The challenge of a Brisbane ‘model suburb’ in Newmarket 1933-1935

By Stephanie Ryan, Research Librarian, Information Services | 19 November 2020

Backyards in Newmarket, August 1953. Brisbane City Council Archives.

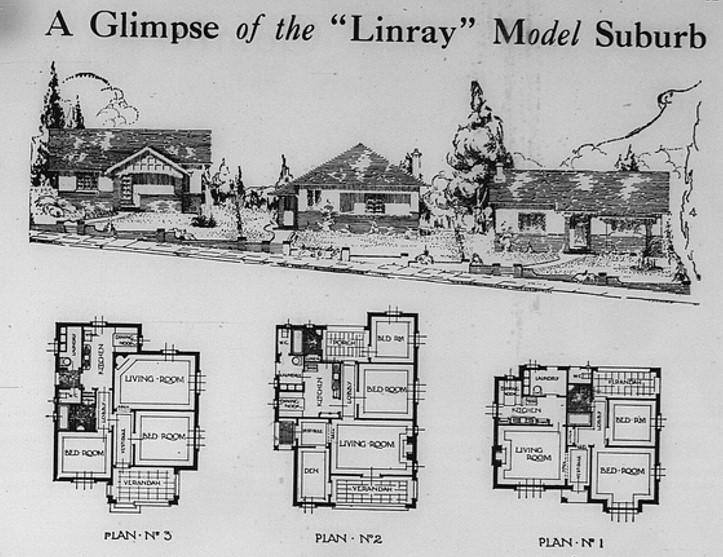

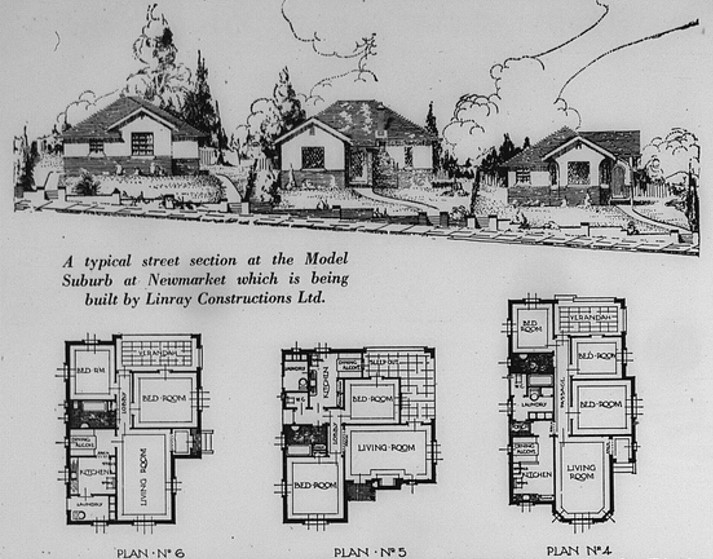

Newmarket, during hard times, had some shabby, repetitious timber and tin housing with backyard toilets. Linray proposed something else for which they employed Arthur W F Bligh. He was a Toowoomba-based architect who had been writing regularly for the Toowoomba Chronicle in a series of 39 columns July 1931-December 1932: ‘Homes to meet modern times, economical buildings of attractive design’ and another series with the theme of modern architecture. Each column featured a sketch of a house, a floor plan, and a cost. Bligh believed that the wooden Queenslander was not economical of upkeep, long-lasting in value or adequately interesting.

