Writers are always collecting. Ideas for stories, poems, and books can come from anywhere. Things writers see or touch or read can return – sometimes unexpectedly – in the future to inspire them.

State Library is filled with treasures and curios. In this new series, we invite authors to find an item in our collections that inspires them to write a new, original creative piece of work.

Jarad Bruinstroop is an award-winning poet based in Brisbane. His first book of poetry, Reliefs, was published in August and went on to be shortlisted for the Judith Wright Calanthe Award for a Poetry Collection.

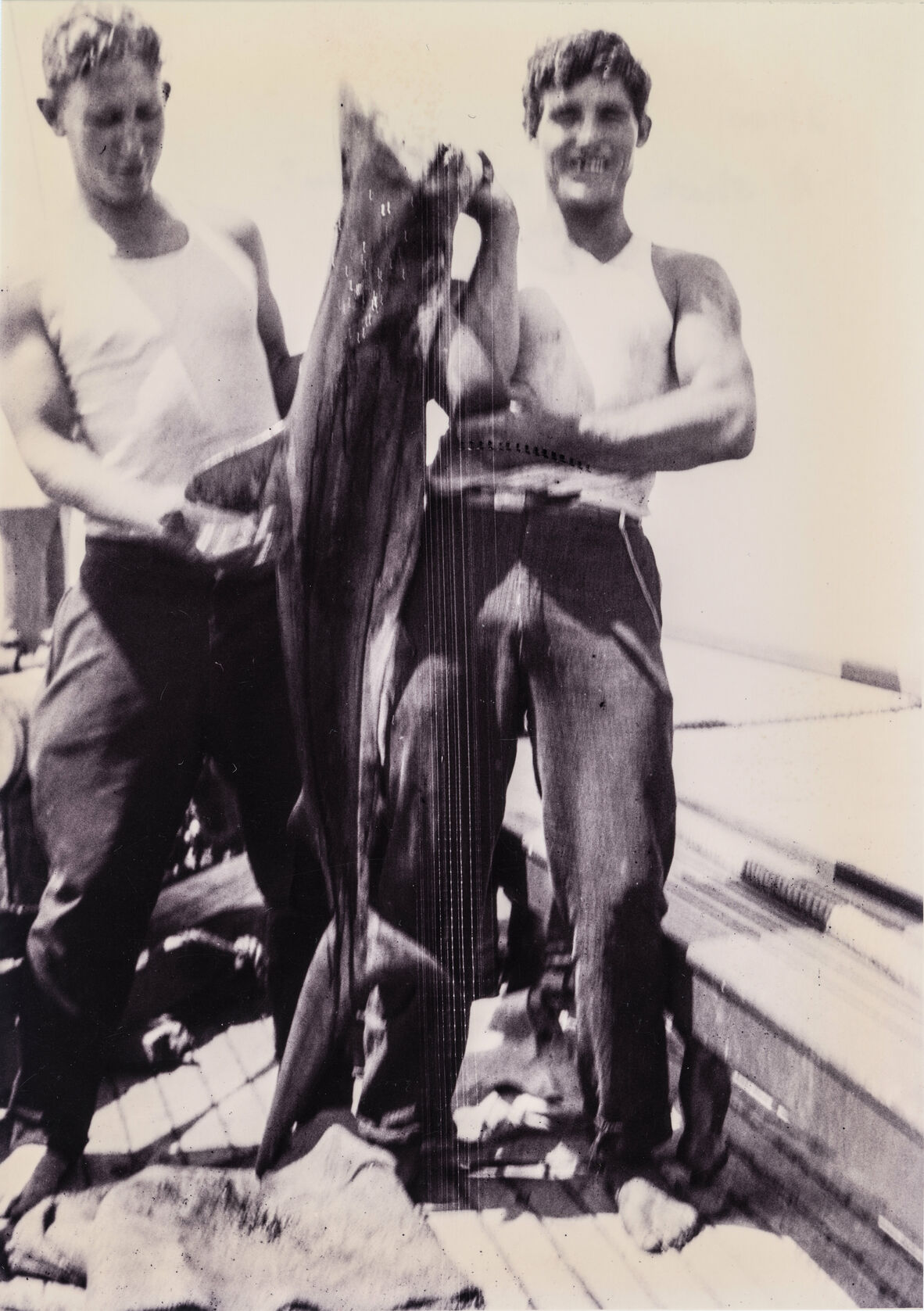

In 2024 Jarad won a prestigious Queensland Writers Fellowship to work on his first novel set in Queensland during World War 2 (it's going to be brilliant and we can't wait). Jarad went looking in the John Oxley Library collection and was enchanted by a photograph of a pair of men on a beach. Not a perfect photo, as Jarad explains, but one that inspired a beautiful piece of short fiction called 'Fishing'. It's a piece that suggests loss and threat, menace and love.

Read 'Fishing' and the story behind it below. Thank you to Jarad!

Jarad launched his debut Reliefs at Avid Reader in August 2023.

"I love the mysterious black and white photos in the John Oxley Library collections that hint at past lives we can’t really know. I was especially drawn to this blurry and poorly composed image that barely captures a charged and fleeting moment. The fact that I don’t know much about the photo is exactly what makes it generative.

"I found this image searching State Library's online catalogue after a news story about the 25th anniversary of the federal government protecting the great white shark got me thinking about the history of shark-settler relations in Australia.

"2024 was a year of loss for me (and so many others) but I haven’t yet been able to address this in my writing. The themes of ephemerality and death discernible in this image allowed me to begin to consider how my grief and my gratitude might find expression."

I love the mysterious black and white photos in the John Oxley Library collections that hint at past lives we can’t really know.

Low Isles, off the coast of Port Douglas on the Great Barrier Reef, was the site of a significant scientific expedition in 1928, when this photo was taken.

'Fishing'

by Jarad Bruinstroop

