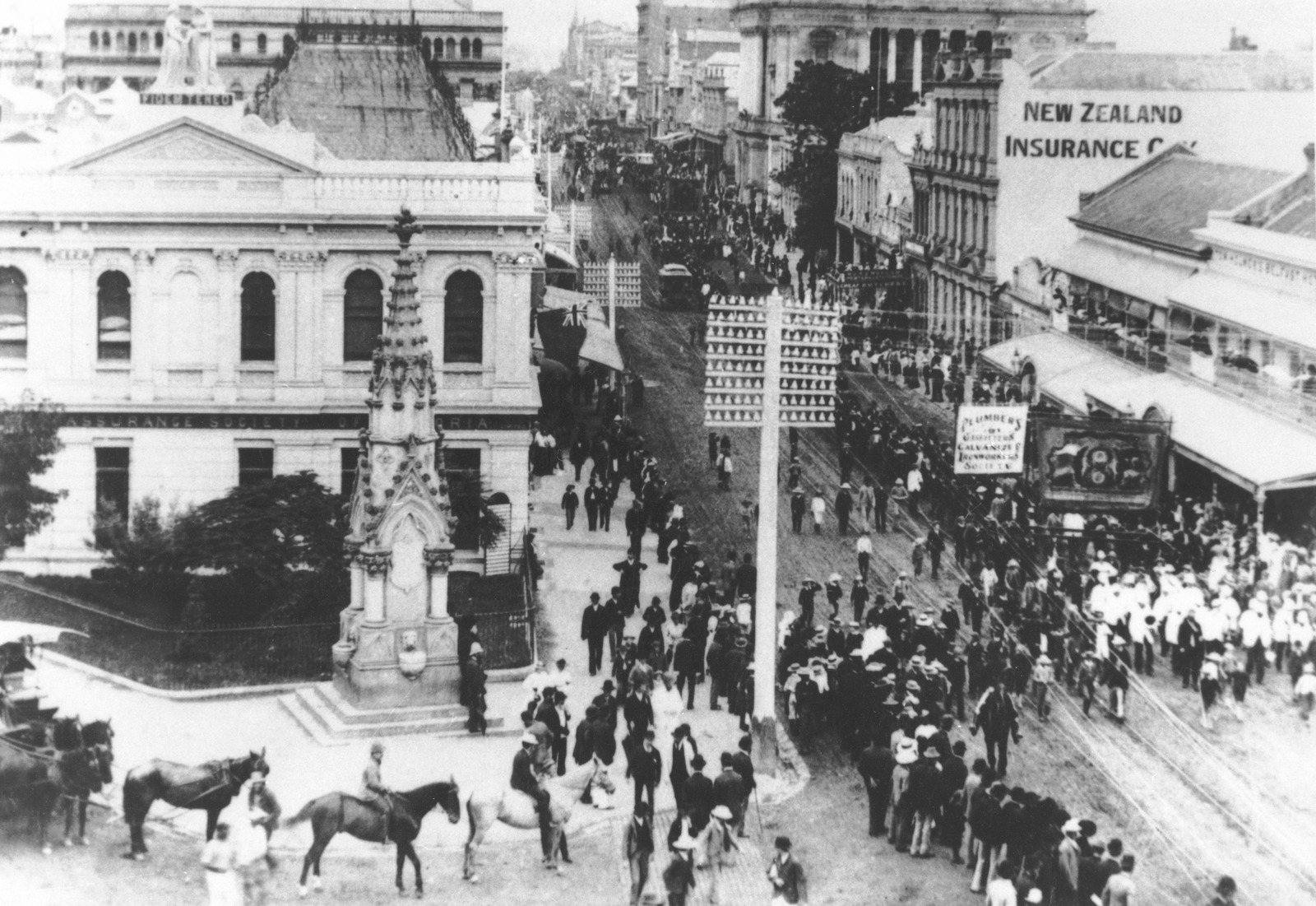

Frank McDonnell And The Early Closing Movement

By Dr Robin Trotter - 2024 Queensland Business Leaders Hall of Fame Fellow. | 6 May 2024

Guest blogger: Dr Robin Trotter - 2024 Queensland Business Leaders Hall of Fame Fellow.

Many Queenslanders will remember the department store, McDonnell & East, in its last reiteration, 414 George Street, Brisbane.

McDonnell & East department store, Brisbane, ca. 1950, John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland, Negative number: 111988.

The founders of this iconic department store were Francis (Frank) McDonnell (1863–1928) and Hubert East (1862-1928). Both were Irish- born. Both emigrated from Ireland in 1886, arriving in Brisbane that year. Both worked as drapery assistants in various department stores: Finney, Isles & Co, T J Geoghegan, Edwards & Lamb, Edwards & Chapman and Allan & Stark. Through working together, they formed a friendship that led to them establishing a formal partnership in 1901 to open their own drapery store: McDonnell & East (Lougheed 1981; MacGinley 1986; Lougheed 1981; Lavis 1986).

