Anzac Cottage No.1: Lost in the Woods

By Don Watson - John Oxley Library Fellow 2012 | 30 May 2013

Anzac Cottages were built in Queensland as a community response to the appalling casualties on the Western Front during World War 1. They were made available at low rent to disabled servicemen or more often their widows and children, provided that the widow was of ‘good character, remained unmarried, be not seen drinking in public or having gentlemen callers’. At least 54 cottages were erected on donated sites by volunteer labour using donated materials. Their construction became community events with stump capping and hand-over ceremonies by civic dignitaries, accompanied by parades and brass bands. Cottages were given patriotic names such as Strathearn, at Alderley, which was the 37th of 38 Anzac cottages to be built in Brisbane. Strathearn was completed in July 1920 and occupied by the family of John Warner, who had recently died from injuries he sustained at Ypres in 1917. It was owned by the same family until 1998, when John’s daughter Florence died. She too, was a war-widow, but due to World War 2. Strathearn is listed on the Queensland Heritage Register.

Who designed the Anzac Cottages?

The Heritage Council’s citation for Strathearn (Place ID 602064) comprehensively explains this community initiative, but my research of Anzac Cottage No.1 had a particular bias. As John Oxley Library Fellow for 2012-13 working on A Biographical Dictionary of Queensland architects 1900-1950, I was seeking the names of the designers of the cottages. Not everyone is as interested as I am in the role played by architects, but what I found was initially more perplexing.

Where was Anzac Cottage No.1 located?