The first afternoon of our holiday, on the beach in front of our hotel, my boyfriend and I walked into a fishing line that was floating down the foreshore like a broken spiderweb. The line belonged to three boys who paid us no attention as we untangled ourselves. How stupid, I thought, to stand on the sand and cast their line where everyone was walking instead of a few steps forward in the water, out of the way. The boys looked twelve, maybe a little older. Two were the same height and build, but the third was shorter and still carried some puppy fat.

An hour later when we passed them on our way back, I was careful to walk behind them. A man standing there said, ‘They’ve caught a shark.’ The man had grey hair and the same thick kiwi accent as Gerry. That’s what I’ve been noticing since he died — his accent. Every so often I hear men talking with Gerry’s voice. It happened with the plumber who came to fix the shower a few weeks back and then the other day with a man on TV who was being interviewed about pomegranate farming.

My boyfriend and I turned to watch the boys.

One of them was intently reeling in something that would not come in from the shallows. My boyfriend gasped.

‘Did you see it?’ he asked.

If this were a poem, I would have to cut my boyfriend out because he is not the subject of the piece. It would just be me watching the boys alone, only me and the man who sounded like Gerry. But because it is a short story he can stay; there’s room. I’m sure I’ll find something for him to do.

‘Not yet,’ I said. I dug in my pocket and swapped my sunglasses for my plain glasses and the world became bright and clear.

The boy with the fishing rod kept letting out a little bit of line and then furiously reeling it back in. The pole was bent with the strain of what he had caught trying to escape.

‘I’m hooked,’ said my boyfriend. ‘Can we stay?’

I stared at the whitewater about where I thought the line must end but I couldn’t see anything.

‘There.’ My boyfriend pointed. Suddenly, a fin flashed out of the water, followed by a swinging tail that quickly disappeared.

It was hard to tell how big it was, but it wasn’t full-grown. Maybe an adolescent. The boy continued to struggle. His mate waded gingerly into the water and heaved on the line. He created slack behind him and the other boy wound up the reel. The shorter boy was sort of hopping about them like a small dog.

