Rare photos from the 1919 Influenza epidemic in Queensland

By JOL Admin | 9 April 2020

Guest Blogger 2019 John Oxley Library Fellow, Matthew Wengert. The Covid-19 pandemic is occurring in an era of hyper-abundant photographic images. It might surprise some people how few images there are from the 1919 Pneumonic Influenza (‘Spanish Flu’) epidemic in Queensland. State Library has the largest available collection of rare photos from that major moment in the State’s history (Queensland’s deadliest disaster by far). But there are only a couple of dozen images, from only a few places.

Portable photography was just beginning to become affordable and available to affluent people in the 1910s (decades later it would be accessible to most people). Kodak was in the early phase of revolutionising photography through advertising cameras and film to enthusiasts. Previous to this photography was the domain of professional studios. A little over a century later and we now carry cameras almost everywhere we go. When I researched the 1919 Flu epidemic I was quite shocked by the scarcity of photographic documents. [My research was funded by Brisbane City Council’s Helen Taylor award for local history, resulting in a book titled City in Masks: How Brisbane Fought the Spanish Flu (AndAlso Books, 2019). This is a link to the catalogue record in the John Oxley Library

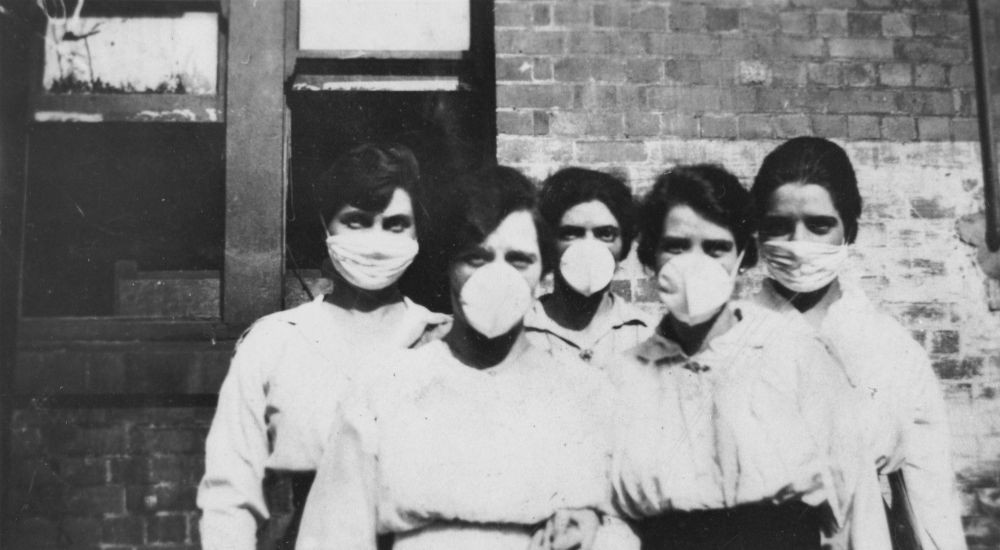

With so few images, all of them are historically valuable––but two photos in particular seemed very special to me, and adorn the covers of my book. One of them is very enigmatic and symbolic. We don’t know who took the photo, or who the women in it are. The other is an excellent visual document of the fight against the Flu in one part of Brisbane.

It is May or June, 1919. Five women stand together, facing the camera with a direct gaze––looking at us from a century ago. There’s a simplicity, a plainness to the group––dressed similarly in white blouses with collars and long sleeves, their hair pinned back––standing in front of a nondescript brick wall. They may be friends or neighbours, possibly sisters or cousins––but what has brought them together this day is silently and starkly announced by the singular feature of the image: their face masks. The masks identify their common cause, their belonging, their vital work as emergency volunteers.

They are front line combatants, whose protective armour is a flimsy fabric cover designed to keep virus-laden airborne droplets from entering their lungs through the mouth or nose. Equipped with these masks, which hid much of their face while signifying the collective importance of their group, the women could confront the deadliest event in the city’s history and perform their vital work with some necessary measure of confidence and courage.

These women––five among more than a thousand equally impressive women volunteers in all parts of the young city––proved their bravery and strength by turning up, despite the exhausting work and worries that left heavy bags under their eyes, to do what had to be done. Tying these small masks over their face, they stepped forward to meet certain and imminent dangers literally face-on. They risked their lives day after day, by doing profoundly basic humane work––cooking and feeding people, cleaning them, comforting them with words of reassurance, sitting with them and holding their hands or mopping their brows so that the stricken people knew they were not alone as they personally struggled with the most intense and widespread pandemic in human history.

It is one of the most iconic images of Australia’s worst natural disaster. This photo from the John Oxley Library collection has been used to illustrate articles and stories from many national and state media outlets (eg. ABC website, Brisbane Times, Sydney Morning Herald). It is easy to see why. The masks give this image its power. They symbolise the danger of this very deadly event, and the bravery of the women who fought the disease––whether they were nurses, working long shifts in hospital wards packed with gravely ill and highly infectious patients, or if they were the volunteers who worked tirelessly to keep people alive in homes throughout the city. Many courageous men also fought the Flu, in different ways, but it was mostly women who came to grips with it in the epidemic front lines. Their experience of the disease was more intimate, more physical, and often more prolonged. Brisbane was lucky to have such strong Flu-fighters.

