Queensport Aquarium: Queensland’s first amusement park

By Chris Currie | 22 August 2025

Queensport Aquarium Estate, Hemmant, 1889.

Among State Library of Queensland’s impressive collection of vintage real estate maps is a striking design for Queensport Aquarium Estate in Hemmant, complete with a mermaid and sea creatures. Why does it have this name? The answer uncovers the fascinating story of what is considered to be Brisbane’s first amusement park.

Planning Queensland's first amusement park

In June 1889, the newly formed Queensport Aquarium Company (headed up by the director of Sydney’s Bondi Aquarium, Charles Anderson) announced the purchase of about 600 acres of ground to establish a township at Queensport, on the lower reaches of the Brisbane River – already home to a school, residences and meatworks.

Eleven acres were also put aside opposite Gibson Island, ‘for the purpose of establishing an aquarium, gardens and a number of amusements’. Adjoining the aquarium grounds were the ‘684 magnificent allotments’ of Queensland Aquarium Estate, ‘bound to become the seat of a large suburban population’.

Despite its distance from the centre of Brisbane, the aquarium – it was reported, would soon be serviced by the soon-to-be-open Cleveland railway station and ‘a line of steamers’ proposed to run at short intervals throughout the day.

Hand-drawn map showing Queensport Aquarium Estate, taken from Hemmant State School 1864-1989 : a history of the school and its community.

The grand opening

On 7 August 1889, only a few months after construction began, over 130 gentlemen ‘and a few ladies’ boarded the company’s newly acquired steamship, the Woolwich, at Campbell’s Wharf on Creek Street to take the 45-minute journey to Queensport Aquarium.

The visitors were greeted by ‘a two-story [sic] structure of wood and iron’, six huge fish tanks, a three-tiered fountain and a large fernery. Upstairs was a 1,400 seat concert hall, complete with two dressing rooms, plush drop curtains, an electric self-playing pipe organ and dining room.

One of the few images referencing Queensport Aquarium in State Library collections. An advertising sign can be seen in the background of a photograph showing the intersection of Elizabeth and Creek Streets following the 1890 floods in Brisbane.

Soon the Aquarium was open to all and proved an enormous hit with the public. A ‘bewildering number of amusements’ at the site included a switchback railway (an early form of rollercoaster), flying machine, camera obscura, swings and merry-go-rounds. A first-class cricket ground was also built on the site, and by November it was hosting matches in the local Brisbane competition (with players taken to and from the match on steamers). Open spaces were also used for lacrosse, athletics, bike racing, tennis and lawn bowls. Sculling and yachting took place in the river nearby.

On 10 September 1889, electric lighting was installed, which allowed the Aquarium to stay open three nights a week. Beyond the existing day trips, visitors were now able to take twilight cruises to evening dances and concerts.

