Guest blogger: Mark Clayton.

Notions of personal responsibility and safety mustn’t have counted for much when I was nineteen, else I mightn’t have risen early one winter’s morning in 1978 thinking – or not thinking, more probably - then I could make it back in time for dinner that same evening and still have time enough for a five-hour motorbike ride (through the dark); for crossing a notorious ocean channel in an open dinghy (having never used one before); for navigating my way through labyrinthine mangroves armed with nothing more than a mud map; and then boulder-hopping my way for another four hours up a precipitous 922 metre high mountain.

The carrot on this occasion was the wreckage of the Texas Terror, an American B-24 Liberator bomber that had crashed into the summit of Hinchinbrook Island's Mount Straloch in mid-December 1942 killing all twelve on board.

It was still dark and chilly at 4 am on Saturday 29 July 1978 when we headed off from Townsville's James Cook University, bound for the tiny coastal community of Lucinda some 2½ hours ride away. It was an uncomfortable bone-jarring journey along the pot-holed Bruce Highway for myself, and my six-foot pillion passenger (who had never been on a bike before). My noisy Yamaha DT250C motorbike held just enough fuel for the one-way trip (there being no intermediate service stations open back then).

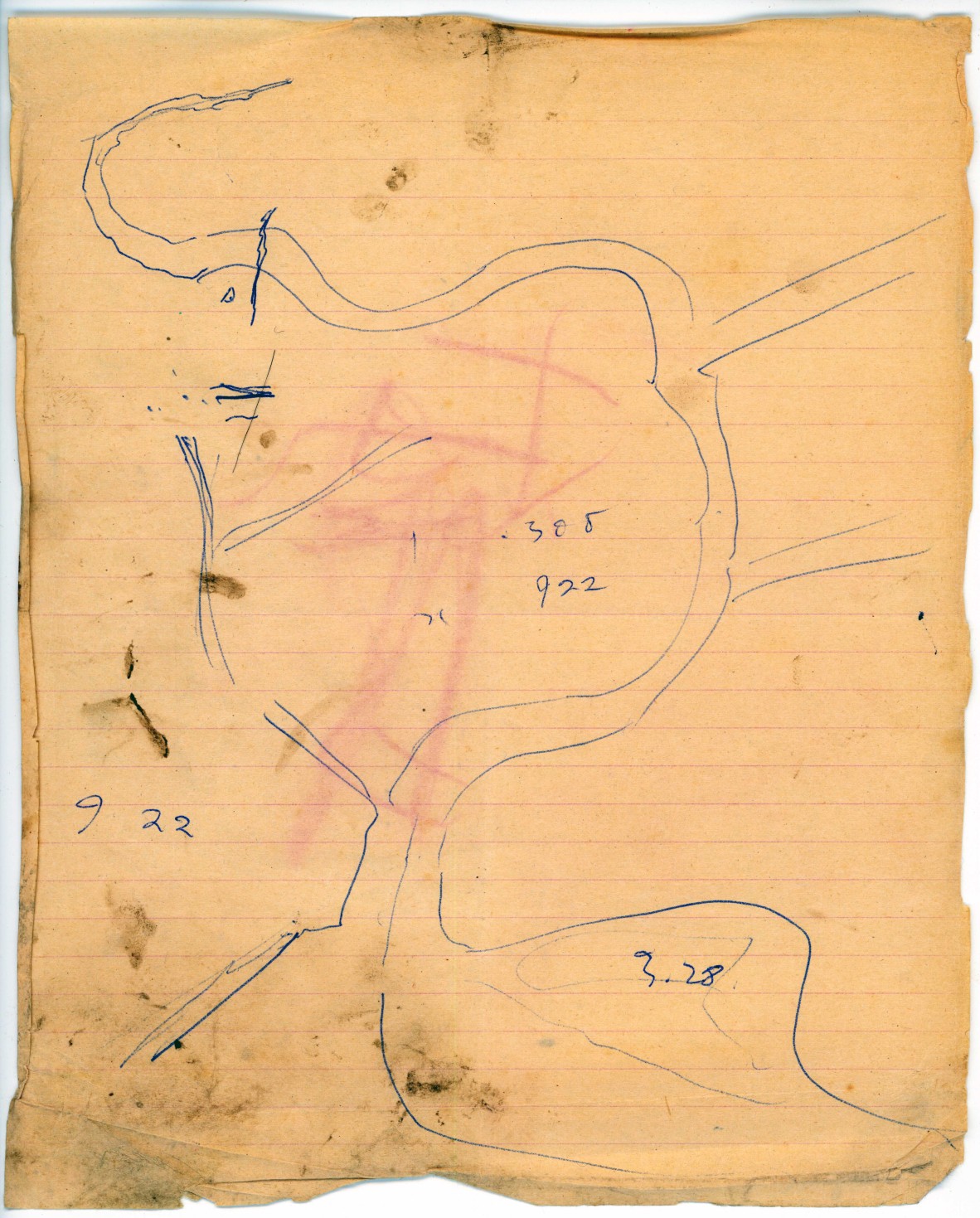

Numbed by the cold and vibration we eventually arrived at Lucinda only to find the Mount Straloch summit, eight kilometres to the north, engulfed in heavy cloud. Thinking we'd already suffered too much to turn back we exchanged $15 for a tiny aluminium dinghy; a 4 h.p. Chrysler outboard; a one-minute explanation on how to operate both and, most importantly; a hand-drawn mud map showing the best route through the dense mangroves that fringe the Island's south-western shores.

There followed another agonizingly slow journey - this time across the channel - before we set out on foot, hoping all the while that we'd navigated up the correct creek branch and ravine. For the next four hours we continued ascending, captivated by the stunning rainforest and encouraged by occasional discoveries, the first being an engine exhaust shroud with the part number ‘32P10047’ still clearly legible. This provided the first clue that we were on the right track because, despite having performed poorly as an undergraduate history student, I had nonetheless somehow acquired a deep understanding of the part-numbering systems being used mid-century by U.S. aircraft manufacturers (yes, I was still single). The '32' prefix was used exclusively to distinguish B-24 components (the latter being known otherwise as the Consolidated Model 32), while the 'P' simply indicated that this belonged to the powerplant (i.e. engine) sub-assembly. Hours later we come across the mangled form of a radial aircraft engine, and mistakenly began thinking we were almost there.

A forty-one year old diary entry records those feelings of anguish and growing fatigue…

'If I had to explain it all to someone else I would say 'climb beyond that point where you've lost all hope where, even a fool would give up. Go on until you can touch the cliff face and see beyond to Palm Island.'

