Blue coast caravan : Queensland road trip 1930s style

By Simon Miller, Library Technician, State Library of Queensland | 13 December 2012

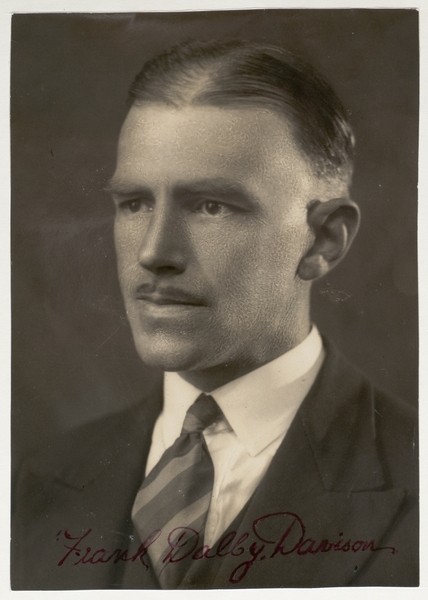

Summer holidays are upon us and many will be taking to the roads. No doubt many will complain about the state of the roads, particularly the Bruce Highway that snakes along the Queensland coast from Brisbane to Cairns, but what was that journey like in the 1930s? Fortunately we have an account of just such a journey. Two men and their wives set out to drive from Sydney to Cairns in a car towing a trailer full of camping gear. The book that resulted from this adventure was Blue coast caravan by Frank Dalby Davison and Brooke Nicholls, published in 1935.

Frank Dalby Davison was in his late 30s when they set off. He had already seen quite a lot of the world, having moved the the USA at 16 with his family and served with the British cavalry in WWI. He spent four tough years farming in southern Queensland with his wife and young family before being driven by drought to retreat to his father's real estate business in Sydney. Frank had several novels to his credit, one of which, Man-shy, the story of a wild red heifer, had won the Australian Literature Society Medal. Frank did most of the writing work on the book.

Dr. E. Brooke Nicholls had trained as a dentist and did original work in dental anatomy but gave up dentistry for natural history writing. He was a pioneering wildlife cinematographer and two of his films, The Living Heart of Australia and Great Barrier Coral Reef were shown commercially in 1923. Nicholls, refered to as 'The Doctor' in the book, was a director of the Melbourne Zoo and a founder of the Gould League of Victoria. He was in his late fifties at the time of the trip and died only a few years afterwards, in 1937. Frank's wife, Kay and Brooke's wife, Barbara play only supporting roles in the book and we don't know what they thought about the adventure.

We will skip over the initial chapters covering the journey through New South Wales towards the Queensland border including an accident caused by a broken trailer axle and delays due to flooding. Sadly for those car enthusiasts who might wish details of the vehicle employed for this adventure, the authors have given us no information at all and there are no illustrations. We join the adventurers as they reach the Queensland border.

