The Last Pot – the remarkable story of Brisbane’s 'beer famine' and the Milton brewery strike

By Chris Currie | 16 September 2024

Mr J. Hayes, President of the Queensland Branch of the Federated Liquor Trades Union (FLTUQ); his handwritten account of the 1937 'stay in' strike; and 'an expressive sign on an empty beer keg in a city hotel'.

For 30 days in 1937, world news took a back seat in Brisbane, as residents were glued to headlines warning of the fate of The River City's beer supply – an impending ‘Beer Famine’.

The story began on Wednesday September 15, 1937, when around 100 employees of the Milton Castlemaine Perkins brewery began a ‘stay in’ strike on the packing room floor, refusing to move from the site until management met their demands of a limit on working hours and an increase in pay.

State Library holds in its collections a fascinating handwritten account of the beginning of the strike, penned during the eventful month by brewery worker, strike spokesperson and President of the Queensland Branch of the Federated Liquor Trades Union (FLTUQ) James 'Jimmy' Hayes.

Alongside this, State Library's collections hold hundreds of archived news reports of the time, mapping the public's thirst for this remarkable story.

The first two written pages from Jimmy Hayes' account of the 1937 stay in strike.

Physical jerks and The Eagle's Nest: the Milton strike begins ...

According to Hayes, the strike was declared on ‘the grounds of altering the working hours from 44 to 40 hours a week with 8/- rise in wages, bringing it up to £5, with £5.50 for cold cellar work, and a limit of four hours a week overtime.’

‘From the start, we were invaded by Press reporters,’ he writes. ‘The Japan Chinese War was forgotten for the time being, as the people of Brisbane were concerned only in the Beer Strike, and how long the beer would last in the hotels.’

