Flu pandemic 1919: “the enemy at the gates”

By Stephanie Ryan, Research Librarian, Information Services | 1 December 2020

The flu pandemic became apparent in Europe in 1918 as the war was ending. Young Australian soldiers relaxing and recovering after the Armistice on 11 November wrote their Christmas cards home but some suddenly sickened and died. Their families were distraught as they had felt assured, at war’s end, that they would see their young men soon. The flu pandemic reached Australia, it is believed, with returning soldiers. It has been said that these soldiers formed the largest mass movement of people since the gold rushes and they were doing so in confined spaces, perfect for spreading disease.

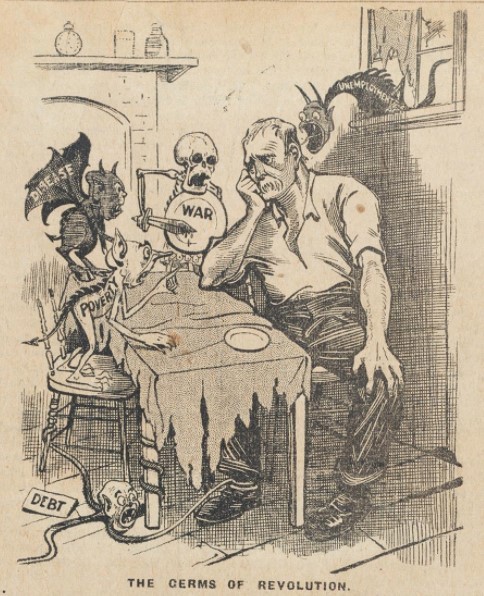

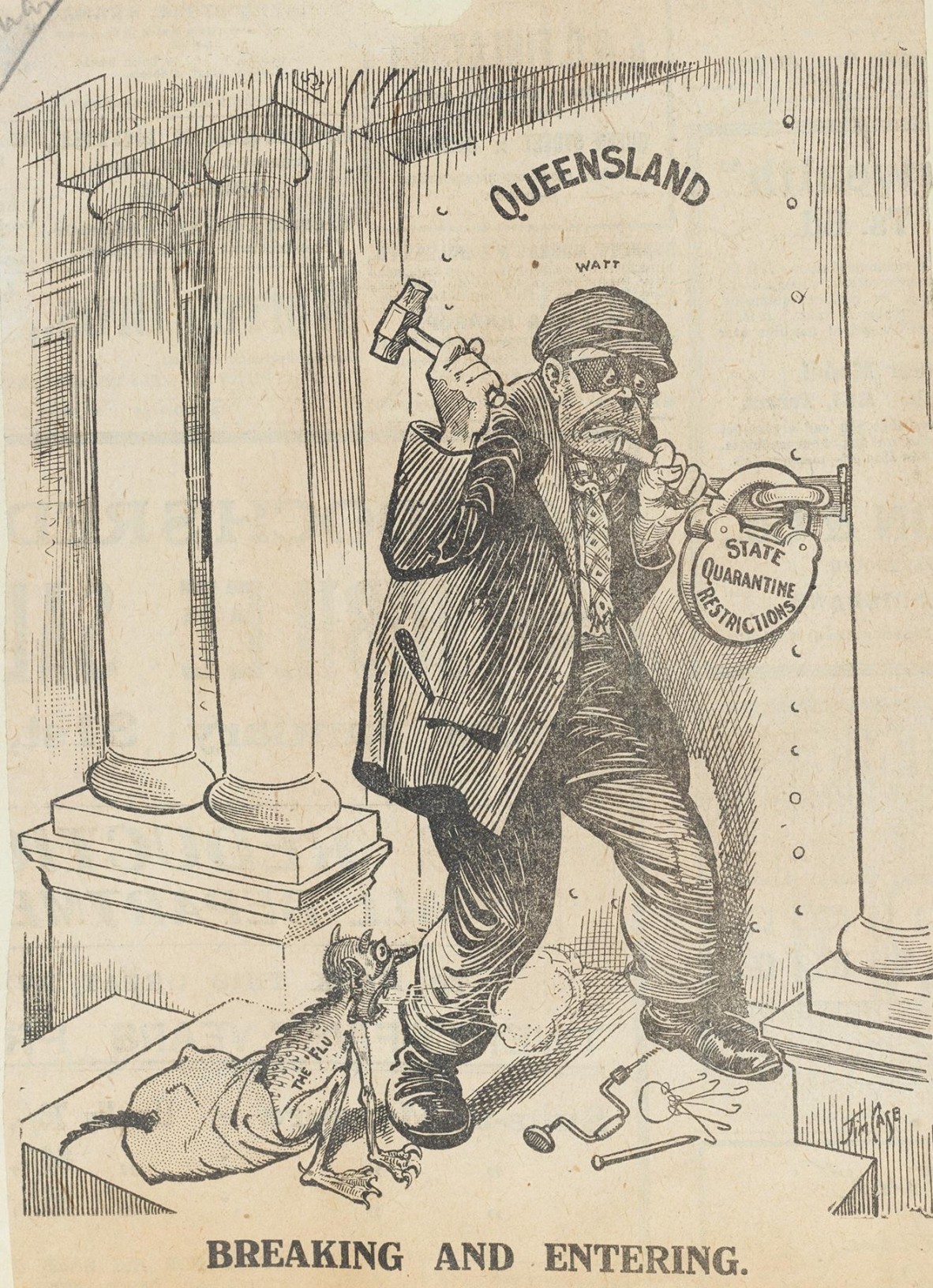

This cartoon points out that the flu epidemic in the post war world was made worse by unemployment, debt and poverty. The flu was presented dramatically in cartoons as a devil, a demon, a thief, an overpowering warrior or the grim reaper. The political cartoon was a favourite tool for the press to distil a succinct, political point powerfully.

In November 1918, the Commonwealth and State Governments, now aware of the virus and its deadly implications, met to plan action. The Commonwealth Government needed to take overarching control, and by January 1919 the virus had reached Australian shores.

New South Wales identified its first victim on 22 January, a returning soldier, who had been in the community for enough days for the virus to spread rapidly. As he had disembarked in Melbourne, it was seen that Victoria was not being sufficiently vigilant or honest, so state borders snapped shut.

