Sound as historical material: developing a new way of cataloguing, describing and accessing sound in the archive - Part 1

By Perrin Ellis, 2019 Mittelheuser scholarship-in-residence | 24 October 2019

Guest blogger: Perrin Ellis - 2019 Mittelheuser Scholar-in-Residence.

I’m the Mittelheuser scholar in residence, which means my job is to “develop new ideas, tools, strategies and services” for the State Library and other Queensland cultural institutions. In my case, I’m working on the idea of sound as historical material—uncovering the sounds of the past as a way of knowing about the past. This comes out of my background as an artist and designer making multimedia installations that deal with local history; in fact I was part of the Home exhibition at the State Library earlier this year.

If we can think of sound as something to archive and display, like the objects and documents in the library’s collections, what does that mean for how we catalogue them, curate them, and make them available to the public? A lot of archival material in the Library’s collection that might have sound components aren’t immediately obvious in the way they’re described in the catalogue; they’re hidden behind simple titles like “film” or “newsreel.” For that matter, if we do know a particular archived film has sound, how do we know what sound, or where it is in what may be a very long file?

For this project I’m concentrating not on spoken word, but on other, environmental sounds; what the past sounded like. These sounds — trafficless vistas, the sound of mangles in suburban backyards — can be a very evocative way of bringing a sense of the past into the present. Those affective moments then form the nexus of a way for us to find about the past, the concrete details that make the past real and inspire us to learn more.

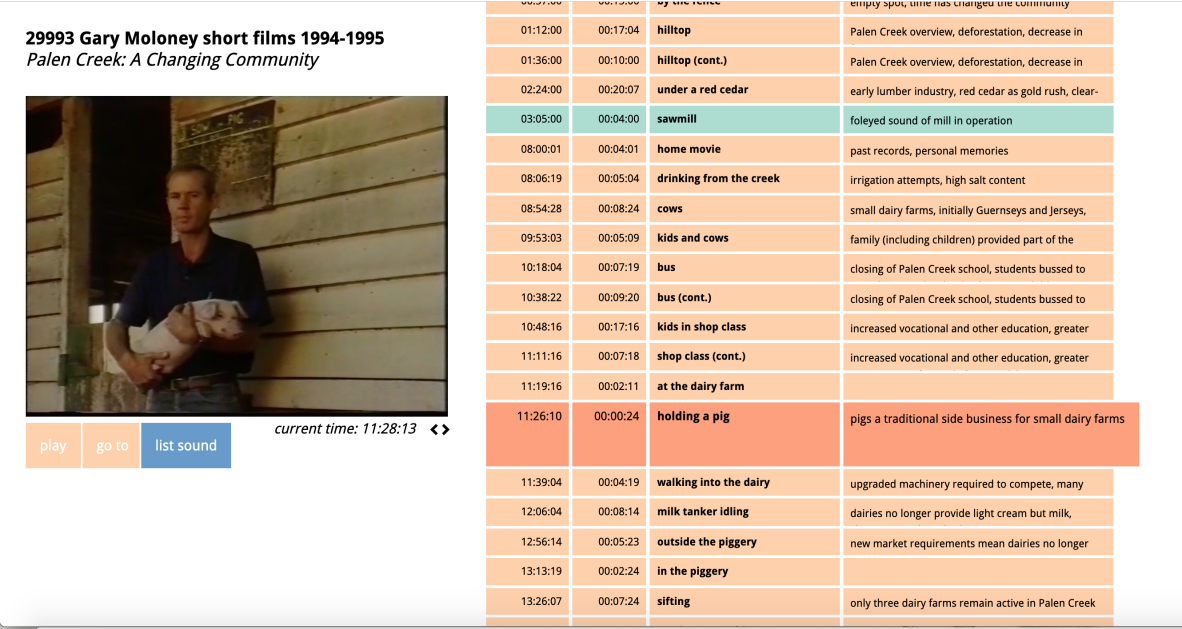

When I began this project I thought my first move would be to do an audit of the Library’s materials that do, or might, have sound aspects. But first I had to figure out how to record sounds once I’d found them. So far I’ve spent a lot of my time building software tools that allow me to create and add to a catalogue of sounds in the various media sources I’m looking at — mostly videos and audio that have already been digitised and are available online. I’m creating summaries or “transcriptions” of original sounds in these media sources. My first test subject was the documentary Palen Creek: A Changing Community, made by Gary Moloney in 1994. Starting there, I’ve begun to create a catalogue of dozens of sounds so far across multiple video and audio files.

