Your loving Aussie, Charlie: Part Two

By Alice Rawkins, Engagement Officer Anzac Square Memorial Galleries | 20 February 2025

‘They were the cream of our youth, they died bravely, but they died young.’

This is part two of a blog on Charles (Charlie) Rowland Williams, an Australian airman who served with the RAF during World War II and was involved in the infamous Dambuster Raid in May 1943. To fully appreciate Charlie’s unique wartime service, it is recommended that you read part one first.

A studio portrait of Charles Rowland Williams taken on completion of his RAAF training in Australia.

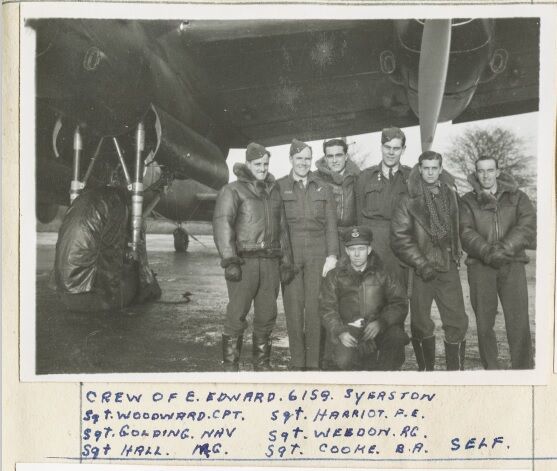

In late July 1942, Charlie Williams was attached to No. 61 Squadron following the successful completion of his training at Cottesmore. After more than one year of training he was keen to finally start his first operational tour, which would consist of thirty operational flights not exceeding 200 hours. He was also excited that No. 61 Squadron flew the new Lancaster bombers, writing home ‘last night I had my first trip in the new machines and enjoyed the trip, they are great to fly in and so much faster than the ones I have been use to’ (22 Jul 1942). In late August he was ‘crewed up’ assigned as the Wireless Officer to a seven-man team, which would operate a Lancaster (31 Aug 1942). Charlie’s crew consisted of himself, one Canadian and five British Airmen, who after a short conversion course were finally ready for action.

Crew of E. Edward 61 Squadron Syerston, 1942. Charlie is kneeling in this image.

