The Petrie family

By Annabelle Tonkin, Collection Curation and Engagement | 9 April 2024

Who were the Petrie family, and why should we know their story?

The Moreton Bay area and beyond were changed forever after their arrival in 1837, with tangible markers still evident today in the form of placenames and heritage listed buildings. Uniting convict, architectural, political, social, and First Nations histories, their dynastic legacy begins with pioneer and patriarch, Andrew Petrie.

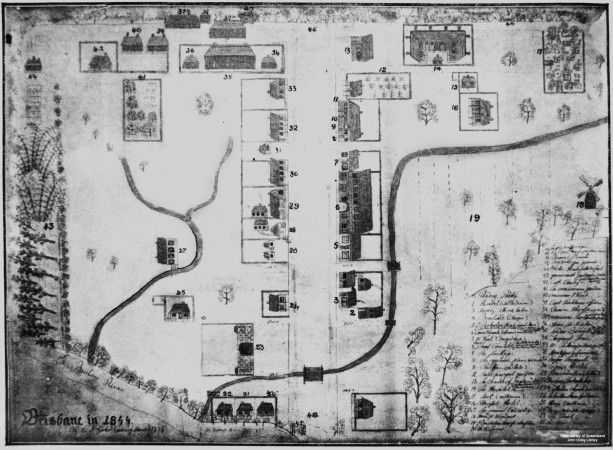

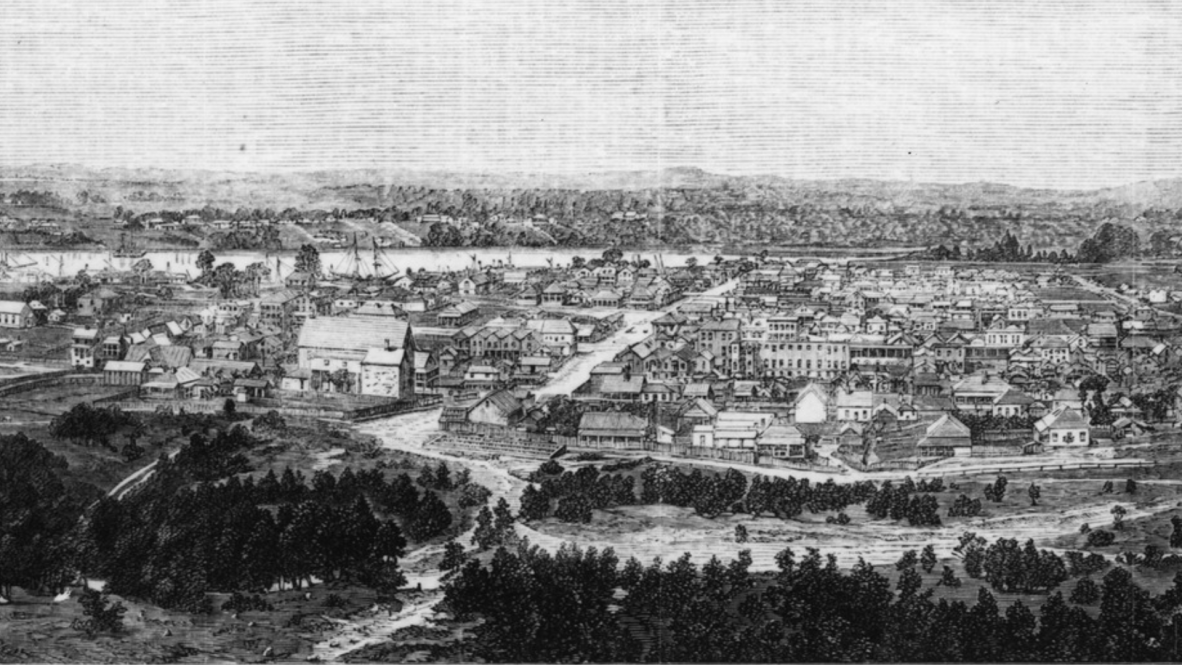

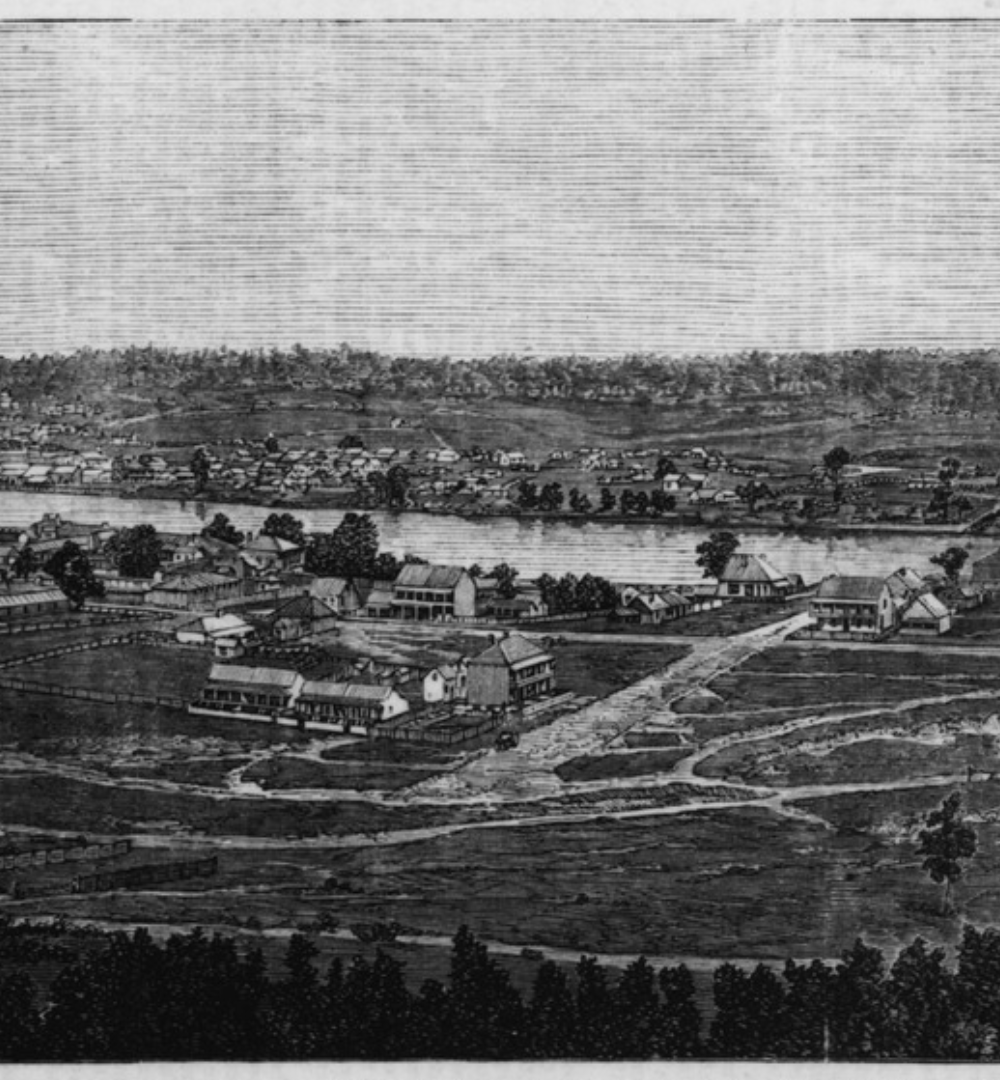

Brisbane in 1865 - featuring the Normal School (shown prominently just left of centre) built by the Petrie firm in 1861 on the corner of Adelaide and Edward Streets.

