Guest blogger: Elaine Acworth - 2018 Q ANZAC 100 Fellow.

In July 1943 the forces of the Imperial Japanese Army were slowly being beaten back along the Kokoda Track, and displaced from their strongholds on the north coast of New Guinea. As the war moved northwards, General Douglas MacArthur, Supreme Commander South-West Pacific Area, moved his headquarters from Melbourne to Brisbane, basically taking up residence in Lennons Hotel in Queen Street. With him came his general staff, of course, and also his not-so-general team – Central Bureau – the inter-allied ULTRA-secret signals intelligence organisation he had caused to be formed the previous year. They were tasked with the interception, decoding and analysis of secure enemy transmissions in the South-West Pacific and, by September, they’d taken up residence at 21 Henry St, Ascot – Nyrambla.

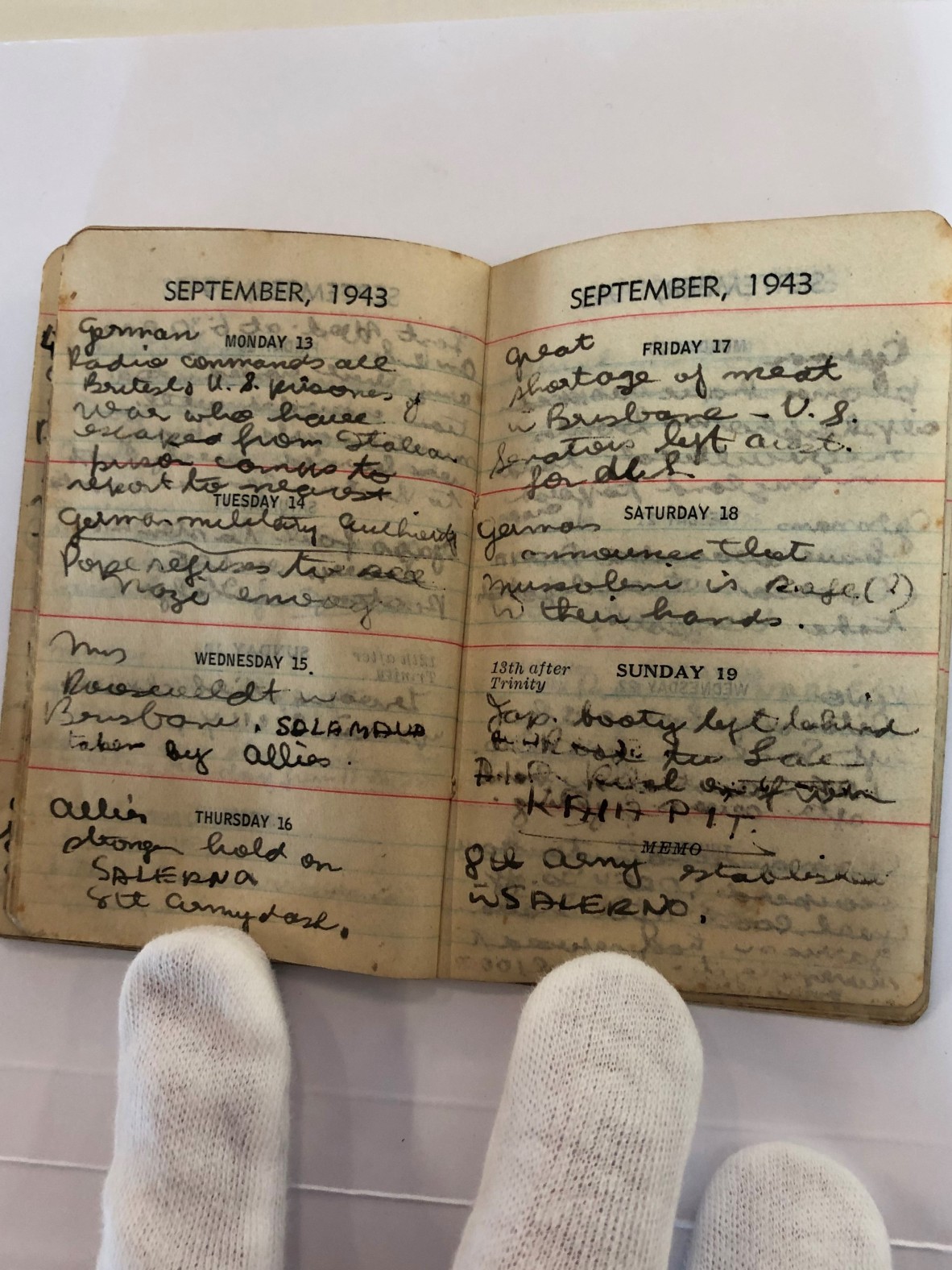

The enormous panic of an imminent mainland invasion of Australia by Japanese forces had quietened, but we were still a country at war – every enterprise was geared to supporting the war effort – austerity marches and drives were held, war bonds were issued – "100,000 smackers to smack the Japs!", factories were refitted for war construction, armies of Civil Construction Corps men created roads, rails, port facilities, army camps that had not been there 18 months before, Manpower relocated men and women not in designated essential services to work around the country. Rationing grew tighter – 6g of butter per person per day, desperate meat shortages in Brisbane – hundreds queuing outside butchers, a new handkerchief cost a whole cotton ration token and a half, would you believe?

And I know this because Joan Peeters told me so.

