Nauru : Pleasant Island to Pacific Solution

By Simon Miller, Library Technician, State Library of Queensland | 22 January 2013

Nauru is a small isolated island 3000 km North East of Queensland past Papua New Guinea and the Solomon Islands. With an area of just 21 square kilometres it is the world's smallest republic. Recently in the news for its role in the Australian government's 'Pacific solution' for refugee processing, Nauru's importance to Australia goes back much further.

The island prior to European discovery was inhabited by around 1500 Micronesian people with a distinct language and culture due to their isolation from other islands. The people were organised in 12 matrilineal clans. The island is surrounded by a reef which drops off to very deep water on the outside. The main features of the island were a fertile zone around the perimeter of the island dominated by coconut trees where all the inhabitants lived. There was a brackish lagoon fed by seepage from the ocean where the Naruans raised fish collected from the reef in palm frond enclosures. The island has a central plateau rising to 71 metres where the Naruans cultivated pandanus. Nobody lived on the plateau except during the pandanus harvest which was marked with festivities. Nauru has a tropical climate marked by very variable rainfall. Prolonged drought periods could lead to starvation. Strong ocean currents made it dangerous to venture far on the open sea and use of canoes was restricted to fishing around the reef.

Nauru was late in coming to the notice of European explorers, the first reported visit being from British merchant captain John Fearn in the ship Hunter who named it Pleasant Island. He did not land but received gifts of coconuts and fruit from the natives, who came out in canoes through the surf. The island received few visits, owing to its isolation, until the 1830s, when whaling ships began to call looking for provisions. Some European 'beachcombers' came to live on the island. These were mainly escaped convicts and other undesirable characters who stirred up trouble between the clans and who's introduction of alcohol and firearms led to a chaotic civil war that afflicted Nauru from 1878 until 1888.

In 1888 Nauru was annexed by the German Empire. The German administration sent a warship, the SMS Eber, to raise the German flag and confiscate all the firearms on the island. Some 765 firearms were handed in and more than 1000 rounds of ammunition. The Nauruans were evidently sick of the fighting and glad to get rid of their guns as long as everyone else did. The Germans banned the sale of firearms and alcohol. This was a blow for the traders on the island who made a living exchanging copra from Nauru's extensive coconut groves for guns, alcohol and tobacco. Germany was only established as a single nation in 1871 and their Chancellor, Prince Otto von Bismarck, set out to establish Germany as an imperial power by gathering colonies in those areas not already claimed by other European nations. An agreement with Britain saw the two empires divide the Western Pacific between them, the Germans taking the Caroline and Marshall Islands as well as northern New Guinea, New Britain and Bougainville. Nauru was on the German side of the border and its nearest neighbour, Ocean Island (Banaba) 300 km to the east, went to Britain.

Nauru's future was changed dramatically in 1899 when an odd rock, collected on Nauru as a souvenir and being used as a doorstop at the Sydney offices of the Pacific Islands Company, drew the attention of Albert F. Ellis, known as Bertie. Ellis was a New Zealander and a relative of John Arundel, the English founder of the Pacific Islands Company. The Company, among other interests, was in the fertilizer business and Ellis was employed as a prospector, analyst and island supervisor digging up phosphate rich deposits of guano (ancient deposits of bird droppings) on islands around the Pacific. The door stop at the company office was believed to be petrified wood but Ellis thought it looked like phosphate rock that he had seen and had a sample analysed. Everyone was astonished when it proved to be 78 % phosphate, much richer than the deposits they had been working.

At this time the fertilizer trade was undergoing a revolution. Agricultural chemists had discovered the importance of phosphorus in ecological systems and the value of soluble phosphate in unlocking plant nutrients lying dormant in the soil. This led to the development of a fertilizer industry based on the treatment of phosphate rock with sulfuric acid. In Australia's phosphate poor soils in particular the introduction of superphosphate would underpin the development of large scale agriculture, particularly of wheat growing.

Ellis was sent off to do some discrete prospecting on Nauru and nearby Ocean Island which was geographically similar, so might also have significant deposits. The situation was delicate as Ocean Island, while nominally British, had not been officially annexed and Nauru being a German territory would require difficult negotiations between with the British and German authorities. It would be important to establish the extent of the phosphate deposits without giving away their value to the Germans. Ellis found rich deposits of phosphate rock on both Ocean Island and Nauru in amounts estimated at tens of millions of tons.