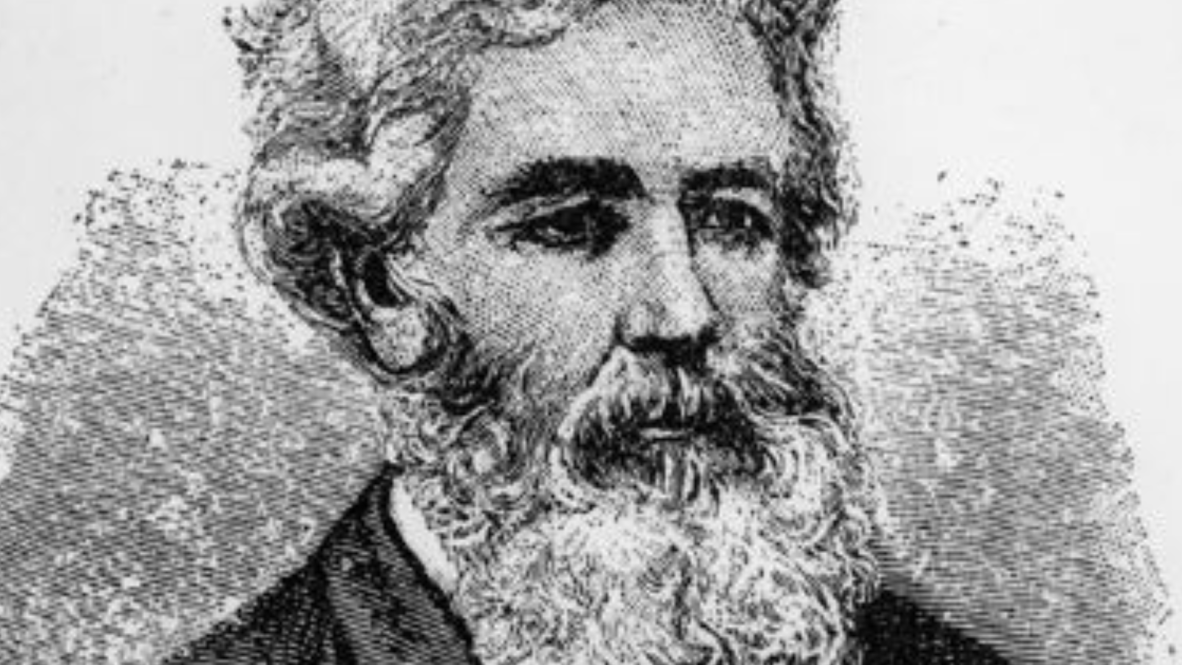

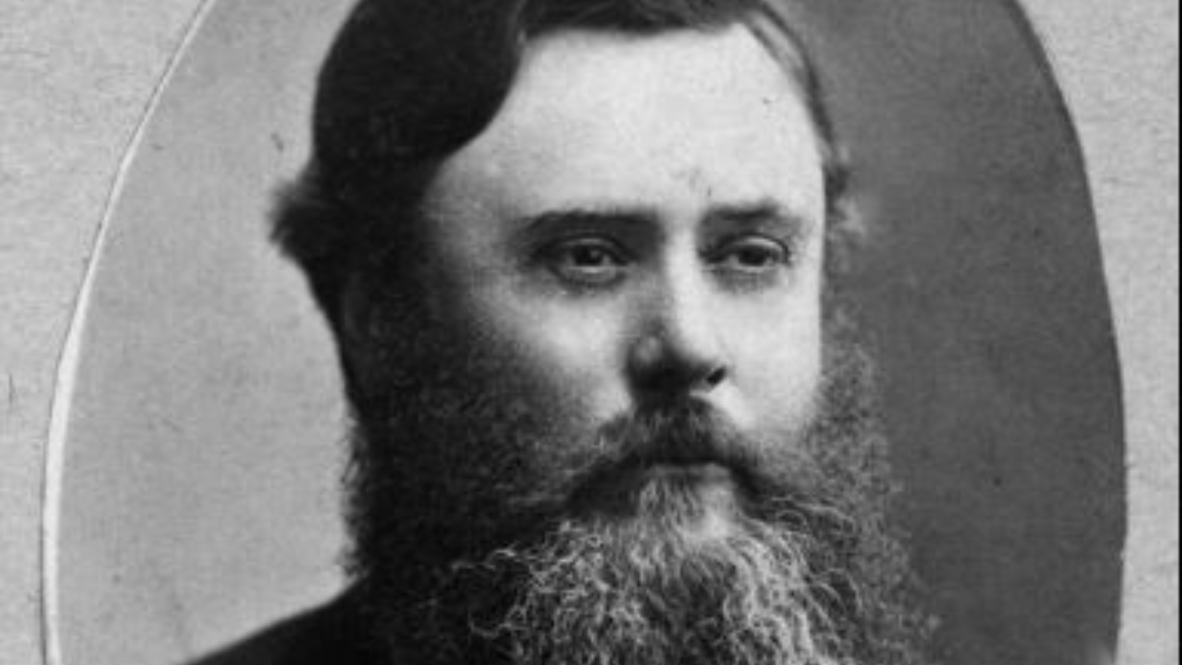

Andrew Petrie (1798 - 1872)

Andrew Petrie, the patriarch of Brisbane’s first free settling family, was a highly skilled craftsman known for his humanitarian leadership and determined work-ethic.

Born in Scotland in 1798, Andrew was raised as a staunch Presbyterian in a working-class family, training as a carpenter, mechanic, stone mason, and architect.

He is often credited as Brisbane's 'founding father'.

Detail of Andrew Petrie, date and artist unknown. John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland, Negative no. 62151

In 1831, Andrew was one of 52 skilled tradesmen recruited by Reverend Dr John Dunmore Lang to emigrate to Sydney as free settlers. Lang intended for these individuals to assist in his aims to establish Presbyterian schools, places of worship, and values within the growing colony. Aboard the Stirling Castle, and accompanied by their families, many of these workers spent the long journey further developing their skills and building relationships with each other.

Once in Australia, Andrew worked on major infrastructure projects, first for Lang, then in a private partnership with another Stirling Castle immigrant George Ferguson, before taking the governmental position of clerk in the Commissariat Department. During his time working in Sydney Andrew built a trusted rapport with Colonial Engineer, Major George Barney, who managed civil construction and defence works. In 1837, Andrew took up a position as Superintendent of Works in the Moreton Bay Penal Colony after being recommended by Barney.