The flu spread on public transport and in groups of people. At that time, trains and ships were the main means for interstate movement of people, goods and mail, not cars or planes; they were also where people congregated closely.

Queensland’s position: closed borders

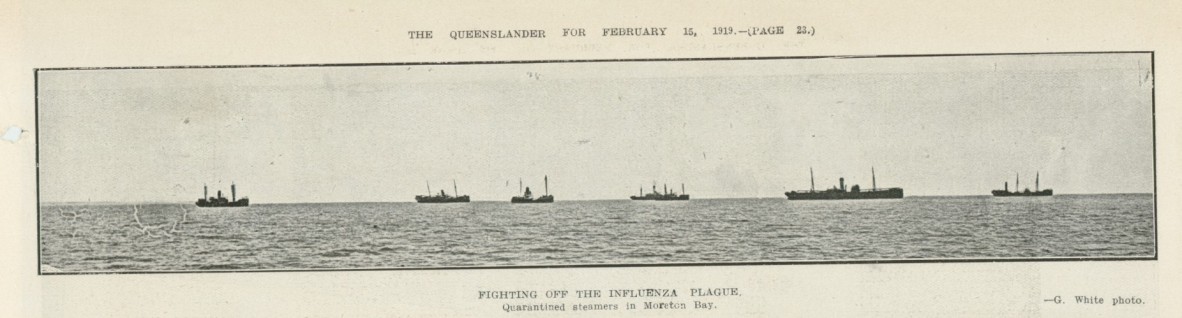

Queensland had been desperate to remain a “clean state”. Maritime quarantine saw ships lined up in the bay. The State Government wanted maritime quarantine off the mainland at Bulwer, Moreton Island so that there would be no likely escapees among the returning soldiers. The Commonwealth Government held firm on Lytton, on the mainland.

Fighting off the influenza plague: quarantined steamers in Moreton Bay. Queenslander, 15 February 1919, p 23. State Library of Queensland.

While the Commonwealth Government retained responsibility for maritime quarantine and immunisation under the Director of Quarantine, Dr J H L Cumpston, the states managed their own preventive measures and guidelines. New South Wales trains were stopped at Tenterfield when the Queensland borders closed quickly. There were numerous images of “marooned” Queenslanders, including those depicted in ‘Influenza on the Queensland border’ (Sydney Mail, 26 February 1919, p 16), showing the Coolangatta-Tweed Heads quarantine camp and the Tenterfield camp ‘Battling Against Pneumonic Influenza’ (Queenslander, 22 February 1919, p 28).