On Ocean Island Ellis negotiated an 'agreement' with the natives giving the Pacific Islands Company exclusive rights to mine all the rock and alluvial phosphate on the island for a period of 999 years. The natives were to be paid fifty pounds per annum or trade to that value. The situation on Nauru required slow and difficult negotiations led by the Company's Chairman in London, Lord Stanmore. The Company was eventually reconstituted as the Pacific Phosphate Company with some German representation on the board with an agreement meaning that mining could commence in 1907 at Nauru. The native Naruans were not consulted but would be allowed a small royalty of a half-penny a ton on phosphates exported.

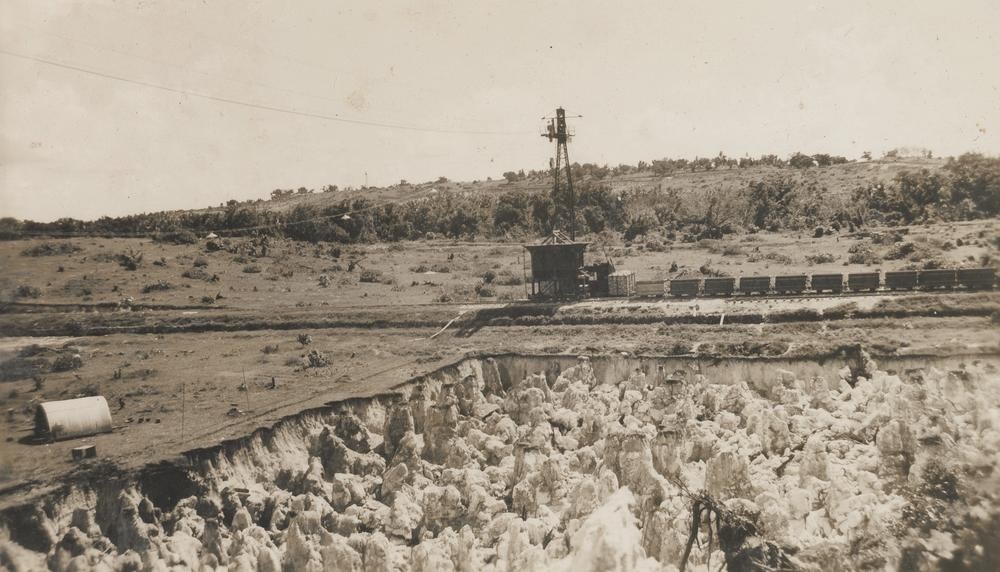

Phosphate mining on Nauru was labour intensive as the phosphate rock lay between pinnacles of limestone and had to be chipped out and hauled to the surface before being carted on tramlines to the coast. Large numbers of labourers were brought in from surrounding island groups and Chinese labour was also used. The land of the plateau was stripped of its vegetation and topsoil. Trees were valued, paid for , cut down and burnt. The viable phosphate was then gouged from between the hard coral pinnacles, leaving a waste land.

World War One led to the Germans losing their Pacific territories. The fate of Nauru was the subject of intense political maneuvering by Australia and New Zealand over who would control the phosphate that the farmers of both countries depended on. Eventually it was decided that the island would be run for the British Empire by a Commission with British, Australian and New Zealand Commissioners, who would buy out the assets of the Pacific Islands Company. Billy Hughes, the Australian Prime Minister, had lobbied strongly for Australia to have sole possession of Nauru but New Zealand were not about to let Australia have all that phosphate without a fight and Hughes had to agree to the joint Commission but secured administrative control for Australia.

Mining continued until World War Two caused a halt. In 1942 the loading facilities were bombarded by the German ship Komet. Most of the foreign workers and all but a skeleton staff were evacuated and the Japanese occupied the island. The five Europeans who had stayed behind, including the Administrator, Colonel Chalmers, were executed. The Naruans were forced to work constructing an airfield and 1200 were deported to the Japanese naval headquarters at Truk Island. Only 732 survived to be repatriated after the war. The 49 inmates of the leprosy station were put in an old boat which was towed off the coast and sunk.

After the war the United Nations established a trusteeship to govern Nauru with Australia, New Zealand and Great Britain as trustees. The business of the Phosphate Commission would continue and Australian and New Zealand farmers would continue to be supplied with cheap superphosphate. This arrangement continued until 1968 when Nauru was granted independence. Little was done to prepare the Nauruans for independence. The Phosphate Commissioners and the Australian authorities were certain that the Nauruans would agree to be resettled on another island or in Australia. The Banabans from Ocean Island had been resettled on Rabi Island in Fiji. Most of the people had been deported by the Japanese during the occupation to Nauru and other islands and their home had been devastated by mining, drought and war. Most Banabans continue to live on Rabi Island but some hundreds have returned to Banaba. The indigenous Fijian community that formerly lived on Rabi was moved to Taveuni after the island was purchased by the Banabans. Bananba and Rabi Islands are in a politically complicated position. Although the Banabans on Rabi are citizens of Fiji, the Rabi Islanders still hold Kiribati passports, remain the legal landowners of Banaba, and send one representative to the Kiribati parliament, and the Rabi Council municipally administers their original homeland of Banaba which is part of Kiribati.

