Cruising: Cross-Dressing at Sea

By Dr Marion Stell and Professor Celmara Pocock, 2025 Rainbow Research Fellows | 17 July 2025

This blog was written by 2025 Rainbow Research Fellows, Dr Marion Stell and Professor Celmara Pocock.

This is part of their research on the project: Queering the Lens: Cross-Dressing in Family Photograph Albums.

What a lark! Early-twentieth century sea voyages were long and passengers were inventive in creating their own entertainment. On many occasions passengers and travellers put on a costume for fancy dress parties. Men were free to dress as women – fairies and ballerinas were popular choices – women could borrow a sailor’s cap or uniform and enjoy an imaginary life at sea, and children could dress as popular characters of any gender. These activities were encouraged by the ship’s captain, and prizes were given for the best fancy dress.

Before the availability of commercial air travel, Queenslanders wishing to travel had to journey by sea. Ship voyages could be long, the popular route from England to Australia was one of the longest being 12,000 miles (nearly 20,000 km), or short cruises around neighbouring islands in the Pacific such as Fiji and New Zealand. Even after air travel became more common and affordable in the late 1940s, many people chose to take a cruise by sea as a holiday, enjoying the pace of life on the ocean and the freedom of social interactions and entertainment on board.

Crossing the Equator

Cross-dressing on board ships also has a longer history. Sea voyages from Europe to Queensland by immigrants and other travellers in the nineteenth century usually took upward of six long weeks by sailing ship. To reach Australia all travellers had to cross the Equator, an imaginary line at 0.0 degrees latitude, transitioning from the northern to the southern hemisphere. With this passage came a ritual performed by ‘King Neptune’, a practice with origins in a brutal and degrading initiation for sailors that later became a symbolic and fun rite of passage for travellers.

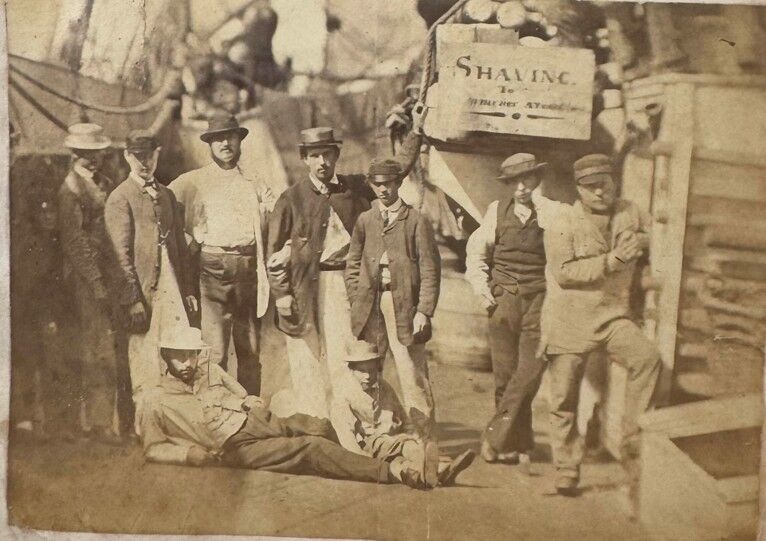

Parents Mary and John Nicholson and their daughter Frances left Wiltshire, England, sailing aboard the clipper Essex, and arrived in Queensland in August 1864. When they crossed the Equator the family witnessed a performance of this ritual: King Neptune accompanied by his ‘wife’ Salacia, both portrayed by male sailors, came over the bows, with other attendant sailors wearing masks and fancy clothes. According to tradition they lathered and shaved those who had not crossed the Equator before, then cleansed them by swinging them from the yard arm and dunking them three times in the sea. Neptune’s full beard and Salacia’s long hair were fashioned from ship’s rope.

Crossing the Line Ceremony aboard the Essex, 1864. APA59 Nicholson Family Photograph Album, John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland, Image 132844.

Shaving Ceremony aboard the Essex, 1864. APA59 Nicholson Family Photograph Album, John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland, Image 132845.

