A prickly problem : Dr Jean White-Haney and the prickly pear

By Simon Miller, Library Technician, State Library of Queensland | 27 November 2012

Prickly pear is the common name for several species of the genus Opuntia that are native to the Americas. Prickly pears arrived in Australia with the First Fleet in 1788, picked up as cuttings in Rio de Janeiro. Governor Arthur Phillip had decided to import the plants as the basis for a possible cochineal industry. Cochineal is a red dye made from the bodies of the cochineal scale insect that lives on one variety of prickly pear. Over the succeeding decades other varieties of prickly pear were imported and the plant was used for hedges.

Leaves of the prickly pear cactus plant at Clermont,1986. Ron Gale. 7435 Ron and Ngaire Gale Collection. John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland, Image 606-08-20

The plants were taken from Sydney to Scone in the Hunter Valley and from there to the Darling Downs in the early 1840s. The hard-coated seeds of the prickly pear were spread by native birds and browsing cattle who ate its fruit and fragments of the plant spread by floods along riverbanks would take root wherever they landed. Up until the 1870s the plant was generally regarded as a useful addition to the local flora and an emergency stock fodder in times of drought.

By the 1870's the rapid spread of the pear was beginning to cause some alarm. In 1872 a petition was presented to parliament calling for a prohibition on the use of prickly pear for hedges but others were advocating for more widespread use of the plant and extolling its value. It would take several more decades before the Queensland government would take any direct action against prickly pear. The Crown Lands Act of 1895 was the first Queensland statute to mention prickly pear and this was merely to provide some incentives for lease holders to clear the pear from land they held.

Prickly pear Dulacca, 1910. John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland. Negative number: 200492

Over the first decades of the twentieth century the rate of spread of the prickly pear increased dramatically until, at the peak of infestation, some 250,000 square kilometers were rendered useless. Arthur Temple Clerk published a pamphlet on The prickly pear problem in Queensland in 1913 in which he dramatically describes the scale of the problem.

Undoubtedly no part of the World has ever had or even now possesses such a soil affliction to contend against, as this State has in that most terrible and most appalling gigantic 'octopus' Prickly Pear, which has already with its huge and rapid far reaching feelers got possession of fully 30,000,000 acres of this grand and most magnificent State's richest and closer settlement lands. Yes, so marvellously and with such rapidity has it spread (and is still spreading) that it is almost, if not quite beyond realization. But, alas, it is only too true, and if not checked by some quick and huge method, then this great State's closer-settlement lands, practically as a whole will be doomed.

In 1912 the Queensland government established an experimental station in the heart of prickly pear country at Dulacca under the direction of a full time scientist. The biologist chosen to establish and run this experimental station was Dr. Jean White. Dr. White was only the second woman to be awarded a doctorate of science in Australia and this was the first ever scientific appointment of a woman by an Australian government.

Dr. Jean White and staff at the Dulacca research station, ca 1913. John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland. Negative number: 200496

Dr. Jean White, or Jean White-Haney as she was known after her marriage, was born Rose Ethel Janet White in 1877 at Melbourne Observatory. Her father was astronomer and meteorologist Edward John White. She was educated at Presbyterian Ladies' College and the University of Melbourne, being awarded her doctorate in 1909. She was elected a member of the Royal Society of Victoria in 1908.

In an article in The Register News-Pictorial of 1929 she recalls the experience at the little railway siding of Dulacca, now a small town between Miles and Roma on the Warrego Highway.

"It was in the midst of the thickest pear -a desolate little place where living was primitive. I was young then, and still rather nervous, but I insisted on not being given any special privileges because of being a woman. If you do that, you make it harder for all women to engage in research. The inevitable response to any suggestion that a woman should be sent out on field work is, 'But she couldn't live alone out there.' Failures of women who cannot rough it would naturally be magnified.

"I lived in the little public house there, and worked on my fascinating job with all the enthusiasm of those who see small beginnings to great ends. The methods chosen for experiment were the introduction of suitable insects and poison."

Queensland Prickly Pear Boards research station, Dulacca, ca.1913. John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland. Negative number: 200493

In the course of her work she met American-born agricultural chemist Victor Haney and they were married in 1915. Unusually for the time Dr. White-Haney was able to continue her work at the experimental station after her marriage.

"We lived in two little tents," said Dr. Haney, "with floors and walls as high as the back of a chair, and finished off with hessian. Since then I have lived in all kinds of huts and tents, and can make my home anywhere, though I love the luxury of city life.”

World War One put an end to the experimental work as it became impossible to get research workers or supplies of poisons for testing but by 1929 the war against the prickly pear had been all but won.

"Work is still proceeding on those lines, and it has been most wonderfully successful. I have seen lately areas which used to be quite impenetrable, where you could not have walked except on the top of the pear — and for miles you can see nothing but dead pear.

"Two insects are mainly responsible, the cochineal and cacta blastus, and of these the cacta blastus is the more spectacular, and gets most of the credit. But they are a great team!

