Neon Nostalgia: Illuminating Brisbane's Past and Present

By Guest blogger and historian Robert Allen | 6 December 2024

Aerial view of a Gold Coast street at nightime with neon lights, 1973, John Gollings, Acc 27302 John Gollings Gold Coast Photographs, John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland. Image number: 27302-0001-0074

A new exhibition focusing on our neon sign heritage opens at the State Library of Queensland from Friday 6 December. Historian Robert Allen’s accompanying blog examines Brisbane’s role in neon’s rise, decline and recent revival.

Neon signs are an enticing blend of alchemy and art. Originating in a science lab and achieving ubiquity on main streets across the world, they came to symbolise progress and prosperity; glitz and glamour; sex and seediness.

American engineer Daniel McFarlan Moore was a pioneer of efforts to produce new light sources by electrically charging gases inside sealed glass tubes. Moore used nitrogen in his “Moore tubes” to produce a pinkish - white glow and carbon dioxide to produce a pure white light. [1] The identification of the so-called ‘noble gases’ including neon, helium, argon, xenon and krypton by Scottish chemist Sir William Ramsay in the 1890s opened up further lighting possibilities.[2] Around 1910, French inventor Georges Claude found that electrically charging neon in sealed glass tubes produced a red light and that adding mercury to neon produced a pale blue glow. Later inventors found they could make additional colours by adding phosphors to tubes containing argon and mercury.[3]

Claude’s patented neon sign technology swept Europe and then the United States, where the retail, automotive and entertainment industries harnessed it to advertise their products. In just a few years, neon signs became indelibly linked in the public mind with some of the mid - twentieth century’s most enduring literary and cinematic tropes: late night greasy spoon diners, the Las Vegas casino strip and film noir detective stories.

Claude Neon Advertisement, The Telegraph, 11 August 1932

Australians were enthusiastic early adoptors of the new technology. The Australian arm of the Claude Neon company began in the early 1920s and established branch offices in most states.[4] Based first at Barry Parade in Fortitude Valley and later at Peel Street in South Brisbane, its Queensland operation bought out smaller competitors and soon gained the lion’s share of the local sign market. [5] Early clients included Penfold’s Wines, Tritton’s department store, the Telegraph newspaper and the Tivoli Theatre.[6]