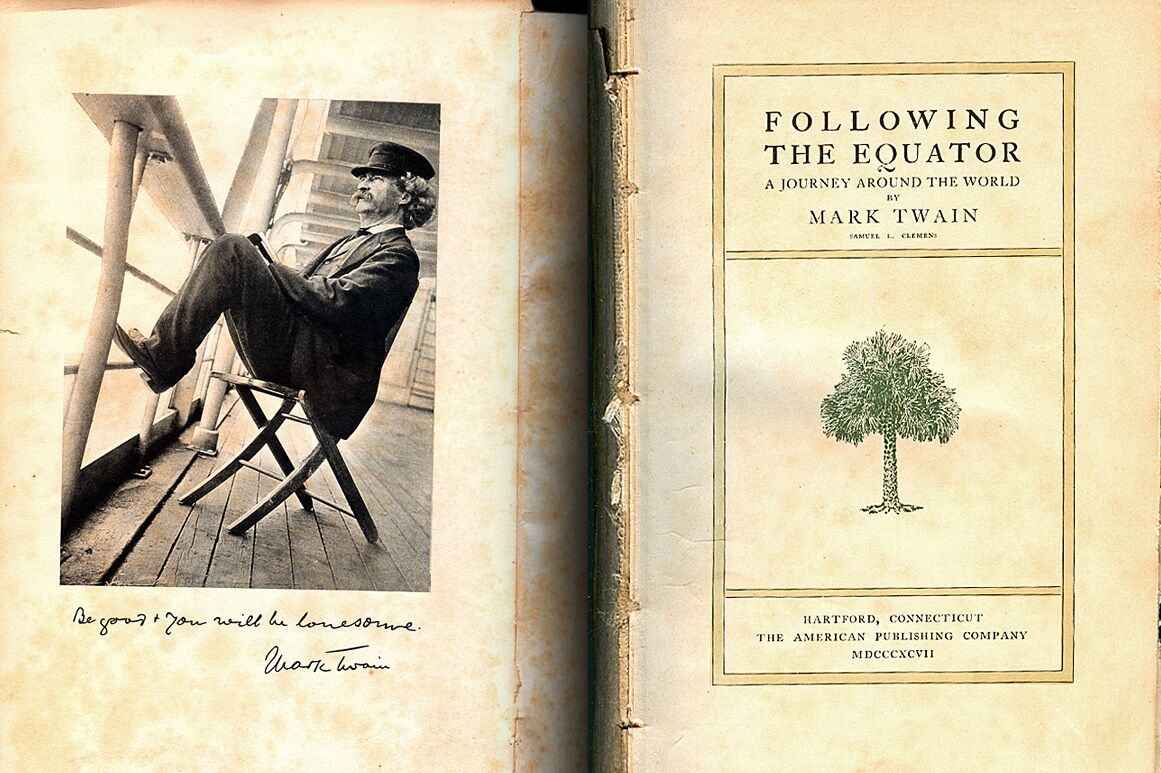

Forty years later American author Mark Twain described the ritual in his book, Following the Equator (1897). He wrote that the practice had largely been abandoned, ‘no fool ceremonies, no fantastics, no horseplay’, but that the keen anticipation of travellers when crossing the line remained. The Equator lay in a zone which experienced little wind, often referred to on a sea voyage as the ‘doldrums’, and Twain equated this with the monotony experienced on board and the travellers’ propensity to seek diversion in what he called ‘grotesqueries’. (1)

Twain, M. (1897) Following the Equator : a journey around the world / Mark Twain. Auckland, New Zealand: Floating Press. Read an online copy through State Library's catalogue or WikiSource.

