Alma Moodie isn't a name that is etched into our cultural memory in the same way as other Australian born talents, very possibly because she left no recordings of her violin playing, or maybe because she spent the majority of her life in Europe. Those that know of her recognise her talent was tremendous and a gift to the world of classical music.

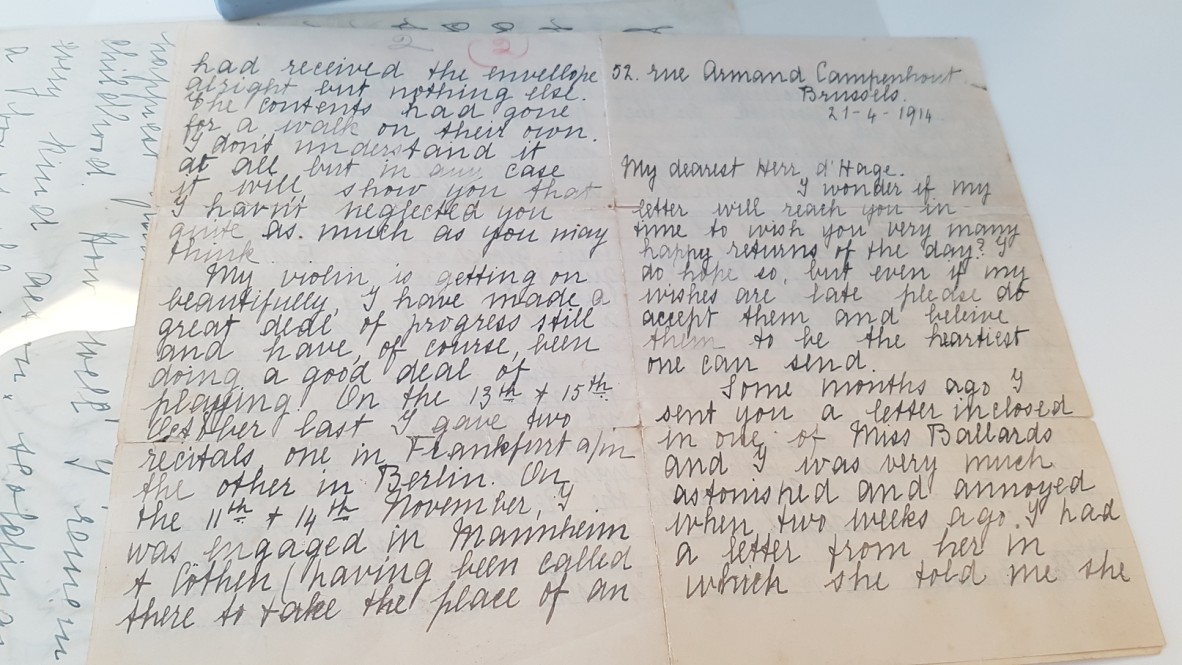

Her legacy however, is becoming more visible with the digitisation of four letters held by SLQ, written by Alma to Louis (Ludwig) D’Hage, her childhood music teacher in Rockhampton, between 1907 and 1923.

An only child, Alma was born in Mount Morgan, Queensland, to William Moodie and Susan McClafferty on 12 September, 1898. William died a year later and Susan, a music teacher, raised Alma and taught her violin from a young age.

By age 5 she was taking lessons in Rockhampton with Louis D’Hage, a Bohemian violinist, conductor and music teacher, and was playing public recitals by age 6. D’Hage trained in Vienna, came to Melbourne in 1880 for the Melbourne Exhibition, and stayed.

Alma left Australia for Brussels in 1907, after her exceptional talent secured a scholarship to the Brussels Conservatory at only 9 years of age.

The earliest letter we have is written in this year, with the exuberance and wonder of a child living abroad during the holiday season. Alma writes of her teacher telling her she must know her piece for the next day, not try, but know; and of the same teacher telling her the tone of her violin playing is dirty; she asks D’Hage to confirm it’s not.

By 1914 Alma was playing with Max Reger, a celebrated German composer, who said ‘hers was the biggest violin talent I have ever encountered.’

In her letter dated 21 April 1914, we get an insight into her concerto performance, as she writes about those who come to see her play in a packed theatre in Meiningen; a baroness and a prince and other dignitaries. She was told not to expect a warm reception, but her performance held no regard for such caution:

‘Reger warned me that the Meiningers are rather cold as the gentlemen are too aristocratic and the lady too frightened of cracking their gloves to clap. But I guess they forgot all about them when I had finished for a more unholy noise you can’t imagine. They were on their chairs and making themselves hoarse calling.’