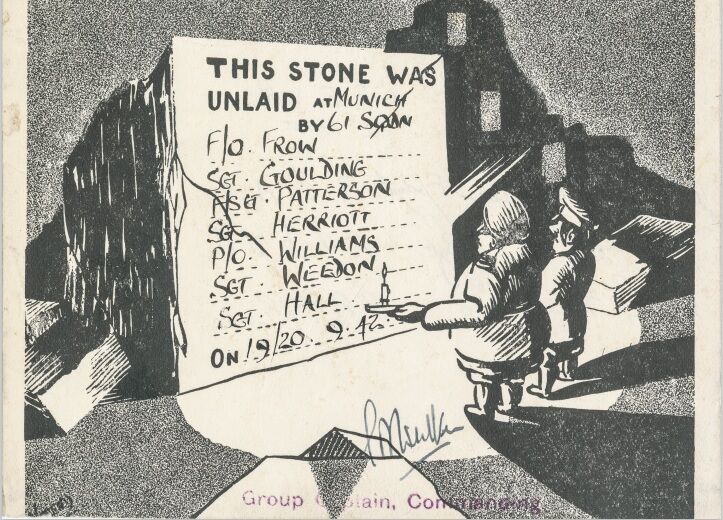

Charlie’s first operational mission was on 19 September 1942, with a highly successful bombing raid on Munich. To mark the occasion, Charlie obtained a standard Air Force postcard, had it signed by his commanding officers and crew and pasted it in his logbook. The inscription read ‘this stone was unlaid at Munich by 61 Squadron on 19/20.9.42’ alongside the name of the crew. They flew another 7 raids before their pilot Flying Officer Frow finished his operational tour, including night raids on the Baltic coast, Wismar, Kiel and a daring daylight raid on the Schneider armament factory near Le Creusot. In November 1942, Frow was replaced by New Zealand Flight Sergeant Ian Woodward, who initially experienced some difficulties learning to land the Lancasters. In a letter to his family in mid-December, Charlie off handily mentioned that his new pilot’s training was taking longer than anticipated due to a ‘small accident’, which had occurred when Flight Sergeant Woodward struck another Lancaster aircraft while trying to land his own aircraft. In Charlie’s next letter he reassures his family that ‘my pilot has “come good” and is having no further trouble with the landings’ (13 Dec 1942). With Woodward’s training complete the crew returned to operations in January 1943, completing raids on Hamburg, Cologne, Lorient, Turin, St Nazaire and Wilhelmshaven.

Postcard celebrating the raid on Munich in Charles Rowlands Williams RAF logbook.

As Charlie settled into life with No. 61 Squadron, he began to socialise more and form new relationships. He was invited to numerous parties and welcomed into the homes of residents. This allowed him to banish painful thoughts of his Australian fiancé Millie, who he had not received word from in several months. His squadron, based at Syerston, was only a short journey from Nottingham, the region's major city. It was here that he met Gwendoline (Bobbie) Parfitt, a secretary at the Navy, Army, and Airforce Institue (NAAF). The couple started as friends, attending the same social events, frequenting a local bar, The Hag, together and exchanging reading recommendations. Love quickly bloomed between the couple and Charlie began regularly writing to Bobbie, signing off ‘Your loving Aussie’. This new relationship had a small setback in November 1942, when Millie unexpectedly began writing to Charlie again claiming that she had never received any letters from him. By this point Millie herself had joined the Women’s Auxiliary Australian Air Force in Australia. Charlie was in a difficult position, but decided to continue his relationship with Bobbie, who had been the one to mend his broken heart and support him through his first operational tour. He would later explain to his family that:

’I do not believe that she [Millie] wrote every week as she said she did or there would not have been a lapse of six months without letters or even cables, even now I think there was something peculiar going on’.

Charlie and Bobbie’s relationship quickly flourished, with the couple spending all their leave together. By April 1943 they were engaged and planning a life together, with Charlie writing to Bobbie:

‘It will be very nice to wake up and find you still there, and there will be no need to find dark corners to kiss you and make love to you, we will be able to do just what we want’.

Charlie dreamed of finding them a little place where they could enjoy their leave together instead of always rushing to drop her back at the girls' billets before curfew. He was an affectionate writer, taking pains to reassure Bobbie of his devotion; ‘Every time I see you I seem to miss you more when I leave you, and look forward to our next meeting’ (17 Apr 1943). In several letters he also encourages her not to worry about the ‘other one’, a reference to his broken engagement with Millie. Charlie initially kept this new relationship secret from his family, possibly to avoid a difficult conversation around perceived disloyalty to Millie. Tragically, they would not find out that he was engaged to Bobbie until after his death.

Portrait of Gwendoline (Bobbie) Parfitt in Charles Rowland Williams's wartime scrapbook.

In March 1943, Charlie’s first operational tour was drawing to a close, having completed 22 trips and 148 hours. He writes to his family that he ‘will not be sorry to finish and have a rest as the strain is beginning to tell’ (1 Mar 1943). As an airman he had become accustomed to danger and loss, with the death rate for bomber command 44.4%. Charlie knew the odds were not in his favour and had lost numerous friends to active missions and training exercises. Disaster could strike at any moment, with Charlie’s crew experiencing a close call on 8 March:

‘On Thursday night we went to Nuremburg which is a long way into enemy territory but we had quite a good trip but had a bit of a dust up returning over the French coast but were not hit but really shaken, the worse part of the trip was just before we landed, the trip took us much longer than it should have, and we were short on petrol and when we landed we only had four minutes of petrol left, however the luck held and we got down O.K. but at one stage we all had visions of bailing out’.