But the story of McDonnell & East’s department store is another story. And the story of Frank McDonnell as a business leader and politician is also another story. This story focuses on Frank McDonnell as a social activist and reformer, advocating the rights of workers – and especially the rights of shop assistants. It is a story about the Brisbane Early Closing movement (ECM) and the organisation formed by history and by McDonnell. It is a story that connects with labour history, with the eight-hour day movement, and, obliquely, with the Temperance movement’s fight to reform drinking habits by enforcing early closure of hotels and controlling the serving of alcoholic beverages. (1)

Britain

We can turn to Britain for an early approach to managing working hours, as Simon Rottenberg (1961) summarised:

Great Britain's experience with the regulation of hours by legislation dates at least from the Factory Act 1833. The Factory Act 1833 and its successors did not extend to the shops. The first Act covering shops was the Shop Hours Regulations Act 1866 which defined limits for the weekly hours of work (with any given employer) of young persons. (p.120)

He goes on to locate the precursor to this legislation to a meeting of thirteen men in London in 1842 that agreed:

..the present hours of business are longer than either the convenience or the necessities of the public require, and that a judicious curtailment thereof . . . would be productive of the most beneficial results, both in the moral and physical health of the young men therein employed.

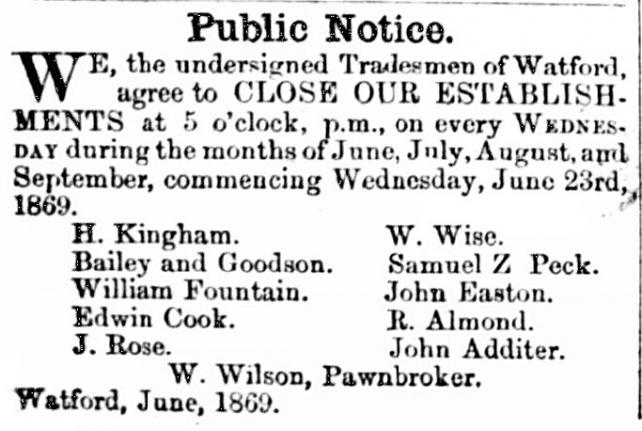

As part of the movement, Early Shopping Leagues were formed to encourage women to shop early in the day rather than in the evenings on the basis of women’s health and well-being. Pressure was exerted first for voluntary early closure of shops, but this quickly moved on to lobbying for legislation to enforce early closing (ibid). This public notice is an example of the voluntary and selective adoption of early closing in one local English community.

The early closing notice published in the Watford Observer in June 1869

For Britain, legislation on early closing didn’t happen until 1906, and even then, the legislation had limitations and exclusions. The history of shop operating hours, across numerous Acts and Amendments, has continued ever since to be controversial and the subject of numerous legislative interventions – both in the UK, and elsewhere. For this story, however, I now turn to Australia and, to the Queensland experience.

Australia

In the Australian colonies, the Eight Hour Day movement and the Early Closing movement were on similar routes, had similar objectives, and sometimes involved the same players. Both took up ideas promoted through earlier Chartist movements and social reformers: both looked to improve working conditions; and both aimed to reform the political, industrial, and social lives of the working classes.

First ‘cab off the rank’ to win their case for an eight hour day were the Stonemasons: Sydney stonemasons winning an 8 hour day in 1855, Melbourne stonemasons in 1856, and Brisbane stonemasons in 1857 (Cross, 2008; Bowden 2011, p.54).

As already noted, the Early Closing associations were formed as early as the 1840s in the United Kingdom, and Australian shop assistants quickly took up local struggles to improve working conditions: initially, in Melbourne in the 1850, and similarly, NSW shop assistants took up the call for early closing by 1874, and in Brisbane, Frank McDonnell organised the Shop Assistants’ Early Closing Association in 1889 – just three years after his arrival in Australia. There is evidence that the shop assistants, in agitating for early closing of shops, looked to those trades that had already won the Eight Hour Day, as this ‘Appeal to the Eight Hour Men’ attests:

Letter to the editor: An Appeal to the Eight Hours Men published in The Argus, 1875, April 21, p. 5

