A childcare centre closes in the Valley: A history of "Practical Sympathy"

By JOL Admin | 6 December 2011

The childcare centre that my children attend, in Brisbane’s Fortitude Valley, is about to close down. Bear with me. As a parent this of course resonates with the sound of children’s activities, with the voices of teachers, with exuberant greetings and cries of despair at a broken toy or the wrong t-shirt – but what does it mean from a historian’s perspective. Well, a lot, actually, and here’s why.

This centre is part of the “C&K” chain. As a Sydneysider, this acronym was new to me when I arrived six years ago, from a state where the word “crèche” isn’t used. But the Crèche and Kindergarten Association is a presence across the whole of Queensland. The organisation’s story has its origins in the state’s management of social welfare, of poverty, and to a whole raft of radical reformers and visionaries. But this is not a tenuous link to one site amongst many – the organisation itself began in the Valley within spitting distance of the building whose doors close next week (not that we spit, do we, children, we use our words et cetera).

I found parts of that story, going back to 1907, here in the John Oxley Library.

The Valley was always a “mixed” place. It was known as one of the poorest areas in Brisbane, but it was also home to the middle classes. It had industry, retail, shipping and working girls; it had religious institutions and social reformers; it had “street boys” and street sweepers; and it had an increasing number of citizens who wondered what might change, what needed to change.

In 1907, too, more and more working class women were doing paid work; just as a number of middle class women were extending their own skills and political concerns outside the home. Of course, there were activist working women too. But a group of reformers who lived in and around “Poverty Valley” were concerned with the life of the street; were worried about how these women would look after their children; and believed in intervention and in the role of reform through both activity and edification. And there, on the corner of Brunswick and Ivory Streets – where there’s now a collection of nightclubs, host to occasional headline-making behaviour – was a tobacco factory that had just closed down. The smell of tobacco had gone, but so had a significant number of jobs.

One of the leaders of this group of change-artists, was an American-born Congregationist minister with the unlikely name of Loyal Wirt. Wirt, and some of his cronies – both women and men, in a period when these stories tended to be hung on the hook of one male leader – decided they wanted to do something. Together, they formed the Brisbane Institute of Social Service, and they wanted a place to act as an antidote to the mean streets. A site for a boys club, a girls club, a crèche and a kindergarten, at the very least. So they approached the owners of the now-closed tobacco factory, and asked if they could rent the space. To their surprise, they were given the space for free, for a while at least, and off they went.

This is the lineage, for that childcare centre, where 104 years later I send my children.

Some things have changed. Childcare is no longer a question of social welfare for the working class, and a space for “saviour”, although the tradition of “teaching” parenting as a way to save the nation and build citizens (etc) hasn’t entirely gone away. The childcare centre is no longer in an old tobacco factory, but the tradition of moving every few years, fighting over rents and ownership, and dissent about the philosophy behind such centres has a fine long history of acrimony. There is no longer a boys club with a billiards room and hopes to build Australia’s first navy from its cadets. (It’s 1907 – there was no navy. The so-called “Great White Fleet” from the US was due to visit Australia, the following year, and excite the country both with its seafaring spectacle and with the idea of two White nations in the Pacific. Nationalism was simmering away. But enough of that.)

Because the tradition of social reform is a rich and interesting one. It’s at least as dynamic as the better-known stories of nationalism and alliances. So when a childcare centre closes in one community, there’s more to be salvaged than artwork to stick on your fridge.

Not only that, striking and familiar figures from Brisbane’s history keep coming up as part of the story. The first woman doctor in Brisbane, Lilian Cooper, and her life partner Josephine Bedford, were mainstays of this and other reform movements. Those who wanted to change the lives of the working class in Fortitude Valley also wanted to build parks and playgrounds, to teach mothercraft, to reform government, and to change women’s lives and ability to speak on a world stage. Indeed, these reformers were part of the emerging international rights movements that saw ideas transformed from the US and Europe and elsewhere.