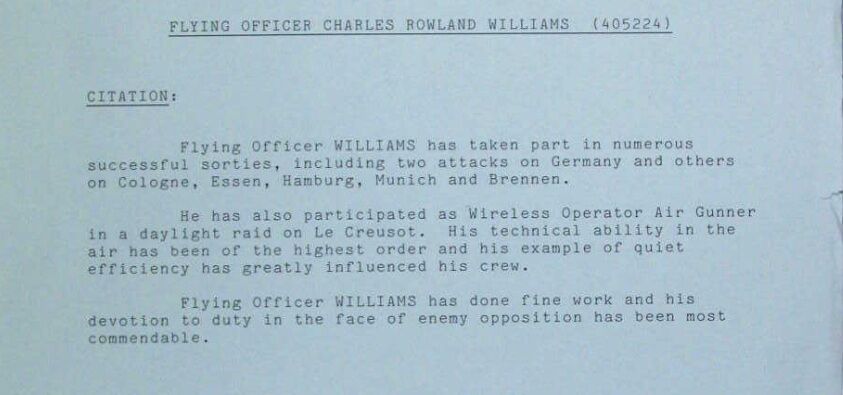

Charlie finished his first operational tour on 27 March with a successful bombing raid on Berlin. He was recommended for a Distinguished Flying Cross (DFC) for his ‘technical ability in the air’ and ‘his devotion to duty in the face of enemy opposition’.

Charles Rowland Williams Distinguished Flying Cross citation

During World War II when RAF airmen finished their first tour, they were generally given a six-month break, usually spent as instructors with training units, followed by a final operational tour. Despite being exhausted, Charlie was keen to return home after receiving news that his father's health was deteriorating rapidly. It was this reason, combined with homesickness, that led him to decide against delaying his second operational tour. Instead, he explained to his family:

‘Yesterday I made a decision which may or may not be wise, I am joining a crew with an Australian pilot, he, like myself has nearly finished his first tour and when we have finished we are going to another squadron and will carry on with our second tour without rest, the second tour now consists of 20 trips and we believe when we have finished our operation we will have a much better chance of being sent home’.

It was this decision that sealed Charlie’s fate. The Australian pilot Charlie referred to was Norman Barlow, who he would serve and die alongside during the fateful Dambuster Raids.

Studio portrait of Charles Rowland Williams in his wartime scrapbook.

Charlie was selected to join No. 617 Squadron in March 1943, a special and top-secret unit formed in Scampton to bomb three dams in Germany’s industrial heartland, the Ruhr Valley. Codenamed Operation Chastise, it was thought that the destruction of these dams would cause massive disruption to the German war production industry, with dams flooding several key steel and weapons factories, ultimately weakening Germany’s position in the war. To complete the mission, the squadron would use Barnes Wallis’s newly designed “bouncing bombs’, which when dropped correctly would bounce across the surface of the water until they hit the dam wall. The bombs would then sink, and a hydrostatic fuse would detonate the mine at a depth of 9.1 metres, hopefully breaching the dam wall.

No. 617 Squadron practise dropping the 'Upkeep' weapon at Reculver bombing range, Kent, 1943.