I wondered if they were friends or brothers or cousins. Gerry had a brother, a twin who looked only a little like him.

‘That’s the trouble with fishing,’ said the man with Gerry’s accent. ‘Sometimes you catch something and you don’t know what the bloody hell to do with it.’

I laughed to show him I didn’t mind strangers talking to me and that we — he and my boyfriend and I — were all together in this experience of watching the boys fight the shark.

The whole scene reminded me of The Old Man and the Sea which is my only real experience of fishing. I was once forced to try fishing in Scouts, but I couldn’t bring myself to pierce the worm with my hook, so I just pretended and dipped the empty line off the jetty to predictable results.

Anyway, these were not old men, they were young boys.

The man said, ‘It’s a shame no fishermen are around to show them what to do.’

Even so, the two taller boys managed to get the shark close enough to shore for us all to see. It was thrashing every which way as if it didn’t understand that it was caught. The shark was only small but perfectly formed and a uniform grey colour all over like a dolphin. The second boy walked further in and stood near to where the shark was writhing in the surf.

‘Careful,’ my boyfriend called out.

Slowly, slowly the boy with the fishing rod was winning. He drew the shark closer. His mate leant down and grabbed the shark’s tail, but it squirmed away. Not fully-grown, but it could still do some damage. He lunged for it again and this time found his grip. He dragged the creature onto the beach where it flailed about. It wasn’t going out easy.

The boys tried to pull the hook from the shark’s mouth, but they couldn’t get near it. After a while, the shark went still and the boys approached, but then it reanimated and the boys leapt back beyond its reach. The fish stilled again and they went back to their task. Two of them held the shark down while the other worked the hook out of its flesh. Every so often it would spasm then stop. As we watched, the intervals became longer. Even I could see its gills, puckered and unmoving.

‘It needs to go back in the water,’ my boyfriend said.

Finally, the kids wriggled the hook free. Then the two tall ones heaved the shark up in front of them so the third could take their picture, but it was deadweight and slippery and they dropped it. The shark smacked onto the sand. The boys hauled it up again and the shorter boy took the photo and then held his phone in front of him to take a selfie with his mates and the now motionless shark behind him. He pulled a silly face.

“It’s time, fellas,’ said the man with Gerry’s voice. I suppose it was the accent not only of a place but of a particular kind of man, the kind who talked to strangers and who knew how to fix a leaking shower and how best to grow pomegranates in an inhospitable climate. The kind of man who, when time was up, said so.

I watched as the shark was lowered back into the shallow water where it floated parallel to the shore like a log. We all waited to see if the shark would start to swim again. It was taking too long, I thought. It had been out of the water for too long and now it couldn’t come back. The kids had—

‘It needs to face into the waves,’ my boyfriend said. ‘That’s how they breathe, with water flowing through their gills.’

One boy got on either side of the shark and they nudged it until it was facing out to sea. The water lapped over the perfect grey form, and it started to shift away from the shore, but it was hard to tell if it was swimming or being carried out by the tide.

Then it was gone. The boys were looking at their phones and the man strolled away and it was getting dark and the lights came on in the hotels above the cliffs and my boyfriend and I walked together down the beach towards whatever comes next.

Low Isles is part of Yirrganydji Country in North Queensland. The 1928 expedition collected data about coral and tides and studied the reef's biological and geological life. The research party included women scientists, unusual for the time. Find more photos online at State Library.

Jarad Bruinstroop’s debut poetry collection, Reliefs (UQP, 2023) won the Wesley Michel Wright Prize, the Thomas Shapcott Poetry Prize, and was shortlisted for the Judith Wright Calanthe Award and the Five Islands Poetry Prize. He is the recipient of the Val Vallis Award, the Queensland Writers Fellowship, and the Fryer Library Creative Writing Fellowship. His work has appeared in The Best of Australian Poems, Meanjin, Overland, HEAT, Island, Westerly and elsewhere. He holds a PhD in Creative Writing from QUT where he now teaches.

Comments

Your email address will not be published.

We welcome relevant, respectful comments.