Guest blog by John Dingle

When His Royal Highness Edward, Prince of Wales, visited Australia in 1920, most Australians were aware he had been in uniform and had served for four years in France and possibly even that he had served in Belgium and Italy in The Great War. In addition, he was considered handsome and was the epitome of the well-dressed fashionable 1920s modern man who enjoyed dancing and fast cars. He was therefore warmly welcomed wherever he went.

![Souvenir of Visit of His Royal Highness, The Prince of Wales [Edward VIII] to Australia 1920. "Our Digger Prince"](/sites/default/files/styles/slq_standard/public/Souvenir%20of%20Visit%20of%20His%20Royal%20Highness%2C%201920_1.jpg?itok=b8yM2Aez)

Souvenir of Visit of His Royal Highness, The Prince of Wales [Edward VIII] to Australia 1920. "Our Digger Prince". Design & photo by Gunner Les Wilson MM, Melbourne. Source: Libraries Tasmania LPIC147-6-139, Series: Launceston Collection of Photographs of Places, Events, Buildings and General Subjects

Edward Albert Christian George Andrew Patrick David, His Royal Highness, The Prince of Wales, was only 20, the minimum age for enlistment, when the First World War broke out in 1914. He had been in training and immediately asked his father, King George V, if he could join the Grenadier Guards. This was arranged, even though Edward was only 5’9” and the minimum height for a Grenadier Guard was 6’. He was eager to go to the front but the Secretary of State for War, Lord Kitchener, forbade him, not because he might be killed but because he might be captured and used as a hostage.

Edward lobbied hard and in November 1914 was appointed to a junior staff officer role in France at the Head Quarters of the Commander of the British Empire Forces (BEF), Sir John French. Edward used every opportunity to visit the front and was eventually assigned to logistics near the front. He visited advanced positions and was under fire in front area dug outs many times.

During the Battle of Passchendale he recalls “got the most vivid close-up of the horrible existence that had become the lot of the British soldier”. In 1915 during an inspection of the second line his driver was killed. He recalls “columns of bloodstained shreds of khaki and tartan: the ground grey with corpses: mired horses struggle as they drowned in shell-holes”. In uniform, Edward assessed munition dumps and investigated the aftermath of air raids with relative anonymity, riding a dispatch bicycle.

He later wrote in his autobiography A King’s Story - “I often think I learned about war chiefly on a bicycle. My duties constantly took me back and forth between the various units; and although entitled to a staff car, I seldom used one within our area. The automobiles of the brass hats honked infantrymen off the road into ditches, splashed them with mud, and, even under the best circumstances, were an irritating reminder of the relative comforts of life on the staff. My green Army bicycle was a heavy, cumbersome machine. But on it I must have pedalled hundreds, even thousands of miles, collecting material for reports, inspecting camps and ammunition dumps. My brother officers laughed at me for preferring this hard way of getting around, but they missed the point. Just as had my first bicycle at Sandringham, my Army bicycle opened up for me a whole new world of unexpected associations. Even now, after three decades, I still meet men who will suddenly turn to me and say, ‘The last time I saw you, you were on your bicycle on the road to Poperinghe’ – or any one of a hundred French villages.”

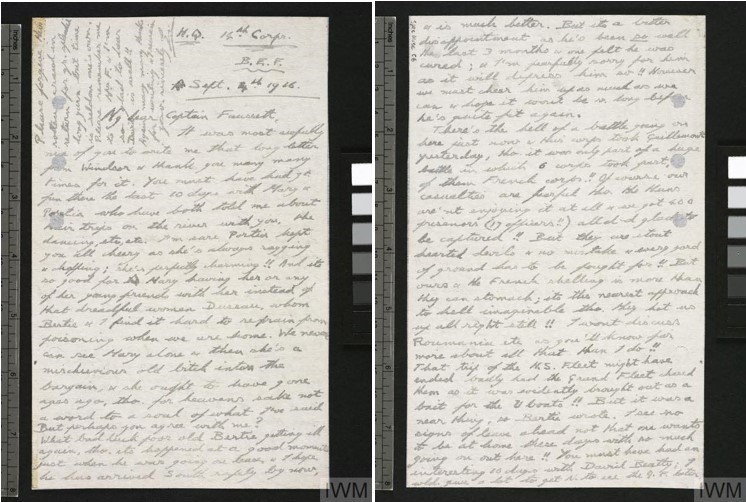

Correspondence in HM King Edward VIII, Private Papers. Source: Collection Imperial War Museum, United Kingdom, 14th Corps, B.E.F., letter dated Sept 4, 1916.

With his unit of Grenadier Guards, he took part in the Battle of Guillemont on the Somme 3 – 6 September 1916. During the battle Edward wrote to Captain Faussett, aide-de-camp to his father, King George.

My dear Captain Faussett,

It was most awfully nice of you to write me that long letter from Windsor & thank you many many times for it. You must have had gt fun there the last 10 days, with Mary and Portia who have both told me about their trips on the river with you, the dancing, etc, etc…

…There’s a hell of a battle going on here just now as this corps took Guillemont yesterday, tho it was only part of a huge battle in which 6 corps took part w the French corps!! Of course, our casualties are fearful tho the Huns aren’t enjoying it at all & we got 400 prisoners (1 officer!!) All glad to be captured!! But they are stout hearted devils & no mistake, but every yard of ground has to be fought for!! But ours & the French shelling is more than they can stomach; it’s the nearest approach to hell imaginable. They hot us up all night still!! I won’t discuss Roumania [declaration of war] etc.as you’ll know far more about all that than I do!!

…Please forgive this rotten scrawl in return for yr splendid long yarn, but time is seldom one’s own. Please remember me to Mrs F. & I’m so glad to hear David is well!!

Again many many thanks for writing & I remain

Yours sincerely

E.

Read the entire letter digitised by the Imperial War Museum, United Kingdom.

Edward was awarded the Military Cross for his actions in 1916.

![Entry in publication Roads were not built for cars, by Carlton Reid 2014 showing Hitler’s name, place, date of birth and role ‘Radf.’ [Radfahrer: cyclist].](/sites/default/files/styles/slq_standard/public/Entry%20showing%20Hitler%E2%80%99s%20name%20date%20of%20birth%20and%20occupation%20resized_0.jpg?itok=23R_0Edy)

Entry in publication Roads were not built for cars, by Carlton Reid 2014 showing Hitler’s name, place, date of birth and role ‘Radf.’ [Radfahrer: cyclist].

By coincidence, Edward’s experience was paralleled on the other side by a 27-year-old Adolf Hitler, who was also a bicycle dispatch rider, as shown in part of his military record.

Hitler’s job was to transfer communications to and from the front lines to the command post, often through artillery bombardments, gunfire and gas. One month later on the 7 October 1916 in the Battle of Bapaume nearby, Hitler was hit by shrapnel in the left thigh, left behind in the retreat but was evacuated by stretcher the next day. He spent the next five months in hospital. He was awarded the Iron Cross twice for his actions during World War I.

Cyclists sheltering from shelling, Western Front, during World War I, circa 1918, Source: Acc.3155, National Library of Scotland.

Comments

Your email address will not be published.

We welcome relevant, respectful comments.