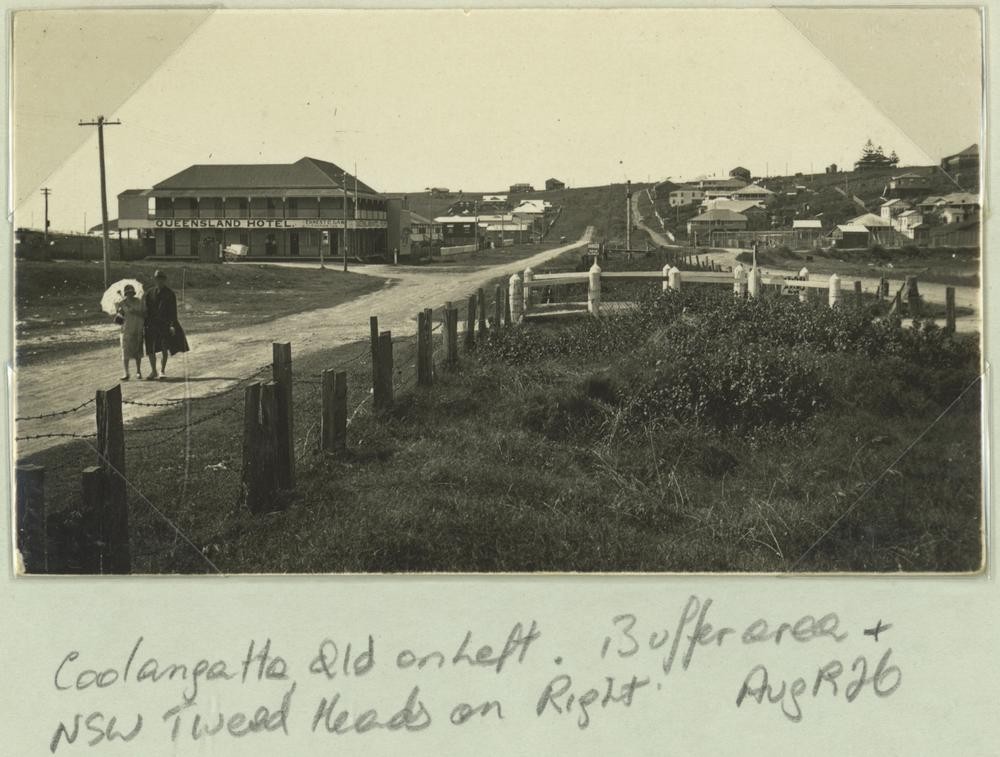

Skirting the hill we came to Tweed Heads. Tweed Heads is, we believe, considered a beauty spot. It may have been ; but humanity has settled there - and that is hard on any place of beauty. There is a scattering of houses whose individual ugliness is relieved - or intensified, according to how one views the matter - by scraps of wooden lace and similar attempts at the adornment of their facades. No doubt there is much natural beauty yet remaining in the vicinity, but to appreciate it the observer would need to occupy a position free from the evidence of human presence.

The crossing of the border is effected by passing through a gateway in a wire fence. We were impressed by the unimpressiveness of our entry in Queensland. We hadn't expected to pass under a series of lofty arches, but a few slack wires and an open gate seemed rather trivial. Why have them? Why have anything? One of us suggested that the purpose of the fence and gate was to keep Queensland cattle-ticks out of New South Wales ; but the rest could not imagine an enterprising tick being held up by a wire fence. At any rate, we gave a hopeful cheer as the car rolled over the bumps between the gate-posts - a proceeding that caused the gate-keeper to eye us askance.

Coolangatta is a wide and wind-ridden town just across the border. It offers no attraction to the traveller and none, as far as we could see, to the permanent resident. It is a watering-place. At first sight the visitor gets the impression that the houses are all two-storied. This is owing to the Queensland custom of building dwellings on stumps six or seven feet high.

It was curious to notice that a political division such as the state border should mark the bounds of a custom in house construction. Approaching the border from the New South Wales side we had not seen half a dozen houses built on tall stumps, but as soon as the boundary was passed, it became the exception to see a house built close to the ground.

The season of our passing was in the last days of May, and people in the town were returning from the beach wearing large straw sun-hats and carrying brightly-coloured beach towels.

You might think that their assessment sounds a bit harsh, but it is typical of their descriptions of towns and houses. They reserve their admiration for the unspoilt natural environment and disparage nearly all the works of man. There are few towns that escape a scathing assessment. The travellers stayed for a week in Brisbane, at Kangaroo Point.

Brisbane proper is a pocket-edition city. Nothing has been left out. It is not abridged, nor, we suspect, from what we observed is it expurgated. In the height of its buildings, the congestion of its foot-paths, its briskness, self-absorption, and sophistication, it is every inch a city. But its inches are not many. Whether you take a conveyance or walk, you are continually surprising yourself by coming to the end of it.

Brisbane generally gets a good report, particularly the trees adorning the city, but we skip most of that and get back on the open road.

Queensland's roads are dreadful. This is not a complaint, merely a statement of fact. The northern State is large and sparsely populated. If the condition of her highways is good enough for her own haulage requirements she is under no obligation to put down concrete for the pleasure of southern motorists.

She doesn't! Brisbane puts a tar macadam highway under the wheels of the north-bound traveller for about thirty miles and then abruptly leaves him to his own devices. From then onward the main coast road is not much more that a bush track in bad condition ; in many places it is a bush track. At long distances apart horse-drawn scrapers are met with, and, at equally long distances, groups of three of four men working with picks and shovels. But the miles are many and the workers are few. The man in ancient legend, whose task it was to push a boulder up a hill as often as it rolled down, had little to do compared with the road repair gangs of Queensland.