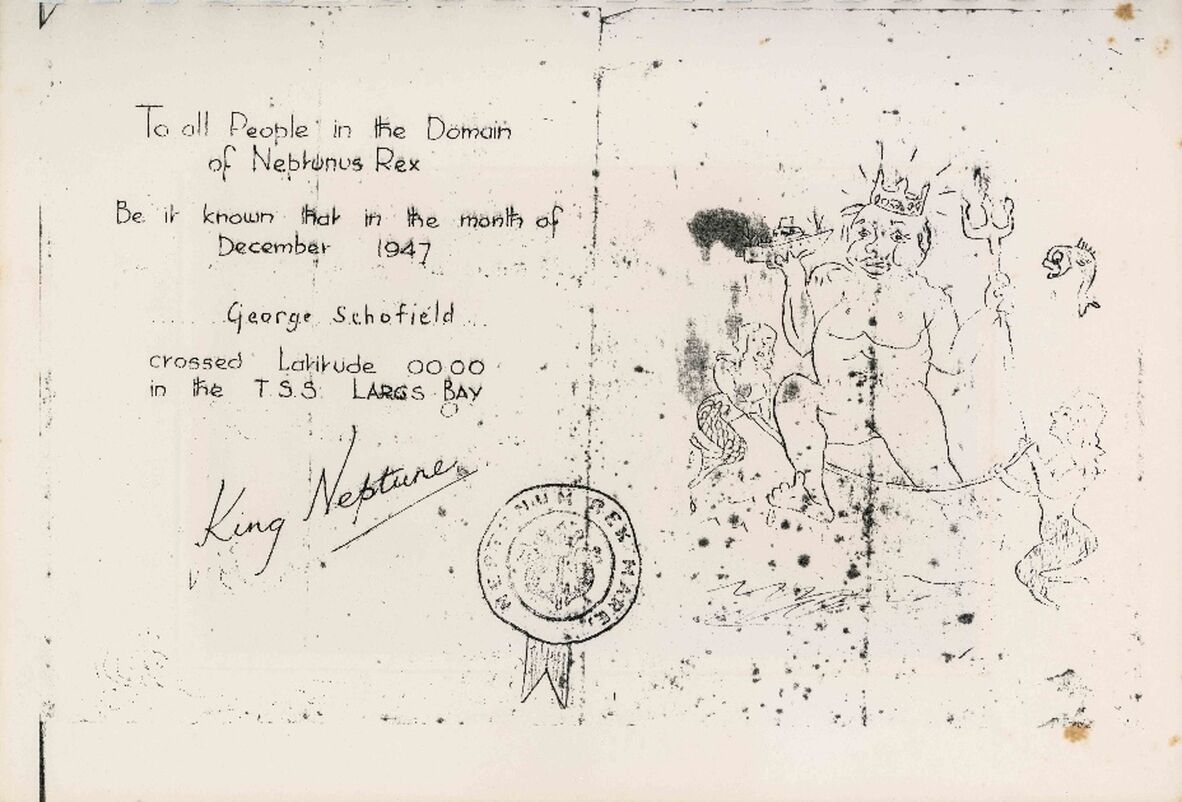

By the twentieth century, the practice was all but abandoned. The Schofield family migrated from Lancashire, England to Brisbane in 1947 aboard the one-class ship Largs Bay. Among 400 passengers were parents Harold and Mabel Schofield and their two children, a girl and a boy, Gavine aged 4 and Michael (George) aged 11. Harold noted that the ceremony of crossing the line had been dropped ‘because it involved a great deal of horseplay and someone was nearly always hurt’. But he bemoaned its absence, ‘it would be pleasant to be able to say that you had ‘crossed the line’ with all the old pomp.’ Children on board, however, were warned that they would ‘feel a bump’, and they did, caused when ‘a playful seaman had dropped a large spanner at the exact moment.’ Each child received a certificate to commemorate the occasion, decorated with a picture of King Neptune, mermaids and fishes. (2)

Neptune’s Certificate, 1947. 31911, Schofield Family Photographs and Correspondence, John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland.

While the crossing the line rituals had been changed, cross-dressing remained a popular pastime on board. Diversionary activities were keenly sought out by generations of sea travellers and cross-dressing and fancy dress were easily created with material resources at hand. Aboard the Largs Bay adult and children’s fancy dress contests were held, with crepe paper, cardboard and silver paper sought out for children’s costumes. Harold noted that before the adult fancy dress the ship’s carpenter shop was ‘full of people contriving all sorts of things out of canvas, bits of wire, and pieces of wood’. (3) Corks supplied by the barman were burnt and used for face blackening, while cocoa and custard powder from the kitchen were similarly used for ‘black’ or ‘yellow’ face. This practice of imitating other races in fancy dress, although accepted by many at the time, drew on offensive racial stereotypes and was belatedly abandoned. Men cross-dressing as women similarly drew on negative stereotypes but also included a sense of freedom to be the other sex.

Cruising the Pacific

While short-term cruises did not involve any crossing the equator ceremonies, they remained occasions for fun and frivolity on board centred around a night of fancy dress. Here again cross-dressing was a popular option for those on board.

