. 1940s. Photograph from Worldwide Speedway Adventurer: The AJ Hunting Story by Tony Webb.

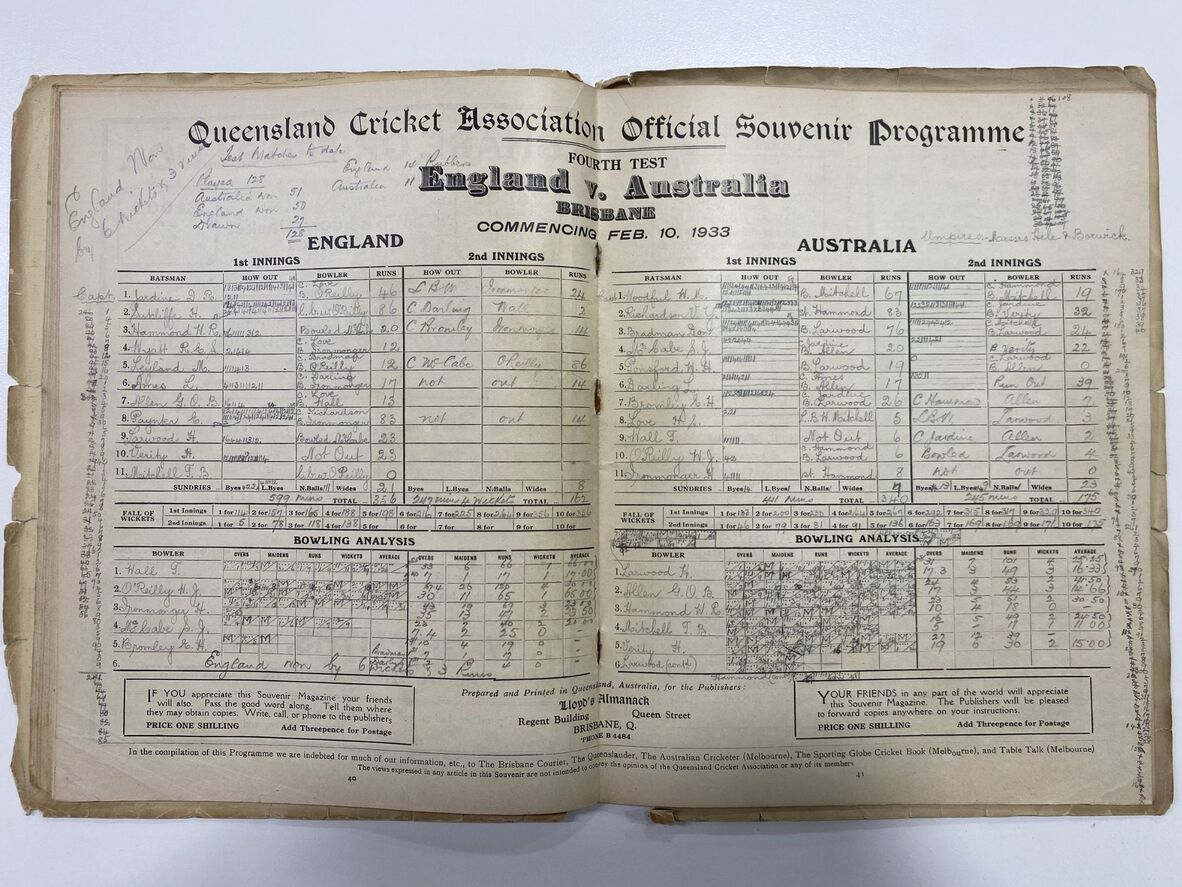

Pages of Hunting's diary – part of an extensive collection of his personal papers held at State Library – reveal his early thoughts about cricket’s lack of entertainment, after watching the seven day 1933 Ashes Test between Australia and England at the Gabba (ironically won by England off a six into the members' stand):

"Just imagine going to a talkie and finding it 20% silent or worse, for such were the recent tests ... one over out of four a “dud” [or] “maiden” from the general public’s point of view.

Take out your wallet and wait for 1 minute to go by and see how tedious present day Cricket is, for the scoring at the recent test was 1 run per minute – is it any wonder that Club Cricket is not patronised.

Hundreds of players in Brisbane, Sydney Melbourne ... etc are ready to adopt the new style of cricket, believing that it is what the public want, and they are prepared to join it."

Hunting’s vision for a new game included four innings being completed within a three-hour period, with each batsman receiving ‘no more than 10 or 20 effective balls per innings’ to encourage them to ‘open out and hit’.

