From Across the Seas: Tracing Australian South Sea Islanders

By Christina Ealing-Godbold, Research Librarian, Library and Client Services | 19 August 2022

While contributing greatly to the economy of both Queensland and New South Wales, the indentured labourers of the Pacific Islands and their descendants lived as a minority group throughout the 20th century, denied the rights of formal recognition and restricted by a range of Government legislation. Discovering their stories and finding the details of their journeys will add to our understanding of our history and of the contribution the hard-working island people made to developing Australia.

Uncovering the stories of a minority group – Australian South Sea Islanders.

About 62,000 South Sea Islanders were recruited for the labour trade in Queensland between 1863 -1903. Islanders were taken from more than 80 pacific islands, although those in Queensland were mostly taken from the Islands of Melanesia, particularly from Vanuatu.

South Sea Islanders arrive by ship in Bundaberg 1895. John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland. Negative number: 18058.

Australian South Sea Islanders planting sugar cane on a plantation at Bingera, Queensland, ca. 1897. In APO-32 Queensland Views Photograph Album, John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland. Negative number: 142351.

Many South Sea Islanders were repatriated upon Federation, but at least 1,600 stayed legally in Queensland, and another 1,000 melted into society. Now, it is thought that there are more than 20,000 descendants of South Sea Islanders in Queensland.

Dates and history of the Queensland Labour Trade.

The first ship to bring South Sea Islanders to Queensland was the Don Juan in 1863, and the 67 young men ‘recruited’ were primarily from the Island of Tanna in the New Hebrides (now called Vanuatu). At first, the islanders were recruited for the cotton plantations by Robert Towns, but sugar cane soon became more profitable.

South Sea Islander cane workers on a plantation in North Queensland, ca. 1868. John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland.

Queensland was not the only place in the world wanting labourers to work at plantations, and labour recruiting vessels scoured the islands from France and the Americas, looking for healthy young men. The evidence from all accounts indicates there was a great deal of barbaric and inhumane treatment in the recruiting or taking of the labourers and many church men and reformists demanded that the “slave trade” be regulated.

After 1868, a range of legislative instruments passed through the Queensland Parliament, each one attempting to bring the labour trade under control, with rules about food, housing, wages and medical treatment. However, the significance of the legislation is found more in the degree to which it failed to regulate or prevent the abuses, rather than in its success.

There was a break in the trade between 1890 and 1892. However, Queensland planters begged for labourers, and it was agreed by the Premier that the trade would then continue for another ten years.