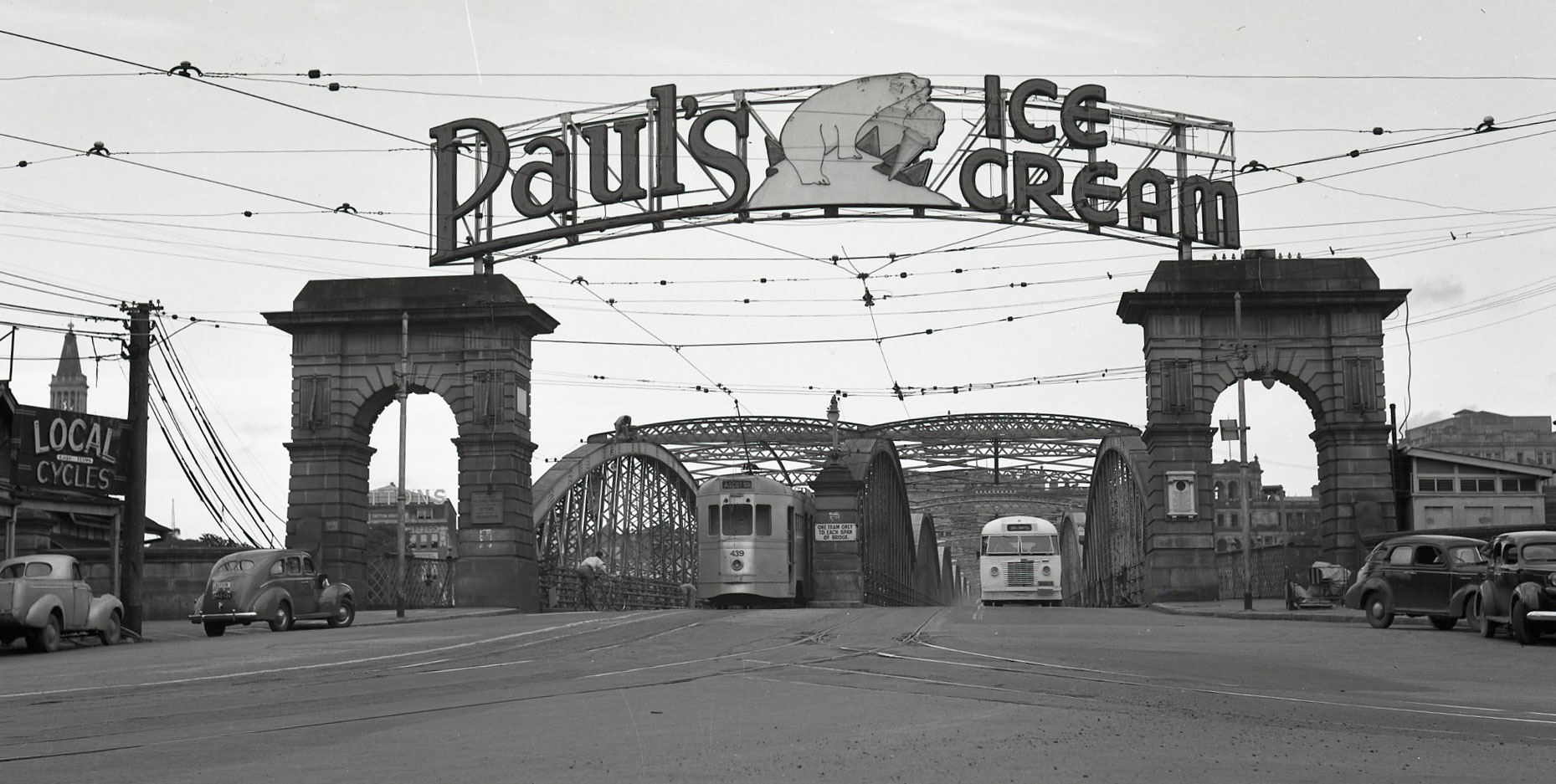

By 1932 Brisbane boasted more than a hundred neon signs.[7] During the Depression, the Brisbane City Council recognised a potential revenue stream and leased out prominent sites for neon signs, despite fears from the RACQ that they would distract motorists and cause accidents.[8] Two of the best known were the Paul’s Ice Cream polar bear and Plume Motor Oil signs on the approaches to Victoria Bridge.

In 1938 the Courier Mail noted that "Neon has transformed dull city streets to fairyland avenues." [9]

Brisbane businesses which installed neon signs between the late 1920s and the mid 1960s included the Regent, Odeon and Winter Garden theatres; the Allan and Stark, Bayards and McWhirter’s department stores; Arnott’s biscuits; Dunlop and Goodyear tyres; and cinemas and milk bars across the city and suburbs.

Some signs outside Brisbane also became famous, such as the Pink Poodle motel sign in Surfers Paradise, which was designed by Claude Neon and installed in 1967.

By then, however, neon’s dominance was under threat from newer, cheaper alternatives such as plastic and plexiglass. Neon signs were beginning to look outdated and when they broke, they often stayed broken.[10] By the late 1960s, movies such as ‘Midnight Cowboy’ and songs such as ‘The Sound of Silence’ referenced neon signs as a metaphor for social isolation and urban decay.

Neon sign for the Pink Poodle Motel, Gold Coast, 1973, John Gollings

Although ‘neon’ is still commonly used to describe all illuminated signs, most modern signs are made using Light Emitting Diodes and plastic tubes. The artisanal process has been replaced by production line manufacturing which produces a similar looking product for a fraction of the cost. There are now just a handful of craftspeople left in Australia with the knowledge and skill to make or repair an authentic neon sign.

While Brisbane’s original neon signs are long gone, some more recent examples remain, including at The Beat nightclub and Les Bubbles restaurant in Fortitude Valley; the ‘Mr Fourex’ sign on the Castlemaine Perkins Brewery in Milton; and the Griffith University sign at South Bank. Others survive in private collections.

Neon has undergone a popular revival in recent years. Some of this renewed interest is nostalgia-driven, fuelled by memories of past neon streetscapes, but a younger audience has also discovered its allure and it is increasingly used in art installations and as a decorative statement in hotels and restaurants.

Soapbox Beer sign Fortitude Valley 2021, Photo courtesy of Robert Allen

Galaxy Caravan Park Neon Sign 2024, Tanah Merah. Photo courtesy of Robert Allen.

The Gold Coast’s original Pink Poodle sign was repaired in 1987, removed when the motel was demolished in 2004 and later relocated nearby.[11] In 2015 the sign was celebrated on an Australian postage stamp.[12] More recently, the owners of the retro-themed Mysa Motel in Palm Beach installed a neon sign in a further nod to the Gold Coast’s neon tradition.

Some cities have begun to recognise and protect their neon history. Both Las Vegas in Nevada and Edmonton in Canada, for example, have outdoor museums dedicated to displaying their vintage neon art.[13]

Mysa Motel Palm Beach, 2021. Photo courtesy of Robert Allen.

Neon sign for the Surfer's Paradise Hotel, Gold Coast, 1973, John Gollings

The State Library of Queensland are to be congratulated for staging its current Neon Exhibition featuring signs made, repaired and acquired by Michael Blazek. It is worth asking what more could - indeed should - be done to preserve and celebrate our neon heritage.

[1] Technical advice provided by Michael Blazek; Dydia Delyser and Paul Greenstein, Neon: A Light History, Giant Orange Press, 2021, p. 15 and pp. 21 - 25.

[2] Nigel Saunders, Neon and the Noble Gases, Heinemann, 2003, pp. 8 - 11 and 18 - 19.

[3] Michael Blazek, op. cit., and Dydia Delyser and Paul Greenstein, op. cit.

[4] http://claudeneon.com.au/about-us/.

[5] The Catholic Advocate, 23 July 1931, the Telegraph, 12 August 1932, 4 December 1934, 16 September 1936 and 9 March 1938 and the Courier Mail, 13 November 1933, 12 August 1937 and 26 June 1939.

[6] The Telegraph, 4 September and 12 December 1931 and 2 and 10 June 1932.

[7] The Telegraph, 2 June 1932.

[8] The Brisbane Courier, February 24, 1933.

[9] The Courier Mail, 20 June 1938.

[10] Christoph Ribbat, Flickering Light: A History of Neon, Reaktion Books, 2013, p. 67.

[11] Brady Michaels and Dale Campisi, Signs of Australia: Vintage signs from the city to the outback, NewSouth, 2017, p. 11.

[12] https://australiapostcollectables.com.au/stamp-issues/signs-of-the-times.

[13] See https://www.neonmuseum.org/ and https://www.edmonton.ca/city_government/edmonton_archives/neon-sign-museum.

Comments

Your email address will not be published.

We welcome relevant, respectful comments.