Electric city : trams and power in Brisbane

By Simon Miller, Library Technician, State Library of Queensland | 21 July 2014

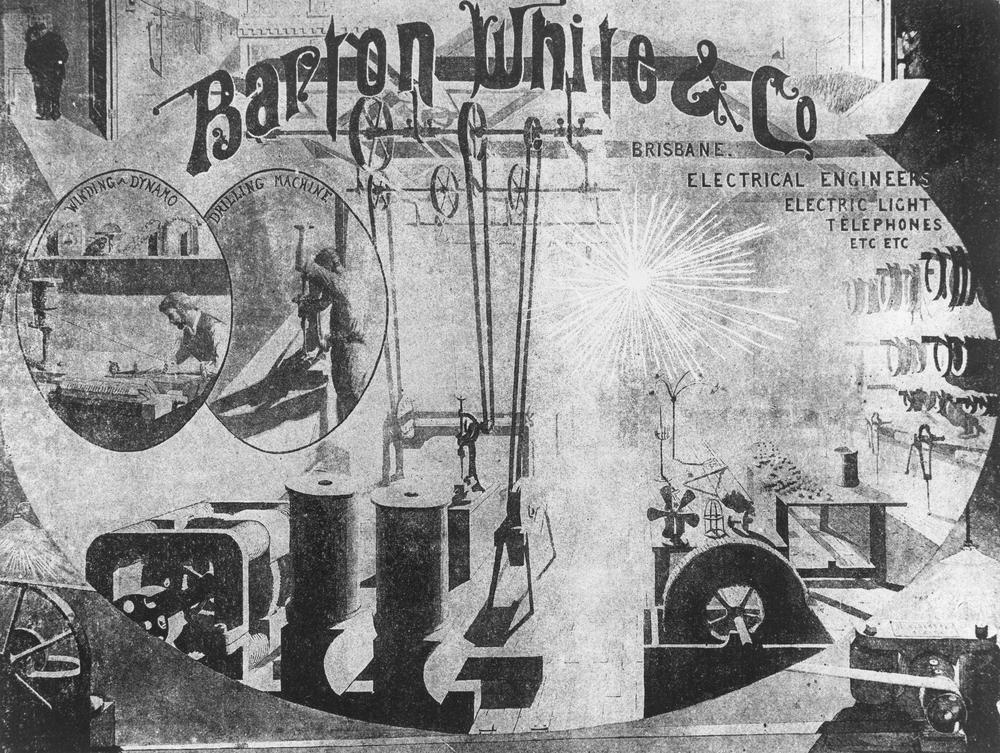

Brisbane in the nineteenth century was in many ways a primitive, frontier town with unpaved streets and an unreliable water supply but in other ways it was in the forefront in adopting new technology. I have previously described Brisbane's early and enthusiastic adoption of the new telephone technology. The Brisbane Gas Company was incorporated in 1864 to supply gas for street lighting and domestic and commercial purposes which it manufactured from coal. Gas lighting soon had a competitor in the form of electricity. The world's first public electricity supply was delivered in Godalming, Surry in 1881 and Thomas Edison opened the world's first steam driven electricity generation plant in London in 1882. The first public electricity supply in Brisbane followed less than a decade later in 1888 when Barton White & Co. was contracted to provide electricity to the G.P.O. from their building in Edison Lane. Brisbane was not the first Queensland town to have established electric street lighting however, that honour went to Thargomindah in the west of the state.