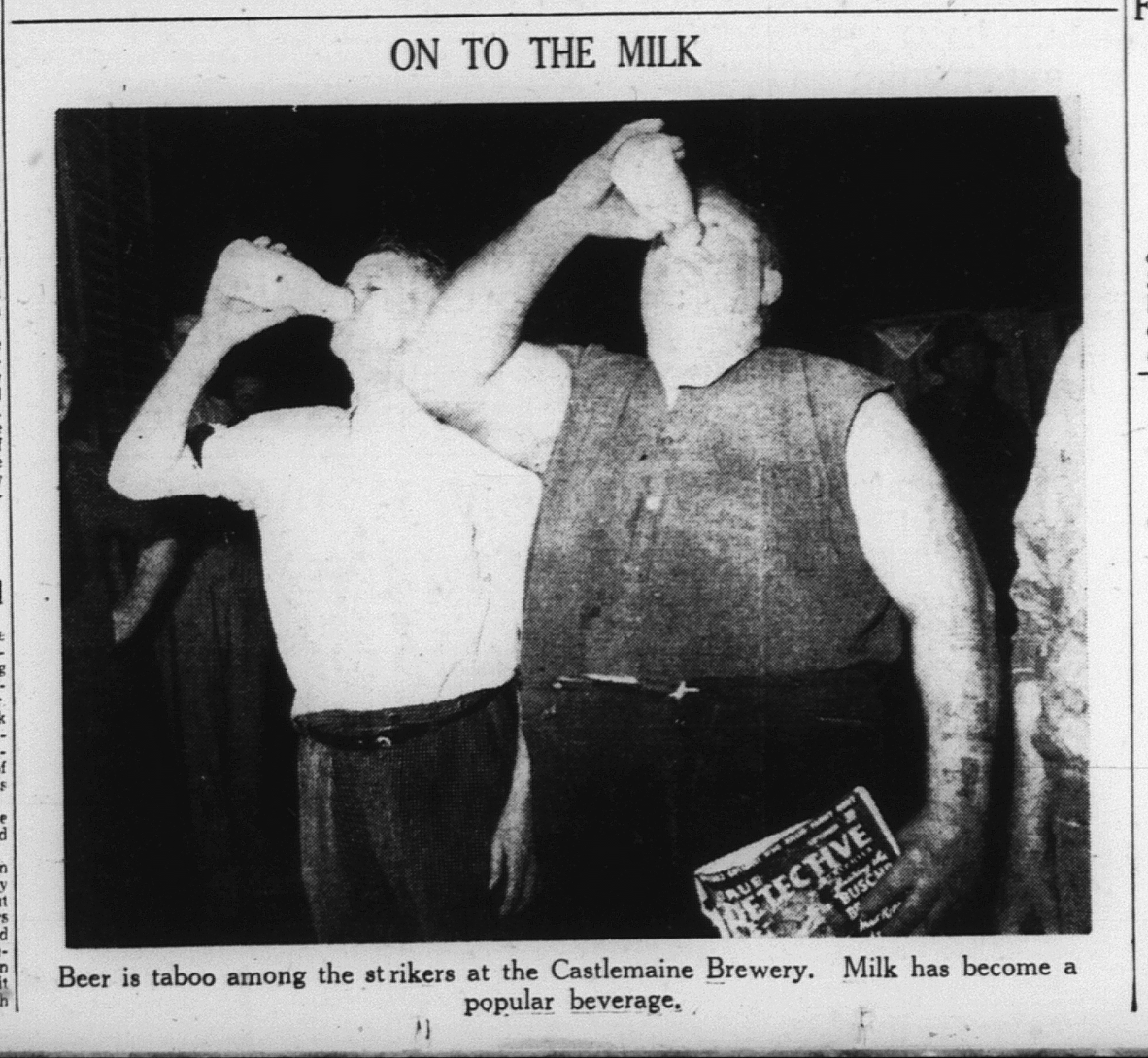

The striking men, who were ‘surrounded by 3000 bottles of beer, but ... determined not to open one of them’, settled in for the long haul – ‘making beds out of bags of bottles and bales of straw’, and setting up two copper boilers in a makeshift galley (having the luck of two men with professional cooking experience in their striking cohort).

The striking men slept soundly ...

... and kept their energy up.

Soft sand was laid on the brewery floor, the better to participate in regular physical culture classes (consisting of ‘half an hour of strenuous physical jerks’), table tennis, quoits, cards and cricket matches.

The striking men, aged from 18 to over 60, declared their sleeping situation ‘very comfortable’, with groups of strikers making use of various spaces, including “The Eagle’s Nest”, a sleeping quarter 15 feet off the ground, complete with makeshift letter box marked “Air Mail”.

The only complaints came from those maintaining the overnight picket, who reported the snoring of their comrades becoming so loud that ‘even the mosquitoes fled in panic’. Hayes reports the 'violent snores' of one particular man emitted ‘terrible thunderous concussions, which sounded for all the world like the bombing of a town during the war.’

Final draught: the beer famine begins

Things were not so relaxed at the Brisbane Brewers’ Association, comprising Castlemaine Perkins and Fortitude Valley's Queensland Brewing – more popularly known as Bulimba Brewery (whose workers were necessarily compelled to not distribute beer while the strike remained active at Milton). The Association filed to cancel the Brewery Employees’ award and the registration of the Queensland branch of the Federated Liquor Trade Union. A hearing was set for Monday 20 September.