The Petrie family moved with Andrew to Moreton Bay, sailing north on the Scottish made James Watt, the first coastal steamer to enter the region. At this time, the settlement was comprised of nine basic buildings built from convict labour, with most of Andrew’s work concerned with repairing existing structures, such as the old windmill, and supervising convicts in their work.

Andrew’s appointment signified that a transition to open settlement was imminent, and in the years preceding the disestablishment of the penal colony, he spent time exploring Moreton Bay and beyond, surveying areas and making note of what resources could be used as potential building materials.

In 1842, when the area was declared open for free settlement, Andrew’s contract ended and provided him with a choice – return to Sydney or remain in newly founded Brisbane. The Petrie family stayed and became Brisbane’s first free settlers, with Andrew establishing his own business of construction and architectural enterprise.

It is his work in this capacity that earned him the title as Brisbane’s ‘founding father’, as he not only dominated much of the early construction of the settlement, but his knowledge of the area, resources and creation of materials gave him a position of authority.

Andrew contracted sandy blight in 1848, prompting him to pass management of the family business over to eldest son John. Despite his blindness, Andrew remained an active figure of the settlement industrially and socially until his death in 1872. Andrew’s obituary in the Brisbane Courier described him as follows:

“As a father, he was kind and indulgent; as an employer, he was respected, though strict and watchful; and as a friend and companion he was genial and hearty – nothing pleasing him better than a chat about old times”