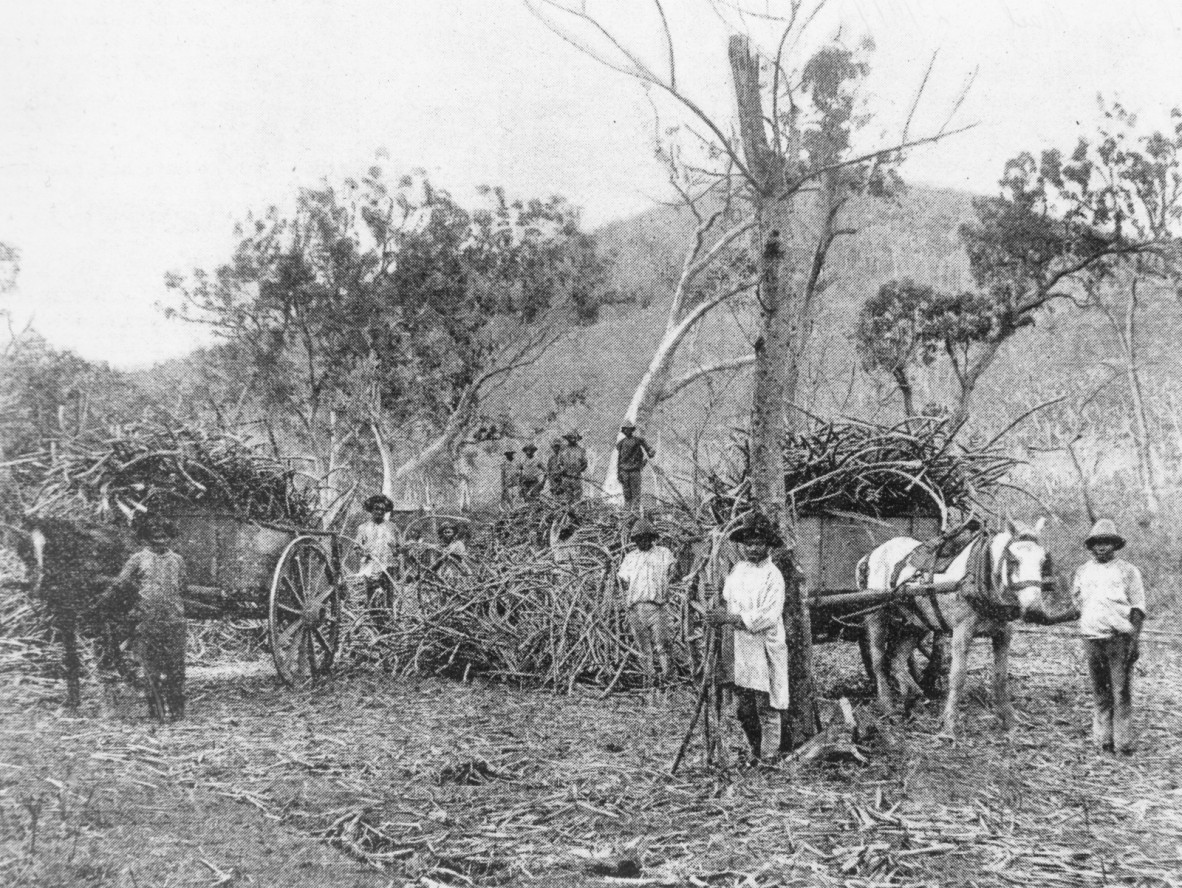

Australian South Sea Islanders with wagons loaded with sugar cane in Mackay, Queensland, 1895. John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland. Negative number: 9259

In 1901, the new Australian Federal Government decreed that all islanders had to be repatriated (or deported) to their homes. Most were repatriated by 1908. However, for men who had been living in Queensland for many years, with families and connections here, the prospect of returning to an island where many of their family had become estranged from them did not fill them with enthusiasm. There were even cases of labour ships returning labourers to the wrong island. There were numerous protests against this deportation.

There were some exemptions from deportation- for those who had arrived in Queensland prior to 1879 or had married a person who was not a South Sea Islander or for those who had bought freehold property. About 1600 people were exempted legally, while another 1,000 or more could not be accounted for and had made themselves invisible in Queensland society. Some made the journey to New South Wales to the Chinderah and Tweed River area so as not to be at the mercy of Queensland legislation.

Where to find records

Discovering the stories of Australian South Sea Islanders has many challenging aspects, including the fact that their Island names were changed and prefixed with English names such as Moses and Charlie. Sometimes the surname was replaced with the name of their home Island (e.g. Tanna or Aoba), and other times by the name of the ship they had been recruited to join. Among the names there are many beginning with “T” and ending with “o” or “ow” or “ou”. Plantation overseers also gave names to the young men by which they became known. Finding their names in the records is therefore often fraught with difficulty.

Formal records were poorly kept in the 1860s and indeed, after the Polynesian Labourers Acts of 1868, and its many amended versions throughout the 1870s, there was still a great deal of poor recording aboard the labour ships. The appointment of Government Agents to sail on each ship after 1870 did little to improve the situation, as they were at the mercy of the ship captains. Yet the agents did make attempts to list the recruits as they arrived and indicate the terms of their employment, where they landed and write the name given.

The John Oxley Library at State Library of Queensland has a number of diaries written by ship Captains and labour traders, including the following diaries:

- OM71-04 William Hamilton diary

This is the log book/diary kept by William Hamilton relating to the activities of the Hamilton Pearling Company in New Guinea and the Solomon Islands collecting turtle shell, pearl shell and trepang, and the clearing of land for plantations.

- OM76-04 Sydney Mercer-Smith Diaries 1892-1900

The diaries relate to the author's service as Government Agent on board the Labour Vessels, 26 January 1893 - 9 July 1900. There is also 1 pamphlet - "Imperial and Colonial Acts relating to the Recruiting, Etc., of Pacific Island Labourers, and Regulations made thereunder". Brisbane, 1892.

There are also many photographs of Australian South Sea Islanders, accessible through State Library’s online catalogue, One Search. Association records (Mackay Sugar Planters Association) and business records of mills (Fairymead in Bundaberg) can also provide interesting information about the Pacific Islanders in their employ.

Queensland State Archives (QSA) is a great source for finding records of individuals, as they have more than 112 separate registers or record sets with details of Pacific Islanders. The following QSA indexes can be accessed and downloaded via the Qld Government Open Data Portal:

- Australian South Sea Islanders 1867-1948

- Coloured labour and asiatic aliens in Queensland 1913

- Sugar Exemptions 1922-1923

An Inspector of Pacific Islanders was located in each of the major sugar regions in Queensland, including Bundaberg, Maryborough, Childers, Mackay and Townsville and each Inspector kept registers and lists of islanders working in their districts. State Library of Queensland has a microfiche copy of this index, accessible on Level 3.

