The Hempress of the Barcoo – What an Englishwoman saw in Qld in 1892

By JOL Admin | 15 August 2011

“The India rubber bath stands us in great stead, we always get a cold bath every morning.” pp 132-133

Alice Heber Percy, of Hodnet Hall, Shropshire, travelled with a rubber bathtub and a notebook, carried a shotgun and a polished interest in her surrounds, and was hastily vaccinated against smallpox in Sydney in 1892. She managed a visit to the Botanical Gardens and to the “Actualization Gardens” before heading out of town to escape possible quarantine, knowing that smallpox had been found onboard the ship. She was a woman from England who travelled First Class on the Ophir and then the Oraya, passing Spain and Gibralter and disembarking at Port Said where, as an educated seeker-of-experience she visited a Bedouin Camp and described it in detail. In fact, her diary is full of excursions and asides of the edifying and entertaining variety. Her writing is elegant and there are often maps and illustrations too, which made me imagine contemplative evenings with coloured pencils and ink, before realising that the diary was likely constructed after the fact, from a more weather-stained and crossed-out original that no longer exists.

Instead, this is another diary in the John Oxley Library, which begins as a shipboard tale and ends as both international and Australian, as colonial life becomes both an experience and a site for stories and performance. Shearers, the sugar industry, station life, the quality of hotels, inferior circuses and outback “characters” all appear, but again and again the Aboriginal domestic workers and adjacent Aboriginal “camps” are described and visited as tourist sites.

Most of the Australian excursions in the diary happen in Queensland. There’s an opaque family history behind it, in which an uncle was apparently killed by Aborigines. The story seeps through, but isn’t entirely spelled out.

And while there is a tone of privilege and what we might now call “entitlement” to her diary, it also is defined so very clearly by intelligence and curiosity. By energy, however hearty.

It also pulls you up, with reminders of what nineteenth-century British womanhood could encompass. Heading out to look at the animals and breathe in the bush, seeing a Large Native Bear in a Gum Tree and then “bagging” it. She was handy with a gun. Wondering how to take home a kangaroo she’d shot, and had the “blackboy” skin, as a memorial of this Queensland adventure.

As always, there’s the economy too. Some of the properties she visits with her family belong to family friends; others seem to be paid sites, stops along the way, in a sort of fin de siecle “farm stay”, with a corroberee or boomerang throwing for entertainment in the evening, although at the property near Marlborough, she said the latter “performance was poor”. It was Sunday, 31 July:

“In the evening we walked down to the Blacks camp, and talked to them, and admired the little piccaninny who is fat as butter, and with a skin like velvet, he wears no clothes; the gin his mother down nothing but nurse, and play with him all day long; there are very few children among the blacks, all the tribes are dying out, expedited greatly by their excessive love of smoking Opium, they implore the Chinaman to empty his pipe when he has finished smoking, that they may have the refuse: a law has been past making it illegal to sell them Opium; also if they catch cold it always settles on their lungs and now that they have taken to wear clothes instead of possum rugs, they get wet and never change out of wet clothes . . .”

At another stop on the journey, she describes dances that were performed by local Aboriginal people in great detail, and then adds that, “Mr Shaw gave the Blacks a lot of Lollipops and Tea and they were quite happy.” P 150

Some people may find these 1890s descriptions distressing. She seems to reveal a complicated set of relationships and attitudes, and while almost every station she visits has an associated camp, many also have servants who are described, in particular, by their clothes, their uniforms, their symbols of work. At Elderslie Station, for example, Mrs Slaggart:

“dressed the Black Gins who do the household work in white dimity edged with red, and their aprons with bibs, the same; I watched them camp in a circle on the ground just outside the verandah and eat up the remains of breakfast, and dinner without any plates, they smoked short clay pipes afterwards.” P 133

While the whole diary is framed by the great shipboard journey on the Ophir and the Oraya, domestically, they travel in many different ways. Cobb & Co, horse, and by train from Rockhampton to Longreach, which was crowded because of a racemeeting on the 27 August. And then, as they travelled out to visit various stations, it was the state of the landscape that struck her, after a long drought, where “all the uneaten grass is straw coloured” and the ground around the waterholes has been eaten down to the state of a thoroughfare from the other side of the world: “bare like a turnpike road.” There’d been no rain for 19 months. Even so, there was time for the working life of a station to be part of the show, and so they watched the shearing, whose industrial conditions and political tendencies were carefully controlled and explained for an educated visitor who carefully recorded the processes for us. The version of work comes from the station owner, Mr Chermside:

