Your loving Aussie, Charlie: Part One

By Alice Rawkins, Engagement Officer, Anzac Square Memorial Galleries | 20 February 2025

On the night of 16 May 1943 Flight Officer Charles “Charlie” Rowland Williams, a Queensland wireless operator with the RAF, penned a quick letter to his British fiancé Bobbie before embarking on the fateful Dambuster Raid targeting Sorpe Dam in Germany. In this letter he promised to visit her soon and signed off ‘Cheerio for now darling and believe me when I say I love you very dearly and always will’. They had planned to get married the following week. After a courtship of stolen moments whenever Charlie could get leave, the couple were eager to start their lives together. Sadly, Charlie, who was just a few short flights off finishing his second operational tour was one of 53 Allied airmen killed during the Dambuster Raids. This Anzac Day we are honoured to share Charlie’s story of service.

A studio portrait of Charles Rowland Williams taken on completion of his RAAF training in Australia.

Charlie’s wartime collection, which includes heartbreaking letters to his fiancée and material lovingly kept by his Australian family, now resides at State Library and has been largely digitised. This remarkable collection provides a deeply personal insight into the dangers faced by Air Force personnel during World War II and how this impacted their relationships. Deeply woven into Charlie's wartime story are elements of bravery, loneliness, loyalty, second chance romance, duty and loss. While exploring this collection it quickly became clear that this was not only a tale of heroism, but of a great love between a couple brought together by war. In this two-part blog we use Charlie’s letters to dive into his World War II service as a graduate of the Empire Air Training Scheme (EATS) and wireless operator for No. 61 Squadron and later No. 617 Squadron.

Charles Rowland Williams, better known as Charlie, was born in 1909 at Townsville Queensland to Horace Williams and Hedwig Helene Catherine Hampe. He was the middle child, with an older brother Doug and a younger sister Shelia. The family moved several times during Charlie’s childhood with his father managing a series of sheep stations before they settled at Telemon, a station near Hughenden, when he was 10 years old. He was an active child and loved to play cricket and tennis with his father and siblings. From an early age he was taught to ride, shoot and help with the farm work. The boys were initially tutored at home by their mother, who had worked as a governess before her marriage. When they were older, they attended Townsville Grammar school as boarders. Charlie left school at 16 years old and returned to work at Telemon station with his father and brother. He became a skilled mechanic and began building wireless sets, which helped connect the Telemon radio stations. In his spare time, he was a passionate photographer, a hobby that he would later use to document his wartime service. While he enjoyed the outdoor lifestyle of farming, he dreamed of becoming a pilot and applied to join the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) when he left school. His application was not successful, possibly due to his limited education. Undeterred, he would later take flying lessons at the aero club in Townsville.

Shelia Williams, overseer, Charlie, Doug and Horace Williams posing for a photo after a game of tennis at Telemon.

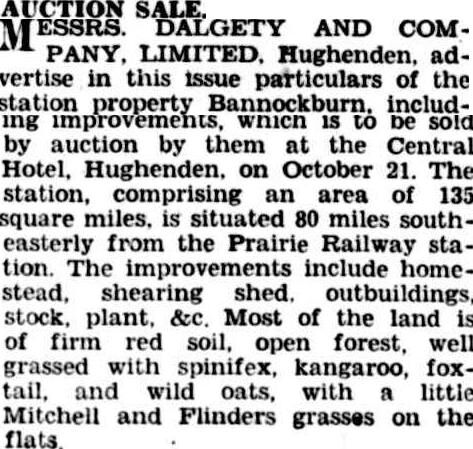

The Great Depression in the early 30s was a particularly tough time for the Williams family. Telemon was sold due to the collapsing price of wool and the new owners were not willing to keep Horace on as manager. The situation was far from ideal, with Horace, who was 69 years old and experiencing health issues, no longer able to consider retirement. Instead, in 1933, he and two friends formed a syndicate to purchase Bannockburn station, near Torrens Creek. This station, located in desert country, was so isolated that they only received mail once a week and their nearest neighbour was over 20 kilometres away. When the family arrived, they made the unhappy discovery that the cheerless homestead was also overrun by brown snakes. The family decided to run sheep for wool and worked hard to build up the farm, but with only one farmhand, most of the work fell on Charlie and Doug. Bannockburn station would require many years of sacrifice and improvements before their finances stabilised in 1937.

Newspaper article on the auction sale of Bannockburn station in 1933.