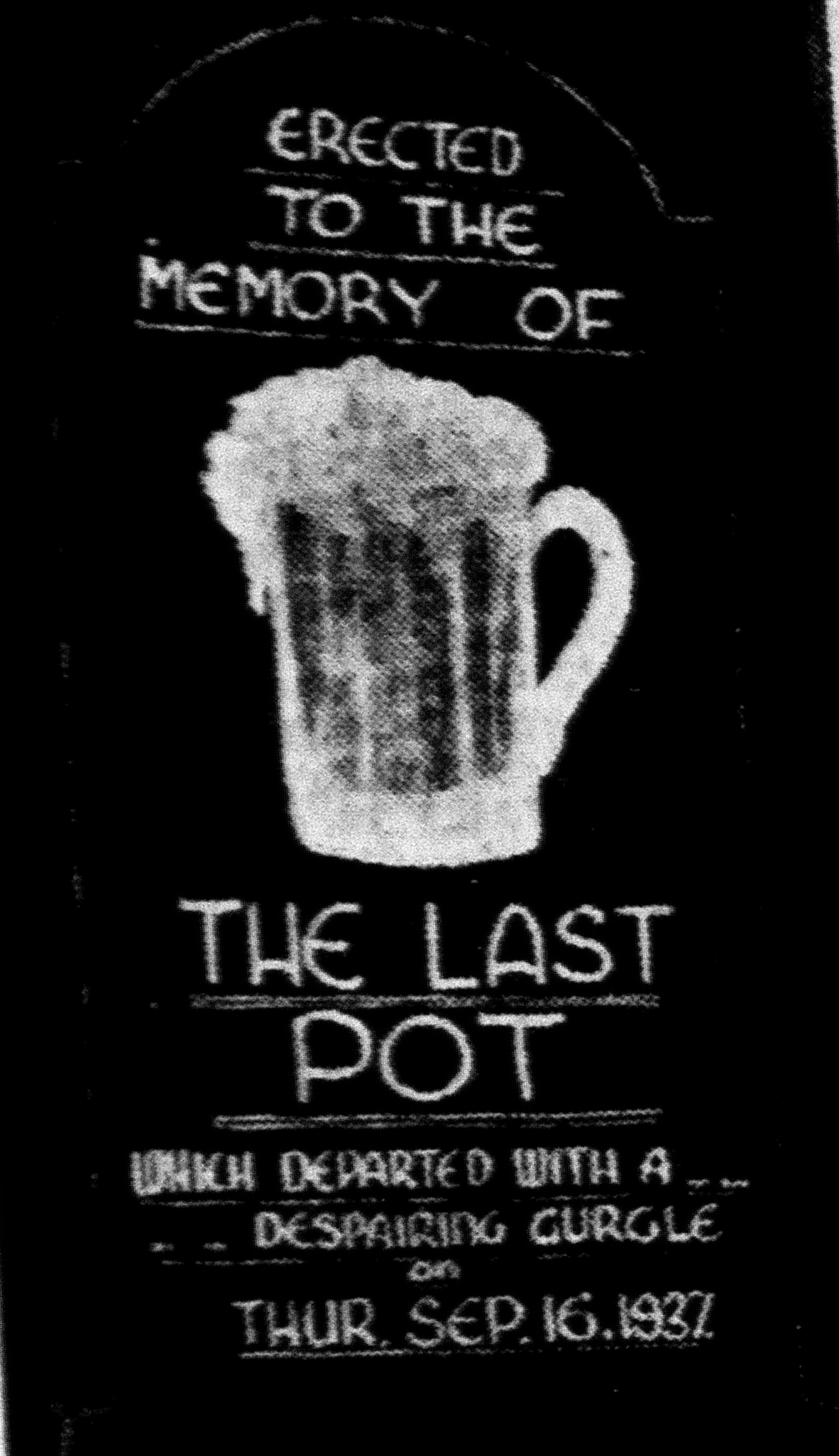

Local hotels – many of which were owned by the 2 companies – were already running out of draught beer and dipping into bottled reserves. By the first Sunday of the strike, even these bottles were reportedly being rationed to thirsty customers only in ‘short sixpenny glasses’.

While legal wheels began to turn, a steady stream of visitors made their way to the Milton brewery. Spouses, partners, supporters and family of the striking men delivered food, fresh clothes and razors alongside doses of affection.

For every heartwarming story – a baby held tight by its grandfather as though the parting and reunion had occupied months instead of hours (‘He wouldn’t go to sleep until he’d seen his grandpa’) – there were others of definite equanimity.

'During the evenings, the wives of the men and the sweethearts of the single men came out to the Brewery bringing cakes and food with them,' writes Hayes. Many good people donated books and papers which were very much appreciated by all. One chap very kindly donated a “Radio Receiver” which kept us informed with the happenings of the outside world.'

An expressive sign on an empty beer keg in a Brisbane city hotel, 17 September, 1937

Mrs W O’Keefe, interviewed by a reporter for The Telegraph outside the brewery gate, stated: 'Am I doing any cooking for Bill? No jolly fear. I'm letting the unions supply the food. I'm having a holiday — it'll do me. Nothing to cook, nothing to do, except listen to the radio. Do I miss him? Of course I miss him, but I can always come and see him. What more do you want?'

'"Go out and see my wife at West End," said Mr. Jim Hayes, the strikers' spokesperson.' And so The Telegraph reporters did.

On the fourth day of the strike, it was reported, courtesy of Castlemaine Perkins head brewer Mr A.K. Hall, that 4 brewers and 2 foremen had continued work at the brewery, aiming to save the £35,000 of beer in the process of fermenting.