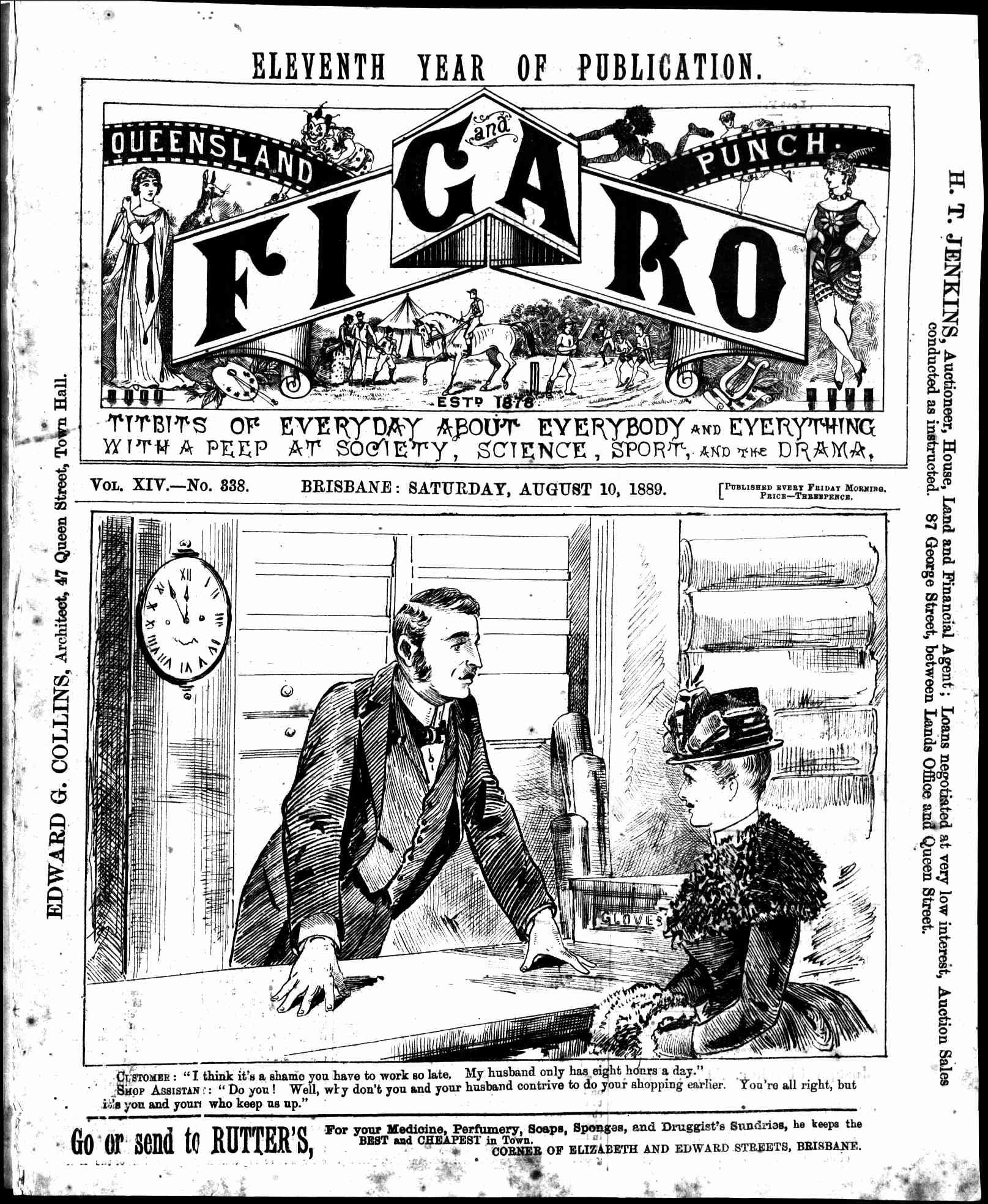

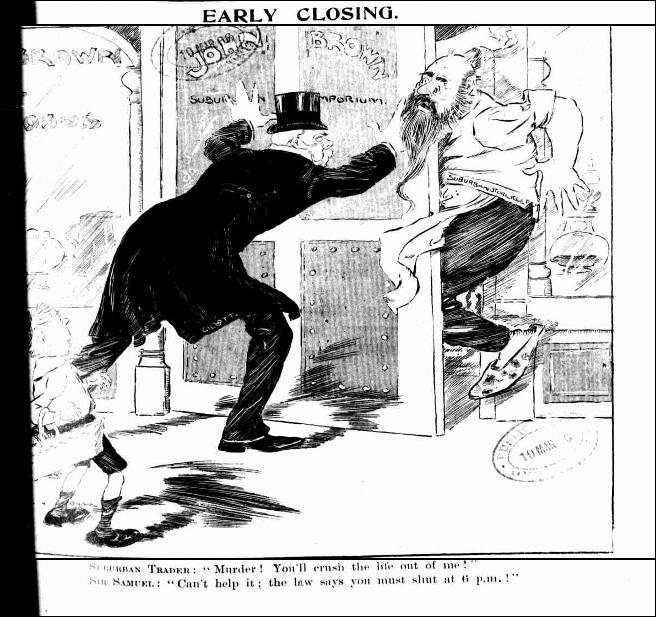

If the ‘8 hour men’ were reluctant supporters for their shop assistant ‘brothers and sisters’, the employers (shop keepers and factory owners) were, in the main, even less impressed with their workers’ requests, even demands, for better wages, shorter hours, and safer working conditions – even after the battle had been won.[2]

[2] There were, however, a number of shops supporting the ECM. For example, Finney, Isles & Co. was one of the first shops to introduce early closing and was a regular advertiser in the movement’s journal, The Early Closing Advocate

Early Closing cartoon illustration appears in Table Talk 1906, March 8, p. 3.

Queensland - A Late Starter in the Early Closing Movement

Georgia Whitfield (1968) summed up working conditions in Brisbane in the 1880s and 1890s: reduced wages, especially for women and children: the prevalence of ‘sweating’ or outworking; extremely long working hours – up to sixty, even ninety hours a week in some occupations; unpaid overtime; employment of children as young as 10; unsatisfactory, unsafe and unhygienic working environments. As William Lane reported in the Boomerang (8 January 1888):

"The position of the working women in the cities of this colony, and more particularly in the capital, is becoming worse and worse every year as the struggle for existence deepens around us and as grinding avarice is thus enabled to take more and more advantage of those who must live. They are becoming herded into stifling workshops and ill-ventilated attics; they are dragged back to work late into the summer nights; and they are forced to stand from morning to night behind the counters of the large emporiums that are the boast of great towns. They are 'sweated' by clothing factories and boot factories. Little ones who should be at school or at play are working in factories and shops, and the law, instead of rescuing them, stands by to ply the whip on their backs if they revolt" (Lane, cited in Whitfield, op.cit., p.23.)