Further encouragement was a merit-based payment system for players, reported in the Telegraph, including two pounds for every six hit, and 7 shillings sixpence for bowlers who could rattle a batsman’s stumps.

Completed scorecard to the 1933 Gabba Test Match. From the Q.C.A.’s Official magazine and programme fourth test match Brisbane, held in State Library collections.

A no to "circus cricket"

Hunting faced considerable opposition from the Queensland Cricket Association (QCA). Despite his offer of a licence fee for every “one day cricket” match played, the Association offered only a scathing response.

Mr. F.J. Bardwell, chairman of the QCA’s Warehouse Division (who were reportedly counting on the same venue as Hunting’s new venture that same summer), predicted the scheme would last no longer than six weeks, and described Hunting’s plans in less than complimentary terms:

‘Unfortunately he is entirely off the track in his interpretation of the psychology of the cricket crowd. He does not realise that cricket fans, while they may desire the infusion of a livelier spirit in the game, will not tolerate any drastic alteration to the laws which have stood for many years, and they certainly will not take kindly to the circus cricket that this ten-balls-and out business seems to promise. What a prostitution of our fine old British game!’

Moreover, the QCA promised to ban any players signing up for Hunting’s competition. Weeks of thinly veiled op-eds between Hunting and Bardwell were devoted to whether the QCA representative at any stage wished Hunting “good luck”. The matter seems to never have been resolved.

Play ball

Nonetheless, by August Hunting had formed a company – Professional One Day Cricket Limited – promising “brighter cricket at any cost”. He secured a month’s lease at the Brisbane Exhibition Grounds and began to explore similar competitions in Sydney and Melbourne.

Despite the QCA’s promise to ban any players joining the new competition, Hunting soon announced a number of signings for his new league, including Queensland Sheffield Shield players Herbert Gamble (the state's best bowler the previous season) and Leonard Waterman – perhaps most well-known for taking the catch that dismissed Donald Bradman for an infamous duck off the bowling of Aboriginal fast bowler Eddie Gilbert).

Leonard Waterman catches Don Bradman off Eddie Gilbert, 1931.

After an unofficial hitout on Saturday 23 September, in which 496 runs were scored in 171 minutes, Hunting proudly proclaimed that ‘while the Q.C.A. A grade batsmen could average only 248 runs for the afternoon on four grounds, the League players scored exactly twice that number in a shorter time.’

The league’s official opening day was to feature the Bohemians taking on the Pioneers, with each team facing three innings each, in which batsmen would only face ten balls unless dismissed first. At the end of the second innings, the remaining time would be divided between both teams.

The “payment by results” numbers were also now settled:

- 10 shillings for each six scored

-

2 shillings for each four

-

£3 for a hat trick

-

£1 10s for each two wickets in succession taken by a bowler

-

20 per cent of the net gate receipts to the winning team

-

10 per cent to the losing team.

In details prescient of today’s Twenty20 cricket, each player would wear a number on their back to identify them and batters were instructed to hurry on and off the field.

Of course you do.

Heavy rain delayed the proposed start, but the league was ready to go the following Saturday.

Only three days from the season launch, Herbert Gamble announced he would be withdrawing from the professional league to rejoin his existing team Toombul in the QCA competition. Gamble stated he had that morning been offered a job that precluded him from playing professional cricket. With a signed contract from Gamble in place, Hunting reportedly began exploring his legal options.

On Saturday 7 October 1933, “under ideal weather conditions”, between 800 and 1000 spectators watched Australia’s first game of “Professional One-Day Cricket”. When Bohemians batter A.C. Wright hit the league’s first six, A.J. Hunting himself marched out onto the pitch to present him a 10 shilling note.

"We read a story one time of a man who had only one hour to live. The professional cricketer's life at the crease may be shorter than that, but it is undeniably sweet." From The Truth, Sunday 8 October 1933.

Over 500 runs, 200 minutes, 39 fours and 1 six later, Bohemians won the ‘afternoon of entertaining, if not altogether scientific cricket’ by 33 runs. As a comparison, it was reported the amateur cricket played that same day yielded an average score of 272 runs.

The reception in the press was lukewarm, with many reports still unbelieving that this new form of cricket could capture the public imagination.

Brisbane's The Telegraph’s reported on 9 October that while 'the game is certainly livelier to watch' and 'the ball is hit harder and oftener', many of the new features were 'not in keeping with the dignity of the game'.

Illustrator and artist Ian Gall gives his take on professional one day cricket.

Hunting provided a detailed rebuttal to his critics the following Tuesday, promising that he had ‘not yet ceased experimenting’ with his product. Indeed, by the next match the 10 ball limit had been removed. A new rule allowed a batsman to stay in as long as he liked, so long as he was able to ‘score off at least five out of every ten balls he receives.’