Some more details, then. There are two histories of the C&K system, including a commissioned history by the inimitable Brisbane historian Helen Gregory (Playing for Keeps: C&K’s First Century), and a more in-house version by C&K “insiders” Peggy Banff and Norma Ross (The Peppercorn Trail”: The story of the Creche & Kindergarten Association and its People). Helen Gregory’s history places the movement in its wider context, from Brisbane specifically through modernity and international reform movements, the role of the state and changing educational contexts, right up to the present. The Peppercorn Trail does something similar, but has much more detail about the administrative details of the organisation. Both draw upon the C&K’s own archives as well as oral histories. I’m not going to replicate their work – as it does something I can’t do in a blog entry. Instead, I want to tell a few stories (focusing on the very early years) and draw some broad connections, especially in the context of the State Library’s own collection, and the other histories that emerge from the archives.

In part, though, it’s a reminder that “childcare” – which in 2011 is so much part of the fabric of everyday life that we don’t necessarily think about it – has its own history. Or rather, it has many histories. A radical history, of reform. A conservative history, of gender and control. An educational history, of institutions and regulation. A history of work, opportunity, and care; of wages, buildings, and change. And many many personal stories and memories.

Back, then, to 1906. The very first minutes of the first Committee Meeting of the Brisbane Institute of Social Service (Papers of the Brisbane Institution of Social Services, JOL OM72-21/1B . Minutes, OM72-21/3), on 20th March, was chaired by the Rev. Loyal Wirt.

“The Chairman thought the first move ought to be the establishment of a crèche on the ground floor and thought the matter would be taken up by the ladies of the several churches. Mr Wassell kindly offered to equip one cot for the crèche or make one of 20 at ₤5 to cover the first outlay of ₤100.”

By the meeting just two weeks later, it was decided that the crèche should operate at nominal cost to mothers – say, 2d a day.

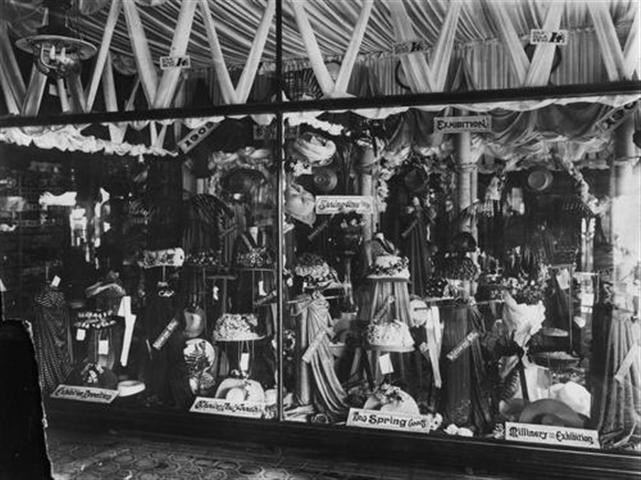

By the time of the second Annual Report – for 1908/09 – there was not only a crèche and kindergarten, but also a boys’ club, with boxing, billiards, and a “temperance bar” , while the Girls’ Club included a swimming club as well. " href="/blog/jol/files/2011/12/creche-small.jpeg" title="Creche at the Brisbane Institute of Social Service, 1907. State Library of Queensland, negative number 36636">

“Practical Sympathy” – not yet called charity or donations, it used familiar techniques of combining heartfelt stories with claims for the greater good, to bald-faced requests for equipment (for a free piano and an old billiard table, for example). Time and again, they proclaim their origins:

“the Institute came into existence, bearing with it noble aspirations, laudable objects and practical aims for the poorer classes of the City.” (Letter to Mr B Whitehouse, businessman, 18 Dec 1907, p 21 of letterbook)

And extend their claims outwards, to the nation:

“a great national asset is being conserved and proved in the persons of babies being cared for in our Day Nurseries while the mothers are out at work; and the little children whose minds are being trained in our Kindergarten department” (letter to Mr Maxwell, Bundaberg, 20 Jan 1908, p 71 of letterbook)

(And by 1930, when the Institute was busily documenting its own history, it described itself as an organisation founded to "help towards the social uplift of the then residents of Brisbane."