‘I think it is more important that the shareholders of the company and the public should know this than the strikers had a comfortable night,’ stated Mr Hall.

By this time, both professional cooks in the striking cohort had set up a new galley in the packing room, and ‘were donned in milky white full-sized aprons and chef’s caps’.

By Sunday, beer in Brisbane hotels was virtually non-existent, with Ipswich and Gladstone nearing the same fate. Although some attempts were made to import beer from Toowoomba, unions made it clear this beer would be considered “black”.

An Industrial Court hearing the next day declared the brewery strike illegal and cancelled the Federated Liquor Trade Union Employees’ Award, Queensland Branch, so far as it applied to breweries in Brisbane. The decision was to take effect from 9 am Wednesday 22 September, unless work resumed at Milton brewery.

On 23 September, the Trades and Labour Council decided all affiliated unions were to support the brewery strikers ‘actively and financially’.

Wake-up call: the strikers dig in

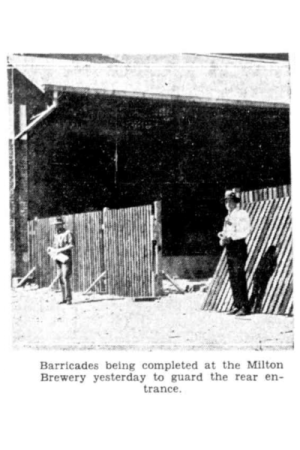

Early in the morning of Friday 24 September, Castlemaine Perkins officials and a large body of police evicted the striking men in what head brewer Mr A.K. Hall described as ‘the quietest thing I have seen in a long time’.

Mr Hall was reported to have reiterated there was no prospect of the company countenancing the men’s demands but that they could apply for re-employment under pre-strike conditions.

It was a surprise eviction for the striking men on the morning of Friday 24 September.

The men quietly packed up their belongings and filed out of the packing room, taking up residence under a nearby house before setting up camp under a hired marquee on nearby land - a camp that was to be known as "Hill 60". For Jimmy Hayes, this was ‘the greatest day of the strike’.

‘We ... had a meeting to decide what we would do, and we then agreed to hire a marquee tent and erect it in Mr. Raines paddock,’ he writes. ‘We approached Mr. Raine who kindly allowed us to put up our tent on his ground, much to the chagrin of our enemy, “The Brewery Heads”. It hurt them very much to see the way we “dug in”. They could see that we meant business.’

The strike continued with picket lines at Milton and Fortitude Valley breweries, with all beer brewed at both still considered "black". Bottled beer was brought in from the Northern Rivers, Sydney and Melbourne, to keep Brisbane locals happy.

On September 28, the Brisbane imprint of the Australian Workers Union (AWU) publication The Worker declared in an editorial that the brewer’s strike was ‘stupid ... ill-timed and unnecessary’. Nonetheless, the strikers remained in camp near the Milton brewery.

Interestingly, the AWU at this time successfully applied to the Industrial Court for a 40-hour week for workers at Cairns Brewery (however this variation to the Northern Breweries Award came with a host of caveats).

'Beer on Monday': the show must go on

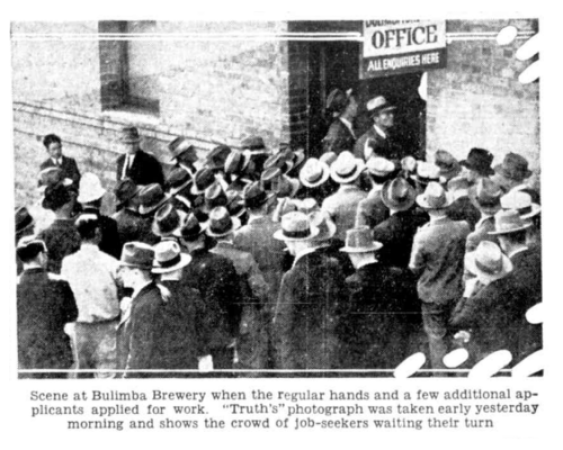

On Thursday 7 October, the Brewers’ Association placed a prominent advertisement in The Telegraph calling for those seeking labour at Castlemaine Brewery and Bulimba Breweries to present themselves at both locations the following Saturday morning.

A reported 200 men (Hayes claims 500) turned up to apply for work at Milton on Saturday 9 October, along with the familiar sight of picketers on the opposite side of the road. Similar scenes occurred at Bulimba Brewery.

