Tin and sandalwood : an early 20th century resources boom in the writings of Ion Idriess and Jack McLaren

By JOL Admin | 16 July 2012

In the first decades of the 20th century, as in the 21st, miners were digging wealth from the ground and Queensland's natural resources were being shipped to China. The miners were digging for tin rather than coal and the Chinese exports were not gas and coal but sandalwood. Two men who spent time in North Queensland in the years before World War One were novelists Ion Idriess and Jack McLaren.

Ion L. Idriess was born in Waverley N.S.W. in 1889. He was educated in several New South Wales towns before attending the Broken Hill School of Mines. At the age of sixteen he began a twenty-five year period of travel around most regions of Australia, working in a variety of jobs, including miner, rabbit-exterminator, boundary-rider, rouseabout, opal miner, crocodile hunter and drover. He served at Gallipoli and in the Sinai and Palestine in World War I. He was badly wounded in 1918. After the war, he continued his nomadic lifestyle, but in 1928 he settled in Sydney to begin a career as a freelance writer.

Jack McLaren was born in Fitzroy, Victoria in 1884, the son of a Presbyterian clergyman. He studied at Scotch College, Melbourne before running away and travelling widely throughout the Pacific. McLaren worked his passage back to Australia around 1901-1902. He spent time in North Queensland as a miner, pearl and beche-der-mer diver. McLaren also worked in Malaya, the Solomon Islands and Fiji. He managed copra plantations and acted as an overseer. McLaren returned again to Australia in 1911 and settled on Cape York until 1919 when he moved to Sydney. In 1924 he married novelist Ada Moore before travelling to London in 1925. McLaren remained largely in the U.K. for nearly thirty years. McLaren published over 30 books and was a frequent contributor to the Bulletin.

Both men wrote autobiographical works and novels based on their experiences in North Queensland in the 1910s. McLaren's 1921 novel The savagery of Margaret Nestor : a tale of Northern Queensland and Idriess' autobiography The tin scratchers, first published in 1959, both deal with the subjects of tin mining and sandalwood cutting on Cape York.

McLaren's novel centres on "Toff" Hammond, a sandalwood-getter, who comes across Tony Nestor, an old tin prospector, in the grip of the D.T.s and chasing imaginary snakes after an ambitious binge at the hotel at Port Landing where he is taking his load of sandalwood to be shipped out. He subdues the old man and carries him on a pack horse back to the Port where the hotel is the only building. As Hammond helps nurse the old miner back from his near fatal binge he learns that the cause of Nestor's drinking spree is the expected arrival of the daughter that he has not seen for 19 years.

Margy Nestor arrives a few days later on the boat from Cooktown and Hammond agrees to accompany the old man and his daughter back to Nestor's tin claim as he has had word of a large patch of sandalwood in the same area. They stop off at Hammond's camp to collect his horses and equipment and also his band of aboriginal workers and they all make the several days journey to Nestor's mine. On the way they run into a stranger who they believe to be notorious claim jumper Henry Martin. They arrive at Nestor's claim where he is keen to explain the workings to his daughter.