And then back again into the homes and lives of the working class women who children attend the crèche.

“I could tell you many pitiful stories of poor women whose lives are made weary by the dragging of little fingers at their skirts and of the little folks themselves who now receive their education in life from the gutters or are locked up at home while Mother is seeking bread for them . . . We want to bring them into our big loving home, feed, clothe and teach the little ones, and inspire the young men and women with hope and give them through the Institute windows and influence a better and truer outlook upon life.” (Generic letter to plea for donations, 15 Sept 1908, p 356 of letterbook)

Not to mention the work of cleaning up the street, because “you are doubtless aware that here in the valley there are crowds of young men who apparently are aimless, and walk about the street with seemingly no object in view” (letter to Mr Harris, Clarence Hotel, 3 Jan 1907).

And then, in between the appeals for practical sympathy, are details about who will scrub the lavatory outside the crèche door once a week . . . and hints of the cracks that are beginning to appear behind the righteous aims. Stories of rumours and ructions, hints at disquiet, elliptical references to arguments that are going on.

Again, the formal histories are able to make more sense of this . . .

Because by 1911, the Creche and Kindergarten split from the Institute, and went its own separate way.

From here, the larger story of social reform gets messier, but the intersecting organisations, and the cast of characters, remains vibrant. While the “street larrikin” required bringing inside, by an avowedly non-religious organisation, to be made into a “creditable citizen”, there were also moves afoot to change the streets themselves. The origins of the international “city beautiful” and “parks and playgrounds” movements were in this period, and the ideas travelled the world. Charters for the rights of women and children were being drafted, in Brisbane, Sydney, New York and elsewhere. Action moved from “practical sympathy” to practical action, by organisations like the National Council of Women (see for example, History of the National Council of Women in Qld, the First Fifty Years, 1956. JOL J305.4/FIR/C1), and the Playground and Recreation of Association of Queensland, whose aims – and people – overlapped with that of the Creche and Kindergarten Association. Central to many of these organisations was the extraordinary figure of Josephine Bedford, who seems to leap from the most mundane of administrative papers, with her energy and interest and sheer involvement in things.

(I first came across Jean Bedford in an exhibition on love and travel held at the State Library of Queensland (Travelling for Love) but she appears in collection after collection. Clearly a force to be reckoned with, to use a cliché.)

And by 1911, and this split with the original Social Institute structure, the childcare centre in the Valley had already had to move to new premises. The draper James McWhirter offered up an empty shop to use as a baby’s nursery from 1910, and the year after there was another move. In the same year, C&K opened a Kindergarten Teachers College, and began to have links with both government and researchers.

World Wars, centre closures, workers in munitions factories, polio and influenza epidemics, lead poisoning from toys, theories about play, arguments about women’s lives and relationship between home and work, agonising about what and how to feed children, the role of fathers . . . all of these are tied up with the story too. All these can be found within the archival record – where the papers hold whiffs of “convalescent food” and egg custard, powdered paint and rooms full of children, within even the driest administrative record.

Which takes me back to where I began, as a working woman, with a partner and two children, and a C&K childcare centre in Fortitude Valley, that’s about to close: 1907 to 2011.

Kate Evans, Historian in Residence, John Oxley Library

Note The most obvious papers have been listed in the text (above) or referenced via hyperlink. Other papers accessed for this story, which deserve a more detailed study (and more blog entries to come), include:

- Lady Phyllis Cilento, Square Meals for the Family, Mothercraft Association of Qld, Qld Social Services League, 193_?. JOL P641.5/cil

- Brisbane Kindergarten Teachers' College: Diamond Jubilee Souvenir 60 years, 1911-1971, Creche & Kindergarten Association of Qld, Brisbane, 1972 (JOL P372.218/cre)

Comments

Your email address will not be published.

We welcome relevant, respectful comments.