The Pacific Manuscripts Bureau at ANU has its own website and online catalogue, and there are many records of plantations and companies in the Pacific that have been added to their collections.

There are also some records of business and religious organizations in the Pacific in the Miscellaneous series of the Australian Joint Copying Project (AJCP).This resource is available digitally, provided by National Library of Australia.

Finally, many of the Australian South Sea Islanders were Christianised. In many locations of Queensland, they had their own mission churches and Sunday Schools. In fact, many of the labourers and their families learnt to read and write in the mission Sunday schools. The mission churches were protestant and aligned themselves with the Anglican church, the Uniting Church (Presbyterian and Methodist) and also the Assembly of God and Seventh Day Adventist churches. The history of churches such as St John’s in North Rockhampton are useful for locating family names and connections. There was also a mission church at Fairymead in Bundaberg, and another in Mackay.

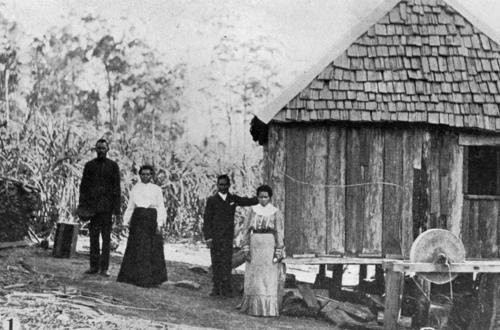

South Sea Islanders at Diddillibah, Queensland in 1906. John Oxley Library, State Library of Qld. Negative number: 23815.

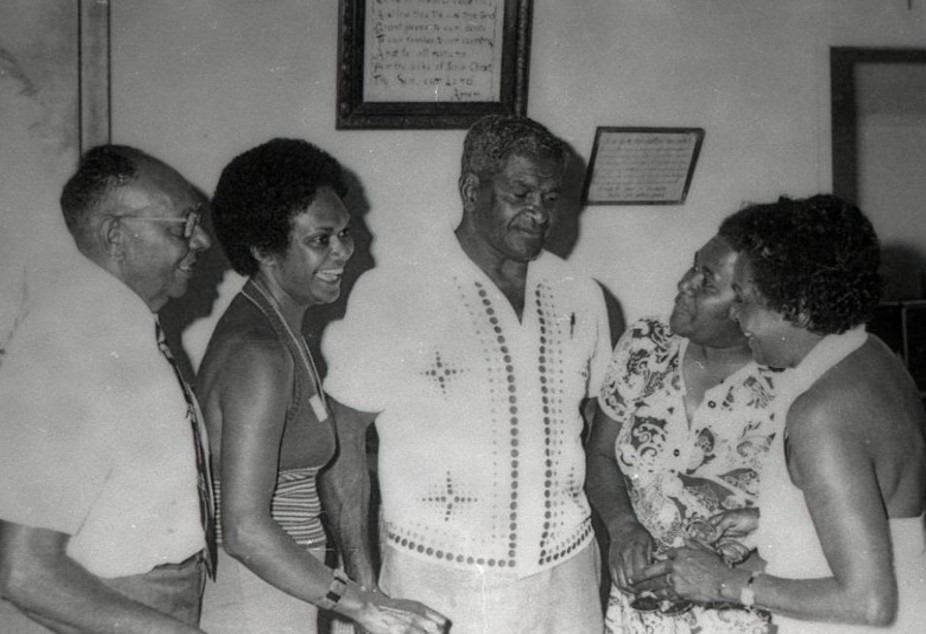

Australian South Sea Islanders formed their first political organization in the Tweed River area in 1975. Over the coming decades a number of organizations would be formed to fight for the rights of the islanders with regard to recognition and benefits. Records held in the John Oxley Library include

- Australian South Sea Islanders United Council Records 1975-2008

- 29744 Australian South Sea Islanders 150 Commemoration and Festival 2013 Papers 2013

The records from these organizations have been donated and organized by Ms Nasuven Enares, daughter of an indentured South Sea Islander and a leader in Australian South Sea Islander organizations.

Zane Corowa, Nasuven Enares, Wally Mussing, Naru Leichhardt and Faith Bandler. Circa 1950. Photograph courtesy of Tweed Regional Museum.

Nasuven Enares’ story

Nasuven’s own family history provides an interesting window into the lives of a South Sea Islander family. Her father, Moses Toupay Enares, from the island of Tanna was taken forcibly from the beach near his home when aged about 12 or 14 years. He travelled, imprisoned in the hold of a ship &fed on poor food, and arrived in the Bundaberg or Maryborough area where he was assigned to a particularly harsh master. After some years, he and some fellow labourers heard about a more generous master called John Robb, working a sugar mill at Cudgen, just over the Queensland border.

