Kordak: Asian Restaurant Owners oral histories project

By Dr Eun-ji Amy Kim and Dr Aaron Teo - 2024 John Oxley Library Honorary Fellows | 24 April 2025

Dr Eun-ji Amy Kim and Dr Aaron Teo - 2024 John Oxley Library Honorary Fellows

From Migration to Entrepreneurship: The Story of Kordak

In the bustling suburb of West End in Brisbane, a small Korean chicken restaurant called Kor-Dak has been winning hearts with more than just its food. Behind its success is a story of migration, perseverance, and a beautiful Korean concept called "정" (Chong) that owners Miya and Will Park have brought to Queensland.

Kor-Dak is an authentic Korean street food restaurant in Brisbane, Queensland run by siblings Will and Mia Park.

The Journey to Queensland: Riding the Wave of 2000s Migration Policies

Miya Park first arrived in Queensland in 2006 on a working holiday visa. Originally studying early childhood education in Korea, she came to Australia at her uncle's suggestion to study English and explore future opportunities. Family connection was a key pull factor in coming to Queensland - her uncle lived in Inala, providing her with a home base as she settled in.

The mid-2000s marked a significant shift in Australia's migration policies, with the country actively expanding pathways for Asian migrants. In 2005, Australia had introduced reforms to its Working Holiday Maker programme, opening doors to young people from Asian countries including South Korea. [1] This reform created a surge in Korean working holidaymakers coming to Australia, which Miya describes as "fashionable in Korea" at the time.

Her brother Will followed in 2008 as a high school student, similarly drawn to Brisbane because his sister and cousin had already established themselves there. "I came to Brisbane as my cousin and my sister were living here. So yeah, just went to high school study and yeah, loved it," Will explains. For both siblings, these family connections made Queensland the natural choice for their Australian journey.

Their early days in Australia brought immediate challenges that shaped their migration journey. Miya's first experience at an English language school revealed an unexpected reality: "In the class we had like about 28 students but then more than 80% were Koreans." Finding little value in paying for classes where she predominantly spoke Korean with other Korean students, she began studying English independently, working during the day and studying newspaper articles with her brother at night. Securing permanent residency quickly became her primary goal, influencing many of her subsequent decisions.

After studying childcare initially, Miya found herself in a difficult situation when her program was cancelled:

“They cancelled the diploma class because they're short of people, they're short of students... but then as a visa holder I needed to find something in about two months, otherwise I have to go back."

She wasn't ready to return to Korea: "But then I couldn't go back because my English wasn't perfect, I didn't prepare, and I don't know what to do when I go back."

Her uncle strongly encouraged her to pursue PR, telling her, "You should get the permanent residency because at the time if you get, like a five score for the IELTS then you can easily permanent residency." The migration policies at the time made it relatively straightforward to obtain PR through certain education pathways. As Miya explains, "So whoever studied cookery or like hairdresser, they can just get permanent residency."

This pushed her toward studying commercial cookery as a path to PR.

Will explains that at the time, Australia's immigration policies were quite open: "At that time the immigration law was quite of open to everyone. It was from like tradies up to any skilled workers as they were short of skilled workers." He studied specific trades to qualify for PR: "So I was studying as a cabinet maker to get the residency."

Overall, both siblings were strategically responding to Australia's skills-based migration policies of the mid-2000s, which created pathways to permanent residency through studying and working in fields that were on the skilled occupation list. This was particularly important as they had begun to establish their lives in Australia and saw better opportunities for themselves in Queensland than back in Korea.

During this period, Australia's migration system favoured skilled migrants, particularly in occupations on the government's skills shortage list. As Miya explains, "At the time if you get, like a five score for the IELTS then you can easily get permanent residency. So whoever studied cookery or like hairdresser, they can just get permanent residency." This policy environment shaped her educational choices, eventually leading her to study commercial cookery despite her background in early childhood education.

Will's experience as a high school student had its own challenges. He found himself surrounded by wealthy Korean students who weren't motivated to study, which ultimately led him to drop out and pursue a different path through TAFE, where he found a more mature environment that helped him grow.