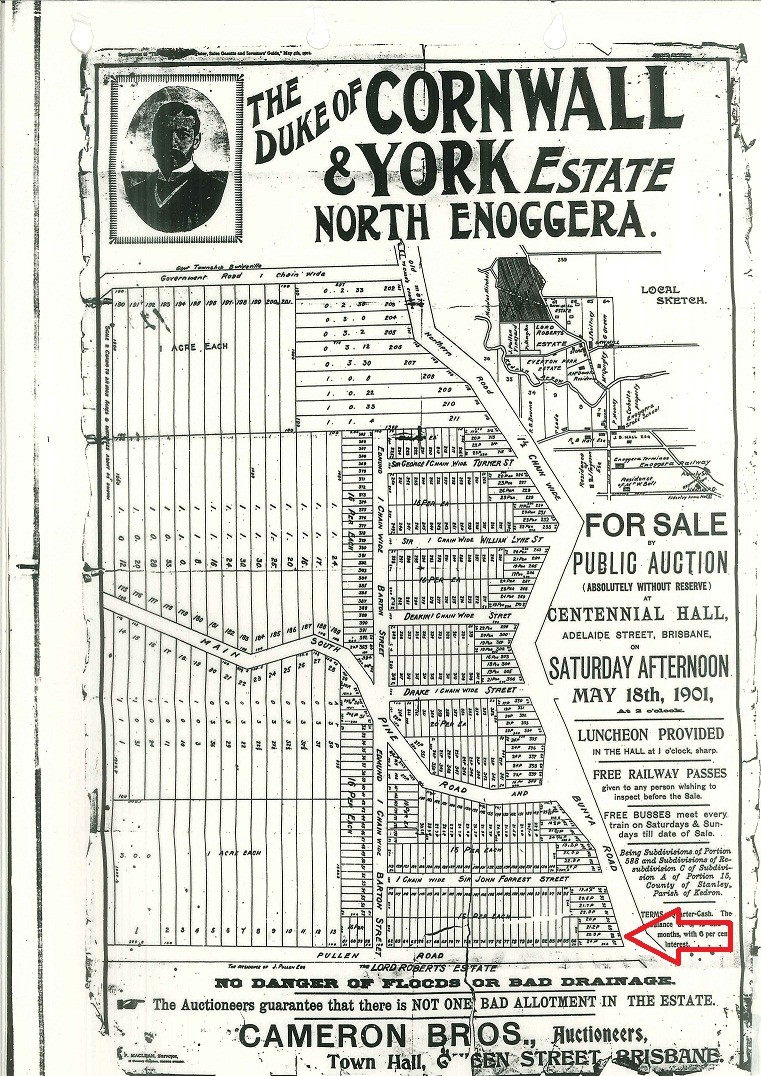

Cottage No.1 was built on land donated by Mary Jane Bentley, a widow since the death of her husband George Bentley in 1911. The land was part of the Duke of Cornwall and York Estate at North Enoggera, subdivided when the Duke (later King George V) visited Australia to open the first Federal Parliament in 1901. He’d been to Brisbane before in 1881, as Prince George and at that time, third in the line of succession. The Duke used the title Duke of Cornwall and York following the deaths of his elder brother in 1892 and Queen Victoria in January 1901, which made him next in line for the throne after his father, King Edward VII. Continual repetition of his title during the 1901 visit was good publicity for the Estate which was auctioned in May 1901. Despite the site of Anzac Cottage No.1 being prominently located closest to the city centre, subdivisions 87 and 88, comprising 1 rood 6.3 perches on the corner of Pullen and South Pine Roads, did not sell to George Bentley until 1904. It remained undeveloped when he died in 1911 and was still vacant when the land was donated in 1917 by his widow for construction of an Anzac Cottage.

Duke of Cornwall & York Estate Map, 1901. John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland

How was Anzac Cottage No.1 built?

The Queensland Railways Department offered to provide plans for the first cottage, but its construction by volunteer labour using donated materials was simplified when a prefabricated dwelling was offered by the Brisbane sawmiller and timber merchant, Brown & Broad. Brown & Broad had launched their Newstead ‘ready-to-erect’ Homes in 1915, in competition to James Campbell & Sons’ ‘redi-cut’ houses which were already well established. Breakfast Creek Rd at Newstead was the location of the firm’s workshop. The First World War was an inopportune time during which to market their product and by 1917 Brown & Broad probably welcomed an opportunity to promote their houses. They also made available one of their foremen, EJ Chilton, to supervise its erection. Chilton later left Brown & Broad to establish his own company The Austral (Ready-to-Erect) Housebuilding Co. which provided material for some of the later cottages.

Cover from "B & B" Newstead homes : a catalogue of "Ready-to-erect" homes. John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland

When was Anzac Cottage No.1 built?

By mid June, 1917 Jack Munro, manager of the Brisbane Stadium, had made considerable progress with an idea to erect cottages for ‘returned heroes’ and sought volunteers to assist with their erection. By the end of the month a site and materials had been donated, unions had agreed to provide labour, the stumps capped, and ₤10 worth of fowls promised for the first occupant. Motor trucks were lent to convey volunteers to the site and food donated for various ladies including Mrs Bentley, donor of the land, to prepare lunches for the workmen. Work on the superstructure commenced on Sunday 15th July. With 47 tradesmen including several boxers from the stadium as labourers, the cottage was half completed by the end of the day. It was publicised that progress the following Sunday would be recorded on film, attracting up to 300 spectators who would be entertained also by a brass band. When work finished, all that remained to be done was the fitting of some joinery and painting which were carried out on July 29th leaving only finishing touches for August 5th. On August 12th, in front of 1500 onlookers and a cameraman, the Queensland Governor handed the key of the cottage to Mrs Woods, a widow with five children. Exhibition of the film, as support for a main feature at local picture theatres, was intended to raise money towards future cottages. It was announced that henceforth that Anzac Cottage No.1 would be known as Kitchener’s Cottage after Field Marshall Kitchener, who had drowned in June 1916 when HMS Hampshire sank after hitting a mine.