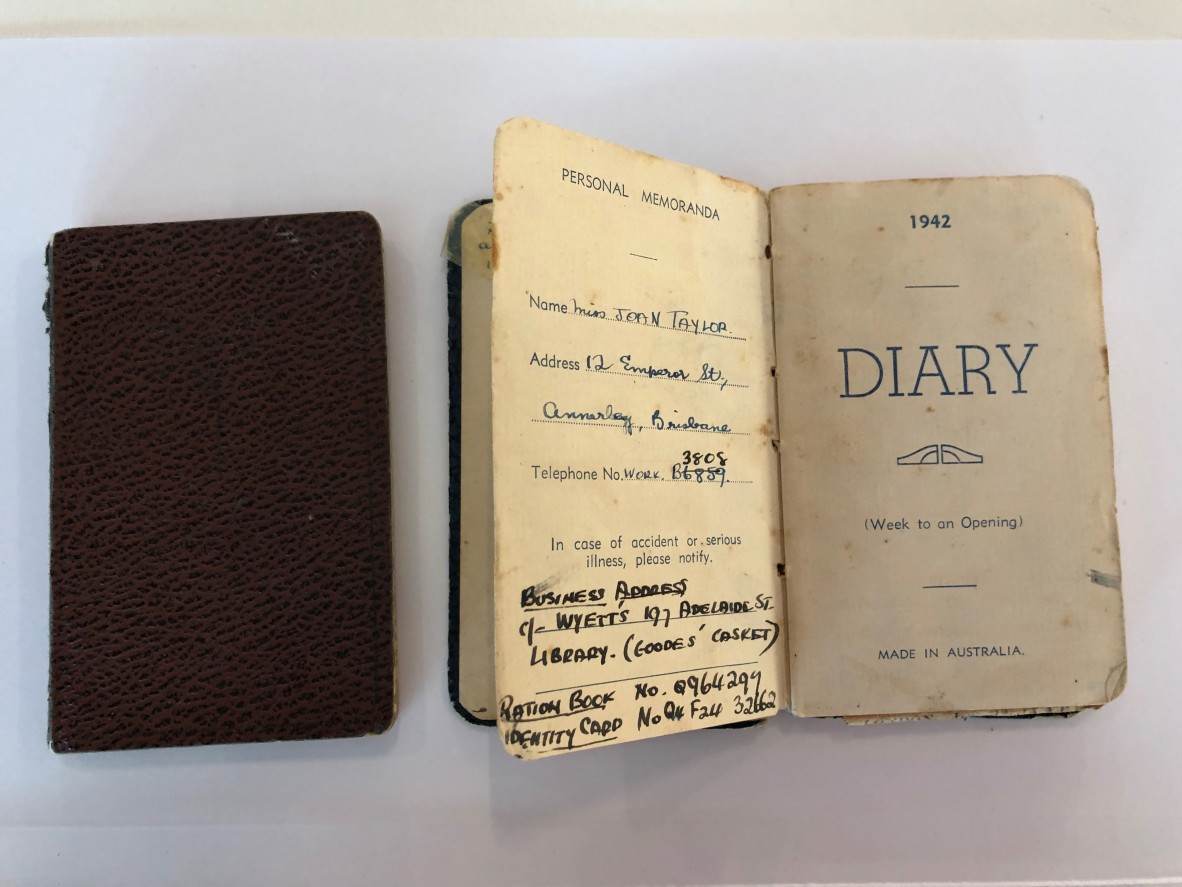

7129 Joan Peeters Diaries 1941-1944. John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland

Joan Peeters – nee Taylor – was a young nurse at the General Brisbane Hospital from 1941 to 1944 and she told me all of that. She kept war diaries for each of those years – tiny, leather-bound books that she could slip into a skirt pocket, this big …

She didn’t note personal events – she noted the events of the war. So these diaries became a kind of intimate timeline – one person’s understanding of what was happening in the world around them. It was Joan’s diaries that told me that:

- on May 1st "Jap subs were off the east coast and threatened sea lanes with America",

- on the 4th the Brisbane Line enquiry made headlines and "strikes threatened US war output",

- on the 5th "238 typhoid cases were reported in Melbourne" and "280 people were rounded up in Sydney restaurants – socialites caught in Manpower’s net…"

- on the 14th "Japs sank the marked hospital ship, Centaur" – "all but 30 of the men and 1 nursing sister (Sister Savage) drowned" and 16 patients were brought to Joan’s hospital – "admitted at about 2 am to ward 9".

And all the while the Northern perimeter of the country was still under attack – air-raids on Darwin and Townsville and the North, Japanese submarines sinking shipping along the eastern and western seaboards – midget submarines in Sydney Harbour the previous year, and, with the sinking of the Centaur off Fraser Island, demands to "avenge the nurses!".

Australia and Australians were at risk – and the country knew it. Desperately unprepared to sustain itself on a wartime footing in 1939, and with most of its fighting men in European or African/Middle Eastern theatres of war until 1942, the country felt its vulnerability – and this was especially so in Queensland as accusations of the ‘Brisbane Line’ were made by a Labor Minister against the former Menzies government and repeated and repeated – and not at first denied by PM Curtin, though Menzies refuted it.

So, all of this forms and informs the world of the drama – I am writing an audio theatre piece set in Brisbane in 1943 – following a week in the life of a young AWAS signalwoman, Claire Graham, who intercepted coded enemy messages.

I created a Sydney home base for her and had her transferred to Brisbane, where she’s stationed at Kalinga – a major interception station.

Her mother (of course) is panicked by any potential threat to her oldest chick, at one point in a brief telephone conversation saying…

"How are you, darling? Are you alright? The newsreel had columns of tanks being hauled through Brisbane – that’s not you, Is it? You’re not near there?"

And later,

"Claire, can’t you get posted back down here? This Brisbane Line business has me very wound up – I don’t want you up there if the government is proposing to abandon half the country to the Japs –"

And when both her children remonstrate that this isn’t so, the government would never do this – Curtin says he won’t do it, she replies,

"Well, he says that now, dear! But needs must where the devil drives – they’re still right on the doorstep –"

Geoffrey Ballard in On Ultra Secret Service, his memoirs of working at Central Bureau, notes the variety of political opinion within the organisation but, on this subject, the idea of the Brisbane Line, the general dismay at the idea that Australians should abandon any part of their country – that the Australian fighting man should welsh on the fight – this was completely unacceptable – a cause of great swearing and anger.

