Drama on the high seas: the shipboard diary of Margaret Gray, 1883

By Dr Allison O'Sullivan, 2020 John Oxley Library Honorary Fellow | 3 March 2021

Guest blogger: Dr Allison O'Sullivan - 2020 John Oxley Library Honorary Fellow.

If you're interested in the hearing more stories from the diaries of Women living in colonial Queensland don't miss Dr Allison O'Sullivan's Research Reveals talk on the 9th February 2022, 6pm, Auditorium 1. BOOK HERE for onsite tickets. This event will also be livestreamed on State Library's Facebook and Live Stream webpage.

On 12th September 1883, Mr and Mrs Patrick Gray and their four daughters boarded the Berwick Law in Glasgow to begin their journey to Brisbane. Mr and Mrs Gray were given quarters in the married couples section of the ship, and the girls were housed in the single women’s dormitory, which was run with the discipline of a boarding school. Their daughter Margaret began her shipboard diary on September 15th.

A journey on a ship in 1883 was not as we would experience it today, and the girls were responsible for much of the work below decks, including their own cleaning, laundry, and sewing, table service and washing up at mealtimes, scrubbing the dining room, and baking desserts.

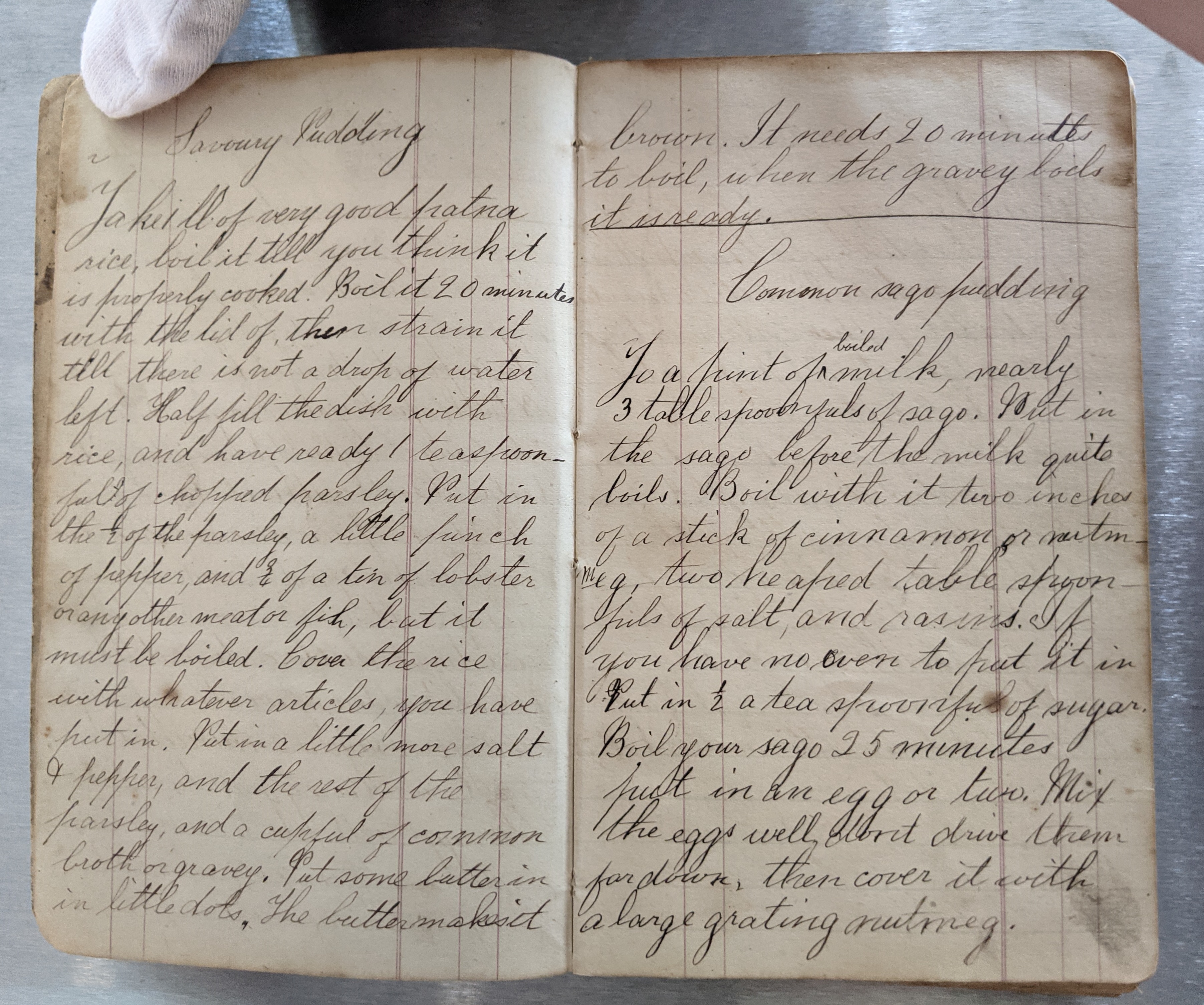

Margaret’s diary begins with a series of handwritten recipes, possibly copied down for use on board. Her early entries describe the seasickness of everyone on board, and how this affected their meals, chores, and exercise. Breakfast on the 15th was a sorry affair, and dinner even worse. While Margaret was not the worst affected, she still notes that of their meal of soup, meat, and potatoes “my last bite came up.” Margaret and two others were quite sick until “we got our dinner up and I got better.”