Quarantine for Queenslanders

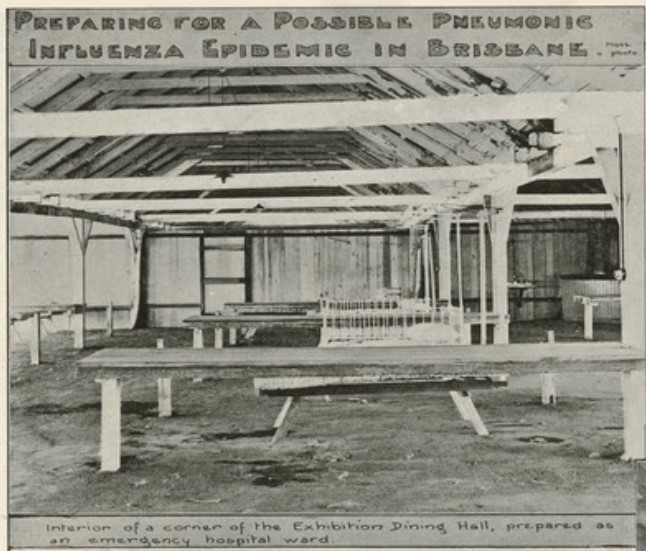

Lytton became the focus for quarantine in Brisbane, as shown in the series of pictures ‘In Quarantine at Lytton’ (Queenslander, 29 March 1919, page 26), but further preparation was considered necessary as seen below.

Preparation for the Spanish Flu in Brisbane. Queenslander Pictorial, supplement to The Queenslander, 1 March 1919, p 25.

This was one of the few times the Exhibition was cancelled. Instead, the Exhibition building became part of the quarantine arrangements.