(As you probably know, the August ’43 federal election saw Curtin and Labor win by a landslide. There is no more talk of the Brisbane Line.)

Anyway, as a result of all of this, young Australian women filled roles traditionally ascribed to men, and joined the Armed Forces or their Auxiliary Services in their tens of thousands.

Amongst those young women were members of the AWAS (Australian Women's Army Service) who trained as signallers and interceptors at Bonegilla in Victoria and became Kana interceptors for Central Bureau at a variety of locations, including Kalinga Camp from 1943. There were WAAAF (Women's Auxiliary Australian Air Force) interceptors for Central Bureau, as well – but the first of these were stationed primarily in North Queensland – Townsville’s No.1 Wireless Unit (Roseneath) and they weren’t physically relocated to Central Bureau in Brisbane until 1944.

Which didn’t suit my storyline at all.

Not because there was anything wrong with the young women or their work or the stories they could tell – I just needed them to have been in Brisbane in 1943.

Why?

Because drama is about sub-text and con-text. It’s about setting up a series of apparently completely opposed or irreconcilable circumstances. It’s about how people operate then. How they manoeuvre, compromise, negotiate – or not. How they realise themselves, for good or ill.

So – why 1943?

Because in '43 the mainland would still have felt threatened.

But also, by '43, these interceptors were experienced, practiced, they knew their job and were confident in what they knew. Jean Hillier’s memoir, No Medals in this Unit, speaks of being able to identify a familiar operator by his ‘fist’, his particular sending style and quirks.

This was going to be an important ability for my main character.

At one point, early in the play, we hear an internal monologue from Claire. She is dialing through frequencies, looking for a Japanese signaller who has just switched frequency – something they did often to make interception harder:

She says, "… come on, come back to Claire… I’m not saying it out loud, of course I’m not, not any of it – just thinking it: well not really thinking it, more a kind of mental reaching out into the dark…"

And then she finds him –

"There you are… There’s nothing else, only this, only him and me, across thousands of miles. It’s Dancin’ Man. I know his hand on the key and he’s crazy-quick, jive-feet quick, and he thinks he’s alone, talking to one of his own – and he is… just not only that…"

Also, by 1943, experienced operators were able to pick up and identify certain phrases, place names, call signs. Geoffrey Ballard, Jean Hillier and Doug Pyle – all CB’ers – have all attested to this in their published memoirs. Certain call signs were found on the same frequencies again and again, and identified. So, if that call sign was used – you knew what unit was sending, and the D/F (Direction Finding) teams would establish their approximate location.

Then, suddenly, in traffic analysis, you knew who was where – and once the message was decoded – you knew what they were saying. This was terrifyingly exciting and effective and huge in impact.

So, I’ve made my young women recognise those words – requests for repeats of the information, mentions of the word, ‘danger’ or ‘attack’, the code sequence for query – ‘what?’ whose dot and dash pattern made the sound: ink Emma ink. And some unit call signs and some place names.

So, my plot involves a young AWAS interceptor, stationed at Kalinga Base now –

who intercepts a series of messages that lead her to infer that a Japanese submarine may be somewhere close-by, off the Eastern seaboard…

very close-by, indeed.