Facing Discrimination in the Workplace

Both siblings encountered various forms of discrimination throughout their professional journeys in Australia. Miya's experience as an Asian female chef in a predominantly white male industry was particularly challenging.

"I was shocked because all the chefs were pretty tall and big and they're like men, men, men. They look at me like, what's a little Asian girl coming with the big toolbox," she recalls.

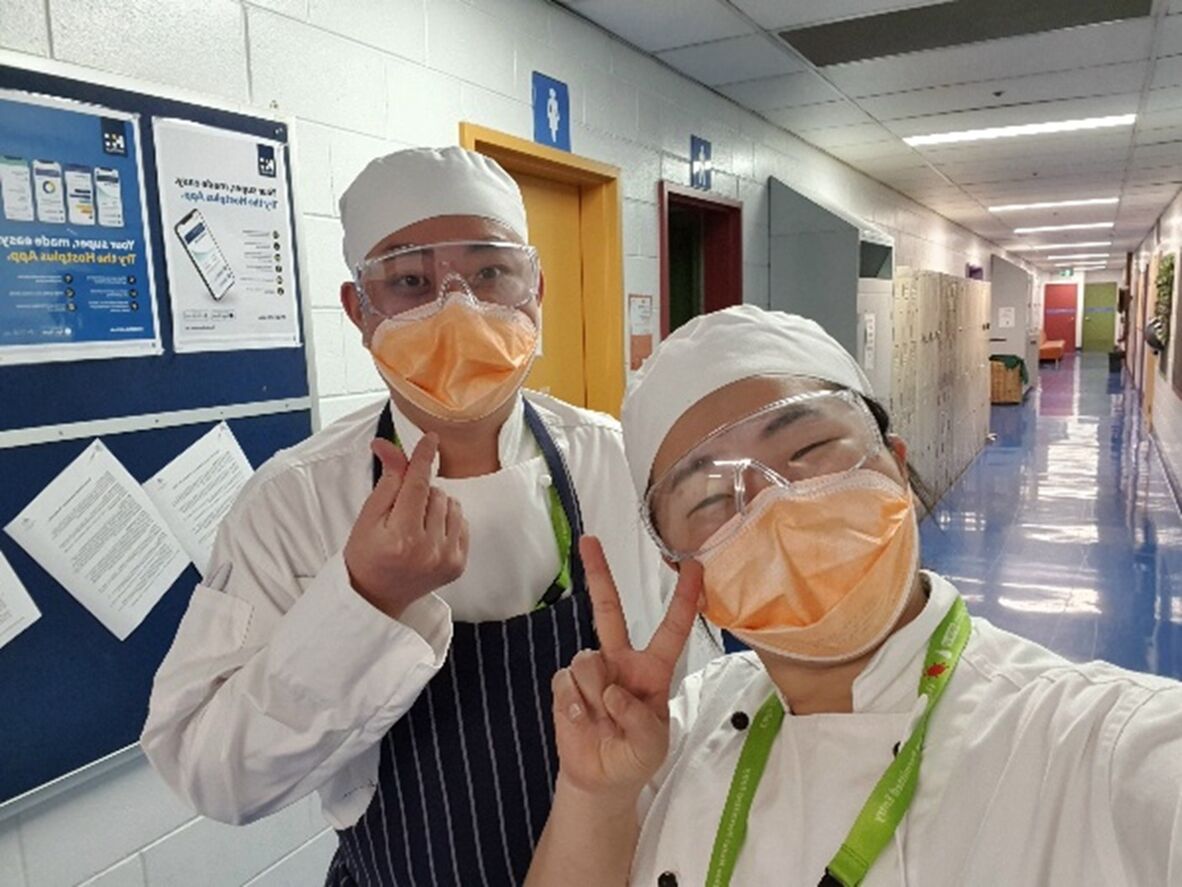

Miya Park, studying cookery at TAFE.