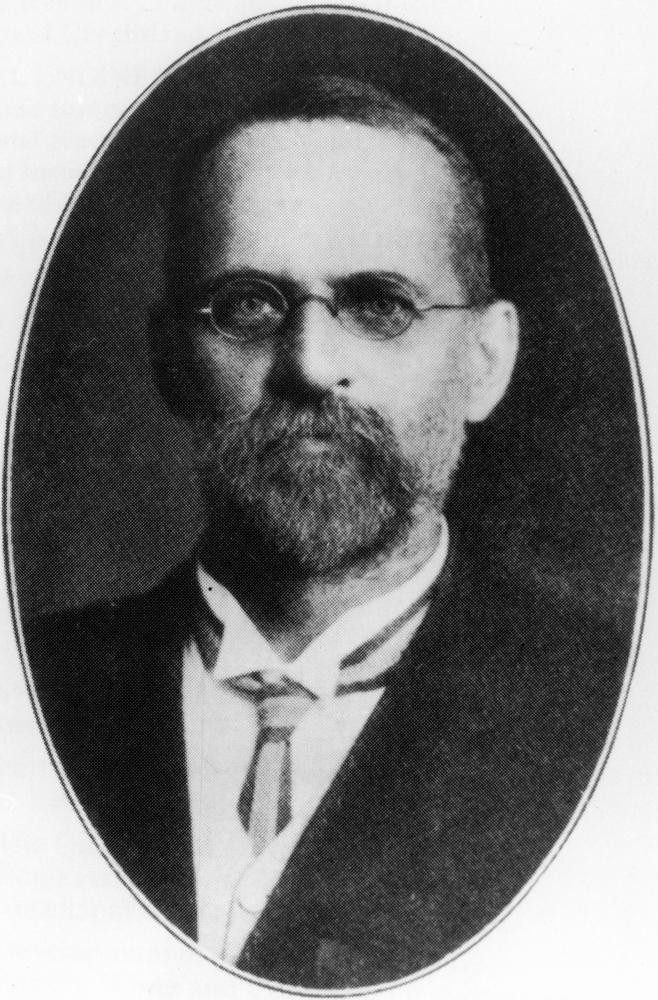

C. Frank White was one of the first electricians in Queensland, taking up the agency for the American Edison Company around 1881 and operating as an electrician and electrical supplier from a shop in Creek Street before forming a partnership with Edward Barton in 1888 with financial backing from his brother Thomas. Edward Gustavus Campbell Barton was a pioneer of the electricity industry, having supervised the first commercial electricity supply in Godalming in 1882. After working as an electricity consultant in New Zealand and Australia, Barton was engaged by the Queensland Government to complete the installation of electric lighting equipment in the Government Printing Office and parliament buildings in 1886 and was appointed Government Electrician.