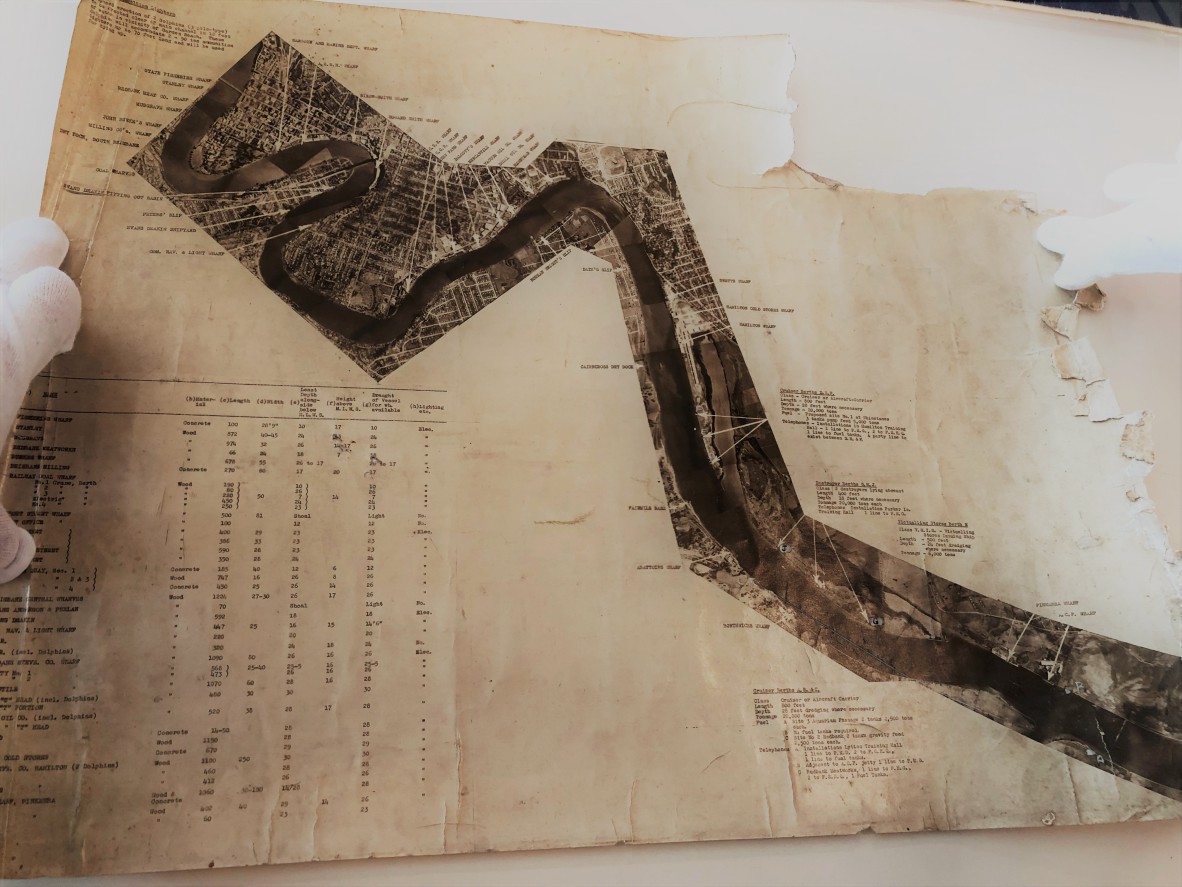

So in considering this, I spoke with some sailors who advised that I needed to see historical charts. The Bay and the river were very different, now to then.

I found some wonderful maps in the State Library's maps cabinets –

US Army maps of Brisbane during the Second World War – but a broken sequence – so I can’t see the whole part of the river mouth I need.

Aerial photo map of the Brisbane River, ca 1941:

28320, Aerial photo map of the Brisbane River, John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland

And I’m comparing them to a navigational map hand-drawn by E.F. D’Arth in 1929 – he was a master who needed to navigate up the Brisbane River to the meatworks at Redbank and left detailed notes in his hand-drawn map – which side to stay on and when to turn or change. This river map definitely shows all of the islands at the river’s mouth as islands still, and many creek inlets in what is now built out as Brisbane airport. Moreover, the Bay had anti-submarine defences installed – and I’m currently waiting on some maps of these from the Australian War Memorial…

So – there’s a way to go yet. I’ve written a very rough first draft – which tells me all the things I don’t know – and points me in the directions I need to go to follow up.

Further reading from Elaine Acworth

Comments

Your email address will not be published.

We welcome relevant, respectful comments.