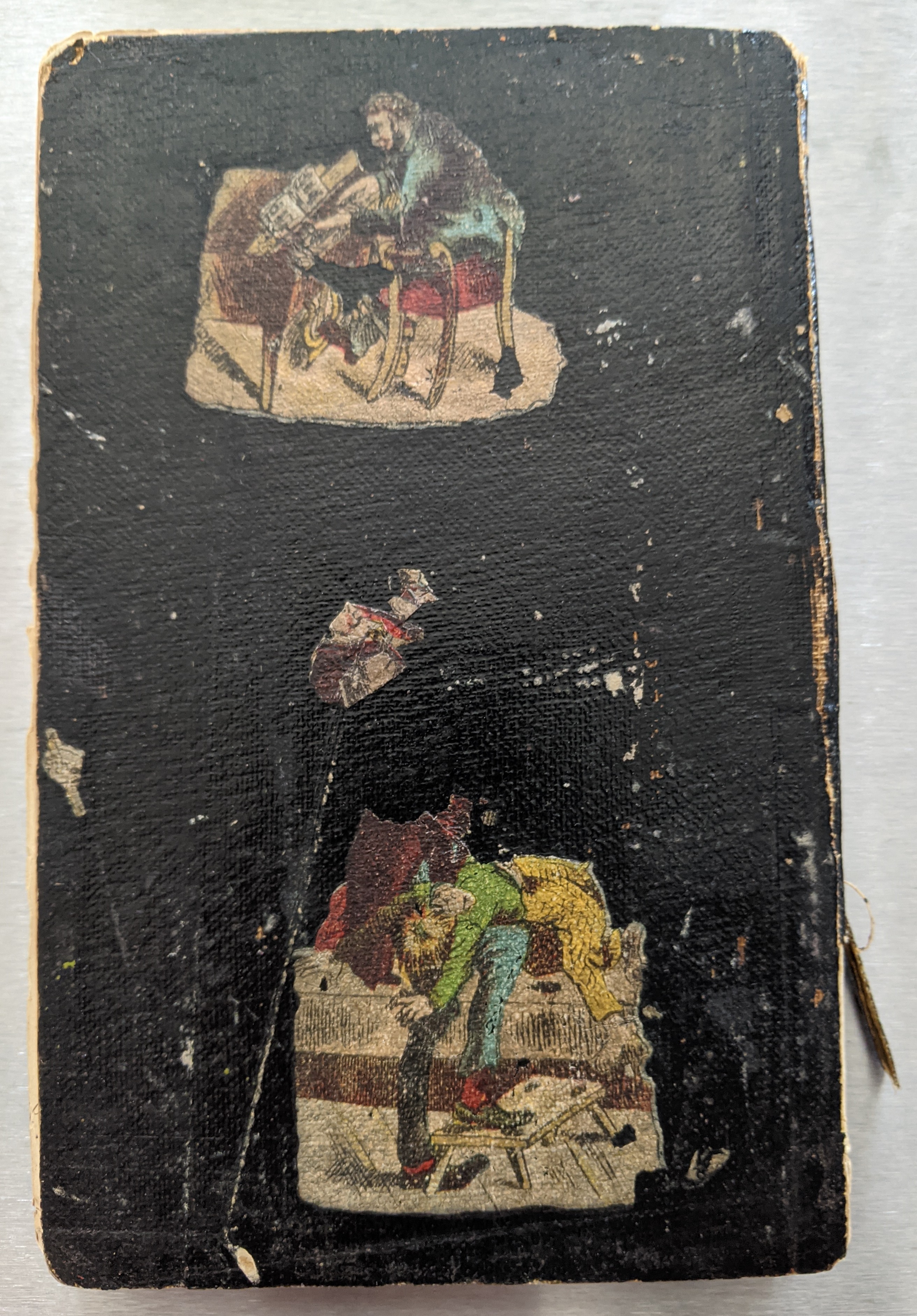

M 694 Margaret and Mary Gray diaries, 1883. Front cover.

M 694 Margaret and Mary Gray diaries, 1883. Recipes for puddings.

Over the next few days, the girls started getting their sea legs and the daily routine of rolling mattresses, dusting, and sweeping out their bunks began under the watch of the ship’s Matron, Mrs Simmons. They spent their evenings with dancing and singing, concluding with prayers before a curfew imposed by the Matron. The entries on entertainment and exercise offer an insight into how passengers amused themselves on long voyages, however Margaret’s descriptions of the onboard politicking are particularly illuminating, especially the escalating power struggle between Mrs Simmons and the Ship’s Surgeon-superintendent, Dr Marks.

Margaret was not an admirer: “I don’t like the Doctor, he speaks so gruff” (September 16th). She describes the doctor as a bully, given to bouts of heavy drinking. Margaret was not the only one who found him abrasive: she records on October 3rd that “the Doctor got a tumble last night, some of the sailors did for him in the dark and he was not able to get up this morning.” His treatment of passengers is rough: on one occasion he put two young men in handcuffs and left them on deck through a downpour, and on another threatened to report a seasick girl as a lunatic for refusing a command before chaining her to a bed in the infirmary, causing another patient to have a seizure from the commotion. The doctor seemed more interested in being in charge than in caring for his charges.