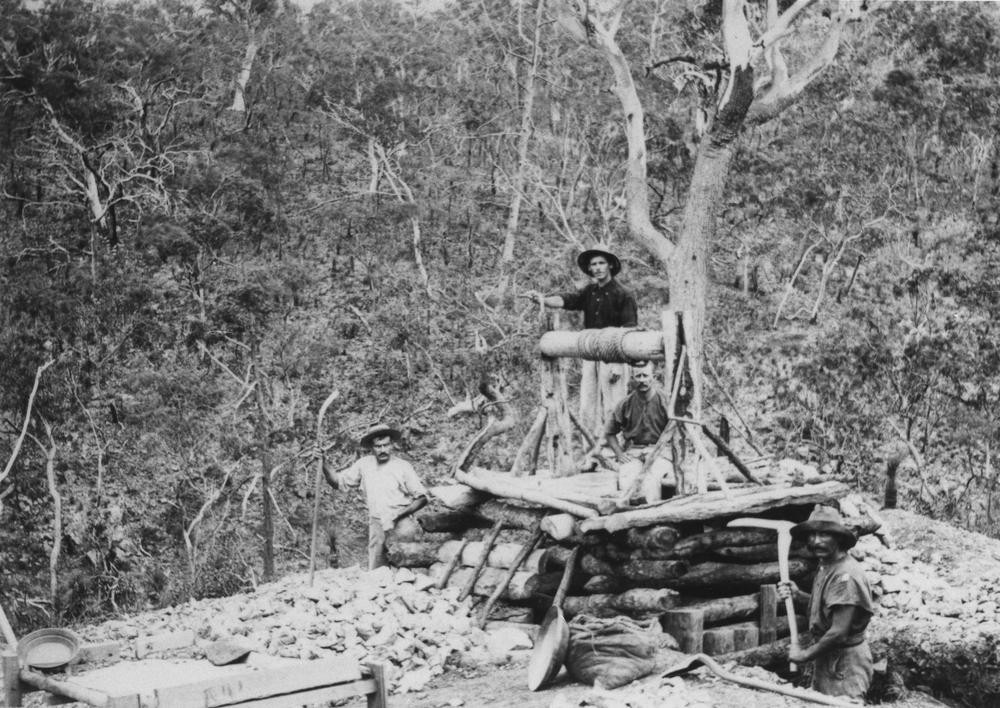

Tin miners at Stannary Hills, 1909

Nestor led the way to the mine. Most of the workings were on the other side of the rise, and in a few minutes Margaret and Hammond were standing with Nestor beside the main shaft. All down the slope and across the hillsides were trenches and shallow holes. Here and there a heap of mullock larger than usual told of deeper shafts.

"I thought I had the pocket in that hole," Nestor said, pointing to one of the heaps. "I put in two months there and got down seventeen feet - and all for nothin'."

"That would almost break most men's hearts," Margaret said.

"It's all in the game," her father said. "You'll find things like that by the dozen on any minin' field. I know plenty of blokes who spent their last bean and nearly busted their hearts with the hard toil of sinkin' through the Lord-knows-how-many feet, chasin' a leader that duffered on 'em. Most of 'em had run into dept, too, and they had to go workin' for wages after to get clear. Prospectin's a great game!"

"It seems to me to call for unlimited perseverance, ability to bear hardship and suffering, indifference to isolation and loneliness, hard work, and a great deal of technical and practical knowledge," Margaret said thoughtfully. "A prospector is a man of parts, indeed."

The main workings consisted of a narrow shaft over the mouth of which was a crude windlass. The windlass was merely a length of tree-trunk about a foot in circumference, with a convenient fork at one end, resting in the crutch of two crossed sticks firmly embedded in the ground at either side of the shaft. Two sticks lashed together to form an "L" and thrust through the fork, formed a handle. Over the windlass was a rough framework, on top of which were some withered branches that cast an indifferent shade. A few yards to the right was a tiny bark shed that served as tool-house and blacksmith-shop. Inside was a forge constructed of ant-bed pounded and mixed with water into a kind of cement. The bellows were made of pieces of packing-cases and untanned wallaby-skin. An oil-drum for holding water for cooling and tempering drills and other tools stood near the forge, and beside it was an anvil that was merely the back of an axe firmly fastened in a stump. A few pieces and strips of hide, a shovel, a single headed pick, a prospecting dish, and a few miscellaneous tools lay scattered about.

After the theft of their horses by the claim jumper Martin, the death of the old man after he tries to throw Martin down a mine shaft, the capture of Martin, Martin's punishment by being made to work cutting sandalwood with the aborigines, Martin is ultimately redeemed as he dies saving Margaret from the flooded creek as the wet season takes over. Hammond wins the heart of the strong-willed Margaret and a fortune in tin and sandalwood is theirs for the taking.