Photograph of William Lane in New Zealand, John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland. Negative number: 191731

Frank McDonnell: an advocate for early closing

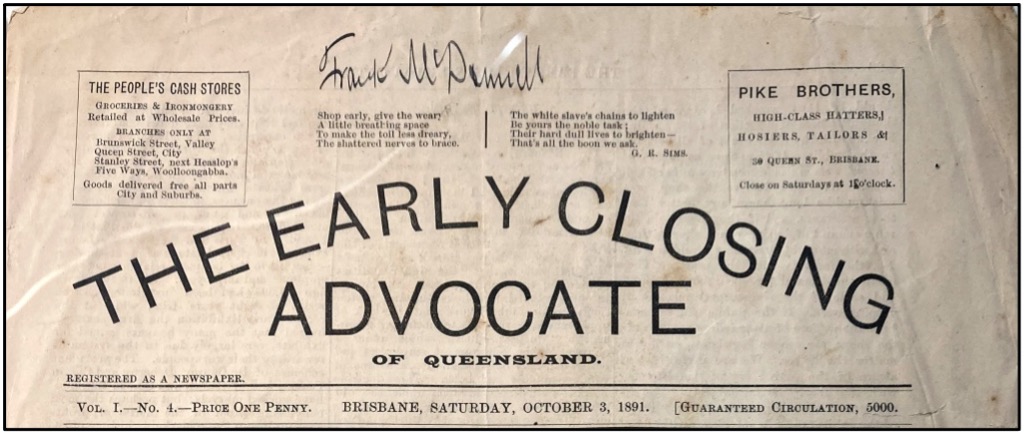

In Brisbane, Frank McDonnell, acting as Secretary of the Shop Employees Union, initiated the Shop Assistants’ Closing Association in 1889. And for the latter, also acting as that organisation’s Secretary, he organised and published the Association’s newsletter, The Early Closing Advocate of Queensland (MacGinley 1986).