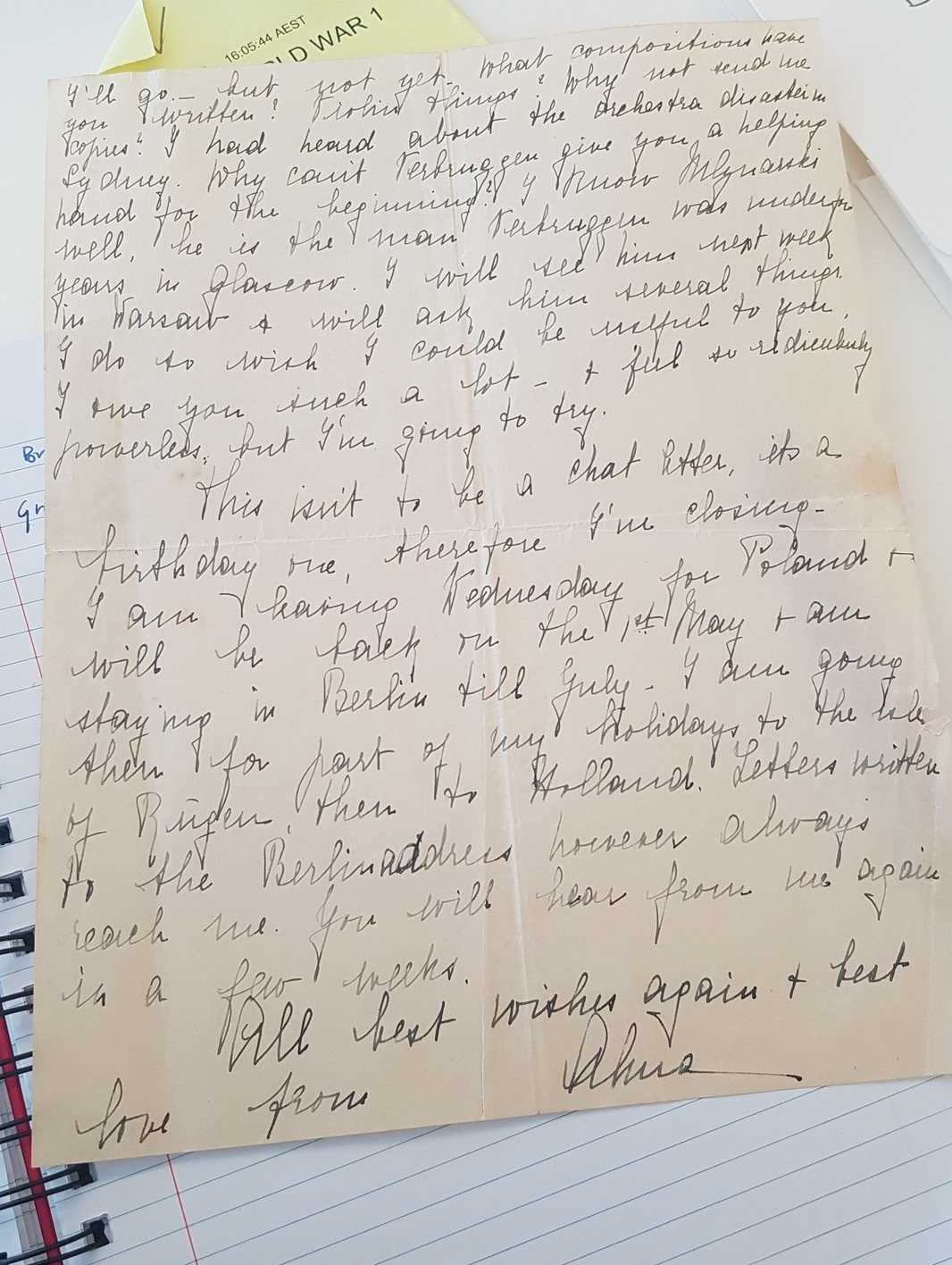

In a letter dated 13th April 1923, Alma had received a letter from D’Hage and is writing her reply, telling him about her punishing schedule of performing 70 times in seven months, and taking lessons in the spring with Carl Flesch (founder of the Carl Flesch scale system – a staple of violin pedagogy). The letter, sent from Berlin, reveals a maturity beyond her years:

‘Violin isn’t my only interest in life, and I don’t work to play publicly. I play only to be able to go on in what my real life is, and that consists of art all around, pictures, architecture, literature, languages; and my interests bring me in contact with the leading people in the different branches, and my art is big and strong enough to enable me to give to them… if I felt that I hadn’t the inner possibility of developing I would say, ‘well alright’, let’s go to America and earn money and play trash and be popular.’

Alma didn’t go to America, she stayed in Europe and went on to play with conductors including Hans Pfitzner, (who dedicated his Violin Concerto in B minor, Op. 34, 1923 to her), Wilhelm Furtwängler, Hans Knappertsbusch, Hermann Scherchen, Karl Muck, Carl Schuricht and Fritz Busch. Igor Stravinsky, widely known as the most influential composer of the 20th century, arranged a suite of excerpts from Pulcinella for violin and piano and Alma Moodie premiered it with the composer in Frankfurt on 25 November 1925.

Despite such acclaim, the tone of her letters conjures sympathy for young Alma, longing for the comfort of the paternalistic presence of D’Hage amidst the turmoil of WW1 and the death of her mother in 1918. The reader’s empathy soars at the loneliness that seeps into her sentences as the ink meets the page, and settles into admiration at the clarity with which she writes about her philosophy of playing violin.

Cover of Bluebeard's Bride, by Kay Dreyfus. 2013, Lyrebird Press. Held at John Oxley Library, SLQ.

Bluebeard’s bride by Kay Dreyfus is by far the most comprehensive biography of Alma Moodie, and is held in the John Oxley Library at SLQ. We have also compiled a list of Trove digitised newspaper articles mentioning Alma, spanning 1904-44. The lack of an obituary in any Australian newspaper after her death in Germany during WW2 in 1943 speaks to Alma's profile in Australia at the time. Fortunately, these letters, donated to SLQ by Louis D’Hage’s daughter, are a rare insight into the early years of Alma Moodie’s extraordinary life.

Collection Reference: OM80-78 Louis D'Hage Letters 1907-1923, John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland.

Comments

Your email address will not be published.

We welcome relevant, respectful comments.