The Nauruans had no intention of being resettled, however. They were determined to assert their ownership of Nauru and the valuable phosphates that covered it. In 1967, the people of Nauru purchased the assets of the British Phosphate Commissioners, and in June 1970 control passed to the locally owned Nauru Phosphate Corporation. Nauru became self-governing in January 1966, and following a two-year constitutional convention it became independent in 1968 under founding president Hammer DeRoburt.

The people of Nauru had been poorly prepared for self government by their Australian, New Zealand and British trustees who had been much more concerned with maintaining supplies of cheap fertilizer for their farmers than the long term welfare of the Nauruan people. The Nauruans were particularly vulnerable in dealing with the financial management of the wealth generated from phosphate mining. During the 1970s Nauru had the highest per capita income in the world but the Nauruans were repeatedly cheated and badly advised and much of the money that should have ensured their welfare after the phosphate ran out has been lost. During the 1990s the Nauruan government tried to set the island up as a tax haven to generate an alternative source of income but Nauru became identified as a hot spot for money laundering and sanctions from the international banking community forced them to abandon their efforts.

Nauru's main phosphate deposits were exhausted in 2002 and although there may be secondary deposits of up to 20 million tonnes, the viability of mining these deposits depends on the highly volatile market for phosphates. 80% of the island's surface area has been stripped and is unusable for agriculture or housing. After a legal settlement the Australian government agreed to provide $100 million towards rehabilitation of the island's environment. Nauru has no significant tourist industry and little in the way of fishing industry or food production. It is dependent on a desalination plant for nearly all of its fresh water needs. Nauru does derive significant income from issuing fishing licences to foreign fishing vessels but is heavily dependent on aid. The unemployment rate in Nauru is close to 90% and the Nauruan people have significant health problems with very high rates of obesity due to their diet of imported, processed food with corresponding high rates of diabetes and heart disease.

In 2001, the MV Tampa, a Norwegian ship that had rescued 438 refugees from a stranded 20-metre-long boat and was seeking to dock in Australia, was diverted to Nauru as part of the Pacific Solution. Nauru operated a detention centre for these refugees in exchange for Australian aid. By November 2005, only two refugees remained on Nauru from those first sent there in 2001. The Australian government sent further groups of asylum-seekers to Nauru in late 2006 and early 2007. The refugee centre was closed in 2008. In August 2012 the Australian government re-adopted the Pacific Solution and has since re-opened the refugee centre in Nauru.

The John Oxley Library collections are focused on Queensland but the Content Strategy also allows for collection of material about the areas contiguous to Queensland that are relevant to Queensland’s development including Papua New Guinea and the Pacific islands. The State Library holds significant resources relating to Nauru:

Ocean Island and Nauru : their story by Albert F. Ellis. The story of the discovery of phosphate on Ocean Island and Nauru written by New Zealander Albert Ellis who made the initial phosphate discoveries and was later the Phosphate Commissioner for New Zealand. Published in 1935.

Island exiles by Jemima Garrett, former ABC South Pacific correspondent. The story of Nauru under Japanese occupation 1942-1945 based on interviews with 14 Nauruans as well as diaries and accounts from the time.

Nauru 1888-1900 by Wilhelm Fabricius. An account of the German colonial period of Nauru's history based on transcriptions of original documents. In German and English.

The Phosphateers : a history of The British Phosphate Commissioners and the Christmas Island Phosphate Commission. An in depth record of the work of the Phosphate Commissioners over a period of sixty years.

Paradise for sale : a parable of nature by Carl N. McDaniel and John M. Gowdy. A study of Nauru's history as a microcosm of the problems arising from the human relationship with nature.

Phosphate, wealth & health in Nauru : a study of lifestyle change by Helen J. Rubinstein and Paul Zimmet. A study of the effects of Nauru's history on the health of the Nauruan population.

The library also holds an album of photographs taken during World War II.

Comments

Your email address will not be published.

We welcome relevant, respectful comments.