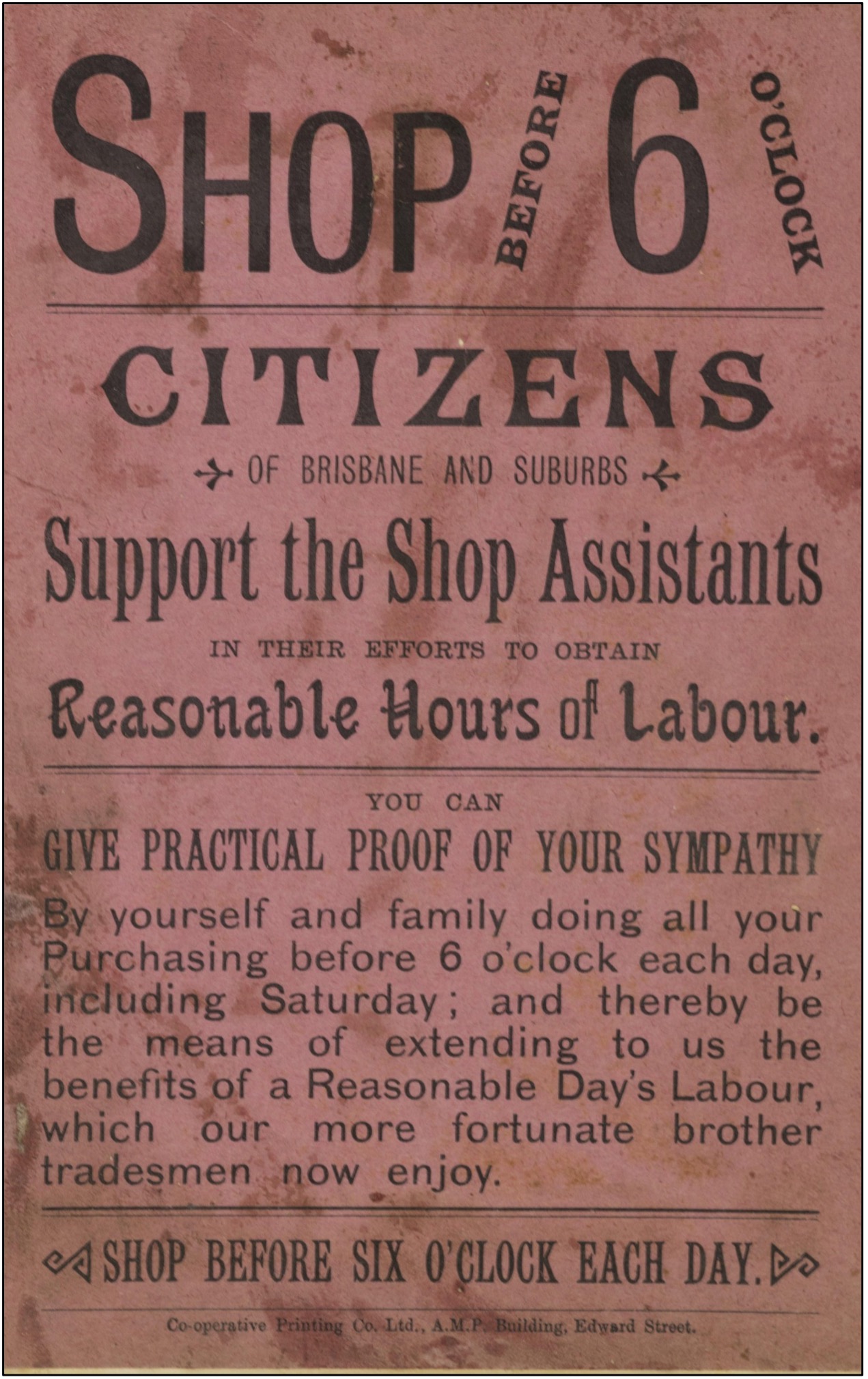

The Early Closing movement initially took a ‘softly, softly’ approach by wooing shoppers to do their shopping early in the day:

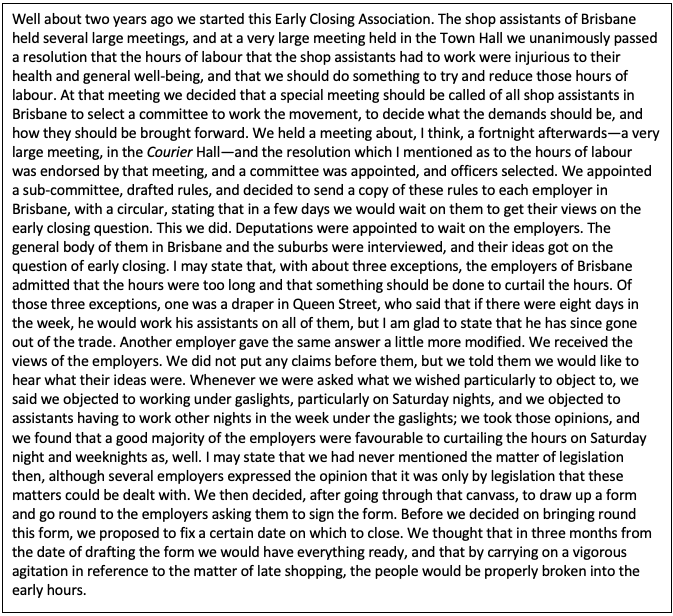

1891 was a significant year for McDonnell. He was, at that time, working as a draper’s assistant with Messrs Edwards and Lamb whilst acting as the Secretary of the ECA. This was also the year the Griffith Government set up a Royal Commission to enquire into the working conditions in Shops, Factories and Workshops. Exploring the issue of early closing was a major question with which the Commissioners were tasked. Whilst the Government selected a number of Commissioners – Basil Moreton Berkeley (Chair), David Hay Dalrymple, Thomas Glassey, Dr James Booth, James Chapman, James Ferguson, John James Kingsbury, William King Salton, Thomas Edgar White, Leontoine Cooper and Grace Neill. After some pressure both the Employers Federation and the Australian Labour Federation were given the opportunity to nominate extra Commissioners. The Employers Federation nominated Alexander Hunter, Thomas Morrow, Robert Woods Thurlow and two businesswomen - Mrs Isabella Isles (widow of James Isles of the drapery company Finney, Isles & Co, and Mrs Elizabeth Edwards (wife of politician and businessman Richard Edward). Frank McDonnell, along with Messrs Thomas William Crawford, James Charles Steward, Mrs May O’Connel and Miss Sarah A Bailey, was nominated by the Labour Federation (Sydney Mail and New South Wales Advertiser,1891, p.421). And, because of his involvement with the ECA McDonnell was also called as a witness by the Commission. Below is an extract from the Report of the Royal Commission wherein McDonnell described the origins of the Brisbane movement for early closing, and a copy of the notice of meeting in 1889:

Early Closing Advocate meeting notice in 1889, from Royal Commission Appointed to Inquire into and Report Upon the Conditions Under Which Work is Done in the Shops, Factories, and Workshops in the Colony – 1891. https://www.austlii.edu.au/cgi-bin/viewdoc/au/other/qld/QldRoyalC/1891/1.html

‘Shop Before 6’, 1889-1986. Acc 27453, Frank McDonnell Papers, ca. 1889 - ca. 1986. Frank McDonnell. John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland.

The Royal Commission sat from February through to May; 1891, interviewed over 370 witnesses, and visited a wide range of shops, factories and workshops in Brisbane and a smaller number in Ipswich. The issue of early closing was canvassed throughout the questioning of witnesses.

In the final reports submitted in June – two of them and a rider - the majority report recommended early closing.

Your Commissioners therefore recommend that 6 p.m. be made, by legal enactment, the hour at which shops should close.