On the slopes, the metal, if there is any, is loose and scored by wash-outs. On the level stretches the road is made of stiff mud rutted axle-deep. The ruts are water-logged, and if a vehicle has recently preceded the traveller the sides of the ruts will be coated with slush as slippery as butter. The cautious driver creeps along in second gear, straddling the ruts and praying for his differential case should the car side-slip. The depressions between the hills are pitted with water-filled holes, many of which are shaped exactly to fit a car wheel as high as the hub. In front of these the driver comes to a dead stop, then lowers the car into them. In many places ruts and water-holes exist together, making avoidance by steering an impossibility. Here the driver crawls along at about two miles per hour, his car lurching and rolling like a ship in a storm. Care for the trailer, if there is one, is out of the question ; at best, hopes for its survival may be entertained.

Back-seat passengers are shaken about in a manner that may be good for their health but does not make for their comfort. Although Frank and the Doctor drove with all possible care, Barbara and Kay were not without bruises before the first day's run was over. About seven miles per hour was our average speed. Where we could travel as fast as fifteen miles an hour the drivers blew out their cheeks and revelled in a sense of speed. Occasionally they were able to reach twenty miles , but at that pace they felt as if they were indulging in reckless excess.

Our travellers struggle on over the dreadful roads until they get to Landsborough. From here they plan to venture up the Blackall Ranges where they have an invitation to visit a farm on the road to Maleny.

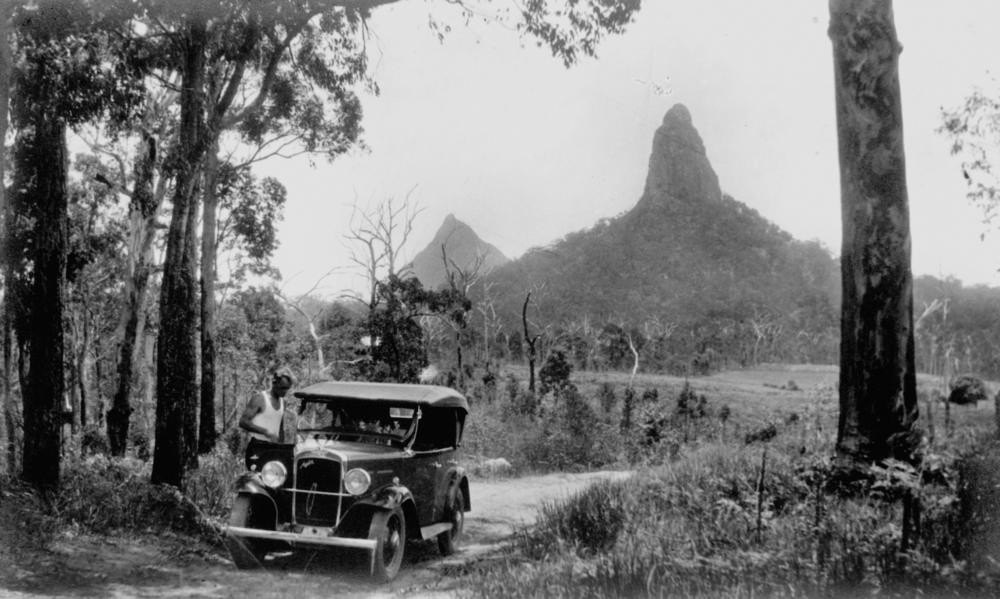

The road up the range was worth the struggle at cost to reach it. Good in itself, its scenic outlook was exceptional. We rose to something approaching two thousand feet, passing from hill to hill along narrow saddlebacks where the road, no wider than a bullock-wagon track, had just room to pass, with steep declivities on either side. To the left we could see far over the low country through which we had come ; and the glasshouse Mountains distinct in the distance. Even far away they lent a character to the land they dominated. Something about that far view stirred the feelings in a way not readily understood, like the notes of a barbaric chant.

The travelling party have an enjoyable stay at the farm of High Tor and appear to find a kindred spirit in its owner Mr Lawrence.

It was interesting to listen to the discourse of one who, clearly, regarded himself not only as the owner, in law, of certain lands, but also as the custodian, in trust, of its beauty. He subscribed to the view that our home must be made habitable. He spoke regretfully of the ruthless slaughter that had been done with the axe. He spoke of developing the latent part of the new beauty that had been revealed - at least within the area given him to control. He talked of the preservation of the last remaining patch of tropic jungle on that part of the range ; and of his efforts to obtain sanctuary for the last of the native birds, who had sought refuge in it.

There are extensive and enthusiastic descriptions of our adventurers' explorations of the rainforest at High Tor but eventually they set off again and come to Maleny.