When offered a promotion to a supervisory position, she faced resistance from colleagues who claimed they wouldn't work for her because she couldn't even "lift the 100 litres of port." Miya wondered if this was racism or sexism, especially when she noticed that European female chefs didn't face the same scrutiny.

Will experienced what he calls "indirect racism" in the hospitality industry. Despite being hired as a food and beverage attendant, he was consistently scheduled for

housekeeping shifts instead of customer-facing roles. When he raised concerns, his shifts were reduced drastically to the point that working there was no longer tenable.

Their experiences mirror findings from research on Asian Australian workplace experiences. A 2020 Australian Human Rights Commission report found that 66% of Asian Australians reported experiencing workplace discrimination, with particularly high rates in customer service and hospitality industries.[5] This discrimination often manifests as "occupational segregation" where Asian workers are channelled into back-of-house roles regardless of their qualifications and language abilities.[6] Miya and Will described this as the "unknown rules" in the hospitality industry, where non-native English speakers were typically assigned to back-of-house roles with minimal customer interaction, regardless of their qualifications or desire to work in front-of-house positions. As Miya puts it: "If you are like non-English speaker or like your English is your second language... They put you in the morning, not at night time... It's just because the hotel in the morning means you're working in the buffet. So which means you don't have interactions with the people."

This aligns with research showing that Asian migrants often experience "accent discrimination" that affects their career progression, with employers assuming customer preferences for staff with "Australian" accents, particularly in front-facing hospitality roles.[7]

Despite these challenges, both siblings have chosen to make Queensland their permanent home. When asked why they stayed in Queensland rather than moving to larger cities like Sydney or Melbourne, Miya enthusiastically praises Brisbane's unique character:

"I pretty much love the vibe. Like it's enough busy but enough chilling. And then because we had all experiences in here, like living a long time, and I find that the Queensland people are more pure, and they're very welcoming as well. And they have really good heart."

Will agrees, noting the cultural difference in everyday interactions: "In Asia, in Korea, especially if you just walk on the street, and if you make eye contact with a stranger, that means they're being aggressive... But here, if you're just walking, and then make eye contact, you'd just say, 'Hi!'" This friendliness made a lasting impression on him.

Building Kordak: A Post-Pandemic Entrepreneurial Journey

Their journey to entrepreneurship began almost accidentally. After Miya suffered an injury that prevented her from continuing in commercial kitchens, Will discovered someone selling chicken skewer equipment at the Redcliffe Market. They decided to try

selling Korean chicken skewers, noticing that while there were Vietnamese, Japanese, and Filipino options, Korean skewers were missing from the market.

They launched at New Farm Farmer's Market in March 2023, working through 38-degree heat with charcoal grills.

Kor-Dak Korean Street Food Market Stall at the New Farm Famer's Markets.

Jumbo Skewers from Kor-Dak Korean Street Food Market Stall at the New Farm Famer's Markets.

This timing placed their business launch squarely in the post-COVID recovery period, when Australia was experiencing a significant restaurant boom. According to Restaurant & Catering Australia, the industry saw a 16.2% increase in new restaurant openings in

2022-2023 compared to pre-pandemic levels, as Australians embraced dining out again after lengthy lockdowns.[2]

Initially, they struggled to attract customers who were unfamiliar with Korean chicken. But through persistence, bright yellow signage, and free samples, they began building a loyal customer base.

The transition to a brick-and-mortar restaurant was coincidental, when Will, while driving his bus route for Brisbane City Council, spotted a "For Lease" sign on Montague Road. "If it caught my eyes, it would be a good spot," Will reasoned. They opened Kordak in January 2024, doing all the painting and design work themselves.

Navigating Changing Migration Policies

The ongoing changes to Australia's migration policies continue to affect Kordak's business. Miya notes that recent policy shifts have impacted their customer base: "A couple of months ago the migration law has had changes. They announced that they've minimised the invitation to the people and then there's few jobs being taken off from the list. So then our few regular customers had to go back their country."