When war was declared in 1939 the Williams siblings were eager to contribute. Charlie and his brother could have avoided military service due to their father’s failing health and his inability to run the property by himself. However, with the farm now making a profit they could afford to hire more help, allowing the boys to join the war effort. It was decided that Doug would enlist in the Army Reserve and remain in Australia, allowing Charlie to follow his dream and apply for the Air Force. While waiting to be called up by the RAAF, Charlie joined the 26th Battalion, a militia unit based in Townsville. This was the same unit that Doug would serve with until 1943. Meanwhile, Sheila took on a greater role at Bannockburn, learning to fix the cars and helping to ensure the station continued to flourish.

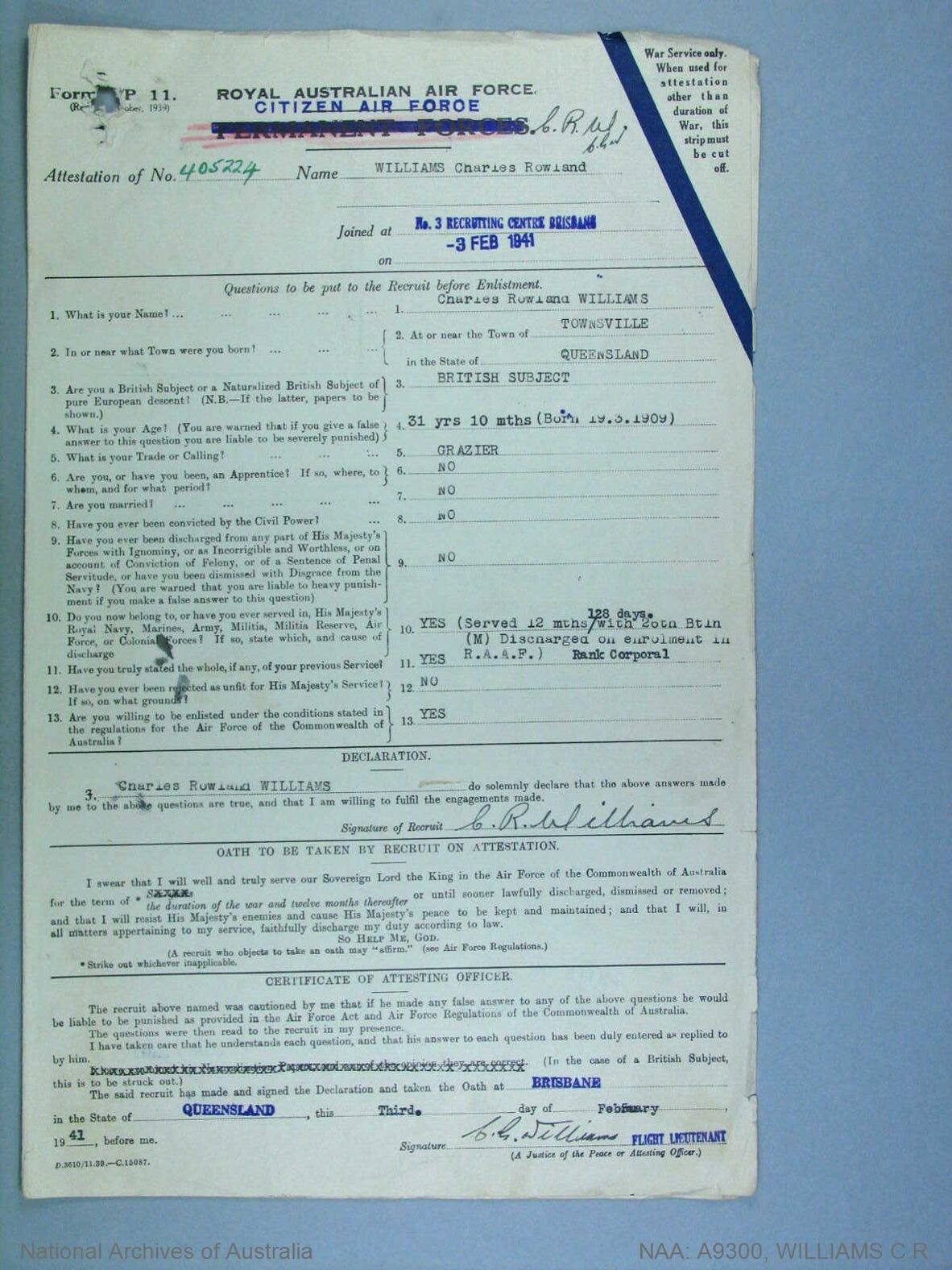

Charles Rowland Williams World War Two Service Records

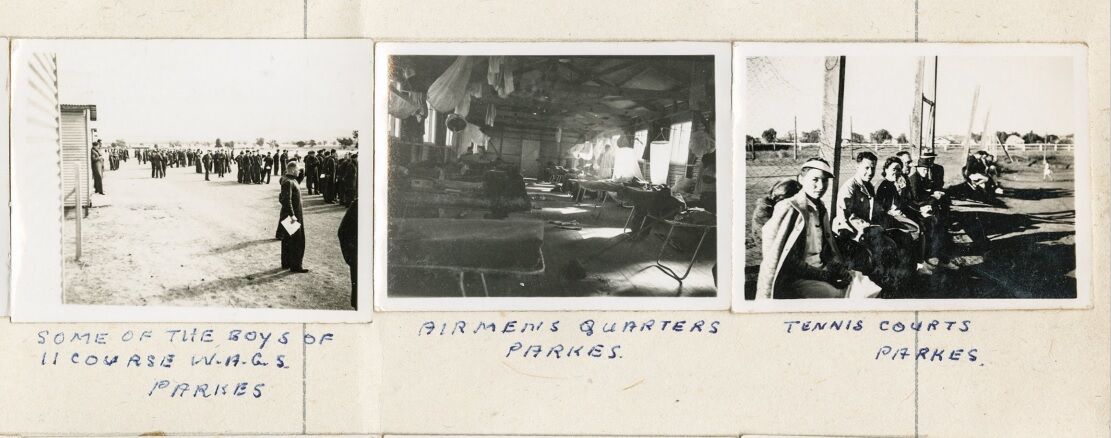

In August 1940, Charlie was finally summoned for his Air Force interview and medical assessment, which he easily passed. He was discharged from the Army on 3 February 1941 after almost a year with the 26th Battalion and ordered to report to the RAAF Recruiting Centre in Brisbane. At almost 32 years old, he was considered too old for pilot training, despite his actual flying experience. He was bitterly disappointed. Instead, he was mustered as a wireless operator/air gunner. He completed the majority of his training in RAAF stations in rural New South Wales, including No. 2 Wireless Air Gunnery School located at RAAF Station Parkes. This station was part of the newly formed Empire Air Training Scheme (EATS), a program designed to train RAAF airmen for eventual transfer into the RAF during World War II. The training here was rigorous and of the 80 airmen who started the wireless air gunner course with Charlie only 49 passed their examination.

Photos taken by Charles Rowland Williams while stationed in 1941 at No. 2 Wireless Air Gunnery School located at RAAF Station Parkes, New South Wales.