The minority report stated:

We cannot recommend that this legislation should be granted, for the following reasons:

(a) We consider it an unnecessary interference with personal liberty, and therefore objectionable. Avoidable State interference tends to hamper trade and manufactures and to discourage enterprise and self-reliance.

(b) We believe that appeals to the State to undertake those social reforms to accomplish which individuals have hitherto relied upon themselves and the force of public opinion, will rapidly increase if encouraged by such legislation; and undue centralisation, officialism, corruption, and the discouragement of self-help will be necessary consequences.

(c) That compulsory closure of all shops at a stated hour by Act of Parliament is as contrary to the spirit of British freedom as was the curfew law, against which and similar oppressive enactments Englishmen successfully struggled in the past.

(d) We are convinced that it would ruin many small businesses, and that it is not always practicable for our working classes to do their shopping before 6 p.m.

(e) We believe that if restaurants, oyster saloons, soft-drink shops, fruit shops, tobacconist shops, &c., were closed at 6 p.m., the business done in these shops would be catered for by the hotels under more objectionable surroundings, and intemperance would thereby be increased. (Royal Commission Report 1891, pp.974-5).

And Dr Booth’s Rider to the Reports gave support to early closing on the grounds of health and wellbeing:

The medical evidence has abundantly shown that long hours are prejudicial to the health of those working them, and on that ground alone, if on no other, I consider that the State should step in to protect the health of those who now, through trade competition, trade jealousies, public habit, or any other cause whatever, are the victims of a system which cannot but be injurious to body and mind, and I thus recommend State interference, although previous to the sittings of the Commission I was strongly opposed to it. I would also suggest that the administration of any such Act be not left in the hands of the municipal authorities entirely, as in Victoria, but that the people themselves directly concerned, such as the shopkeepers and their employees, should have the power of enforcing it. (Royal Commission Report 1891, pp.971-2).

The Report of the Royal Commission was shelved. The Early Closing Advocate was forced to discontinue when free postage for newspapers was introduced. But agitation continued and McDonnell, who won a seat in 1896 in the Legislative Assembly for Fortitude Valley, made several attempts to introduce Early Closing Bills but failed to get them through. Finally, as Pam Young (1991) records: ‘In 1898, legislation in other colonies met with success, and was not followed by the dire fall-off of trade predicted. Local traders then had a change of heart, and legislation for early closing was finally passed in 1900, to operate from Federation Day, 1 January 1901.’ (Young 1991, p.64).