This refers to Australia's mid-2023 migration reforms, which tightened student visa requirements and reduced the occupations eligible for skilled migration pathways.[4] Will explains how these changes directly affect their business strategy: "Since the student visa is getting harder, and also the rent is getting expensive... It's expensive and people are, the young students are moving out from this suburb or going back to their country. So our target market has changed."

Despite these challenges, Kordak has adapted by broadening its appeal beyond the initially targeted demographic of "half of young professional married couples, with one very young kid, or students that go to UQ."

Building Cultural Bridges

Recognising the difficulty in connecting Australian and Korean communities due to language and cultural barriers, Miya and Will have positioned Kordak as a bridge between cultures.

They host weekly "meetups" on Wednesdays at 6:30 PM for anyone interested in learning about Korean culture or sharing their own cultural experiences. Last week’s gatherings included a barbecue where New Zealanders brought New Zealand desserts, and an Australian brought homemade Korean rice cakes.

Despite serving traditional Korean street food prepared with authentic methods (Miya makes fish cake soup broth from scratch rather than using powder), Kordak attracts more international customers than Korean ones. This surprised even the siblings - a lawyer once pointed out that they weren't writing any Korean in their Instagram posts, something they hadn't even realised.

When asked what wisdom they would share with future generations of Queenslanders or Koreans coming to Australia, Will points to a curtain in their restaurant that reads, "Kind is the New Cool."

"Be kind and treat people how you want to be treated," he advises.

Miya returns to the concept of "Chong," emphasising the importance of not losing one's humanity in the face of discrimination. "Even though you feel the racism or discrimination, it's going to end," she says. "If you just keep reaching to them with the 'Chong,' then they will understand."

She describes how they responded to initial resistance with persistent kindness - offering samples, chocolates with delivery orders, and genuine warmth. "It's just a matter of time. Don't get hurt... don't do the revenge. You just reach with more 'Chong,' more heart, more caring. Then they're gonna melt their heart."

In a world where divisions and discrimination remain prevalent, Kordak serves not just Korean chicken, but also a philosophy that bridges differences through simple human kindness. And in doing so, the Park siblings have created something more valuable than a successful business - they've built a true community.

View the full collection of digital stories from the Asian Restaurant Owners Oral History Interviews project. Enjoy a preview of the Kingsfood digital story below, along with Dr Kim and Dr Teo's Research Reveals talk, talk discussing their project and findings.

Promo video for the full Kor-Dak digital story, part of the collection, Asian Restaurant Owners oral history interviews.

Kor-Dak, an authentic Korean street food restaurant run by brother and sister Will and Mia Park.

Dr Aaron Teo & Dr Eun-ji Amy Kim's Research Reveals talk.

Read more blogs about this project by Dr Eun-ji Amy Kim and Dr Aaron Teo.

Read more blogs by State Library's Queensland Memory Fellows.

References

[1] Department of Immigration and Multicultural Affairs. (2005). Annual Report 2004-2005. Commonwealth of Australia.

[2]: Restaurant & Catering Australia. (2023). Hospitality Industry Outlook Report 2023. Retrieved from: https://squareup.com/au/en/the-bottom-line/selling-anywhere/futureofrestaurants23

[3]: Property Council of Australia. (2024). Queensland Retail Market Report - Q1 2024.

[4]: Department of Home Affairs. (2023). Migration Program Planning Levels. Commonwealth of Australia.

[5]: Australian Human Rights Commission. (2020). Racism in Australia: A snapshot of the experiences of Asian Australians. Sydney: AHRC.

[6]: Soutphommasane, T., Whitwell, G., & Jordan, K. (2018). Leading for Change: A blueprint for cultural diversity and inclusive leadership revisited. Australian Human Rights Commission.

[7]: Booth, A., Leigh, A., & Varganova, E. (2012). Does ethnic discrimination vary across minority groups? Evidence from a field experiment. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics, 74(4), 547-573.

[8]: Collins, J., & Shin, J. (2021). Ethnic entrepreneurship and community resilience: Korean-Australian entrepreneurship in Sydney. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 47(13), 2957-2976.

Comments

Your email address will not be published.

We welcome relevant, respectful comments.