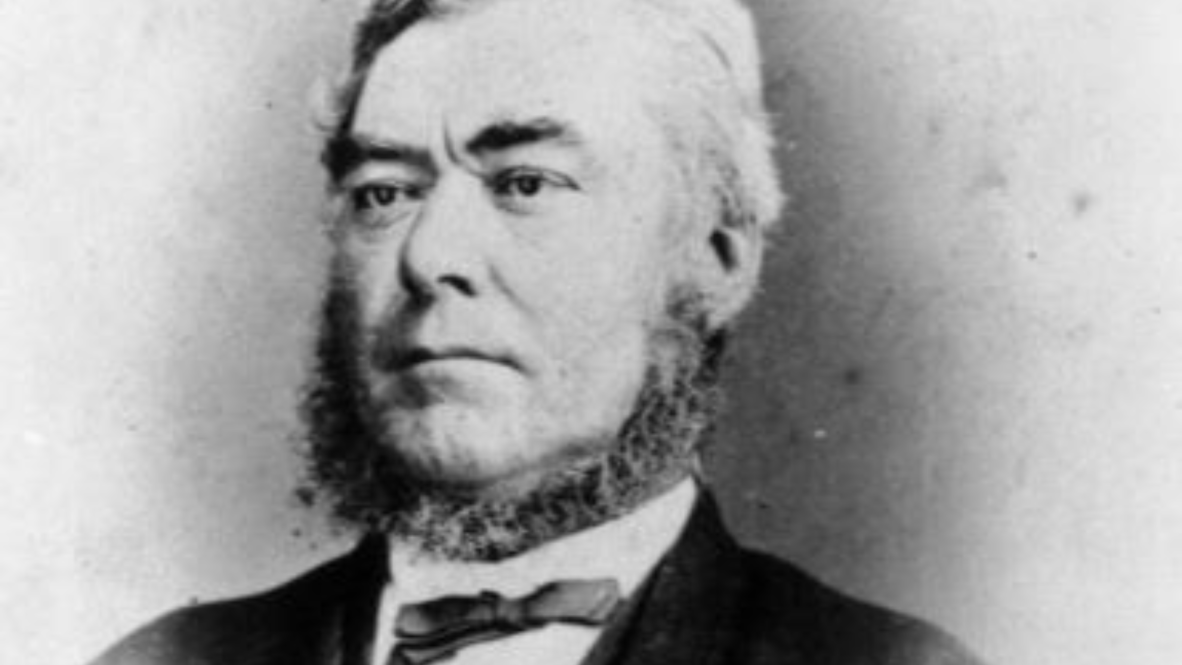

John Petrie (1822 - 1892)

Detail of Signed portrait of John Petrie, date and photographer unknown. John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland, Negative no. 65629

Andrew’s eldest son, John Petrie, left his own significant legacy on the growing colony in his role as Brisbane’s first Mayor and an eminent public citizen.

John took over management of the Petrie firm in 1848, sustaining their reputation for high quality workmanship and leaders in the construction field. Under his leadership, the Petrie's exerted a dominance in construction and architectural development over the growing city.

John took after his father in many ways, displaying an aptitude for construction, business acumen, and a commitment to civic duty. John was educated at Reverend Dr John Dunmore Lang’s school in Sydney, then later in Moreton Bay by his father and other workmen, John learned cabinet making and carpentry skills.

After his father contracted sandy blight in 1848, the 26-year-old John became sole proprietor of the family business, renamed John Petrie from the original, Petrie & Son. Despite Andrew’s blindness, he continued to play an active role in the business, known to work out equations and figures in his head for amounts of materials required.

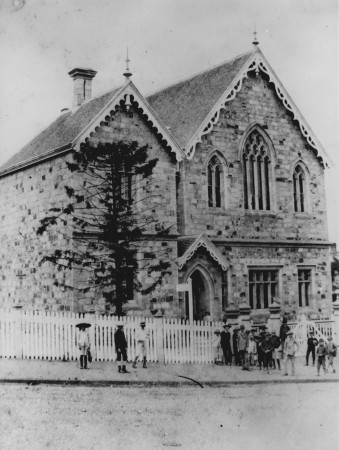

Under John’s leadership, the business and by extension, the influence the Petrie family had on the early buildings of Brisbane, expanded considerably, constructing numerous religious buildings including the first Methodist Church, Anglican Parsonage, the first Presbyterian Church, the Ipswich Presbyterian Church, and St John’s Pro-Cathedral.

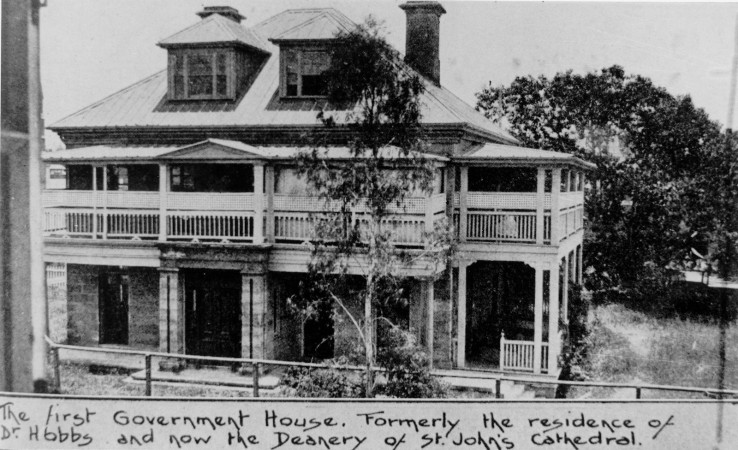

Alongside these tenders, the Petrie firm also worked on various residential, commercial and civic buildings of note, including the first Supreme Court Building, the first Customs House at Petrie Bight, Adelaide House (The Deanery), Ipswich Gaol, Adderton, and Newstead House. Under John’s leadership, the firm exerted a dominance over much of the work undertaken in the city.