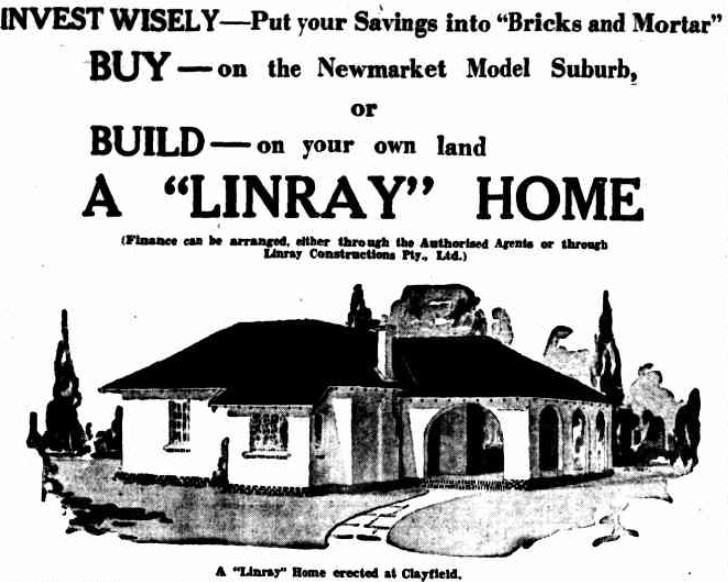

He was going to create housing that was individualised but harmonised, utilitarian and economically priced at £800-£1250 per home. He believed an attractive, well-proportioned home suited to the climate and the needs of its residents could be built economically. It did not need to be large. He favoured space-savers such as built-in cupboards, set-in baths and basins in a general Mediterranean style. He was keen to use stucco, tiles and textured surfaces with minimal ornamentation. For Linray he provided additional styles: Colonial, Simplified Colonial (variations on European and American styles), Colonialised Old English, Old English, Spanish Mission and Cubistic (flat-roofed porch). Terraced gardens, brick garden walls, a children’s playground, even 2-3 tennis courts were planned for this model suburb. (See sketches below).

The steering wheel and society & home, 1 February 1934, p 31.

Linray asked the Council to supply intermittent relief labour for building fully bituminised roads, water channelling, footpaths and sewerage connection. The Council agreed, with some conditions: it asked that the company deposit £1,500 towards the estimated cost of £5,906, and lodge £1,500 as a guarantee that 45 houses would be erected within two years.

In order to appreciate how innovative this was, it needs to be remembered that features of the proposed developments would not reach much of Brisbane for decades. Clem Jones developed a town plan, sealed the roads and sewered Brisbane extensively and completely during the 1960s. As the Brisbane City Council detail plans (1930s-1950s) reveal, many of the suburban streets had bitumen in the centre only. The shoulders of the roads were gravel and made homes dusty. Linray’s planned greenery and gardens would beautify the area.

The steering wheel and society & home, 1 February 1934, p 30.

The first five houses were built on Newmarket Road. By January 1934, 20 homes were completed. Subsequent houses were built in Lind and Gray Streets. Overells, a major Brisbane department store, decorated a sample home at their own expense and worked in conjunction with Linray to assist buyers with quality furnishings suited to their personal taste. The Lord Mayor praised the project. All the Brisbane newspapers ran generous, illustrated articles on the ‘model suburb.’ Advertising was diverse and lavish and Linray was prepared to build in other suburbs.

Advertisement for Linray homes. Courier Mail, 24 January 1934, p 20.

Journalist Geoffrey Luck relates in ‘History’s Home Truths About Making Owners of Renters’ in Quadrant 11 May 2019 that his father took up this offer. He had a block of land at Camp Hill on which he had a Linray design built. Geoffrey Luck considered that his father, on a PMG technician’s modest wage, made a wise decision to get a quality home. The family lived simply, and the loan was repaid in 19 rather than 30 years. In 2013 he took a series of photographs of the Newmarket Linray homes, but also included his family’s Camp Hill house, now available on Trove from the University of Queensland.

Despite general enthusiasm, not enough people were buying. By February 1934, 20% price reductions were offered. Land on which Linrary had not built, over 16 acres, was auctioned in June 1934 but there were no offers. Linray had to cede titles to Brittains who supplied the bricks. In September 1935, the Council put into operation the penalty clauses attendant on Linray meeting its obligations to it.

The homes over time: 1930s-present

State Library has some photos of Linray homes in Lind and Gray Streets taken in the late 1960s-early 1970s. Frank Corley took them as part of a business, photographing homes in south-east Queensland to sell the cardboard-framed pictures to owners. Those he did not sell he kept to avoid paying sales tax on them. It is possible to compare some of the 1930s’ houses to the Corley photos and Geoffrey Luck’s 2013 pictures.

21 Gray Street, Newmarket, late 1960s-early 1970s. Frank Corley, State Library of Queensland.

21 Gray Street, Newmarket, 2013. Geoffrey Luck, University of Queensland.

Did the Linray homes live up to their promise?

‘This is the first attempt of note, in Queensland, outside Workers' Dwellings, to remedy the state of things introduced by the depression’ Daily Standard 4 August 1933, p5. The project also provided relief work for unemployed workers. It recognised that more modest earners were entitled to quality homes, aesthetically pleasing, utilitarian and economically produced in an attractive suburban setting. It raised the awareness of the Brisbane public to innovative housing ideas, which would not be common until a few decades later. Have the homes stood the test of time? Look at Geoffrey Luck’s photos on Trove to see the homes in 2013.

Find out more

- Explore the Trove options for newspapers or images to search for pictures of Queensland homes from a variety of sources including Corley.

- Read Arthur W F Bligh’s illustrated articles

More information

Family History Research Guides - https://www.slq.qld.gov.au/research-collections/family-history/family-history-research-guides

One Search - http://onesearch.slq.qld.gov.au

Comments

Your email address will not be published.

We welcome relevant, respectful comments.