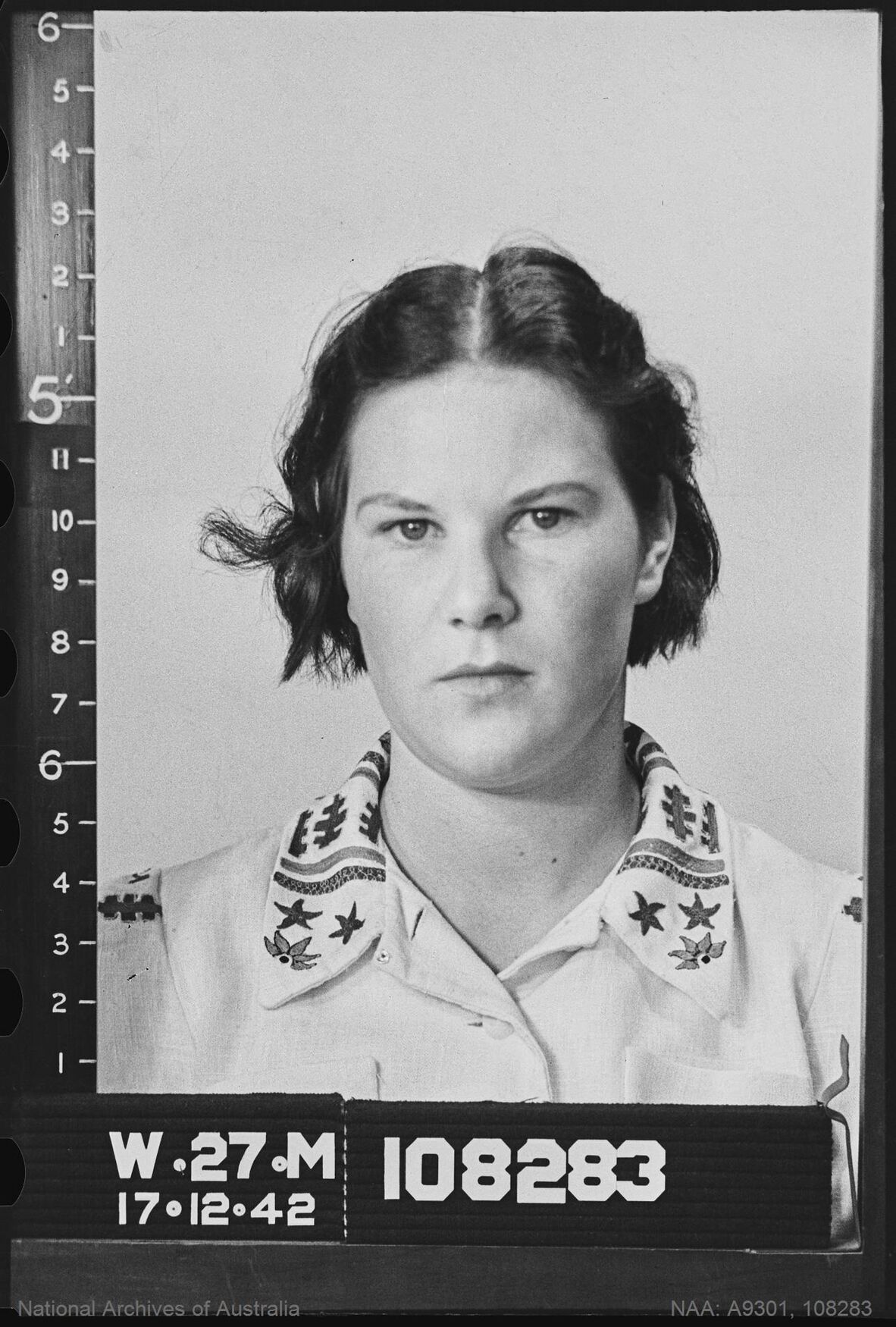

While stationed at Parkes, Charlie met Mildred ‘Millie’ May McGuiness, an 18 year old nursing aide at the local district hospital. A chance meeting led to a quick engagement, with his family later describing the relationship as a ‘hot-house romance’ (Fry 1993: 56). As an attractive young man, Charlie had never lacked for female friends but had always felt financially unable to support a wife. But wartime pressures would change this perspective. With an uncertain future, waiting to marry no longer seemed prudent and reservations were cast aside. The couple seemingly had little in common but took comfort in each other's presence as he finished his training and waited for deployment. Millie promised to write regularly, a comforting thought for Charlie, and was listed in official documents as his fiancée. Sadly, the large age gap and long distance would slowly chip away at this new and fragile relationship, leaving Charlie confused and lonely a world away from home. It was this heartbreak that would later lead Charlie to his second fiancé Bobbie.

Mildred ‘Millie’ May McGuiness, WRAAF enlistment portrait, 1942.

Charlie completed the final aspect of his training at No. 1 Bombing and Gunnery School, Evans Head, New South Wales. Upon his graduation he was commissioned as an officer, with only one in ten wireless operators/air gunners receiving this honour at the completion of their training. After months of training and preparation, he embarked overseas on 16 October 1941 bound for England. This would have felt like the beginning of a great adventure for Charlie, who prior to the war had never travelled beyond Brisbane. The airmen were initially sent to Honolulu, where they were given a warm welcome by the American Red Cross. From here they transited through San Francisco, Vancouver and Nova Scotia before arriving in England on 22 November 1941. It was during this journey that Charlie began to write religiously to his family and Millie, recounting everything from the freezing weather and scenery to his frustration that none of the cooks served baked potatoes for dinner. This was a tradition he would later continue with Bobbie, signing off one of his first letters to her ‘Your loving Aussie, Charlie’ (7 Apr 1943). Due to postage delays Charlie would not receive letters from home until mid-January 1942.

When Charlie arrived in England, he was sent to the Personnel Reception Centre at Bournemouth where he remained for two months stuck in a bottleneck of EATS airmen needing to be assigned to training stations. After several weeks of waiting Charlie was irritated, writing home that he was ‘well and truly fed up with this place’ (8 Jan 1942). These feelings of frustration and inaction were further exacerbated when fighting in the Pacific ignited and threatened the Australian home front. In one letter home in January, he comments the ‘news from Australia is very upsetting’ and that Japanese forces were ‘getting too near’ to the home front for his liking (19 Jan 1942).