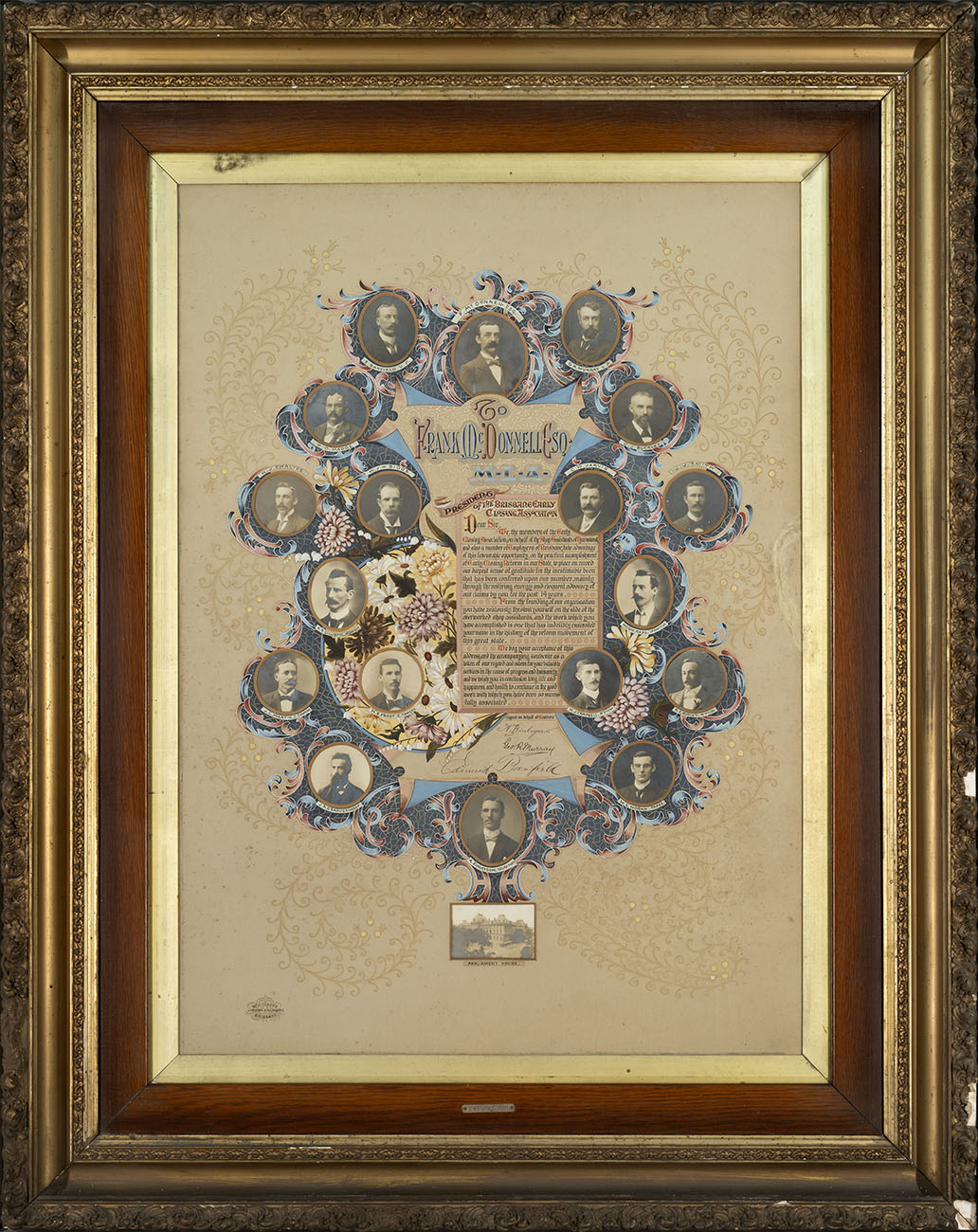

In recognition of McDonnell’s work for the Early Closing movement, this impressive address was awarded to him by the Brisbane Early Closing Association, 25 April 1901.

Illuminated Address presented to Frank McDonnell Esq., MLA, President of the Brisbane Early Closing Association. Presented by the members of the association and by a "number of employers of Brisbane" on behalf of the Shop Assistants of Queensland on the "practical accomplishment of Early Closing Reform in the State" . The address was produced by W.H. Clarke, "Designer and Illuminator Brisbane". Acc 7989, Frank McDonnell Illuminated Address 24 April 1901, (1901), unidentified, John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland.

The address reads:

7989, Frank McDonnell Illuminated Address, 1901, John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland.