Even when eventually we reached the main impact site we looked up to see a memorial cross and another massive piece of wreckage hanging precariously further up the mountain. We might have gotten there if we had continued climbing for another half hour, the prospect of a night-time descent and channel crossing however being enough to banish all thoughts of pressing on.

With the cloud base having lifted hours earlier, we paused just long enough to take in the magnificent views of Halifax and Lucinda, ringed by patchwork cane fields.

Perhaps because the site was difficult to access (and because the B-24 was the largest aircraft used during the war in the South West Pacific) there was lots of wreckage still in situ, including seven Browning machine guns and a Thompson sub-machine gun. The litter also included Australian .303 inch ammunition which is somewhat odd, given that those on board were all Americans. And everywhere so it seemed there were red (tracer) and green (incendiary) tipped .50 calibre machine gun rounds. Amongst the charred and shattered wreckage I even found a toothbrush ('Made U.S.A.'), a poignant reminder that a dozen others - not much older than ourselves - had perished here. Elsewhere we found bomb racks, fuel tanks, engines, wheels, radios and lengths of twisted wing and airframe, the American Air Force star insignia still evident on one piece. The shattered rubble testifies to the violence of the impact.

One hundred metres below the main crash site at around 460 metres was the most substantial and recognizable piece of airframe, the massive starboard tail fin with the plane's yellow serial number (123825) clearly visible against the camouflage-green background.

The factory-new Texas Terror was being delivered to the American 90th Bomb Group's base at Iron Range in North Queensland when it crashed during a violent storm. It had cost the American taxpayer $289,276 having departed Hawaii for Australia on 3 November 1942. A search at the time failed to find the missing aircraft until, almost a year later, two Aborigines searching gullies on Hinchinbrook Island for alluvial tin reported finding some burned U.S. currency in the creeks at the southern base of Mount Straloch (it is alleged since to have been carrying a payroll for U.S. servicemen in New Guinea). This was the fourth B-24 (and crew) that the 90th Bomb Group had lost in almost as many days.

Amazingly someone had recently sawn off one of the bomber's twisted propellers leaving a trail of scratched rocks which we only noticed during our descent. A pair of these blades - we later learned - had been retrieved two years earlier at the behest of a local Franciscan priest, Father Publius Cassar, who then had them erected as memorials in the Lucinda Catholic Church (one having since been relocated to the Lucinda foreshore).

As a teenage landlubber I hadn’t given any consideration to tidal movements which, by good fortune, was to favour both our outbound and return crossings.

We arrived back in Townsville at 7.30 pm having consumed nothing all day other than a cup of cocoa and some raspberry yoghurt. The day’s diary ends on a more sobering note…'never have I been so cold and foolish'.

Mark Clayton

Comments

Your email address will not be published.

We welcome relevant, respectful comments.