The third weekend featured spectacular hitting from former Queensland player Gordon Amos, with two of his five sixes disappearing over a concrete wall into Gregory Terrace.

At the end of October, Hunting was reported to be travelling to Sydney to drum up support for interstate league matches.

By November he was back in Brisbane, sharing his feelings on a Sheffield Shield match between Queensland and New South Wales. After watching a day where 428 runs were scored (including 200 from Don Bradman), Hunting offered only regret that ‘the bowlers were having their hearts broken by ‘maiden overs’ as the batsman would not ‘take the risk’ and give ‘the chance’ which the public so enjoy.’

Gordon Amos and Leonard Waterman in action.

The end of the innings

By the end of November, the wheels appeared to be coming off Hunting’s cricket experiment. The Telegraph reported that ‘less than twenty spectators’ were in attendance for the 18 November match, which had already been moved to the smaller No.2 oval.

On 21 November, Hunting sent a letter to the QCA once again asking they reconsider their ban on professional players, with his rather extraordinary central argument being that as none of the players had yet been paid, they should not receive any punishment for their involvement in One Day Cricket.

‘In support of this application,’ he wrote, ‘I may say none of the players who have played at our meeting have received any cash consideration for their play on the field.’

It turned out that the ten-shilling note Hunting had publicly presented to A.C. Wright for the first six hit was the only payment made to players. The QCA concluded that ‘no action would be taken’.

On Sunday 3 December, The Telegraph reported that professional one day cricket was ‘dead, leaving few mourners except the participants on whom still rests the ban of the Q.C.A.’.

With professional cricket officially deceased, the Q.C.A. lifted their ban on Tuesday 3 July 1934.

The inventor

Undeterred, Hunting established a golf course at Windsor in 1939 with floodlights for night-time play, although financial troubles forced its closure in 1940. By this time, he had also returned to the Exhibition Grounds to run a series of short-lived boxing matches.

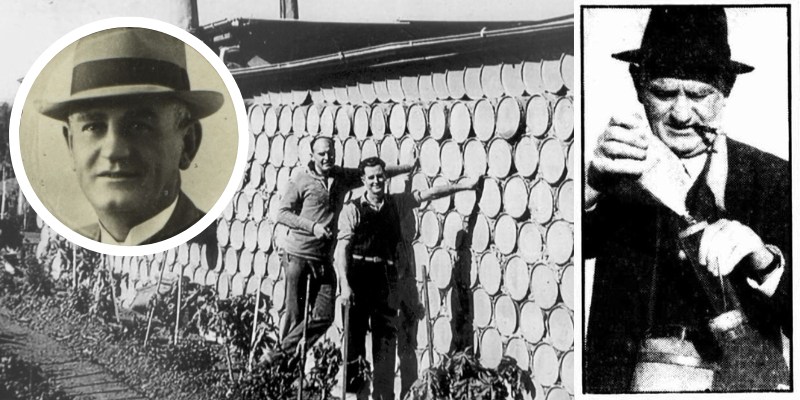

During World War II, Hunting spent years petitioning the military to approve various inventions for troops, including a portable flamethrower, an unsinkable canoe and an automatic parachute-opening device. While his efforts were unsuccessful, he did manage to sell water-cooling crystals to the dairy industry. In 1946, he announced that he had erected a toy factory, constructed of 2,000 two-gallon drums.

A J Hunting (inset: from Davies Park Speedway photomontage; his toy factory built from 2,000 two-gallon drums and; demonstrating his water-cooling device.

Later that year, Hunting passed away. Despite expressing remorse about his many failed business attempts, his enterprising and entertaining creations, schemes and ventures – not least of which the prototype for professional limited overs cricket – make him one of Queensland’s most memorable figures.

FURTHER RESOURCES

-

A.J. Hunting papers 1930s-1960s, 1930-1969, John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland

-

A. J. Hunting: The man who commercialised speedway in Australia (video), 2017, Sarah Scragg, State Library of Queensland

-

A J Hunting and Speedway, State Library of Queensland website, accessed 14 April 2025

-

England v Australia 1928 : test cricket comes to Queensland, State Library of Queensland website, accessed 14 April 2025

-

Magnificent Makers web page (archive), State Library of Queensland website, accessed 15 April 2025

-

Official magazine and programme fourth test match Brisbane, 1933, Queensland Cricket Association, Brisbane: Lloyd’s Almanack, John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland

-

Trove website (various pages), accessed 15 April 2025

Comments

Your email address will not be published.

We welcome relevant, respectful comments.