In New South Wales, the labourers were not subject to restrictive Queensland legislation. Travelling undercover at night by hiding on sugar cane railway wagons, Toupay and his friends made their way to Cudgen where he became a very successful banana farmer Moses Toupay married Emily May Sendy, a second-generation South Sea Islander and they became respected members of the Murwullimbah and Tweed River communities, and had 11 children, Nasuven being the youngest girl.

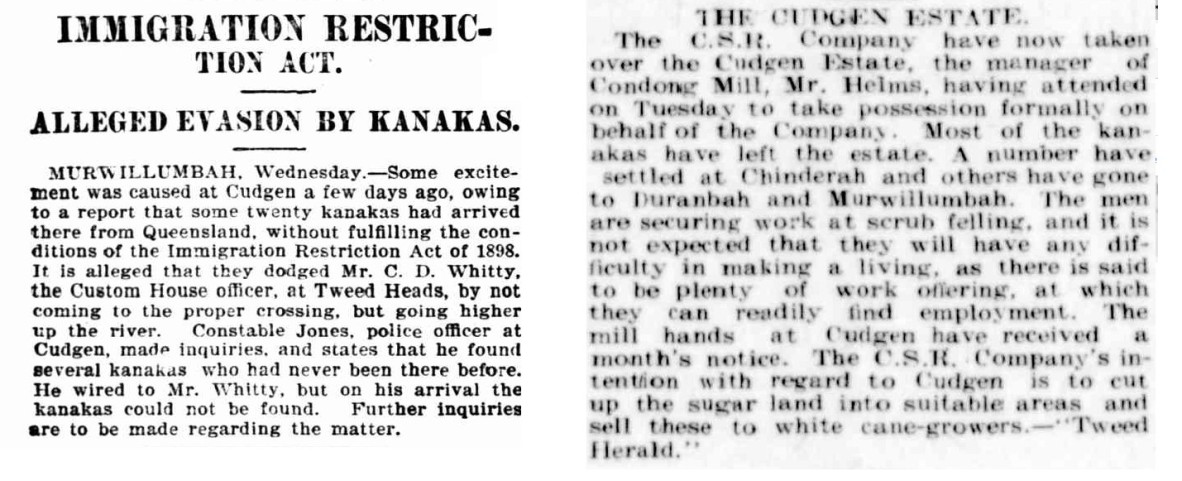

Unfortunately, Moses is not listed on any of the shipping registers by any of his cultural names. The names under which he may have been recorded vary from Tavo to Toupay or Toopay or Tooway to Taenares or Taernarese so it is uncertain upon which ship he travelled to Queensland. There were a number of recruits named as Moses, but none appear to be Toupay Enares. However, his age (probably born around 1878) would indicate that it was probably in the extension period, between 1892 and 1902 that he was recruited. Moses moved to banana farming, as the sugar lands at Cudgen were to be sold to white farmers only after the 1912 take-over by Colonial Sugar Refinery.

Moses died in the early 1960s, reportedly at more than 80 years of age. His journey to New South Wales may have been to escape the impending deportation as he would not have been entitled to an exemption under the new Federal legislation. Generally, South Sea Islanders that had been here prior to 1880 were allowed to remain.

This article in the newspaper in 1900 may well refer to Moses Toupay Enares.

Left - Alleged Evasion by Kanakas. Evening News, Thursday 25 January 1900, page 8.

Right - The Cudgen Estate. Northern Star, Sat 23 Mar 1912 Page 4.

Recognition for South Sea Islanders

On the 25th of August 1994, the Australian Government formally recognized the South Sea Islanders as a distinct cultural group. Prime Minister Paul Keating recognized the Australia South Sea Islander (ASSI) group, and this was followed by recognition in New South Wales in 1955, and in Queensland by Premier Peter Beatie in the year 2000.

On the 25th of August every year we recognise our Australian South Sea Islanders (ASSI) community as part of our national cultural calendar.

Selected further reading

- Quite a colony: South Sea Islanders in Central Queensland, 1867-1993

- Sea Memories: Life of Captain John Mackay Robert Staib (great grandson)

- Across the Coral Sea: Loyalty Islanders in Queensland = Embarquement pour le Queensland: des Loyaltiens en terre australienne

- 29744 Australian South Sea Islanders 150 Commemoration and Festival 2013 Papers 2013

- 4834 Ross Johnston's manuscripts on William Hamilton

More information

Family History Month - /familyhistorymonth

Family history - /research-collections/family-history

Ask us - /plan-my-visit/services/ask-us

Library membership - /get-involved/become-member

Comments

Your email address will not be published.

We welcome relevant, respectful comments.