Guest blogger - Dr Rosemary Gill - Volunteer, State Library of Queensland

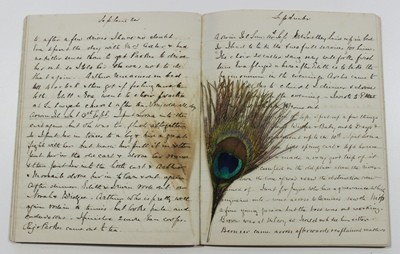

Peacock Feather - Whish Diary - OM65-33/39

The page turned, and there it was, a peacock feather as bright and lustrous as if it had been slipped in the day before. Only the sepia self-pattern, fine as a watermark, suggested its real age. For the last 121 years it had lain snugly in a hand-written journal dated to 1884. Rediscovered, it deserved the best care; and for advice I went to Gajendra Rawat, the paper conservator, at the State Library of Queensland, now the journal’s home. What he told me is fascinating. In India peacock feathers are traditional place-markers for holy texts, not least because the feathers carry a pollen-like substance that is a natural insecticide. In short, they are highly useful as well as beautiful.

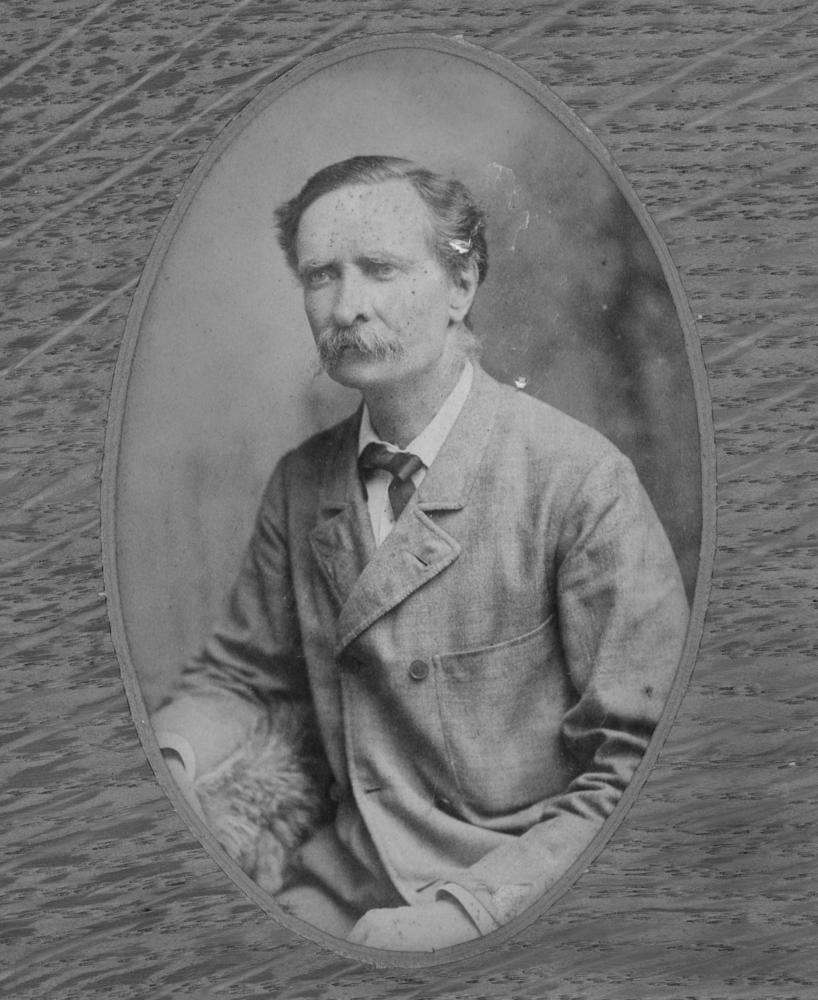

The Indian connection fits well with what we know of the journal writer, Claudius Buchanan Whish (1827-1890), who migrated to Brisbane with his wife and their two infant daughters in 1862. Captain Whish was born at Meerut, India, and held a commission in the 14th Hussars, in the Indian Army: he was ‘one of the small but influential group of gentleman immigrants … who left India after the mutiny to seek their fortunes in the newly separated tropical colony of Queensland’. (Bolton, ADB) While we cannot be sure that Whish himself slipped the peacock feather into the journal, it does, at the very least, seem feasible.

Besides being a soldier, Whish was a pioneer sugar grower (at ‘Oaklands’, on the Caboolture River), Member of the Queensland Legislative Council from 1870 - 72, one time insolvent (despite good quality sugar and rum production, ‘Oaklands’ was not a commercial success), and the Inspector of Roads Survey for the Queensland government from 1875 (as a young man in India he had been posted to the Thomason Civil Engineering College at Roorkee, north of Delhi). He was also an apparently devoted husband to Annie (née Ker), whom he called ‘Pansey’, and their four daughters and two sons.

By 1878, on a permanent public service salary, Whish could at last provide the secure, comfortable home he and Annie wanted for their children: Maud, Evelyn (‘Eva’), Ethel, Edith, Arthur and Irwin. A large, single-storey wooden building, with a shingle roof and wide verandahs, it sat on the north-eastern slope of Eildon Hill in what is now the suburb of Windsor. Whish named it Arwin Tel, a combination of the names of the two youngest children and the Arabic word for a hill; and the journals record his pleasure, and hard work, in improving the property. In 1884, for example, he built a large aviary to house birds he had bought for Irwin - red shouldered parrots, rosellas and finches; and it must have been a pretty sight, enclosing a swathe of lawn and a mulberry tree.