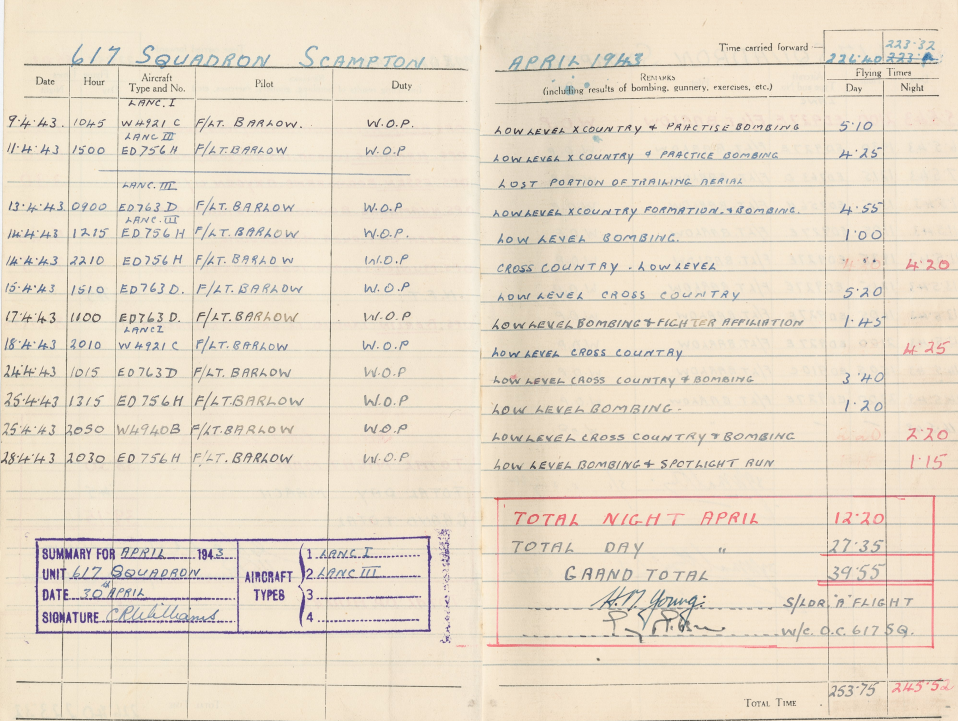

As a highly skilled and well-respected Wireless Officer, Charlie was a perfect candidate for this dangerous mission. He settled into his new posting quickly, joining a crew of seven other men, including Barlow. His only disappointment was that Scampton was 50 kilometres from Nottingham, preventing him from easily visiting his sweetheart Bobbie. The squadron had just eight weeks across April and May 1943 to prepare for the mission and began intensive daily training in the modified Lancaster bombers, practicing low level night flying and navigation, over bodies of water and canal systems and crisscrossing the country, including Scotland. Dummy bombs were dropped at a height of 18 metres on several different reservoirs. Low flying in bomber aircrafts was extremely dangerous, especially in the heavy and cumbersome Lancasters. On their second practice flight, Charlie recorded in his logbook that they had ‘lost portion of trailing aerial’, which had been ripped off possibly by a tree (11 Apr 1943). On another occasion he wrote to Bobbie:

‘I forgot to tell you that when we were flying on Friday we were down fairly low and we ran into a flock of birds, some of which came through the wind-screen of the plane and caused the pilot to lose control of the plane for a few seconds and we hit the top of a tree but it did not do any damage, and we were able to continue on our journey’.

To ensure the secrecy of the mission none of the airmen involved were given a reason for these operations. Charlie cautioned Bobbie that ‘you must not ask me questions about the station’ as he wouldn’t be able to tell her anything (8 Apr 1943).

Training exercises completed by Charles Rowland Williams in April 1943. Information recorded in his W/T Operators Flying log book.

With the intensive training No. 617 Squadron was completing, Charlie found it hard to get leave to see Bobbie. He missed her fiercely, writing to her each day they were apart and calling her when possible. At the end of April, he secured permits for them to marry and organised to meet her family, who were apprehensive about their impending nuptials. He jokingly wrote to Bobbie ‘I am looking forward to seeing you on Saturday, but I am not looking forward to the commencement of hostilities, but I expect to stand up to the barrage alright’ (29 Apr 1943). After a rocky start, he managed to secure her family's approval. He also wrote home in early May to inform his family that he had broken his engagement with Millie and now planned to bring an ‘English wife back to Australia’ (8 May 1943). For Charlie and Bobbie these were the final moments of happiness before disaster struck.

