Under your very nose – the attractions of Longreach

By Guest blogger - Tony Brett Young, writer | 25 February 2019

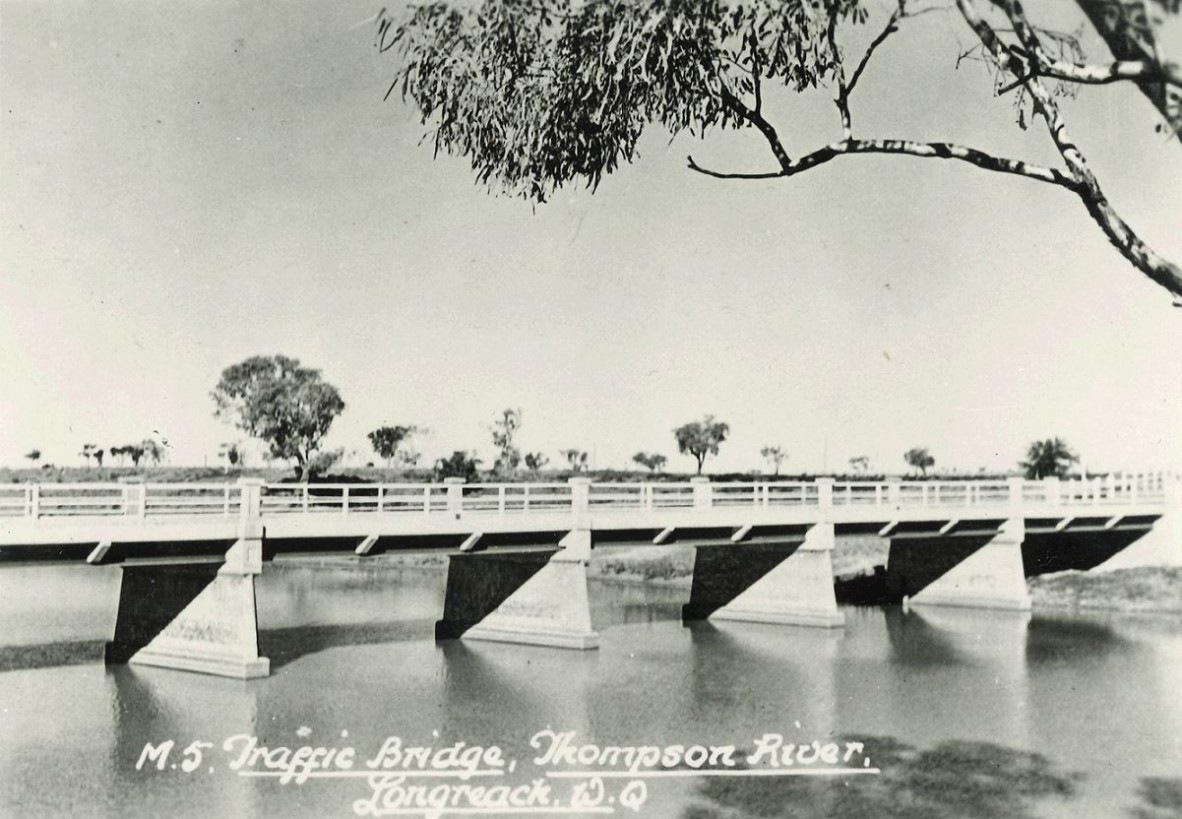

Bridge over the Thomson River, Longreach, ca.1935. John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland. Neg 142950

There’s a saying that if you cross the Thomson River, one day you’ll return to Longreach. I often talk about growing up there - in the outback of Queensland - as a sort of badge of honour. But I haven’t been back since 1975, and that was just for a fleeting day visit. As a family we had first moved to Longreach in the late 1940s having lived for a number of years on the sheep station my father managed outside Quilpie, a couple of hundred kilometres to the south.

View of Longreach, ca.1950. John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland. Neg 157497

As a young man Dad studied medicine at Birmingham University in England. He was from a medical family, but I suspect he discovered belatedly that he was not really suited for that profession. After three years he gave up his studies and in the mid-1920s emigrated to Australia, never to return. He went almost immediately to Longreach to work as a jackaroo, and with his basic medical knowledge became a considerable expert in sheep husbandry – their management and diseases. It was in that capacity that in 1949 he took a job back in Longreach with the then Queensland Department of Agriculture and Stock. He would travel extensively throughout the region advising local graziers how to improve their wool yields, and how to deal with such horrors as fly-strike and barber’s pole worm.

Don (left) and Tony with father Ridley Young at Alaric, near Quiplie. From Bell and Brett Young Family Papers. John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland

My father had managed a number of sheep properties in southwestern Queensland before moving to the Quilpie property which had few comforts. So our move to Longreach, with its population of 3,000, was an exciting prospect for me. We moved into a house on the southern edge of town, in Falcon Street. Like all other streets in Longreach it was named after a bird, so we soon became familiar with street names such as Eagle, Duck, Cassowary and Emu.