In 1859, John was unanimously elected as Brisbane’s first mayor, a feat historians attribute to his popularity with the mostly working-class population, due to his success as a builder and lived experience as one of the settlement’s longest standing residents. Notable adversaries in this election included rival contractor Joshua Jeays, as well as merchants such as Patrick Mayne and Robert Cribb, who all served on Brisbane's first council.

One of the most significant demonstrations of the Petrie family’s respected status within the colony came just after this election, with the Separation of Queensland and visit of Governor Bowen.

Sir George Ferguson Bowen, first Governor of Queensland, arrived with his wife Lady Diamantina Bowen in Brisbane on 9 December 1859, marking the creation of the State of Queensland. Governor Bowen was greeted by John Petrie in municipal robes, while Isabella Petrie led a group to greet Lady Bowen. Andrew Petrie was also invited to be part of the reception committee, and it was upon the verandah of Adelaide House, a building he constructed, that the proclamation of separation was read to crowds of thousands.

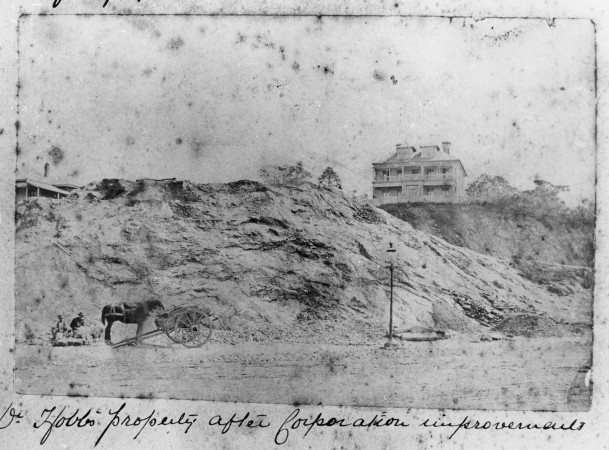

Adelaide House was originally built by Andrew Petrie for Dr William Hobbs as a residence in 1853, before being leased to the Governor as the first Government House until construction of the residence at Garden’s Point was completed.

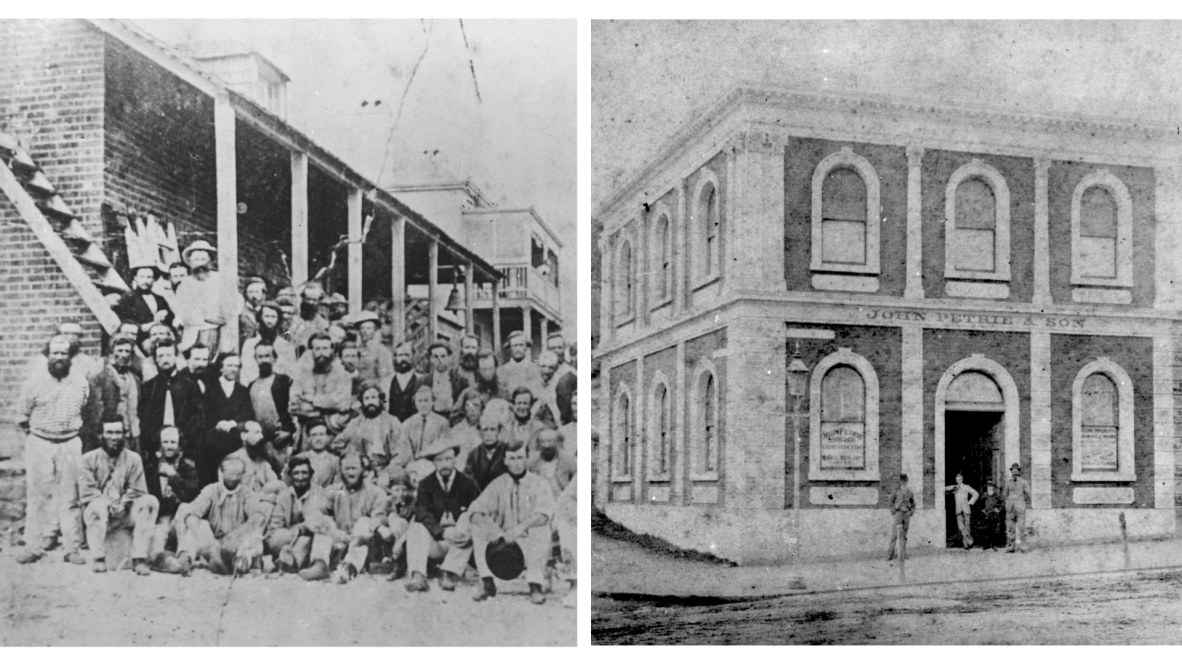

John married fellow Scottish emigrant Jane Keith, and the couple went on to have ten children – five sons and five daughters. Their eldest son, Andrew Lang Petrie, was named after long-standing friend and supporter of the Petrie family, Reverend Dr Dunmore Lang. John worked alongside Andrew Lang, and eventually brought him into the business, which was renamed again as John Petrie & Son in the 1880’s.

Composite detail of photographs, Staff of John Petrie, building contractor, Brisbane, ca. 1867 and Premises of John Petrie & Son, Brisbane, ca. 1882.