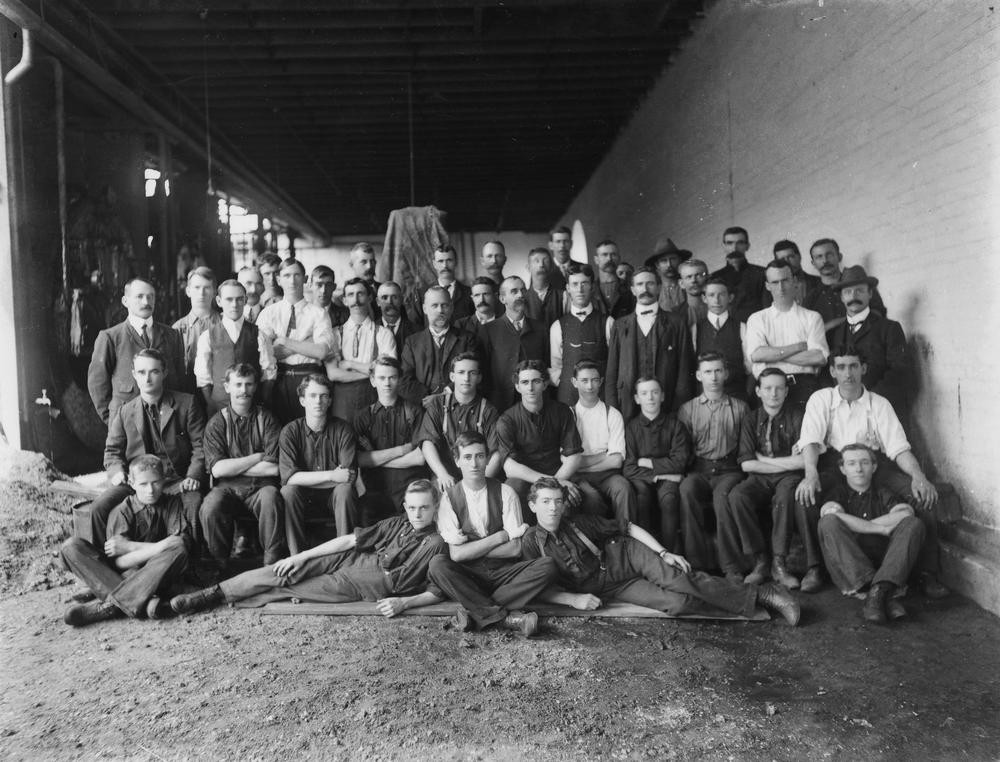

The depression years of the 1890s proved to be a tough time for developing a new industry. Uptake of electric power was slow and running cable over the roofs of city buildings was expensive. The Queensland Government was slow to respond to the new technology and the first legislation for the control of electricity supply was not enacted until 1896. Transmission of electricity by overhead cables was illegal until 1898. In 1896 Barton, White & Co. was declared insolvent and the partnership was dissolved. Barton formed the Brisbane Electric Supply Company to carry on the business. The original powerhouse in Edison Lane was abandoned in 1898 and a new powerhouse opened at 69 Ann Street. A unique personal perspective on the early development of the Brisbane electric industry comes from F. R. L'Estrange who's presentation to the Post Office Historical Society on Brisbane's early electricity supply was published in 1954. L'Estrange joined the company as a 14 year old apprentice in 1904. In that year the company was renamed the City Electric Light Company.

In the mean time another player had come on the scene. Since 1885 the Metropolitan Tramway and Investment Company had offered a horse-drawn tram service in inner Brisbane from Albion Park and New Farm to West End and Buranda under the Tramways Act of 1882. An amendment to the Act in 1890 allowed for the sale of the company and electrification of the line. The 20 miles of track and 51 cars were sold to the Brisbane Tramway Construction Company, the owners also registering the Brisbane Tramways Company to operate the electric trams. American company General Electric were chosen for the task of electrifying the tramways and Joseph Stillman Badger was sent out as Chief Electrical Engineer to oversee the work. Badger would stay in Brisbane until 1922, transfering from GE to work directly for the Brisbane Tramway Company as Manager, then General Manager and ultimately Managing Director.

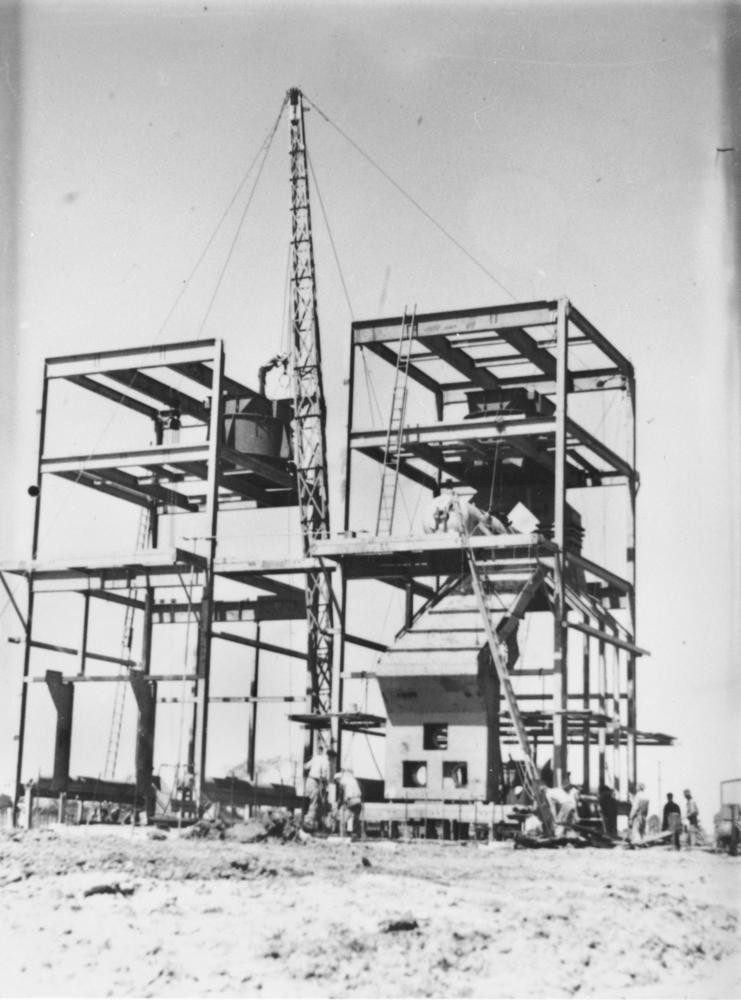

To provide the electricity supply for the trams a new powerhouse was built on land at Countess Street bordering the Roma Street goods yards. Three Robey cross-compound, horizontal, non-condensing, steam engines were installed, each driving a 300 kW, 550-volt DC generator. The engines were supplied with steam from four large boilers under a 150 ft. high brick chimney. Alongside the powerhouse, additional land provided space for the offices and workshops for tram maintenance and manufacturing. In 1902 the installation of more powerful generating equipment meant that the tramways now had excess power which could be sold off to homes and businesses adjoining the tram lines.