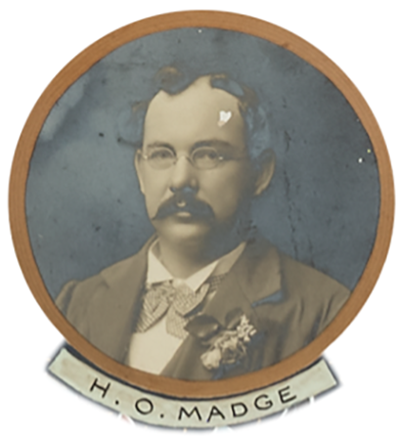

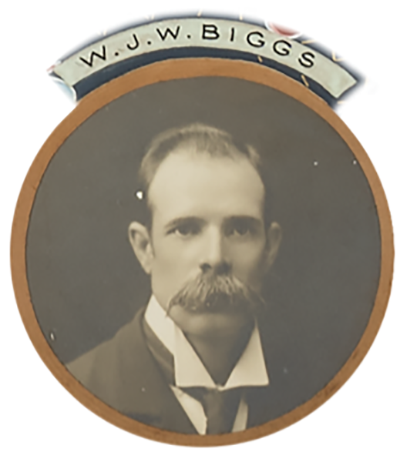

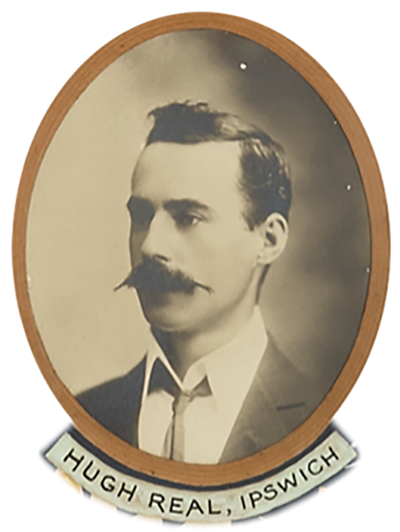

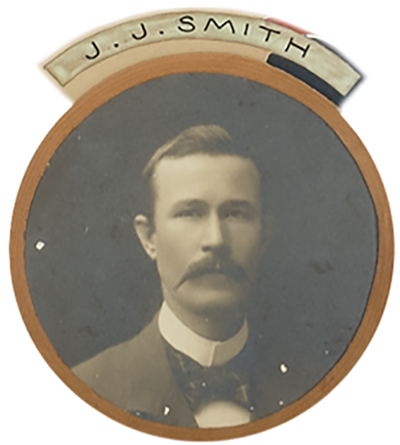

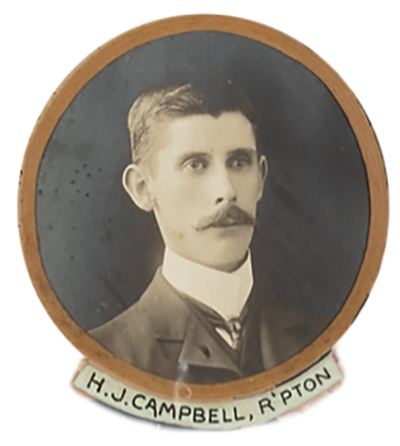

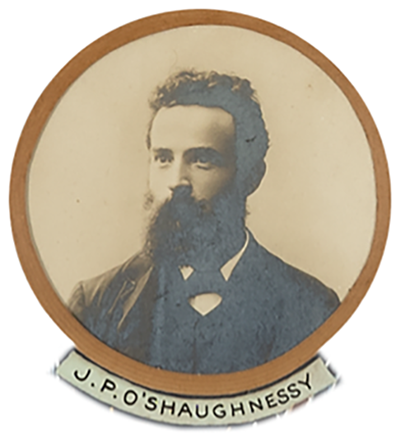

The images below take a closer look at the members of the Association surrounding the address - the Executive, and Committee members from Brisbane and regional groups – as this is also a tribute to their contribution to the Early Closing movement. Notably the Committee was comprised of all men although there were women involved in the movement and the concerns of the movement were for workers in shops and workplaces across the board, i.e. the movement was for all shop assistants – men, women and children.

Frank McDonnell ESQ

E.Banfield V.P.

A.Finlayson, Secretary

W.C.Horan, Treas.

G.R.Murray V.P.

H.J.Chalice

D.J.Buckley

J.C.Martin, C.Towers

H.O.Madge

W.J.W.Biggs

Hugh Real, Ipswich

J.J.Smith

H.E.Frost.C.Towers

C.W.Jarvis

A.R.Gillispie, Ipswich

A.E.Ridley, R'Pton

H.J.Campbell, R'Pton

J.P.O'Shaughnessy

The Address is impressive: richly emblematic of Queensland (by this date now the State of Queensland) and large - approximately 100 x 71cm. It was funded by branches of the Early Closing Association from Brisbane and Early Closing groups around Queensland as well as a number of employers. It is a fitting tribute to McDonnell for an impressive effort to represent and agitate for better conditions for workers in shops, factories and workshops. Whilst his later career in both the political and commercial spheres has been recognised and celebrated, the foundations of a lifetime of valuable contributions to Queensland were laid in his early work for the Early Closing Association.

But let Frank have the last word on this matter. When the Shops and Factories Act 1900 was finally passed he wrote:

The Government and Parliament have done well: they have by their action helped to make the lives of thousands of men and women in Queensland employers and employees brighter and happier. I hope, in conclusion, that this reform is only the first of many necessary ones that the workers of Queensland are anxiously looking to receive from the Parliament of this country

Resources

Read other blogs by Dr Robin Trotter, 2021 and 2024 Queensland Business Leaders Hall of Fame Fellow.

(1) The Early Closing movement to which this story relates is about the struggle for the early closing of Shops, Factories and Workshops to improve the working conditions of shop assistants and factory workers – and not connected to the early closing movement of pubs which was the agenda of the Temperance Leagues. However, when shops and factories did achieve some successes, this did generate the Temperance movement to agitate for 6 p.m. closure of pubs with the objective of limiting the consumption of alcohol.

(2) There were, however, a number of shops supporting the ECM. For example, Finney, Isles & Co. was one of the first shops to introduce early closing and was a regular advertiser in the movement’s journal, The Early Closing Advocate.

A. L. Lougheed, 'East, Hubert (1862–1928)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, https://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/east-hubert-6080/text10413, published first in hardcopy 1981, accessed online 26 April 2024.

Bowden,B. (2011). The Rise and Decline of Australian Unionism: A History of Industrial Labour from the 1820s to 2010. Labour History, 100, 54. https://doi.org/10.5263/labourhistory.100.0051

Cross, M. (2008). The eight hour day in Queensland. Labour History Journal, No. 6, March.

Lavis, J., 1986, ‘The Hon. Frank McDonnell: Champion of Women’, Unpublished thesis, University of Queensland.

McDonnell, F. (1901, January 11). Factories and Shops Act, Brisbane Courier, Fri,p.2.1

M. R. MacGinley, 'McDonnell, Francis (Frank) (1863–1928)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, https://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/mcdonnell-francis-frank-7343/text12747, published first in hardcopy 1986, accessed online 26 April 2024.

Rottenberg, S.(1961). Legislated Early Shop Closing in Britain. The Journal of Law & Economics, Oct., Vol. 4, p.118-130.

Royal Commission Appointed to Inquire into and Report Upon the Conditions Under Which Work is Done in the Shops, Factories, and Workshops in the Colony – 1891. https://www.austlii.edu.au/cgi-bin/viewdoc/au/other/qld/QldRoyalC/1891/1.html

State Library of Victoria. (n.d.) Fight for retail hours. https://ergo.slv.vic.gov.au/explore-history/fight-rights/workers-rights/fight-retail-hours

‘Queensland, Brisbane, Thursday: A Proclamation has been issued …’, 1891, Sydney Mail and New South Wales Advertiser, Saturday, 13 February, p.5.

Unidentified.(1892, November 30). The Early Closing Association, Brisbane Courier, Wed, p.7

Whitfield, G. (1969). Industrial Conditions in Early Queensland: Reports of the 1990s. Queensland Heritage, Vol.1(10), p.20-23.

Young, P. (1991). Proud to be a Rebel: The life and times of Emma Miller. University of Queensland Press, St Lucia, Queensland.

Dr Robin Trotter's Research Reveals talk.

Comments

Your email address will not be published.

We welcome relevant, respectful comments.