Hayes recalls the scene vividly: ‘The scabs stood on one side of the road and we stood on the other. We had papers with “40 hour week on them”, and as the trams came along, we pointed to the scabs for the benefit of the tram passengers.’

Apart from some heckling (‘look at the scabs!’), the event passed without incident. Notably, none of the strikers applied to be reinstated. The stated plan was that there would be ‘beer on Monday’.

Last drinks: the end of the strike

Kegs of Castlemaine Perkins draught beer finally returned to pubs and hotels on 13 October, but not brewed or delivered by union workers. The FLTUQ declared this beer to be "black", and picketing continued outside breweries and hotels.

For Brisbane drinkers, however, the first taste of draught beer in over a month was particularly sweet, even at breakfast.

Anyone for a breakfast brew?

By now, resolution among the striking men was wavering.

After a meeting of strikers from Milton and Valley breweries on Thursday 14 October 1937, the strike was officially called off. The men returned to their camp to have a final dinner, before packing up their belongings and taking down the marquee.

Where to lay the blame for the outcome (and indeed, how best to classify the outcome) was a point of contention among union members. Discussion during the 14 October meeting, and an analysis written by strike participant Michael Patrick Ryan later obtained by police, focused on a lack of planning and communication around the strike, while also apportioning blame to other unions, including the Federated Engine Drivers and Firemen’s Association (FEDFA), whose members had not ceased maintaining refrigeration of beer during the dispute.

During an appearance at the Industrial Court for 'equal pay for equal work among the sexes' for bar attendants, Mr D.J. Skehan, secretary of the FLTUQ admitted, in relation to the stay-in strike: ‘we have made a mistake and will abide by arbitration in the future’.

According to Jimmy Hayes' account, 'Right up to the eviction, everyone was happy and contented and determined to see the fight out to a finish.'

In summing up the tumultuous month as part of a July 1982 feature on beer shortages, the Castlemaine Perkins company magazine Fourex News, notes that 'the sad part was that the 40 hour week was allowed not long after this strike.'

The Court of Conciliation and Arbitration approved the 40 hour week in 1947, which took effect from 1 January 1948. In 1950 the Arbitration Court set the female rate of pay at 75% of the male rate. It was not until 1969 that the Arbitration Court ruled equal pay for women, to be phased in over 4 years, culminating in 1972.

In her detailed history of the 'beer famine' that appears in The Queensland Journal of Labour History, Carol Corless sums up the strike’s end in this way:

'While this dispute left many of the strikers still out of work ... they showed courage in the face of opposition from the employers, the government and from some other unions. These men never wavered from the ideal of the 40-hour week and displayed incredible valour among the vats.'

Resources

- 1937 Castlemaine Brewery Dispute: “Valour Among the Vats”, Carol Corless, in The Queensland Journal of Labour History, number 28, August 2019 [PDF], Brisbane Labour History Association website, accessed 13 September 2024

- Australia's industrial relations timeline, Fair Work Ombudsman website, accessed 13 September 2024

- A beer for Queensland tastes - the history of XXXX and Castlemaine Perkins Brewery, State Library of Queensland website, accessed 13 September 2024

- Bulimba Sparkling XXX Ale, State Library of Queensland website, accessed 13 September 2024

- Brisbane brewery strike: Northerners forced to drink Resch’s and Richmond beer!, Time Gents website, accessed 13 September 2024

- The fight for the 40 hour week, State Library of Queensland website, accessed 13 September 2024

- Fourex news, July 1982, Castlemaine Perkins Limited, John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland

- Jimmy Hayes Manuscript 1937, Jimmy Hayes, John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland

- Men queuing for work at the Milton brewery, Brisbane, 1937, 2003, John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland

- Police storm Brisbane brewery ‘sit-in’ during 1937 strike for 40-hour week, Time Gents website, accessed 13 September 2024

- The Queensland journal of labour history, 2012-2024, Brisbane Labour History Association, John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland

- Trove (various pages), Trove website, accessed 13 September 2024

- Work and strife in paradise : the history of labour relations in Queensland 1859-2009, 2009, Bradley Bowen et al., Federation Press, John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland

Comments

Your email address will not be published.

We welcome relevant, respectful comments.