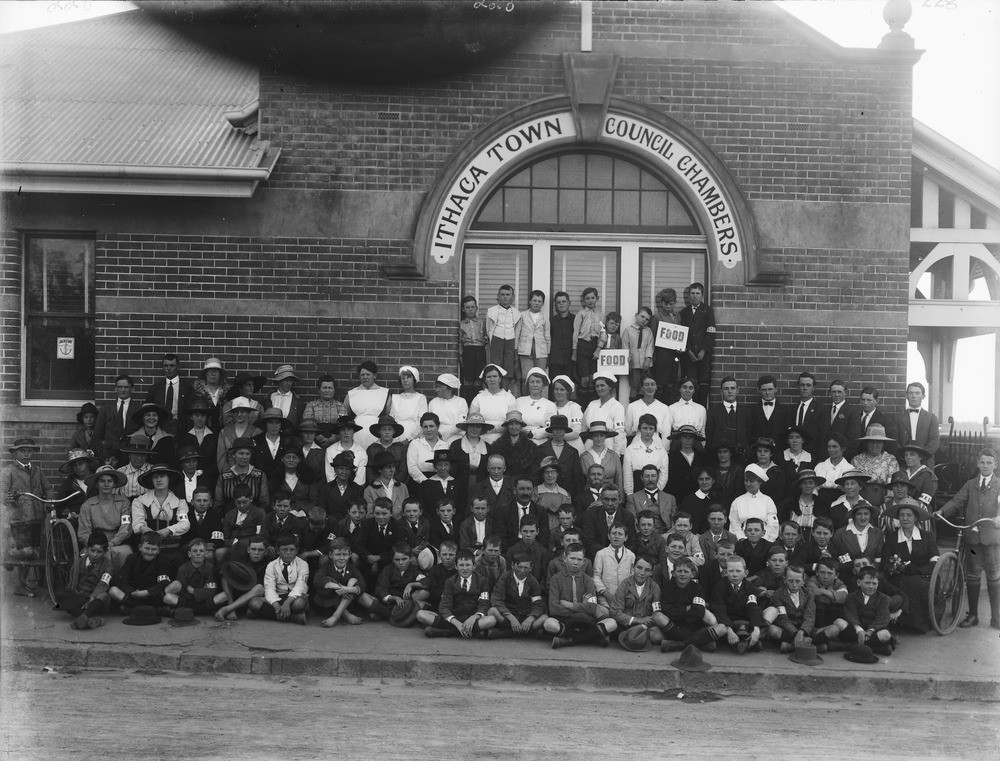

This photo is part of State Library's collection of the Barnard, Lawrence and Loane Family glass slides. The very high visual quality of this image allows the numerous individuals in the group portrait to be seen in great detail. The various people in the group were participants in the volunteer response to the Flu epidemic. Some of the women are wearing ‘W.E.C.’ armbands, identifying them as Women’s Emergency Corps volunteers. A couple of the boys standing on the window ledge at the back of the group are holding ‘FOOD’ placards, which had ‘S.O.S.’ printed on the other side, and which were printed by the Queensland Government Printing Office and distributed by local authority’s to every household in Brisbane (and other cities across Queensland). The many boys in the group, including the two holding their bicycles, were part of the Ithaca Boys Bicycle Brigade, which was formed to patrol the streets each day during the epidemic, reporting back to the WEC women which houses had their ‘S.O.S.’ or ‘FOOD’ placards in their windows, signalling that the occupants needed assistance.

This is a celebratory commemorative photograph, taken after the people captured in it had fought the 1919 Flu epidemic in the densely populated suburbs of Paddington and Red Hill. These volunteers recognised that their efforts were historic: they had certainly prevented many deaths, and alleviated much suffering in hundreds of homes during the months of May to July. The work they did was humble, but it was also heroic. They faced the deadliest disease in human history, armed with food and fortitude. The organisational impetus behind this life-saving work is shown in the painted sign above the epidemic kitchen––so many women, working long hours, day after day, cooking and distributing thousands of meals to families too sick to take care of themselves, and for nothing more than the satisfaction of doing what they could for their community. The bunting of Allied flags reminds us that the war had ended not long before the Flu arrived, and now that the epidemic was waning in July, it coincided with the city-wide celebrations of the Treaty of Versailles (signed at the end of June, 1919). It was the women who rolled up their sleeves, and tied on aprons and face-masks, to keep their stricken neighbours alive with food and comfort––but the boys and some men helped too, with patrols on bicycles and in a few cars (when Brisbane had few cars).

It is unfortunate that most other parts of Brisbane do not appear to have similar photos of the Flu-fighting teams. The South Brisbane Vigilance Committee was captured in a group portrait, which was published in a newspaper, but my research for City in Masks could not discover other similar visual documents of the groups from any of Brisbane’s other local areas.