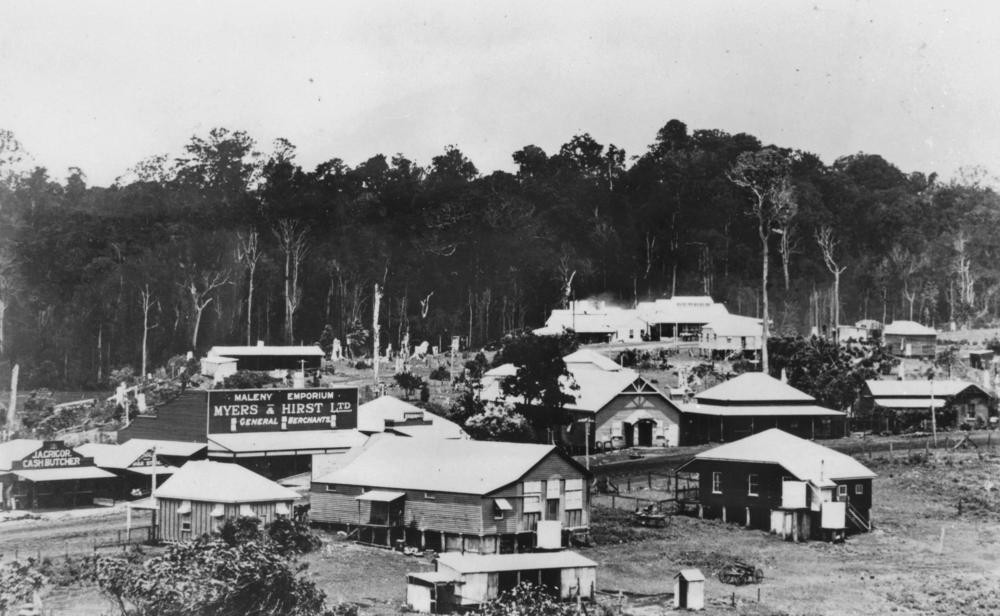

Maleny, where we stopped for petrol, interested us. It made no pretensions to being more than a hardy frontier town. Its main street wandered crookedly up a hill and its bare buildings wandered crokedly beside it. There were no trees, no foot-paths, and, as far as we could see, no building alignment. Yet Maleny rather fascinated us. The blood of commerce flowed richly in its veins. Its stores were jammed full of goods, and each establishment, in its hearty way, pretended by means of a false front, to be a two-story structure. Maleny was too happily busy with the cash-register to bother what it looked like. We were reminded of stories of places where men are men.

From Maleny our travellers descended from the ranges into the Mary Valley.

About us stood brown hill-sides dotted with eucalypts, above them rose the ranges, olive green near at hand, blue in the distance. On the slopes the cattle were feeding knee-deep in the tall grasses, their heads down to the green picking that grew close to the earth. The homesteads were wide apart. There was just the metallic gleam of a roof here and there among the hills. along the winding river grew white gum, brush apple and she-oak. It was our own familiar land and we took a deep breath of it.

The brown of it seemed to rest the eyes. We learned again, as we followed our road through the land's soft folds, what we had learned before, that green is not the only sign and symbol of beauty. With eyes newly opened we saw the beauty of browns and yellows. There was infinite variety of tone : paddocks where the brown lay over beneath the breeze and disclosed a silvery sheen ; squares of yellow that had along their upper surface a tinge of purple given by the ripening seed-heads. Green, when it was seen, was a fine dark carpet underlying the protective top growth ; or in hard-grazed paddock and standing crop it had a richer value by reason of the softer colours that flanked it.

There is little that can be told of the Mary valley, its features are so simple. There are only the ranges, the brown hills, the gums by the roadside, split-rail fences, a homestead or two, and the river, rearranging their groupings as we advanced toward them. Hour after hour, at a comfortable pace, we moved into that picture, and hour after hour it changed before our eyes. Always there were the same components ; always the picture was different.

The travellers made their way to Maryborough and from there by boat to spend several weeks on Fraser Island. On their return to Maryborough they decided to abandon the idea of travelling all the way to Cairns by car. The roads were bad and there were still 800 miles to travel so they went by train. The adventure continued in and around Cairns and on the Great Barrier Reef but we will leave them here with the abandoned car and trailer.

Simon Miller – Library Technician, State Library of Queensland

Comments

Your email address will not be published.

We welcome relevant, respectful comments.