Thomas Petrie (1831 – 1910)

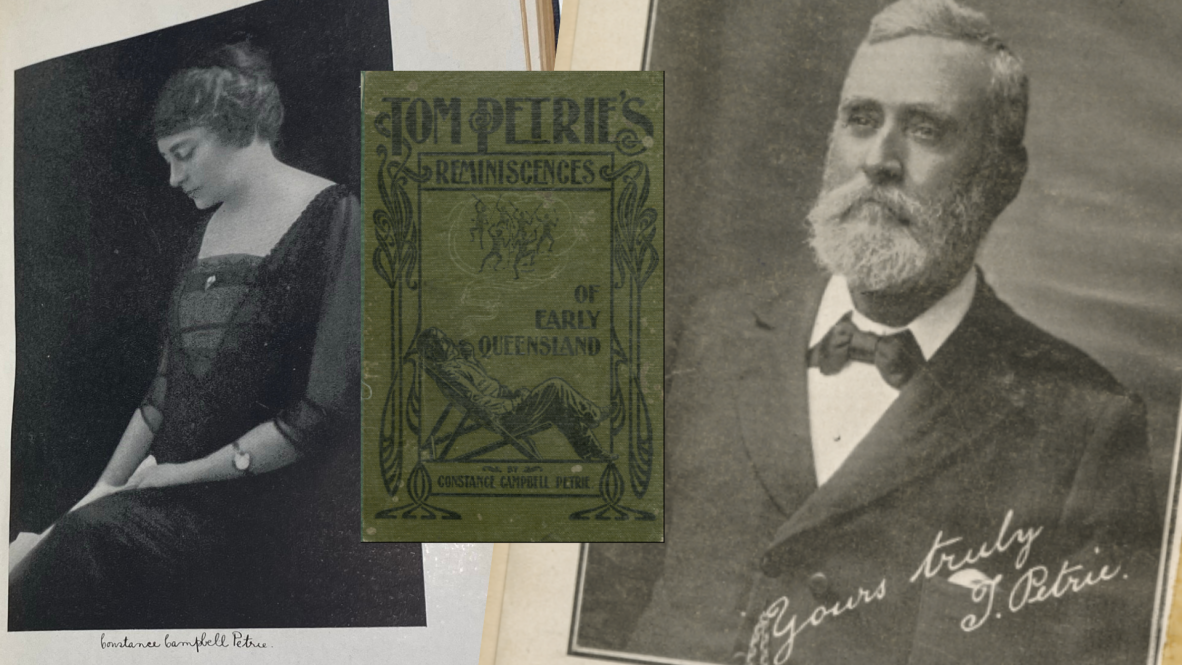

Detail of Thomas Petrie (1831-1910), date and photographer unknown. John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland, Negative no. 12939.

Thomas Petrie was only a few months old when his parents, Andrew and Mary Petrie, emigrated to Sydney in 1831. After relocating with his family to Moreton Bay in 1837, Thomas’ grew up amidst the penal colony, and later the open settlement of Brisbane. Thomas learned the Turrbal language from a young age, spending his childhood mixing freely with the traditional owners and their children.

His renown memoir, Thomas Petrie’s reminiscences of early Queensland is his most significant legacy, recorded by his daughter Constance Campbell Petrie.

Originally published as a series of articles in The Queenslander, Thomas’ reminiscences detail the settlement and exploration of colonial Queensland, particularly regarding the Petrie family, and experiences of First Nations people on the frontier and beyond.

Thomas himself was an avid explorer, journeying north of Brisbane towards the Sunshine Coast. It is in this direction he chose to settle, favouring a life on the land over construction work or politics. On recommendation from Dalapai, a distinguished First Nations elder and longtime friend of the Petrie family, Thomas established himself on over 6,400 acres near the mouth of Pine River.

Thomas’ land was named Murrumba, for its meaning of ‘good place’ in local language. He spent the rest of his life here, raising his family with wife Elizabeth and becoming involved in the timber industry. Despite high commercial value, Thomas refused to exploit Bunya pine in recognition of their significance to First Nations people in the area.

Constance Campbell Petrie describes her father’s knowledge of First Nations customs, language, and experiences as ‘intimate’ and having ‘an undoubted ethnographic value’ in the preface to the 1904 publication of Thomas Petrie’s reminiscences of early Queensland*. In his time, Thomas was recognised as an authority on local First Nations people, often used as a messenger, and an interpreter on surveying expeditions and in criminal trials.

Notable inclusions in Thomas' reminiscences are memories of warrior Dundalli’s murder, conversations with First Nations leaders about the impact of colonial expansion, and witnessing acts of kindness, generosity, retaliation, justice, trade, and violence on the frontier. Thomas also recounts his memories of Prince Alfred’s visit to Brisbane in 1868, Duramboi’s return to Brisbane, Moreton Bay’s first boat the ‘Selina’ being christened, exploration of the Sunshine Coast area, and the introduction of various buildings throughout the settlement.

Constance began recording her father’s memoirs in the early 1900’s, and published them before his death in 1910, at the age of 79. In this year, the North Pine district was renamed to Petrie in his honour.

* Language used in this publication reflects the creator’s attitude or that of the period in which they were written and is now considered inappropriate or offensive.

Photographs of Constance Campbell Petrie and Thomas Petrie shown within Tom Petrie's reminiscences of early Queensland (dating from 1837) / recorded by his daughter, 1904.