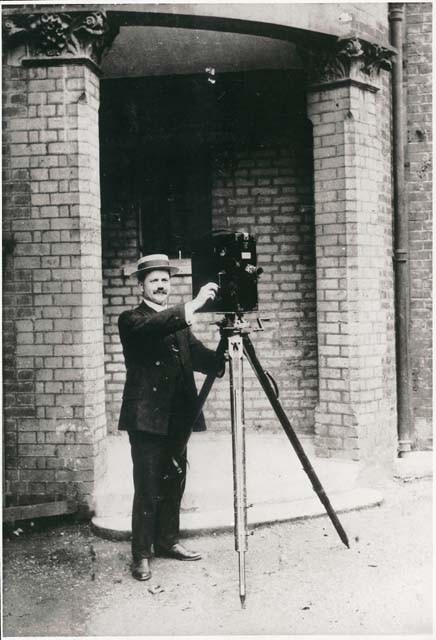

Who filmed construction of Kitchener’s Cottage?

In what were early days of film-making, who was the cinematographer? The film which was shown at Jack Munro’s Stadium (then used as a picture theatre as well as for boxing) can’t be found, but given the chemical composition of early film, it almost certainly doesn’t survive. But the papers of the Queensland War Council held by the Queensland State Archives include a record of the hire of a car to take a ‘Mr Cook’ to Enoggera. Mr Cook proved to be Sidney Cook, a pioneering Australian cinematographer and Brisbane cinema proprietor. A descendent made available photographs of Sidney Cook but had no knowledge of the film about Anzac Cottage No.1. The film would have resolved what the cottage was like.

World War I Peace Procession in Brunswick Street, Fortitude Valley, Brisbane, Queensland, ca. 1916. showing Cook's Picture Palace. John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland. Neg 165688

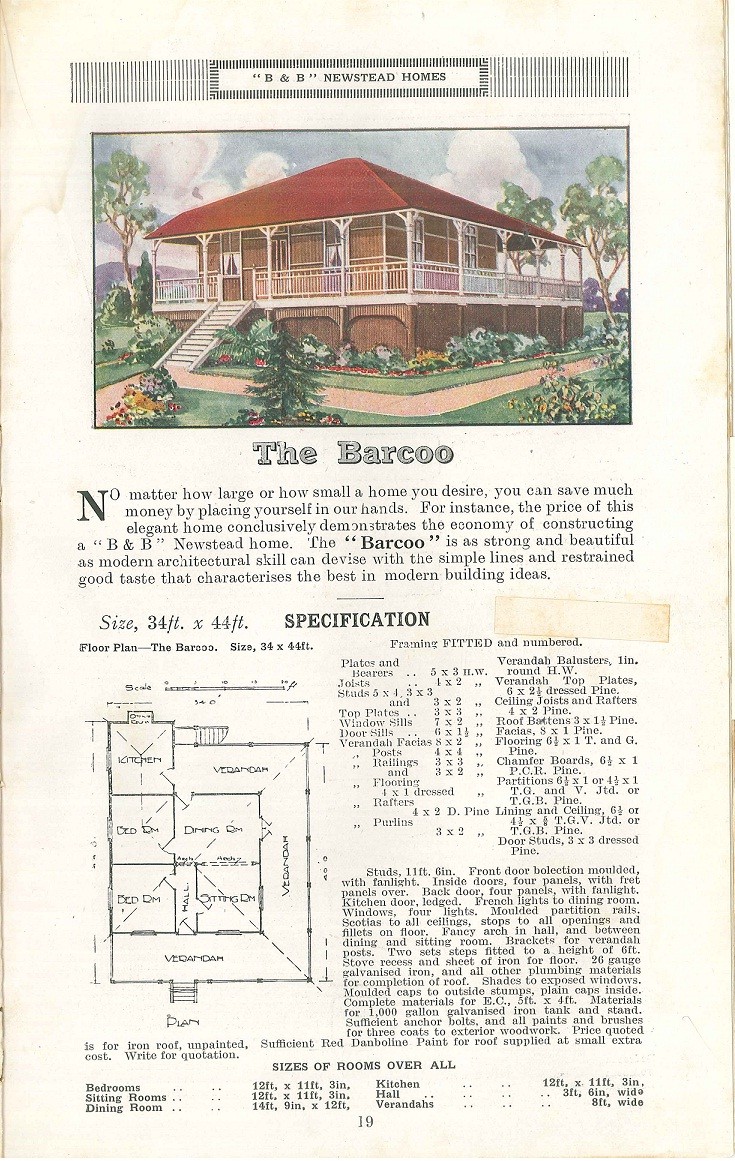

Which of the many Newstead Homes was Kitchener’s Cottage?