Most of the John Oxley Library’s collection of photos relating to the 1919 Flu epidemic are images of the Wallangarra quarantine camp, at which hundreds of Queenslanders––who’d been inter-state when the border was closed at the end of January––had to stay for up to 10 days each before they could return home.

There are 18 photo postcards of the Wallangarra camp, two of which are online. These two are similar versions of the same group of people at the same location, taken a few minutes apart. The same caption inscribed on both of the images says ‘Arrival at Quarantine Camp. Wallangarra. 7th May 1919’. The photos show several dozen people, including children, with luggage––having presumably arrived by train––gathered in front of some tents. Some men are in military uniform. At least a couple of uniformed police are in attendance. The portion of the camp within view includes almost thirty fairly large tents in four rows, as well as a corrugated iron amenities block. A few people are wearing masks, but most are not. A single-strand wire boundary is discernible in the photos, running across the area in view (some of the people are behind it, some are beyond it), about a metre above the ground––this was the actual fence that demarcated the quarantine ground.

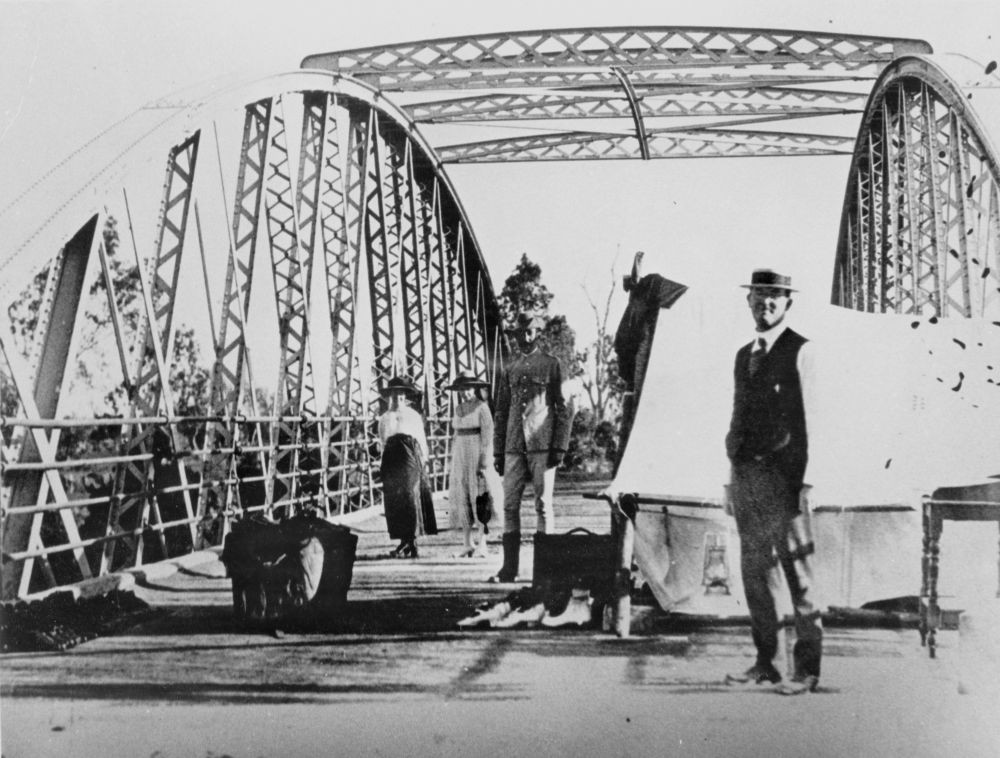

There is a group of three photos that depict the closure of Queensland’s border with NSW. This photo’s caption says, ‘Border Restrictions. The Bridge. Goondiwindi.’ The image shows two uniformed police officers standing next to canvas tent, erected in the middle of the bridge (a temporary police station in the middle of a bridge across the border is about as good a way to enforce travel restrictions as I can think of). A heavily loaded dray is moving away from the camera, and several people stand near the metalwork structure along the side of the bridge.

The photographer (H. Rickard) has captured a police officer in a slouch hat and calf-length boots, standing next to a man wearing a straw boater, and holding a pipe, next to an arrangement of dozens of pairs of shoes laid out on a couple of boxes and the road surface of the bridge. We can surmise the man is a travelling shoe salesman, but the reason his wares is not so easily guessed at.

The same police officer and gentleman as in other photo (Neg. 194295), and two ladies wearing straw hats are standing in the near background. It appears to be late afternoon, because the long shadows cast by the figures and the police tent would suggest the sun is low––and the man in the boater hat is not wearing a coat, so it’s probably not an early mid-winter morning in Goondiwindi.

Newspapers, such as The Daily Mail and The Queenslander, published several photos of people and places relating to the Flu epidemic––including notable images of the Coolangatta quarantine camp, and the Isolation Hospital buildings at the RNA Exhibition Ground, as well as a group portrait of the South Brisbane Vigilance Committee––but the visual quality is comparatively poor. These are discoverable by searching State Library of Queensland's catalogue, or via Trove.

Matthew Wengert April 2020.

Comments

Your email address will not be published.

We welcome relevant, respectful comments.