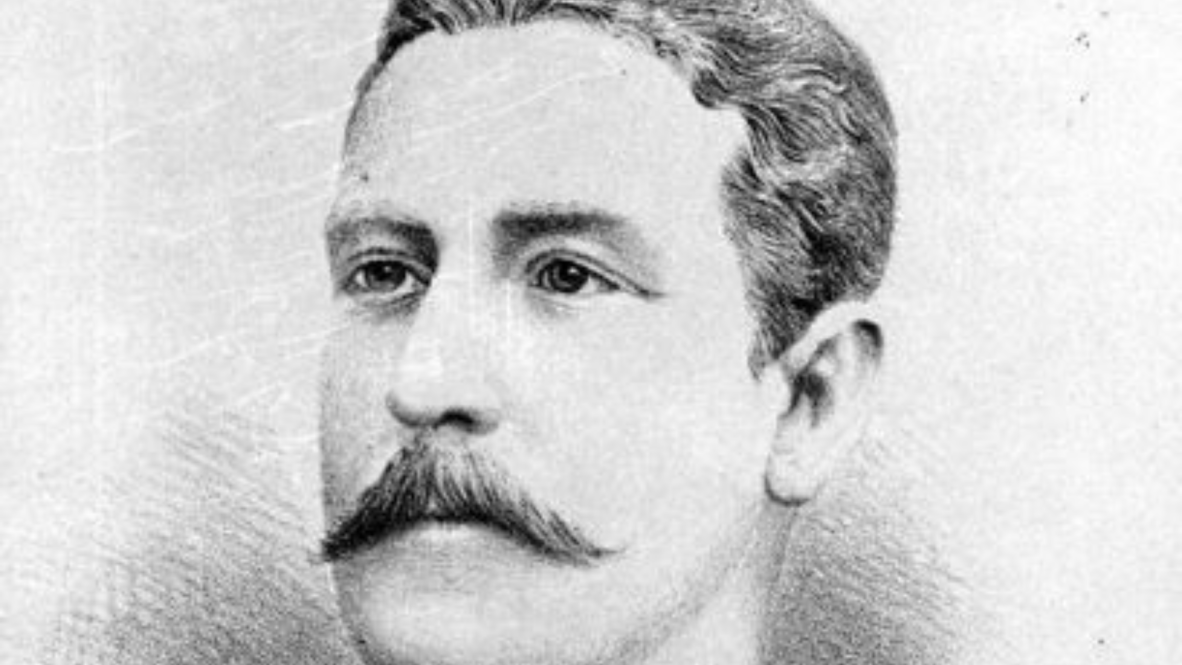

Andrew Lang Petrie (1854 – 1928)

John’s eldest son, Andrew Lang Petrie, was named after his grandfather’s friend and supporter, Reverend Dr John Dunmore Lang.

Born in Brisbane, Andrew followed in his father’s footsteps, taking on both an active role in politics and management of the family firm.

Under Andrew Lang’s leadership, the Petrie enterprise moved away from large-scale construction to survive.

Detail of Sketch of Andrew Lang Petrie, date and photographer unknown. John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland, Negative no. 167296.

Taking after his father, Andrew Lang became an active participant in civic life with his pursuit of political representation. In 1885 he was elected to the Toombul Division Board, then later in 1993 as the Member for Toombul in the Queensland Legislative Assembly.

After Andrew Lang took over proprietorship of the family firm in 1888, the business faced many challenges. It was during this time that the city’s urban growth favoured the more ready-made construction material of timber, moving away from stone masonry, which the Petrie’s had mastered and claimed as their signature. This evolution, along with John’s death in 1892 and the economic crisis of 1893, destabilised the business for a few years before it became insolvent.

As a result, Andrew had to temporarily resign from his Legislative Assembly seat while the insolvency proceedings were conducted. This didn’t stop him from being re-elected and continuing to hold the seat for many years.

In 1910, Andrew Lang rebranded the business as Andrew L. Petrie Monumental Masons, moving away from construction towards monumental masonry, brickmaking, tile-making and joinery. With assistance from his eldest son, John George ‘Jack’ Petrie, the Petrie firm continued operation, albeit on a smaller scale, at new premises in Toowong.

Andrew Lang retired from politics in 1926, and passed the family business on to John George, who would carve his own legacy in both business and sporting arenas.

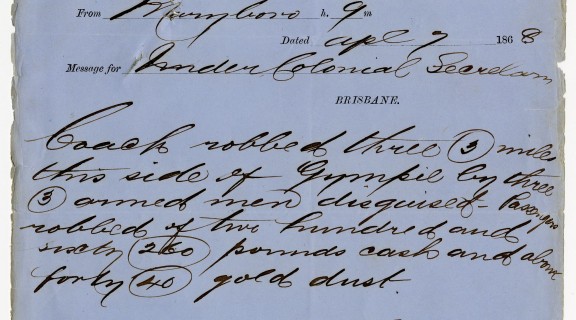

In our collection: Colonial Secretary's Correspondence

Comprised of letters received by the Colonial Secretary of the British Colony of New South Wales relating to the Moreton Bay settlement from 1822 to 1877, this collection provides invaluable insight into the establishment of the Queensland colony and the individuals who took part, such as the Petrie family.

The information contained in this correspondence provides deeper insight into who the Petrie’s were as individuals, and the realities of their experiences as Brisbane’s first free settlers.

For example, we can see that Andrew took great pride in his work and character, writing to defend both in 1838 following accusations of a conflict with a Barrack Sargeant and misuse of government resources in his lumber yard. Letters between John Petrie and the Colonial Secretary regarding the erection of structures and use of government resources demonstrate the decision-making processes inherent to the physical growth of the colonial settlement, and further correspondence in the collection provide context on relationships with First Nation’s people in the area, immigrant and convict matters, exploration, surveying, and public expenditure.