The cottage has been demolished and no photograph has been found in the Library’s collection. A drainage design drawing held by the Brisbane City Council (Plan 2516) shows an outline of the cottage. Brown & Broad issued catalogues of their Newstead Homes, of which the library has two copies dated 1919. Each house type was named, but the unlike the patriotic names given to Anzac Cottages, the Newstead Ready-to-Erect homes were given Queensland place-names. Based on the outline of the donated Anzac Cottage No.1, the most likely design was a Barcoo but with the side verandah omitted. That sort of modification was part of the service which Brown & Broad offered and is understandable in the circumstances.

Plan for the Barcoo from "B & B" Newstead homes : a catalogue of "Ready-to-erect" homes, John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland

Who was the architect?

Brown & Broad employed their own architects who included in 1917 the English born and trained Victor Denham (1889-1964). Also on the staff in 1917, was Robert Percy Cummings (1900-1989), later, first Professor of Architecture at the University of Queensland. Cummings’ mother, Catherine Elizabeth Brown may have been related to George Brown of Brown & Broad, but any relationship is yet to be established. None of the individual designs is attributed to particular architects, of whom there may have been others in the office between 1915 and 1917.

Who owned Kitchener’s Cottage?

An investigation of the Anzac Cottages, conducted in 1930 by the Public Curator who by then was responsible for the Cottages, found that often the ownership of donated sites had not been transferred, and that land titles remained in the donors’ names. Initially the cottages were rented by the Anzac Cottages sub-committee of the Queensland War Council, and in 1917 it may have been unresolved who the owner ought to be. Following the Public Curator’s investigation, it was claimed that these oversights were rectified. Although Cottage No. 1 is mentioned in the 1930 report, the land remained in Mary Jane Bentley’s name, even after her death in 1946. It was only rectified for the site to be sold in 1967.

Who was the first occupant of Kitchener’s Cottage?

The handover of the cottage on August 12, was widely reported both in the official proceedings of the Queensland War Council and in the local press. The Brisbane Courier reported that Mrs Woods was a widow ‘left to battle the world with five children, her husband having given his life for the Empire’. Finding the first occupant would not be simple with a name like Woods. Sixty-three persons whose surname was Woods died serving Australia in World War 1. If Wood is also a possibility, there are a further 103 servicemen to be considered. My search of their digitised service records failed to identify him.

Woods or Wood?

The key file is a batch of correspondence relating to the Anzac Workers Committee (QSA ID 267591). The file is far from a complete record and contains no information on the selection of the recipient for Anzac Cottage No.1. Presently the file is disorganised, but Queensland State Archives intends reinstating some order. A more painstaking search was more fruitful. The earliest material dates from July 1917 and includes the invitation from J Harry Coyne, Chairman of the Anzac Workers Committee to the Governor to perform the opening ceremony of the first Anzac Cottage "for a soldier's widow and the delivery of the key to her". With only one exception all of the many related reports refer to Mrs Woods. Only three items post-date reports of the handover. The first (August 23) concerns construction of fences around the land handed over to 'Mrs Woods'. The second in the Committee's minutes of 15th November 1917 is a reported enquiry from Mrs Woods (Enoggera Cottage) as to whether she was to pay for the pan and sanitary service (she was, from the time she took possession). The third dated 6th January 1918 is the only letter from the occupant of Kitchener Cottage, Everton Park advising that the fence is finished ‘at last’. Signed M Wood not Woods. She was hardly likely to get her surname wrong.

Which Woods were they?

It was simpler to start with the widow. Births on-line (assuming that the children were born in Queensland) for families with a minimum of four (which allowed for an additional child born after 1914), limited the possibilities for Wood to nine. Six of the husbands did not die in the War, leaving three. Of these, the only Thomas Wood who died was from NSW where his widow continued to reside. That left two, Mary Turner and Mary Wakefield, both of whose husbands were James Wood. One solider called James Wood, aged 29 years and 4 months in June 1915, died in November 1916. He was from Queensland, but which woman was his wife?

