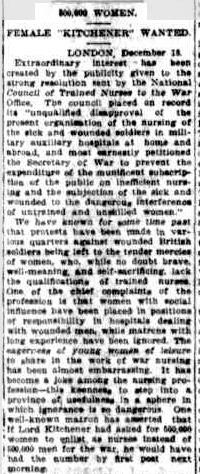

This week in 1915, the Townsville Daily Bulletin published an interesting article outlining the controversy surrounding a strong resolution sent by the National Council of Trained Nurses to the War Office in London. The Council expressed its "unqualified disapproval of the present organisation of the nursing of the sick and wounded soldiers in military auxiliary hospitals at home and abroad, and most earnestly petitioned the Secretary of War to prevent the expenditure of the munificent subscription of the public on inefficient nursing and the subjection of the sick and wounded to the dangerous interference of untrained and unskilled women."

One of the chief complaints of the nursing profession was that well-meaning but untrained women with social influence were being placed in positions of responsibility in hospitals dealing with wounded men, while matrons with long experience were being ignored. While the eagerness of young women of leisure was surely commendable, it was felt by the Council that in the difficult arena of war nursing, ignorance was very dangerous.

According to the article, much of the trouble with 'society' nurses arose from their desire to be photographed for publication in society papers, and that qualified women doing the real work of nursing were too occupied and engrossed in their duties to even think of such a thing. In addition, these society nurses also talked too much about their patients in public.

In conversation with Lord Kitchener, Lord Knutsford, chairman of the London Hospital, disagreed with the resolution of the National Council of Trained Nurses, but admitted that a few untrained nurses may have "got out abroad," and expressed the thought that some, though not the majority, would give less offence if they would be a little more humble and less aggressive, if they would wear their uniforms more modestly, and if they would believe that "the whole universe does not move round them."

Mrs Bedford Fenwick, the president of the National Council of Trained Nurses, stated that the nursing in the stationary hospitals of the War Office and in the hospitals under the Territorial Hospitals Association, was done by thoroughly qualified people, but complaints were abound regarding nursing in the voluntary auxiliary hospitals.

The Red Cross Society asserted that it had not sent out untrained nurses, although Lord Knutsford suggested that the Society was sending out groups of both fully-trained and half-trained nurses.

Mrs Belford Fenwick stated her firm belief that every man who was ready to offer his life for the Empire was entitled to receive efficient and skilled treatment when wounded or sick, and that it was the duty of the War Office to see that he has it. The forthright editress of the Nursing Times suggested that untrained English women were not only working in the British hospitals, but also at hospitals in France and Belgium. She did not believe that the British Red Cross Society and the Order of St. John had sent out any untrained nurses, but expressed concern that the Red Cross Voluntary Aid Departments was not more under the control of the Society. She knew that a significant number of women with first aid certificates had travelled to volunteer at these hospitals abroad, but the hospital authorities did not necessarily understand what trained nursing meant. She emphasised that there was undoubtedly a need for more trained nurses, and there were more than 1000 on the waiting list of the Red Cross Society. It seemed that while trained women were anxious to volunteer, they were being crowded out by amateurs.

Comments

Your email address will not be published.

We welcome relevant, respectful comments.