Joyce Ann Tuesley took a cruise to New Zealand and Fiji aboard the SS Oronsay, in 1955. For a fancy dress contest on board, rather than making a costume she simply borrowed items more commonly worn by men, namely a sailor’s hat and shirt. She paraded before the other passengers and the camera with some degree of shyness or embarrassment.

34142 Tuesley Family Photographs, John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland.

A group of six men on the same cruise went to more trouble to create costumes that allowed them to cross-dress as fairies or ballerinas. They wore makeshift dresses tied at the waist and held up by one shoulder strap, adorned with pieces of bright silver paper, carried small star wands, and wore silver paper tiara-style head bands. Two of the party wore bright red lipstick and make-up. Their poses for the camera exuded a confidence and a cheekiness indicating that they enjoyed the joke and fun of cross-dressing immensely.

34142 Tuesley Family Photographs, John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland.

Both Joyce and the group of men were presented with prizes by the captain of the SS Oronsay, although Joyce Ann Tuesley still appears self-conscious about the attention brought by donning the uniform of one of the captain’s sailors.

34142 Tuesley Family Photographs, John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland.

Sometimes the inversions of race and gender combined in a single fancy-dress outfit. John Duryea took a cruise in 1948 to the Pacific Islands onboard the RMS Orcades. (4) He was photographed on the ship’s fancy dress night in an elaborate and carefully crafted costume. He appeared not only as half man/half woman, but as half black/half white. The use of ‘blackface’ makes it inappropriate to reproduce the photograph here, but the extraordinary image is worthy of description. The photograph shows John’s left side dressed as a white man in check shirt and trouser leg. His left side is dressed as a black woman. His portrayal of another race appears to be achieved by applying shoe polish to his face, arm, hand and leg. The female gender is represented by items of women’s clothing – a shirt and skirt, the latter patterned and possibly a colourful sarong, with a bracelet around his ankle. The whole ensemble is held together with a belt. He gives the photographer a wave and looks deadpan into the camera, while other passengers in fancy dress surround him.

Cruises and other journeys by sea provided a space away from home for the practice of dress-ups and cross-dressing for adults and children. Drawing from ancient on-board rituals of King Neptune and his wife Salacia, fancy dress occasions provided opportunities for diversion and fun on pleasure cruises and long transit voyages. Making use of whatever was to hand, passengers swapped clothing, accessories, and make-up, and adopted exaggerated body stances in posing for the photographer, to accentuate the act of cross-dressing.

Finding these Photographs

This research is part of the project Queering the Lens: Cross-Dressing in Family Photograph Albums. These images represent just a handful of the many new images of cross-dressing this project has uncovered in the family photograph albums of the State Library of Queensland. In coming months we will aggregate and interpret these images thematically and publish them in future blogs. If you have photographs of cross-dressing at sea, or any other relevant cross-dressing images please contact us at the library on qldmemory@slq.qld.gov.au.

Dr Marion Stell and Professor Celmara Pocock, 2025 Rainbow Research Fellows, State Library of Queensland

Read other blogs by Marion and Celmara

- Queering the Lens: Cross-Dressing in Family Photograph Albums

- Queer Eye: How to Identify Cross-Dressing in Family Photograph Albums

Read more blogs about Queensland's LGBTIQA+ history from previous Rainbow Research Fellows.

The 2025 Rainbow Research Fellowship is generously supported by the Queensland Library Foundation.

References

- Mark Twain, Following the Equator: A Journey Around the World, The Floating Press, 2018 (1897). ProQuest Ebook Central, http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/slq/detail.action?docID=432373.

- Interestingly, America scholar Susan Harris writes that Mark Twain himself dressed in women’s clothes, taking part in family theatrical performances in 1890, and she points to the number of men and women who cross-dress in Twain’s fiction, see Susan Harris, Mark Twain, the World, and Me: Following the Equator, Then and Now, University of Alabama Press, 2020.

- Letter by Harold Schofield, 7 December 1947, Schofield Family Photographs and Correspondence, Acc 31911, John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland

- Letter by Harold Schofield, 10 December 1947, Schofield Family Photographs and Correspondence, Acc 31911, John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland

- Duryea Family Photographs Acc 29587 O/S, John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland

Dr Marion Stell and Professor Celmara Pocock were awarded the 2025 Rainbow Research Fellowship for their project, Queering the Lens: Cross-Dressing in Family Photograph Albums.

Comments

Your email address will not be published.

We welcome relevant, respectful comments.