Which Mary was Mary Wood?

Mary Turner had six children, but the youngest died aged three, leaving five in 1914. However, her marriage in 1894 is impossible for James’ age to be 29 in 1915. The dates of birth for men enlisting were put up (by the young) and down (by the old) but it was unlikely that someone aged about forty would put his age back to 29. That left the likely wife as Mary Wakefield. Births on-line list five children, but one is a duplicate. However a further daughter was born in December 1915. When James Wood enlisted, his wife was pregnant. When Ethel Cecilia was born, Mary Wood had five children aged up to four years old. Further confirmation that M. Wood was Mary may be the Electoral Roll of 1919, which lists a Mary Wood (with home duties, but without a husband) at Everton Park, Enoggera. If correct, Mary Wood had changed the name of Kitchener’s Cottage to Gordonville.

Who was James Wood?

James Wood was born at Tiverton, Devon, England in 1886, the son of Frank Wood, then a mason at Turley, Devon but by 1911, a house builder in Sussex, and his wife Elizabeth Ann. It is not known when he arrived in Brisbane where in 1911, he married Mary Wakefield. On the 18th June 1915, aged 29, James enlisted for service in World War 1, and was posted as a private to the 4th reinforcements for the 26th Regiment. He was (for the time) of medium height (5’6”) but thickset (139lbs); had not served an apprenticeship and was without previous military experience. His occupation in 1915 was given as labourer. Next of kin was his wife who address . In January 1916, he joined the battalion at Tel-el-Kebir, the AIF’s training centre in Egypt. In March he embarked at Alexandria enroute to the Western Front, where the battalion carried out the first trench raid by Australian troops in June 1916, took part in the battle of Pozières in late July, and in appalling conditions of sleet and rain, at the final battle of the Somme, east of Flers, where James Wood was killed in action on 14th November 1916. His service record contains no details about his death, nor much else. Apart from missing an embarkation parade at Alexandria, he was never hospitalised, granted leave or absent without leave. Nor was he disciplined for any other reason. He is interred at the Warlencourt British Cemetery, Bapaume.

Who was Mary Wood?

Mary Wakefield was the eldest daughter of David Wakefield and Jane Cush. She was born in 1889 at Brisbane where she married James Wood in 1911. They may have been living at Rosecliffe St, Highgate Hill until 1913, but when their second daughter Margaret and second son Vernon were born in 1913 and 1914, they had moved to the country, probably Rockhampton. When James enlisted (at Brisbane) Mary’s address was 230 Dennison St, Rockhampton, a rooming house (now demolished). In September 1917, Mary’s address was changed to Everton Park, Enoggera from where she wrote asking if any other of her late husband’s possessions would be forthcoming. By April 1921, Mary had left Gordonville, and was living at Armstrong Rd, Cannon Hill. Some of her children continued to occupy the house after she seems to have re-married, to Robert Walker at Newcastle, NSW in 1928. If this was Mary Wood, she died at Petersham, NSW in 1944.

What happened to Anzac Cottage No.1?

The subsequently history of the Cottage has not been researched and it is not known when it was demolished. A photograph probably exists and may come to light. The original site is now occupied by two dwellings, whose addresses (from Google Maps) appear to be 9 Pullen Road and 680 South Pine Road.

A couple of months ago I was asked to speak about my research as the John Oxley Library Fellow. With so many architects and allied workers in consideration for the proposed dictionary, it was difficult to say much in the short time available. Instead I offered to speak about what I was working on at the moment the request to speak was made. It was the Anzac Cottages. I soon knew enough about them for my purposes, but it took longer to find my way out of the Woods.

Don Watson - John Oxley Library Fellow 2012

(with help from Stephanie Ryan, Jane Wassall, Joan Bruce, Myles Sinnamon and Barry Brown)

Comments

Your email address will not be published.

We welcome relevant, respectful comments.