A selection of the correspondence relating to the Petrie family is listed below.

Language used in this correspondence reflects the creator’s attitude or that of the period in which they were written and is now considered inappropriate or offensive.

In Letter 19 October 1838 from Andrew Petrie and Letter 22 October 1838 from Andrew Petrie, Andrew recounts his version of events of the confrontation between himself and Barrack Sargeant Lowry, welcoming an investigation into the matter.

In Letter 1 February 1842 from John Petrie, John requests permission to obtain and employ government resources in the erection of various buildings, including residential dwellings, a carpenter and a blacksmith.

In Letter 1 July 1843 from Andrew Petrie and Memo 1 July 1843 from Andrew Petrie, Andrew forwards expenses incurred during an exploration expedition northward of Moreton Bay, with the aim of procuring plants and specimens of pine. The Memo shows details of these expenses, including payment for those who accompanied him such as his sons, and local First Nation's people.

Women in the Petrie family

While the Petrie’s legacy is overwhelmingly recognised through the men’s contributions, much of their success would not have been possible without the support, sacrifice, and contribution of the women in their lives.

In moving with her children to the penal colony of Moreton Bay in 1837, Mary Petrie (1796 – 1855) surrendered the comforts of domestic help and social company. Accommodation was scarce, forcing the family to take up residence in the Female Factory recently vacated by women prisoners, who had been pushed further outward from the settlement to discourage fraternisation. The Petrie’s lived here, in what Andrew described as “a hole”, for eighteen months, during which time Mary gave birth to her youngest child, George.

After moving to their cottage in Petrie Bight, Mary’s situation improved slightly, having access to the river which assisted in domestic duties of cleaning and laundering, as well as the ability to lean on local First Nations’ women for childcare and company.

Scholars Dimity Dornan and Denis Cryle profess that “the success of colonial families depended heavily on the unpaid labour of wives and children”. While Mary dedicated herself to mostly domestic duties, she is also remembered as a humanitarian that provided opportunities to many ex-convicts, intervened against floggings, and provided prisoners with extra rations unbeknownst to her husband, Andrew.

Of Mary and Andrew’s eight children, they had one daughter, Isabella Cuthberson Petrie (1833 – 1910) who was born in Sydney. When she was only fourteen years old, Isabella was given the honour of christening the first boat built in Moreton Bay, as the two masted vessel departed from Petrie Bight. Her christening of the ill-fated boat in 1847, the ‘Selina’, reflects the respected position of the Petrie family in those early years of open settlement. She is referred to as ‘Miss Petrie’ throughout her brother Thomas’ reminiscences, recorded by her niece Constance Campbell Petrie (1873 – 1926).

Constance’s role in the recording, writing, and publishing of her father’s memories is a significant contribution to broader social history as well as documentation of First Nations’ customs, stories, and histories in Queensland. While Constance prefaces the book with a disclaimer against attempting to chart the Queensland’s history, the reminiscences remain unmatched in terms of providing a first-person account of life in the early days of the colonial frontier. Constance cites the considerable ethnographic value of her father’s lived experience as a driver for the recording and publishing of his memoir. It is clear throughout that both Constance and her father, Thomas, hoped to dismiss and challenge many harmful stereotypes about First Nations’ people. *

Details on the experiences of the Petrie wives, mothers, daughters, and sisters are harder to find, yet invaluable to understanding the remarkable story of the Petrie family and their legacy.

* Language used in this publication reflects the creator’s attitude or that of the period in which they were written and is now considered inappropriate or offensive.

Detail of Andrew Petrie's house at the corner of Queen and Wharf Streets Brisbane ca. 1859. Andrew, Isabella, and presumably Mary are on the verandah prior to meeting Sir George Bowen.

A lasting legacy

The tangible legacy of the Petrie family can be seen throughout Brisbane and beyond, including the street and suburb named Petrie Terrace, the turn of the river named Petrie Bight, the wider area once known as North Pine, but now as Petrie, as well as the significant extant buildings worked on by the family firm.

The Petrie family firm remains in operation today, as one of the longest-running Queensland businesses remarkably managed by John Geoffrey Petrie, Andrew Petrie’s seventh generation descendant.

The Petrie family story is intrinsically linked to the establishment of Brisbane, weaving together civic achievements, urban growth, architectural landmarks, colonial exploration, and First Nations history. As the areas first free settlers, their impact remains tangible.

This blog only touches the surface of their story, which is also featured in Extraordinary stories exhibition on Level 4, at State Library of Queensland.

Sources

33054, Colonial Secretary's papers 1822-1877, John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland.

Building a City: The Architectural Legacy of the Petrie family on Brisbane, 2006. John Geoffrey Petrie.

The Petrie family : building colonial Brisbane, 1992. Dimity Dornan, Denis Cryle, Published by University of Queensland Press. Call no J 929.20994. John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland.

Tom Petrie's reminiscences of early Queensland (dating from 1837) / recorded by his daughter, 1904*. Thomas Petrie, Constance Campbell Petrie. Published by Brisbane: Watson, Ferguson. Call no RBJ 994.32 PET. John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland.

*Language used in this publication reflects the creator’s attitude or that of the period in which they were written and is now considered inappropriate or offensive.

Detail of an engraving depicting Brisbane ca.1865.

Comments

Your email address will not be published.

We welcome relevant, respectful comments.