"Poisoning is also used, but poisoning alone would never clear Queensland. It is far too expensive except, to clear special areas; but useful for killing off pear that sprouts again after ravages by the insects, and also for use together with insects. Insects are rather spasmodic. Usually, in special areas,Queensland has an army of men working inwards systematically with poison, while the insects work outwards, missing some patches.”

Dr. White-Haney had success against one species of tree cactus (Opuntia monacantha) prevalent in North Queensland using cochineal insects (Coccus indicus) and, although this insect was not effective against the most prevalent species of pear, this success encouraged the continuing search for biological controls that led eventually to the introduction of the Cactoblastis cactorum moth that eventually brought the pest under control. So successful was this insect in destroying the prickly pear scourge that it is the only insect to have a memorial hall dedicated to it, the Boonarga Cactoblastis Memorial Hall near Chinchilla.

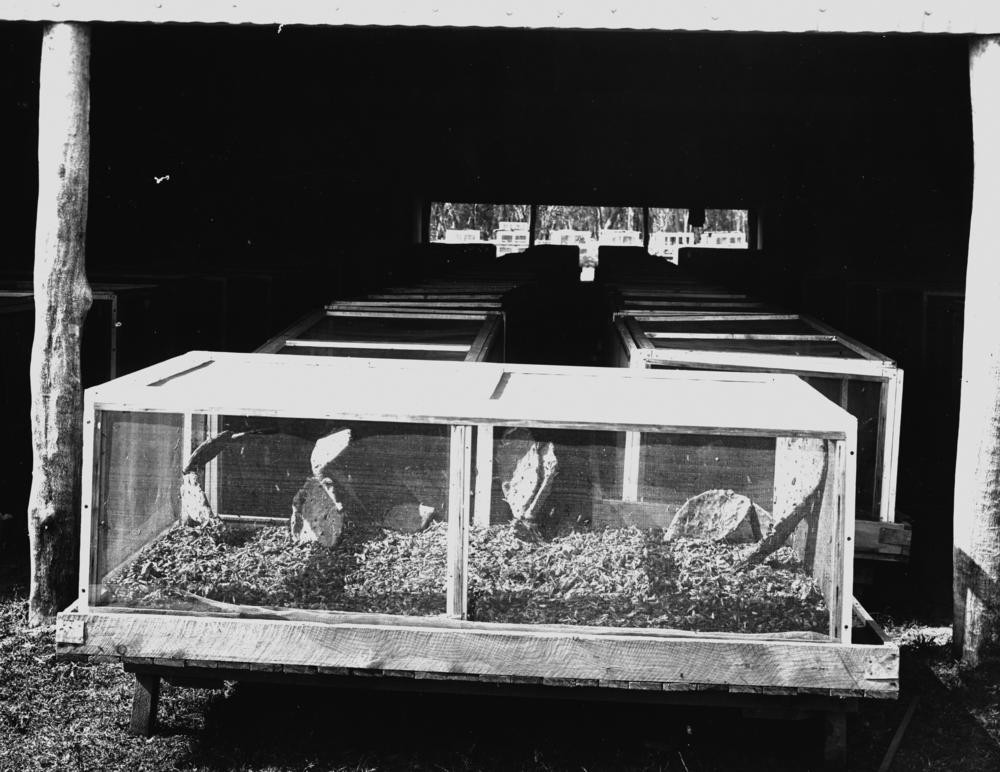

Cactoblastis cages at the Bug Farm, Chinchilla, Queensland, ca. 1930. Western Downs Regional Council. Image chi00099

The importance of the eventual victory over the pear is summed up in an article reprinted from Geographical Review, October 1992 Prickly pear menace in eastern Australia 1880-1940 by Donald B. Freeman.

Prickly pear infestation delayed by more than fifty years settlement of large areas of eastern Australia. After elimination of the pest, close agricultural settlement began energetically. By 1940, ten million hectares, formerly dense prickly pear-covered country, had been selected for settlement, and the revenue of Queensland was boosted by income from beef, cotton, grain, and dairy products. On already settled land that had suffered only moderately from prickly pear infestation, agricultural productivity also increased dramatically. At Chinchilla, production of dairy products surged sevenfold from 400,000 pounds in 1926 to 3,100,000 pounds in 1939.

Harvesting the first crop of wheat on land reclaimed from Prickly Pear infestation Chinchilla 1933. State Library of Queensland, Image API-101-01-0006

Jean White-Haney lived for a short time in Western Queensland before moving to Brisbane. She was a founding member of the Lyceum Club with stints as secretary and president. After a break from scientific work to raise her two sons she returned to research to study the pasture weed, Noogoora burr, that was causing major problems for the wool industry and also studied pasture grasses at Glen Innes in New South Wales. In 1930 she gave up research and joined her husband, who had returned to the United States. She died in 1953.

The John Oxley Library holds the reports from the Prickly Pear Expermental Station, Dulacca for 1914, 1915 and 1916.

Simon Miller – Library Technician, State Library of Queensland

Comments

Your email address will not be published.

We welcome relevant, respectful comments.