Whish’s journals are an engrossing record of the homely and the professional. On the domestic front, for instance, he was vigilant about his family’s health and dosed them, and himself, with terrifying homeopathic medicines like aconite and mercurius vivus as well as the ever-trusted Castor Oil. When Annie suffers a severe headache, he notes that ‘she had to take a cigarette’! Yet he is proud of the scientific advances he sees in Brisbane, such as the establishment of the Hospital for Sick Children in 1878, which received a fine new building designed by Richard Gailey in 1883. When eleven year-old Eva Hunt, daughter of family friends, is thrown by her horse and suffers a badly cut face, Whish’s record of her recovery at the Hospital gives insight into the best medical practice of the time.

His conversational style gives us lively word sketches of places and people. Some of the latter, such as the Archers, the Weinholts of Goomburrah, the Luyas, the Gores and the Chauvels, he had known in India and England. Others he met in Australia: Claud and Annie Whish were considered good company by their growing circle of friends in Brisbane and elsewhere, and both were fine singers and musicians in a society which relied considerably on drawing-room entertainment. Maud, their oldest daughter, married Reginald Roe, the Headmaster of the Brisbane Grammar School, in 1879; and the households of Arwin Tel and Winholme, the Roes’ dwelling on Leichhardt Street at Spring Hill, borrowed glass and crockery from one another for larger social events.

As the Roads Surveyor for an expanding European population, Whish travelled a great deal; and although some places like Ipswich and Toowoomba could be reached by train, other destinations lay at the end of long hours on horseback. One stretch in 1883 saw him cover about 250 km on horseback in five days’ travel. That was rounded off with a dash by train from Ipswich to Brisbane, to hear Annie and Ethel sing in a concert! Up at 5am the next day, Whish caught the 6am train back to Ipswich, and had saddled up again that afternoon.

It sounds exhausting, but Whish liked his work and was sustained by the kindness and hospitality he received from many of the station owners: John McDougall of Rosalie Plains, the McConnels of Cressbrook, the North family of Wivenhoe, the Collins of Mundoolun and Tamrookum, the Haygarths of Kooralbyn - the list of familiar Queensland places goes on, and the names associated with their colonial history.

In 1884, the year the feather apparently found its way into the journal, he travelled by the steamer Ranelagh to Rockhampton, with an overnight stop at Maryborough. We see these rapidly-growing towns through Whish’s eyes: primitive in some respects, but confident that productive hard work, plus a good public spirit, ensured a bright future. Maryborough already had a hospital, and had been able to engage the highly-qualified Henry Croker Garde as its first Resident Surgeon. Whish also noted the beauty of its Botanical Gardens, some of the first in Australia.

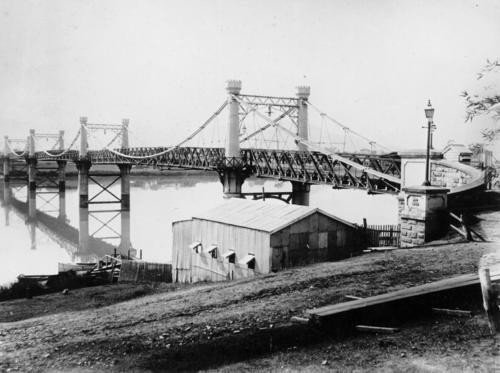

This very Victorian mix of science and entertainment, utility and ornament, is expanded in his journal entries at Rockhampton. Whish admired ‘Byerley’s Bridge’, the first to cross the Fitzroy River. An early photograph shows Frederick Byerley’s charming confection of towers and turrets, but beneath the Arthurian whimsy there was a strong structure, built for use and longevity. Whish, a devout Anglican, sought out the Church of England, and records it as ‘a fine stone edifice’. The very new School of Arts hosted an art exhibition and various other entertainments during his visit; and, here too, friends and contacts offered a welcome, especially the MacDonalds of Balnagowan in the Port Curtis district. Whish enjoyed evenings of singing, dancing, and parlour games like ‘willing’ and ‘lifting the chair’ that were popular versions of contemporary scientific research.

It comes as a shock to learn how this useful and mostly happy life ended. Claud and Annie Whish left Australia in February 1890 to make a long-anticipated visit to family and friends in England. Their ship was the RMS Quetta. On 28 February the ship struck an uncharted rock in the Torres Strait and rapidly sank, drowning 134 of the 292 people on board. A survivor told of her last sight of Captain and Mrs Whish on the steeply listing deck. Annie said to her husband, ‘Claud, you will look after me, will you not?’ He put his arm round her and said, ‘Of course, my darling.’ The vessel tipped inexorably, and they slid together into the sea. No trace was ever found of them. Their memorial is set into the wall of the Anglican church at Lutwyche, the same church at which they worshipped and where Claud Whish had been a lay preacher and synodsman. The final sentence is a quotation from 2 Samuel 1. 23: ‘They were lovely and pleasant in life, and in their death they were not divided.’

Rather as that bright feather laid down its particular pattern on Whish’s record, so his journals carry the impression of a unique life. Their historical value is considerable, and it is a privilege to be involved in their transcription.

Dr Rosemary Gill - Volunteer, State Library of Queensland

References:

Bolton, G C ‘Whish, Claudius Buchanan (1827-1890)’, The Australian Dictionary of Biography, 6, Melbourne University Press (1976).

McCallum, Beres ‘The Whishes of Windsor’, a paper presented to the Queensland Women’s Historical Society, at Miegunyah, Jordan Terrace, Bowen Hills, Brisbane, 9 August 2001.

OM65-33 Claudius Buchanan Whish Diaries 1862-1906

Comments

Your email address will not be published.

We welcome relevant, respectful comments.