Eagle Street, Longreach, ca.1945. John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland. Neg 157454

For all its outback character and rough bush beauty, my memories of Longreach are primarily of its distinctive and lingering smells. More than sixty years after leaving the town I can still recall the varied aromas that were part of life in the outback – the refreshing and welcome perfume of rain on the parched soil and dry gidgee trees; the acrid smell of goat urine in the town’s lanes; the sour smell of the town’s bitumen roads bubbling in century heat; and the sweet smell of oil from ancient lorries leaking onto the dry dust. There were others too such as Californian Poppy, an oily yellow hair oil popular with Longreach teenage boys; and the enticing aroma of pies and sausage rolls carried in the mini-mobile oven mounted on the baker’s delivery bike as he waited to make lunchtime sales outside the school gate.

Even today, as I live in England where a week in the high 20s is a heat wave, I still recall the blistering heat of the Longreach summers – not humid, but still numbing in its intensity. I would sit in my classroom, distracted by the stench of blistering bitumen from the road outside, and which still remains strong in my nostrils. The few sealed streets in the town always seemed to bubble in the summer heat. By contrast, I can recall with joy the excitement of drenching rains after two or three years of below average rainfall. We would stand looking to the heavens, and breathe in the refreshing smells.

View of Longreach, 1954. John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland. Copy print collection

Living on the edge of town as we did, we experienced daily the passing procession of goats as they headed out to graze on the town common. With cow’s milk expensive and in short supply many householders had two or three goats for milking, and at the end of the day as they returned the goats would instinctively know which backyard was theirs. The benefit of this milk came at a price however as the town’s lanes were always foul with the rank and unpleasant smell of goats’ faeces and urine. Children with sensitive nostrils knew to avoid them.

Longreach Shire Hall and Water tower, 1950. John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland. Copy print collection

Then there was the Californian Poppy phenomenon that swept Longreach in the early 1950s. The bright yellow brilliantine came in clear glass bottles, and it was the fashion for many boys at my school to plaster the oil onto their hair to create a ‘cow-lick’ effect. It had a sickly, greasy odour that seemed to revolt our parents but that probably added to its popularity with preadolescent boys. Its application was part of the ritual (along with the wearing of Hawaiian shirts) when preparing for a night at the ‘flicks’ at the Roxy, Longreach’s modest cinema. The Roxy had canvas deckchair-style seats, and Californian Poppy would leave a greasy splodge on the fabric, so wasn’t popular with the management. I felt deprived as my brother and I were not allowed hair oil of any sort.

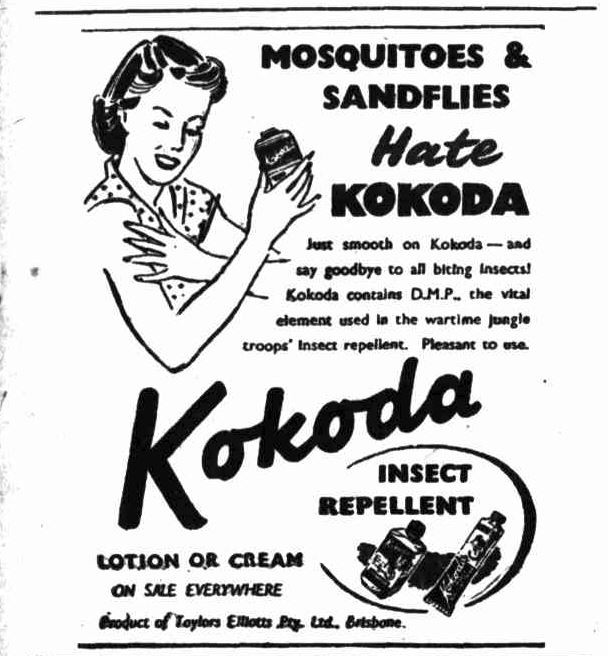

What was mandatory for us, however, was the application of Kokoda insect repellant when the sandflies were at their worst. It had its own very distinctive aroma and was generally quite effective, although there was a story among true bushmen that the smell of dried goat dung, burnt in a billycan, was more effective as a means of keeping insects at bay. But we never left for school without our bottle of Kokoda. On one occasion my mother asked if I had checked that the top was screwed on properly. I assured her it was only to discover later when I came to open my school bag that it had leaked all over my books, but worse still, all over my lunchtime sandwiches too.

Advertisement for Kokoda Insect Repellent from the Longreach Leader, 28 December 1951, p.4 (via Trove newspapers)

The memory of all these smells is still vivid as I write, and I suppose there’s still time for me to return one day to Longreach for a visit, as the old saying suggests I must. And it will be as much to recall the smells of past memories, as it will be to see the sights in the town of my childhood.

Tony Brett Young

Further reading from Tony Brett Young

Comments

Your email address will not be published.

We welcome relevant, respectful comments.