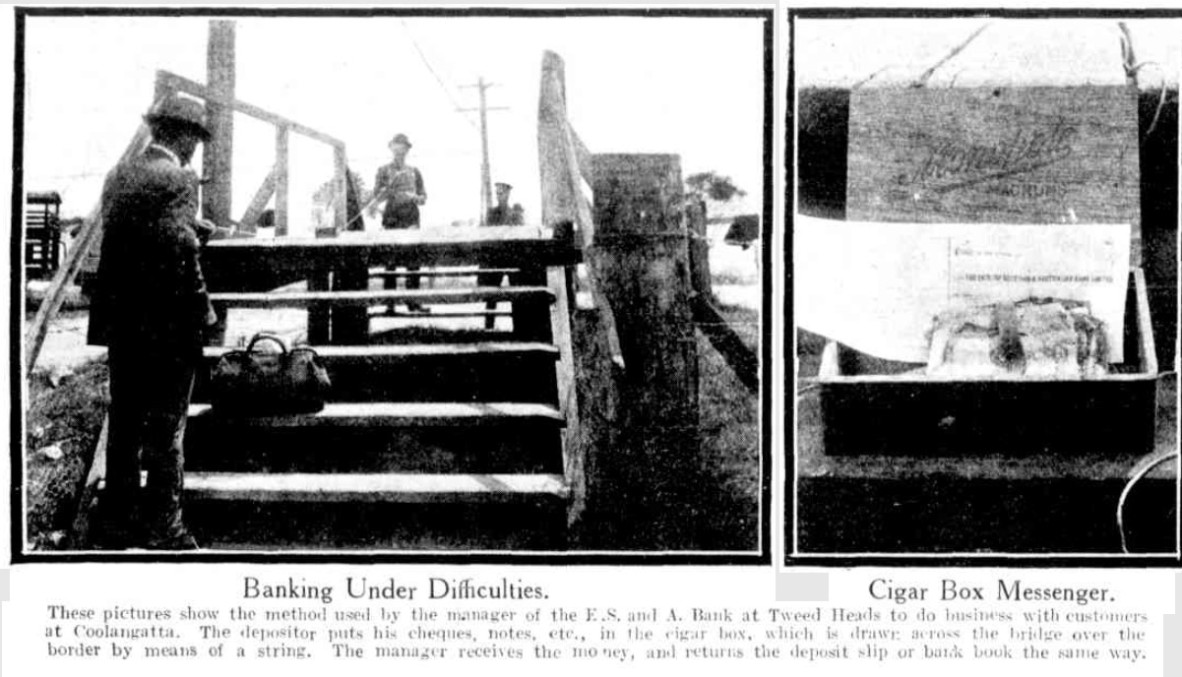

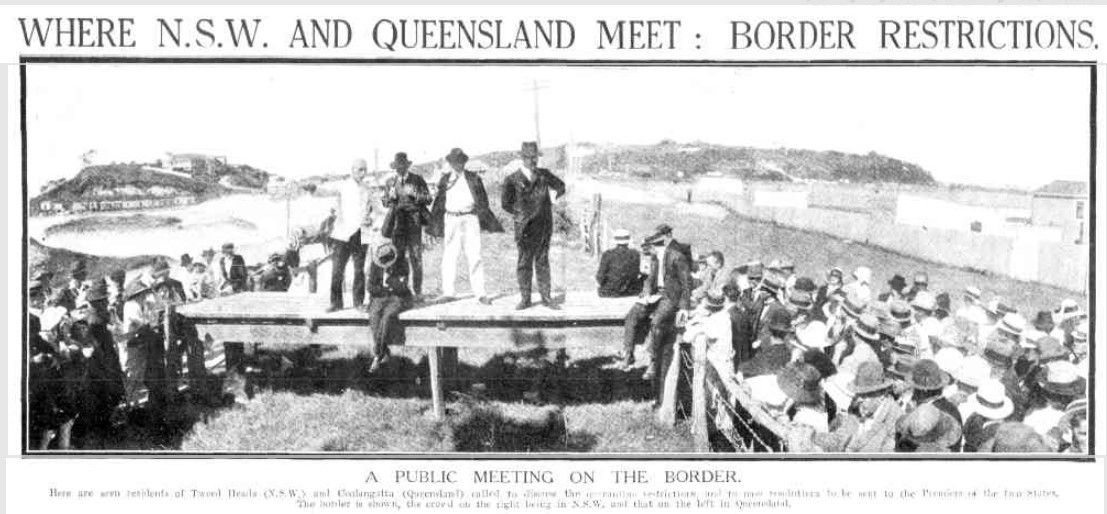

Many Queenslanders, trapped on their way back from their summer holidays, were caught by the sudden border closure. Coolangatta and Tweed Heads were effectively one settlement with most services in Tweed Heads on the New South Wales side, so some innovative and amusing adaptions to the situation were required. The humorous and unfortunate situations were not lost on newspaper photographers, as shown in ‘Serio-Comedy at the border Quarantined at Tweed Heads’ (Queenslander,15 February 1919, p 22) or the Daily Mail’s ‘Tragi-Comedy at the Tweed’ (15 February 1919, p 14). Other examples appear below.

A cigar box, moved across the bridge by string, was used to carry out what would have been an over-the-counter banking transaction. Sydney Mail, 19 February 1919, p 10.

Residents of Tweed Heads (New South Wales) and Coolangatta (Queensland) were called to discuss the quarantine restrictions, and to pass resolutions to be sent to the Premiers of the two states. The crowd on the right was from New South Wales and that on the left in Queensland. Sydney Mail, 19 February 1919, p10.

The northern border

On the northern Queensland border, Torres Strait Islanders were inoculated. Some Aboriginal settlements suffered among the worst rates of contagion and death.

First official flu death in Queensland

The first person in Queensland to die from the flu officially was John Elliott Fitzpatrick, crewman on the coastal vessel Gabo. He was 32 and, like many victims such as soldiers, he was male and in the vulnerable age group 20-40. In Sydney, he had a wife and two children, aged three and five. He was buried in the cemetery of the Lytton quarantine station, and the three death notices in the Sydney Morning Herald indicate that, as in so many instances, a wide circle of family members was affected.

Both the press and the general public supported the Queensland Government when there was conflict with the Commonwealth.

By 1920 the flu was drawing to an end. The official death rate was far greater than it has been so far in the COVID-19 pandemic, but even so it is believed that the figures were incomplete. Dr Cumpston, the Director of Quarantine, was strongly committed to public, preventive medicine. He saw the study of epidemiology with an emphasis on the history of disease as an important dimension. There is plenty of information about the 1919 flu both from the medical and social perspectives accessible in the media of the day. Today we can look back on the 1919 pandemic with a sense of familiarity in relation to preventive measures from border, maritime and community quarantine to issues of the balance of health and economic importance as well as the tussle between Commonwealth and State Governments.

More information

One Search - http://onesearch.slq.qld.gov.au

Comments

Your email address will not be published.

We welcome relevant, respectful comments.