As well as distributing electricity the tram service had an important role in distributing mail. This began in the horse tram era when the trams were contracted to transfer mail between the G.P.O. and suburban post offices at Breakfast Creek, South Brisbane and Woolloongabba. This arrangement was continued and expanded when electric trams were introduced and continued until 1934. As well as transferring mail between post offices the trams also served as mobile post boxes with posting bags being carried on trams from 1894 until 1916.

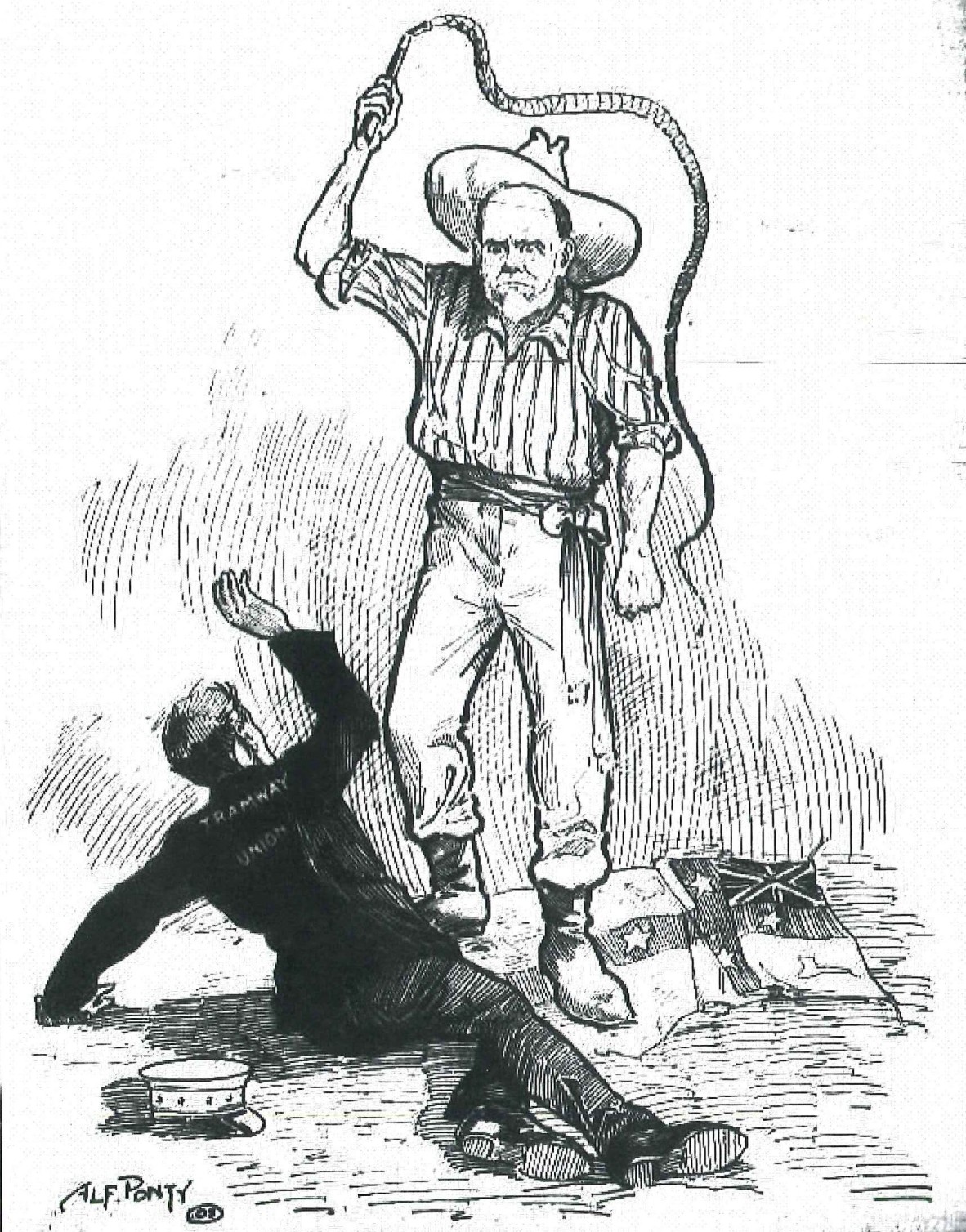

Described in the Australian dictionary of biography as able, courageous and ruthless, Joseph Badger oversaw the expansion of the tramways into a profitable company able to pay handsome dividends to its stockholders. He was implacably opposed to trade unions and his hard line approach led to the General Strike of 1912 after union members were locked out for wearing union badges on their uniforms. The Labor Party remained hostile to Badger and when a Labor government of T. J. Ryan was elected in 1915 they began planning a government takeover of the tramways.