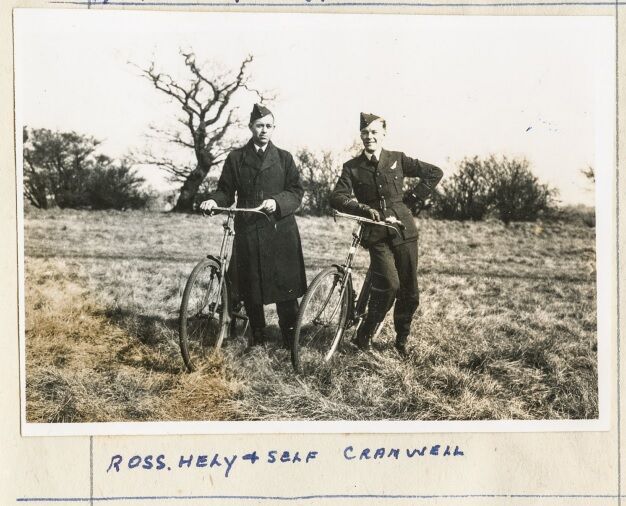

Charles Williams and Ross Hely posing with bicycles while stationed in 1942 at Cranwell, Britian.

In the middle of February 1942, he was finally assigned to No. 1 Signals school at Cranwell, where he excelled at his training as a wireless operator. In April he was moved to 4 Operational Training Unit at Cottesmore, where to his delight they began going up in Hampdens. Although happy to be flying, he noted that the Hampden were ‘good machines but from a wireless operator’s point of view they are the most uncomfortable thing ever made’ (20 Apr 1942). Danger was never far away during training, with all the crewmen learning at the same time. On one occasion Charlie’s crew got lost after all his wireless equipment failed and he had to rig up makeshift bearings to get them home safely. The Hampdens were also notoriously difficult to handle for new pilots, with Charlie describing one incident to his parents:

‘I had quite a bit of excitement on this trip, it was the Pilot’s first solo trip in a Hampden, and he made three attempts at his first landing and nearly landed on top of another plane. I was not scared but was wondering what was going to happen, however we got down without any mishap’.

The Old Hall and Officers Mess at 4 Operational Training Unit Cottesmore, 1942.

Charlie’s first operational mission occurred suddenly when he was pulled from training to fly as a rear gunner in the first Thousand Bomber Raid on 30 May 1942. Codenamed Operation Millennium, the bombing at Cologne had 2 main objectives; to damage German morale while possibly knocking them out of the war due to the scale of the attack, and to be used as propaganda for the Allies. The crew Charlie was placed with were all trainees like him and had never flown together. At this stage Charlie had less than 6 hours of night flying logged and no experience as a gunner in a Hampden. A daunting first operation, especially considering that rear gunners tended to be the target of enemy flack. Despite their lack of experience, Charlie’s crew came through relatively unscathed and he excitedly wrote home:

‘You will have read about the first great raid on Germany on night of May 31st. I took part in this as my first operational trip, and what a raid and what a night. We left about 11 pm and found our target and dropped our bombs without any excitement at all, and the target was just a maze of fires when we left. Shortly after leaving the target we ran into search lights and very heavy flack, but we came through O.K, but had a lively time for a while, about an hour after this we again ran into search lights and flack even worse than the first, but got through although we got a few holes in the plane, we were all damn glad to have it behind us’.

Several of Charlie’s friends and comrades did not return from this raid, a painful reminder of the dangerous nature of operational missions. He was also sent out on the later raids on Essen and Bremen.

Photos of the Hampden Aircrafts used by Charlie's crew for the 1,000 Bomber Raids in 1942.

As Charlie finished his training and waited to be assigned to a squadron, he became increasingly concerned that he had not received any correspondence from Millie. She was never far from his thoughts, and he had written to her regularly, sent numerous cables and even a ‘pretty silk dressing gown’ he had picked up in Vancouver. While he had initially received several letters from her at the beginning of 1942, all correspondence had ceased by March. In May he wrote home that ‘I have not received any mail from Millie for six weeks now, why I do not know’ (5 May 1942). She was also no longer responding to letters that Charlie’s mother was sending to her. By July he feared that ‘something must have happened’ and she no longer cared for him (29 Jul 1942). Despite this lack of correspondence, Charlie’s devotion to Millie was clear when he changed his will in September to leave her ‘a percentage of cash’ to ensure she was cared for if he was killed (13 Sep 1942). His sister Shelia would later claim that ‘I am quite convinced that during the period when Charlie wasn’t hearing from her she was playing around elsewhere- probably with a Yank’ (18 Oct 1943). Millie’s reason for ignoring Charlie remains unknown. Possibly her feelings cooled after the rushed engagement fuelled by wartime pressures.

Join us for part two as we explore Charlie’s time with No. 61 Squadron, his role as a Dambuster and his passionate love affair with Bobbie.

References:

-

An Airman far way: The story of an Australian Dambuster by Eric Fry

Comments

Your email address will not be published.

We welcome relevant, respectful comments.