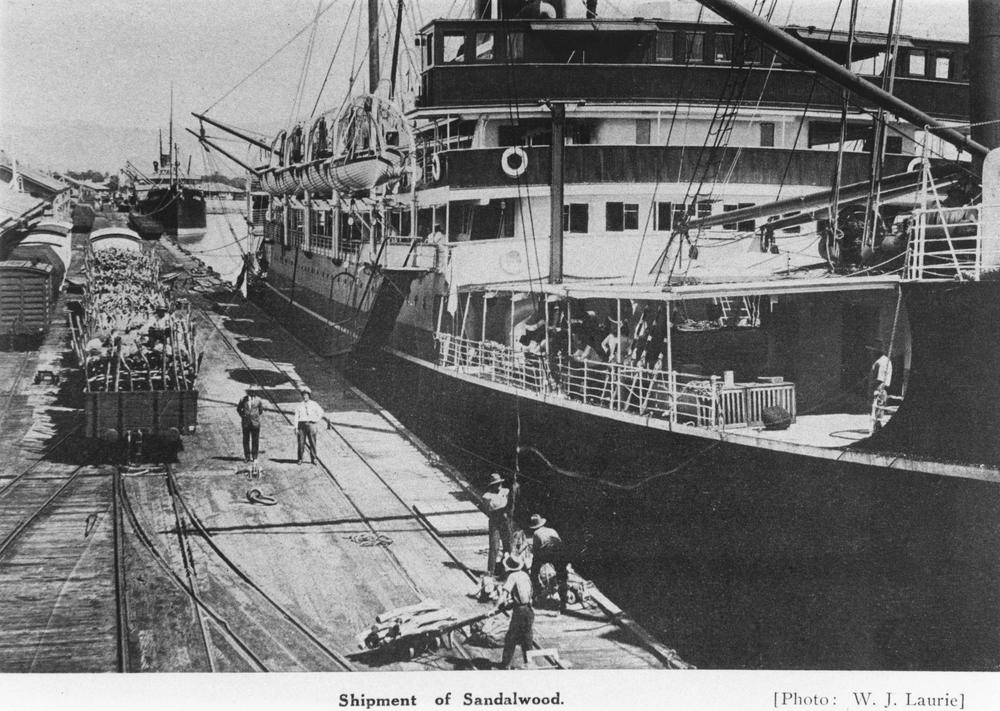

Shipment of sandalwood at a wharf in Townsville, 1929

Ion Idriess' book deals with many of the same themes as McLaren's novel although without the obvious romantic elements. It contains a wealth of descriptions of tin mining operations of many types and the many colourful characters involved. Here a group of men compare the hardships and benefits of tin mining and sandalwood cutting.

"There's 400 tons of sandalwood stacked on the wharf awaiting a China-bound boat," remarked Harry Ashford the tentmaker. They're expecting the Empress of China."

"A patch of sandalwood is as good as a patch of tin these days," said a tin scratcher from Mt Poverty longingly, "even better, if you've got a good plant."

"A hundred horses and their packs take some getting together," Shipton from Shipton's Flat said good naturedly. "After all, all we want is water and our few tools and a hut, and to be in good with the storekeeper."

"All the same, I'd like to have the value in tin that came in on that eighty-horse team from the west coast this morning," drawled Ted Parsons

...

A wiry looking chap from the Mitchell, hunched up on the form, shifted a short clay pipe from one corner of his bearded mouth to the other.

"I've ridden past many a patch of sandalwood,", he muttered, "... Never gave a thought that I was riding past yellow gold. One thousand, one hundred and twenty golden sovereigns growing up out of the ground in grubby-looking little trees right under me very eyes. Many a time - phew!"

"You're not the only one," Shipton said. "I'll admit I'd like to find a patch of the yellow wood, but I'd rather find a patch of eight tons of tin. The sandalwood-getters come up against plenty of knock-backs, same as we do - more so! First, those two boys who came in this morning had to risk their entire capital, plant and tucker bill; then they had to scout over a lot of hard country, risky in parts too, on the chance of finding a good patch. They found it. Admittedly to cut the wood it cost them only three months' labour, and the cost of the tucker and presents for the natives. Then they packed the wood into port - say six months from go to whoa. They lost one of their blackboys, and a good horse boy he was too, speared on the Kendall. Lost five horses: three were speared, two rolled down a gully and broke their necks. Jim's mate near perished of maleria; a blackboy had to ride beside him and hold him in the saddle for the last hundred miles. Still, it was worth it!"

Biographical information on Ion Idriess and Jack McLaren is from AustLit, one of the databases available throughout Queensland through the State Library.

Comments

Your email address will not be published.

We welcome relevant, respectful comments.