The government put plans in place to buy out the Brisbane Tramways Company and at the same time sought to limit the company's profits by legislating to control fares in a bid to reduce what they would ultimately have to pay for the company. At the same time they raised doubts about the legality of the company's electricity supply sideline. The government did not want to have to compensate them for their electricity distribution assets as well as their core tramway business. The Tramways company's electricity distribution assets were sold to the City Electric Light Company in 1921 when the company realised that its aging generating equipment limited its capacity. Conflict between the government and the company continued with the government attempting to devalue the company and refusing to include tramlines it claimed were built without permission. The company struck back with its London based investors urging a boycott of lending to the Queensland Government. In the meantime the company refused to invest in new lines or equipment and the network was becoming run down. Eventually a compromise valuation was agreed and the company was purchased by the Brisbane Tramways Trust before being handed over to the newly formed Brisbane City Council in 1925.

The City of Brisbane Act of 1924 created what is often known as Greater Brisbane from two former Cities, seven towns, ten shires and parts of two other shires. Section 36 of the Act gave the city council the authority to generate electricity for light and power. The only generating capacity in the control of the council was that of the tramways which had three small and obsolete power stations in Countess Street, Light Street and Logan Road. Much of the city was already being supplied with electricity by City Electric Light Company. The Council had to decide whether to continue buying electricity from CEL or to go into competition by generating its own electricity. Firstly, however, the council decided to try to purchase the City Electric Light Company. The council had turned down the opportunity to purchase the company when Barton & White was declared insolvent in 1894 and on a number of occasions since the idea had been put forward but no agreement had been reached. In 1926 the council made an offer to by the company's assets for £1,500,000 but the company was not impressed, making a counter offer to sell at £2,500,000. The distance between the two parties proved to be too great and the BCC resolved to build their own power station.

The New Farm Power Station was opened in 1928 with two units generating less than 10,000 kW although the capacity would rapidly increase. The new power station was controlled and operated by the council's tramways department, supplying in bulk to the electricity department, the tramways and the council's workshops. The bulk supply required by the tramways was essential as the council was unable to supply the industrial and commercial customers in the city centre which were supplied by CEL under franchises it owned under the terms of the 1896 Electric Light and Power Act. City Electric Light had opened its new Bulimba power station in 1926.

The existence of two major power stations in Brisbane where one would have been sufficient was just one example of the inefficiencies that had developed as a result of the piecemeal and patchy development of electricity generation and supply throughout Queensland and in 1936 the Queensland Government established a Royal Commission on Electricity chaired by J.R. Kemp, the Main Roads commissioner and a well qualified civil engineer. The commissioners gave their prime attention to 'ensuring the orderly planning of the electrical supply industry in Queensland', to the elimination of waste and duplication, to the economic development of the state, and to rural electrification. The end result of the Royal Commission's work was the formation of the State Electricity Commission. They undertook to implement a scheme for the electrification of south-east Queensland with the City Electric Light Company playing a leading role with a plan for the government to purchase the company in 15 years time.

Eventually instead of the government purchasing the company a compromise was reached. The company was converted from a privately owned company into a public authority under the Southern Electric Authority Act of 1952. The company's directors would remain in charge, supplemented by the electricity commissioner and an official from Treasury. There would be no cash payment and the shareholders would have their investments converted into stakes in a public loan. In 1962 a further rationalization occurred when agreement was reached for the Brisbane City Council to relinquish its power stations and instead take over electricity distribution for the whole Greater Brisbane area.

The ownership of Queensland's electricity generation and distribution infrastructure remains a contentious issue with moves by the current government to privatize parts of the network generating a lot of discussion and conflict.

A very thorough description of this history can be found in A history of the electricity supply industry in Queensland by Malcolm I Thomis. The story of Boss Badger and the Brisbane trams can be found in One American too many by David Burke. The last Brisbane trams ran in 1969 when they were replaced with buses, however trams are making a return to south east Queensland with a new light rail service carrying its first passengers on the Gold Coast this week. See an album of Queensland trams on SLQ on Flickr.

Simon Miller - Library Technician, State Library of Queensland

Comments

Your email address will not be published.

We welcome relevant, respectful comments.