Matron’s watershed moment came on October 9th, when she ordered the girls to bed, only to be contradicted by Marks: “girls you do not need to go down unless you like.” In solidarity, the girls rose from their seats and declared “we are going down,” before dutifully filing out. Emboldened, Matron rose to the later challenges from Marks until he somewhat relented.

Margaret also recorded her personal thoughts throughout the voyage: she missed her parents, who they rarely saw; and was saddened by the deaths of infants on the voyage. The physical proximity onboard made the grief of their parents impossible to avoid, and the funerals of the babies distressed many passengers.

Margaret ended her diary on December 15th, one day short of their arrival in Brisbane, and therefore omits the voyage’s dramatic conclusion: quarantine at Peel Island until January 4th due to scarlatina, a bacterial infection which was highly dangerous before the use of antibiotics, followed by Matron’s laying an official complaint against Marks. Furthermore, the handling of the outbreak and quarantine breaches resulted in the ‘Berwick Law enquiry,’ held on the 23rd at the Immigration Board. Marks was called to explain his conduct to the board on both charges. While we have no record of Margaret’s response, I can’t help but imagine that she suppressed a little smile at the thought of the cruel Dr Marks being twice raked over the coals.

Marks was cleared of all wrongdoings due to lack of evidence – if only they’d had Margaret’s diary.

Dr Allison O'Sullivan

Related collection items from the John Oxley Library:

Other blogs by Dr Allison O'Sullivan:

Comments

Your email address will not be published.

We welcome relevant, respectful comments.