A sample of original sounds on the documentary, Plan Creek: A Changing Community. Image courtesy of Perrin Ellis.

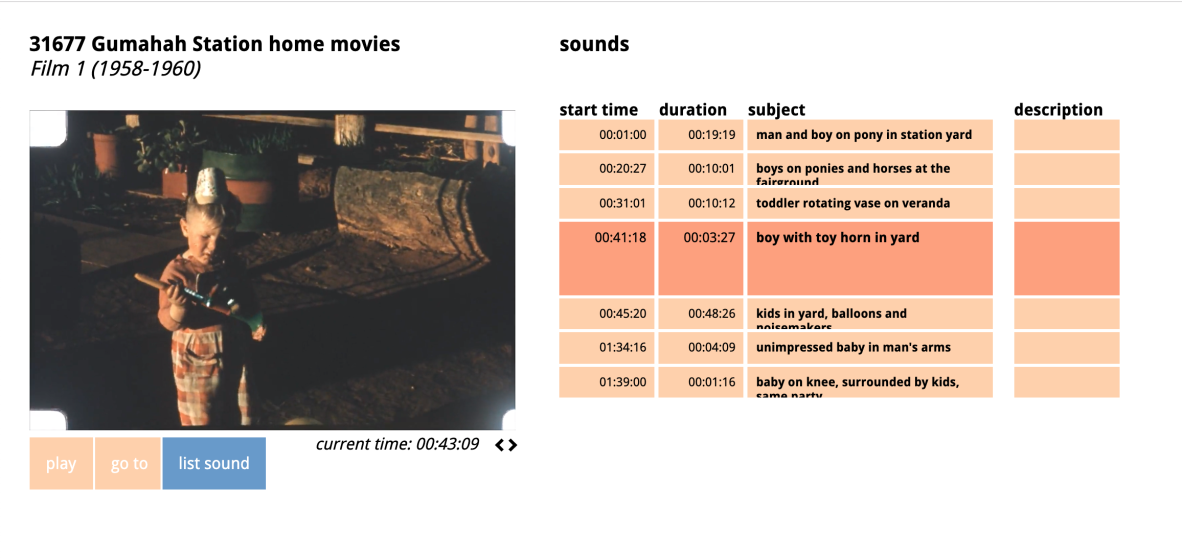

One interesting thing that’s come up for me is how to deal with silent media, like home movies. Should I just label them “soundless” and move on? There’s something interesting, at least for me as a researcher, in identifying the sounds that aren’t there. Part of why I’m attracted to sound as a subject for historical research is that in the real, physical world, sounds come and go so quickly; silent films remind me of all the sounds we can’t access any more. Perhaps it could become an interesting source of historical research, asking people who were there to fill in with their sonic memories of that time and place. Already I’ve found that not only the sounds themselves, but the way people remember and describe sound, is a powerful way of calling up the past.

Summarising "missing sounds" on the silent Gumahah Station home movies. Image courtesy of Perrin Ellis

In the end, I’m using this project to create structures and strategies that will help not just me, but other people find and tell stories more easily in the future.

Perrin Ellis

Also see Perrin's second blog - Sound as historical material: developing a new way of cataloguing, describing and accessing sound in the archive - Part 2

Research Reveals: sound as historical material. Presentation by Perrin Ellis, 2019 Mittelheuser Scholar-in-Residence about his project and time as Queensland Memory Fellow.

Comments

Your email address will not be published.

We welcome relevant, respectful comments.