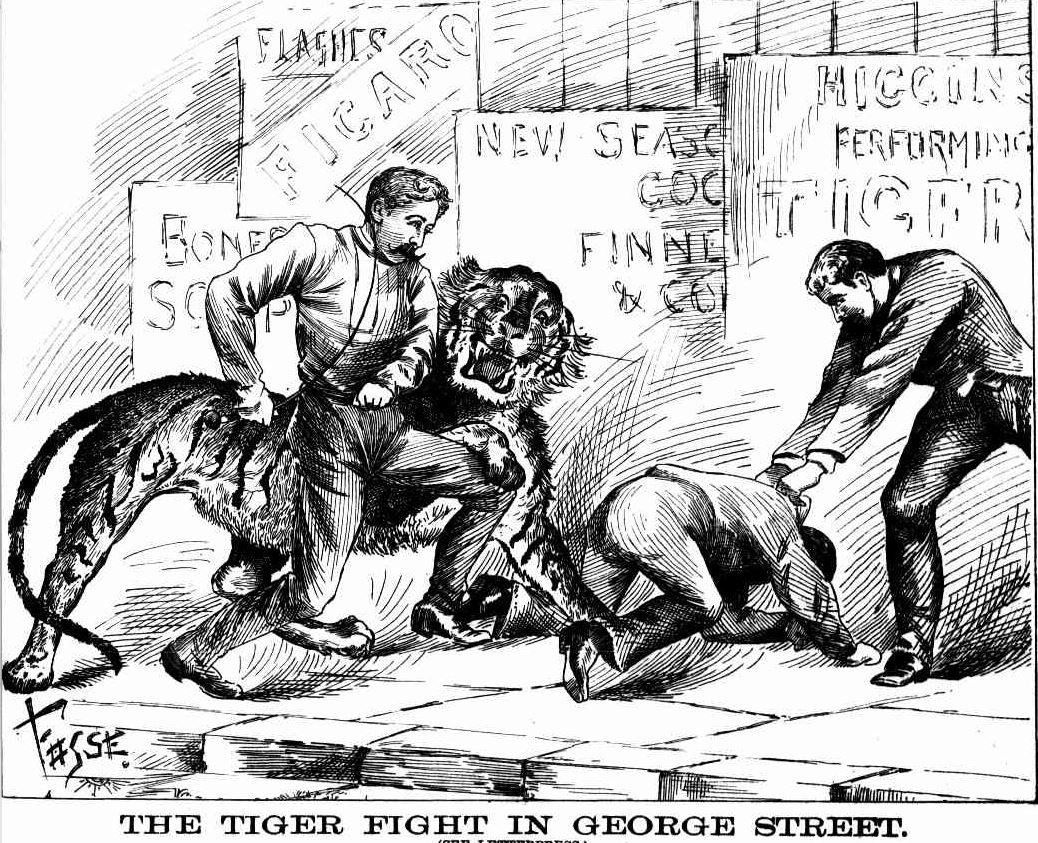

Illustration published in the Queensland Figaro and Punch, December 1, 1888.

The other main attraction was a collection of animals including lions, tigers, bears, cheetahs, monkeys, birds and snakes. The collection of animals had been bought from Charles Higgins, former operator of a ‘Great Menagerie’ in the centre of Brisbane who was forced to give up his lease after one of his tigers escaped its cage and mauled an attendant on George Street.

‘In the grounds the great attraction now is the seal tank, where four of these slimy, footless creatures apparently delight to show visitors how to dive and swim’ (Image P53985, Royal Historical Society of Queensland).

New Heights: Aquarium the place to be

By the end of 1889, the Aquarium was an immense hit with the Brisbane public, and the company employed three steamers – The Alice, Woolwich and Natone to ferry the tens of thousands of visitors to the site. A huge celebration was held on Separation Day (including ‘the well-known “pigs in a clover” puzzle ... played with live pigs [and] climbing the greasy pole’). On Thursday 16 December alone, it was reported 10,000 people visited. Reports on 27 December were of crowds waiting for too long in the boiling sun, and even becoming violent in efforts to board one of the overcrowded steamers.

By 1890, you could buy season tickets, and it was abundantly clear that ‘the Queensport Aquarium ... was now recognised as the most popular resort in and around Brisbane.’ Already the company was making plans to add new stops to its steamers to meet demand, and by 1891, the Woolwich was taking 12 trips a day.

A Queensport Aquarium enclosure with a black swan and pelican. In the background is a camera obscura (Image P53984, Royal Historical Society of Queensland).

Balloons, bullets and a machine that cried ‘mamma’

The aquarium manager Charles Anderson was always on the lookout for unusual entertainment. One of the most unusual was Herr Renier’s Electric Orchestra Militaire, a ‘curious mechanical contrivance’ made up of 37 miles of electrical wire powering ‘beside the grand organ, bugles, side drums, chimes, tambourines, triangles, castanets, zither, gongs, cymbals, lightning boxes, mounted guns, rain and hail machine, the cuckoo and the mocking bird, a crying child, and a machine which cried out “mamma”’. The full description of the show describes a replica of the battle of Trafalgar, a model train and large self-striking anvil.

If this wasn’t entertainment enough, a 9 year-old girl purported to be Renier’s daughter also performed as Lillian the ‘champion child shot’. Lillian wowed the audiences with her artillery prowess, including ‘shooting corks from off an intelligent terrier’s head’.

A similar aerial performance from Spanish aeronaut Christopher Sebphe at Toowoomba showgrounds in 1908.

Topping perhaps even this was a performance from aeronaut Professor Fernandez, who announced in May 1891 that he would perform a ‘balloon ascent and parachute leap’ above the Aquarium. Fresh from a ‘very successful’ residency at Bondi Aquarium, his plan was to inflate and float up a hot air balloon, from which he would hang from a trapeze, before letting go, inflating his parachute and floating safely to the ground.