On Friday 14 May, Charlie and his crew were informed that zero hour for Operation Chastise was close, although they still did not know the targets. The following day he penned a final letter to his family reassuring them that his pilot was ‘very good’ and that ‘I have every confidence that he will bring me through my second tour’. Due to security concerns, he was unable to share any information pertaining to the upcoming raid, simply writing:

‘How I wish I could tell you everything I would like to, there is so much I could tell you but until the war is over I cannot tell anyone but I hope in the near future I will be able to tell you some of the amazing things I have seen and experienced’.

He made a last-minute dash into Nottingham on Saturday evening, desperately hoping to catch Bobbie before she headed home. Sadly, their paths did not cross, and he returned to his station disheartened. Before embarking on what would be his last flight on 16 May, Charlie sent Bobbie a brief letter. He apologised for not being able to visit her over the last few weeks and hopes to explain everything when he returns. He is optimistic that following this raid he will be able to get leave so they can be married. He signs off one final time, ‘All my love dear and kisses, Charles’.

The story of the Dambuster Raids has been told many times, and it remains one of the most daring operations undertaken by Bomber Command during World War II. The squadron was divided into 3 waves, with the first to attack Mohne Dam, the second including Charlie’s crew, the Sorpe Dam and the final to fly in reserve ready to attack as directed. Charlie’s Lancaster AJ-E, piloted by Barlow took off at 9:28 pm. At 11:50 pm, after crossing the Dutch German border near Haldern, AJ-E struck an electrical pylon, causing the aircraft to crash. All aboard were killed. This was the risk that came with low altitude flying combined with poor night visibility. The furiously burning aircraft came to rest in a small meadow and was the first of two Lancasters to hit powerlines during this raid. The bomb was thrown clear of the crash and was later examined by Luftwaffe intelligence.The severely burned bodies of the crew were taken to Dusseldorf North Cemetery and after the war were reburied in Reichswald Forest CWGC War Cemetery. AJ-E was one of eight aircraft (out of nineteen) that failed to return that night.

While Operation Chastise resulted in the successful breach of Mohne and Eder Dam, and partial destruction of Sorpe Dam, the cost was high. It is estimated that 1,300 civilians and enslaved labourers from the Soviet Union were killed due to flooding. The impact on Germany’s wartime industry was also limited, however, it did provide a significant boost to morale for the people of Britian. The casualties for the RAF were appalling, with 53 of the 133 aircrew who participated killed during the attack, a casualty rate of almost 40%.

Flying officer C.R. Williams DFC RAAF grave at Reichswald Forest CWGC War Cemetery.

Charlie’s death came as a tragic blow for his family, with his father passing away just a few days later. News of his broken engagement had also not yet reached Australia, so Millie McGuiness was notified by authorities that his aircraft was ‘missing without trace’. She at this stage was engaged to an American Servicemen, Ronald Marvin Johnsen, whom she married a few weeks after the Dambuster Raids. It was left to Bobbie to set the record straight, and in August she was officially notified that Charlie was ‘Missing, believed killed in action’. His death was officially confirmed in October 1943, after months of his fiancé and family desperately hoping that he had been taken as a prisoner-of-war. His mother Hedwig would later write to Bobbie that it seemed so unfair that the young couple had been robbed of their happiness so close to their wedding. In a photo album that Charlie was compiling before his death Bobbie would inscribe:

‘Flying Officer CR Williams DFC and Bar, who had asked me to become his wife … to the end of my life I shall never forget’.

We are honored to have this photo album and Charlie’s wartime correspondence and logbook in our collections at State Library. These items tell a powerful story of a brave young Australian airman who was dedicated to ‘the fight for everlasting peace’ (26 May 1942). Moreover, this collection provides a deeply personal insight into a love story between Charlie and Bobbie, who were brought together and separated by the horrors of World War II. This Anzac Day we remember Charles Rowland Williams and share his legacy as one of only thirteen Australian Dambusters.

Lest we forget.

References:

-

An Airman far way: The story of an Australian Dambuster by Eric Fry

Comments

Your email address will not be published.

We welcome relevant, respectful comments.