“The Shearers are well paid men, they move from Station to Station as there is work, usually the same hands are employed year after year, they own as a rule two good horses, one to ride, and the other a pack horse, and carry with them a comfortable tent; the station feed them with good rations, the shearers provide the Cook.” P 131

And so while in hindsight we see the 1890s shearers strikes and their role in both nationalism and union tradition, that particular part of a self-conscious identity passed this woman traveller by. Other familiar stories, and archetypes, do crop up though. Along with the “servant problem”, stories of irreverence and the larrikin, the puncturer of ego, and perhaps the putting down of certain types of women, are also there to be found in this diary. And stories need not be experiences, to be included. This one was told to her, about a woman who lived somewhere on the Barcoo River, and who held herself in very high esteem. She was, it was said, “very exacting with her servants” and insisted that her cook come and wait at table – and she told John, the cook, to take the covers off:

“he took the cover off the junk of salt beef, and clapped the cover on Mrs Cameron’s head saying ‘I crowned you the Hempress of the Barcoo’ and swaggered off with his hands in his pockets.” P 162

Domestic and other workers are everywhere in the diary. Not just the Aboriginal domestic workers and the travelling shearers, the cooks with a sense of humour and the hotel workers of questionable skill, but at the Homebush Sugar Plantation there were Pacific Islanders – “kanakas” she calls them – who worked the cane; and they were waited on by a "Cingalese" servant (who, it’s been argued, might represent a colonial, Singaporean version of living in the North, where “manservants” of various ethnicity took a particular version of Asian colonialism as its model – or at least, this is an argument that’s been made for Darwin. Does it hold true for Qld, I wonder? This has been argued in the unpublished work of historian Claire Lowry). Again, this is an opportunity for her to present a detailed disquisition on methods of sugar cane farming.

And so with her learned exposition and enthusiastic, descriptive engagement with Australia and with Qld, sometimes it’s hard to know what to make of a curious incident, apart from its curiosity. The importance of the handkerchief and hat, even, reminds us that social codes really are specific and historical. And then there’s cross-dressing eccentricity. Impossible to make a hurried conclusion about this, but I’ll make a stab at a bit of playful role reversal:

“Mr and Mrs Beardmore are quite crazy. Mr Beardmore they tell us dresses up in his wife’s clothes and cooks the dinner, he is very fond of this amusement. She goes out with a handkerchief tied under her chin she told us that she will not wear a hat, and that he will not buy poor old Mags a bonnet; they are a strange couple, and are both as mad as hatters.” (Sun Oct 9th), p 166

And then, in November, while neither the diary nor the trip is over, Alice travels by steamer to Townsville and begins her journey home. She didn’t follow through all the byways and places she might have, however:

“We stopped at Cairns but we did not land, they told us there was nothing to see there.” P 187

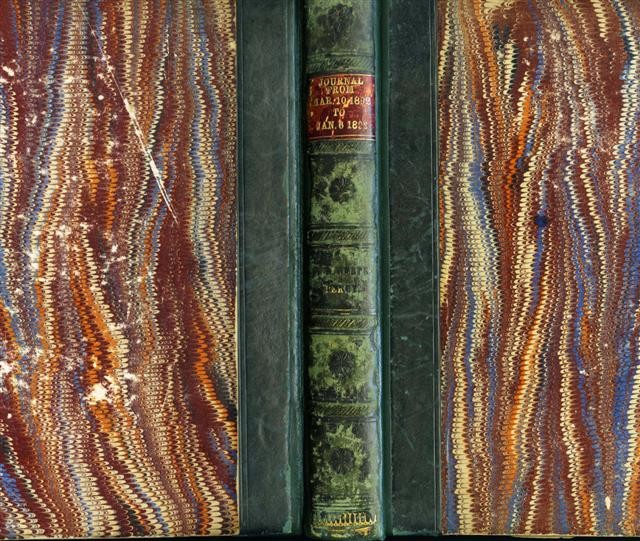

Item referred to: Alice Heber-Percy Handwritten diary, SLQ, JOL OM86-20 (Box 9193),10 March 1892 – 6 Jan 1893

Kate Evans, Historian in Residence, John Oxley Library

Comments

Your email address will not be published.

We welcome relevant, respectful comments.