Wearing ‘scarlet tights [and] a smoking cap’, Fernandez and his balloon began to ascend without incident, but soon began rapidly losing altitude as he crossed nearby Gibson Island. ‘Just as it was about to sink behind the trees out of view, the parachute was seen to expand,’ recounted a newspaper report. ‘A moment later ... the balloon shot up again with the parachute attached but without the aeronaut.’

Assuming the worst, the Alice was immediately dispatched to rescue the professor. As it happened, Fernandez – realising his balloon was going nowhere – took himself close to the ground and dropped safely from the trapeze and into the mud.

Accidents, floods and a murder

The good times, however, were not to last. In 1891, an elderly man died after falling off the switchback railway. In 1892, a notable murder occurred near the aquarium, resulting in 17 year-old perpetrator Francis Horrocks becoming the youngest person ever executed in Queensland. Two years later came the horrific accidental death of 9 year-old Bessie Smith, whose head was crushed between the Woolwich steamer and Queensport wharf.

In March 1892, a large storm blew the switchback railway and some empty cages into the river, and less than a year later the Great Flood of Brisbane ran through the Aquarium grounds, knocking down fences and freeing animals.

In the aftermath of the flood, the Natone was discovered in the middle of a swamp in Eagle Farm, some 80 yards from the shore, jammed against the remnants of a wrecked cottage. A week later the Aquarium Company offered the steamer to the newly-formed Joint Bridges and Ferries Board, set up to reestablish means of travel across the Brisbane River after the Great Flood. The Woolwich was sold a few days later.

The steamer Natone, a long way from home. This photographer, according to a newspaper report, was able to capture this view by clambering to the top of a four bedroom house that had also washed away, and was lying on its side in the Eagle Farm Flats.

Amazingly, the Aquarium reopened on Easter Monday 1893, and the Natone and Alice continued to ferry visitors, although the site now offered much less in the way of animal attractions, relying mostly on dances and concerts, pleasure boat cruises and picnics. As late as December 1896, the Aquarium was advertising its attractions, including “free hot water”. Newspaper reports suggest the crowds still came to the site, although it appears the company was making enquiries into new revenue streams, including rowing races and cycling meets.

It was clear, however, that the public’s love affair with the amusement park was over. On 8 November 1897, the aquarium was sold. The main building continued to operate as a dance hall until 1901 – and was even briefly considered as the location for a plague hospital – but before long the Queensport Aquarium was all but forgotten.

The ruins, from The Week, Friday 19 January 1917

Today, the former site sits at the end of Aquarium Avenue in Hemmant, and its memory is commemorated with signage in the nearby Queensport Rocks Park.

Many thanks to Russell Turner from Bulimba District Historical Society for his generous research assistance with this blog.

Resources

- Gateway Bridge, Strikhedonia website, accessed 22 August 2025

- Hemmant State School 1864-1989 : a history of the school and its community, 1989, compiler Gil Perrin, John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland.

- A Look Back at the History of the Queensport Aquarium in Hemmant, Morningside News website, accessed 22 August 2025

- Lost Amusement Parks of SEQ - Part 1: Brisbane and Surrounds, IBIS Channel 32 (YouTube) website, accessed 22 August 2025

- The pretty little spot behind Queensland's first theme park, Brisbane Times website, accessed 22 August 2025

- Pugh's Almanac, Brisbane, 1862–1899, Qld. : Theophilus P. Pugh, John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland

- Queensport Aquarium: Dreamworld of the 1880s, The Community Leader website, accessed 22 August 2025

- QUEENSLAND FLOOD SUMMARY 1890 - 1899, Bureau of Meteorology website, accessed 22 August 2025

- Queensport Rocks Park - Walk Along The Gateway Bridge, Weekend Notes website, accessed 22 August 2025

- Tigers, Roller-Coasters and Special Effects: Brisbane’s 19th-Century ‘Dreamworld’, Christopher Dawson website, accessed 22 August 2025

- National Library of Australia, Trove, trove.nla.gov.au, accessed 22 August 2025

Comments

Your email address will not be published.

We welcome relevant, respectful comments.