Alaric - outback home of veterans

By Guest blogger - Tony Brett Young | 9 August 2018

In recent years a block of grazing land in Queensland’s outback 1,000 km from Brisbane has become a peaceful refuge for ex-service people who want to get away from it all. But Tony Brett Young recalls his lonely childhood in the late 1940s on the property that was then an isolated sheep station.

Alaric Veteran’s and Ex-servicemen’s Retreat is on a remote outback station of nearly 50,000 hectares nearly 100 km north of Quilpie. Its stated aim is to provide a secure and relaxing haven for veterans of all conflicts. According to its promotional material there are no formal activities - visitors can do as much or as little as they want. But there’s lots on offer for those who wish it, including opal fossicking, fishing, watching some of the 160 identified bird species, yabbying, reading, bush walking, watching television, or just relaxing with nature.1

Its very remoteness is part of the attraction, but for me as a very small boy, Alaric represented one of the loneliest periods of my life. Situated on the edge of Queensland’s Channel Country the property had strong connections with the pioneering Durack family. After the Great War large properties were cut into selections for wheat and wool production under the Closer Settlement and Soldier Settlement Scheme. Alaric, a block of about 12,000 hectares, had been selected by ballot by Chum Tully whose mother was a Durack. The story of the struggles of the families who pioneered the area are told in Dame Mary Durack’s Kings in Grass Castles.

Chum (his formal name) was a returned serviceman who had been badly wounded in France. Born in 1882 he enlisted at the age of 33. He sustained wounds to his left arm from a machine-gun burst, and later a depressed skull fracture, possibly from a shell which struck his helmet. There was a story that he always had a horror of beetroot because it reminded him of the grotesque injuries suffered by his comrades during the war.

Corporal. J.C. (James Chum) Tully. Published in The Queenslander Pictorial, supplement to The Queenslander, 19 August 1916

When Chum took on Alaric, conditions were primitive. There was no electricity, no phone, no radio and no motor vehicles. But there was piping hot water from a nearby bore nearly 1,000 metres deep. As corrugated iron was in short supply early accommodation was constructed of bush timber and malthoid, a type of felt sheeting impregnated with tar. Such huts served as utility rooms such as kitchen and dining room but tents were used for sleeping. Eventually Chum built a homestead with kitchen, dining room and lounge downstairs and bedrooms above. In the summer temperatures upstairs could sometimes reach 50C. because of the oven effect of the iron roof. Downstairs it was a comparatively cool 45 degrees. All the windows and doors were gauzed to keep out the flies, or that was the theory. Various flytraps were tried to combat the nuisance, with little success. And into the bargain sandflies and mosquitoes added to the torment of the early settlers.

Chum’s wife, Meta, was the daughter of a pioneering family from the district. Their only child, Pauline, was born in 1925. Sadly several other children did not survive and Mrs Tully’s own health deteriorated and she died in 1936. Chum died in 1944 and Alaric was left to Pauline, then aged 18.2 For some years she relied on managers to run the property, and she employed my father Ridley Brett Young for this purpose in 1946. He had worked with sheep in the Queensland outback since arriving from England as a young jackaroo in 1925. We came as a very young family - my mother, my brother Don aged 4, and me aged 2.

Pauline Tully at Alaric, near Quilpie, ca.1947. From Bell and Brett Young Family Papers. John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland

Don (left) and Tony with father Ridley Brett Young at Alaric, near Quiplie. From Bell and Brett Young Family Papers. John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland

My memories of Alaric are of a hot, dry, dusty, snake-infested, desperately lonely environment. All the time we were at Alaric my mother was particularly concerned about the danger of snakes and we were warned to avoid any possible hiding place for them. This concern transmitted itself to me, and to this day I have a fear of snakes of any sort. At night I would wake in a hot drenching sweat, always from the same nightmare in which I was chased endlessly by giant snakes.

We remained at Alaric for a number of years through fearsome drought, and periods of deluging rain. During times of drought my father would move sheep to agistment where there might still be food for them. After heavy rain there was no movement in or out or around the property for weeks. This was particularly difficult when the normal Saturday-afternoon delivery of mail and supplies could not reach us. And the rains also brought problems with the growth of rich pasture, and the sudden change from poor food to good brought the threat of bloat to our sheep, in extreme cases causing painful deaths.

When my brother Don was old enough he started correspondence lessons, taken by my mother who insisted that she was not a teacher, but who produced in us both a real thirst for knowledge through her own curiosity. I enjoyed sitting in on my brother's classes. Lessons were posted out each week from the Primary Correspondence School in Brisbane to be completed and returned. I recall especially the copybooks which introduced us to letters of the alphabet and which we duplicated as best we could. My brother’s efforts would be returned some weeks later stamped with a distinctive Australian animal to reward success and effort.

One of the curiosities of Alaric was the presence of a couple of opal fossickers who had a small lease on the property and who had carved out accommodation for themselves in the side of a hill close to where they were mining. We liked to go to see them at work and to ride into their mine on their rickety old trolley. One of them we knew as ‘Opal Joe’ who always welcomed us warmly, probably because we provided a distraction from his lonely occupation. On one occasion he presented my brother and me with large lumps of rough-cut opal. I still have mine today as a memento of his kindness.

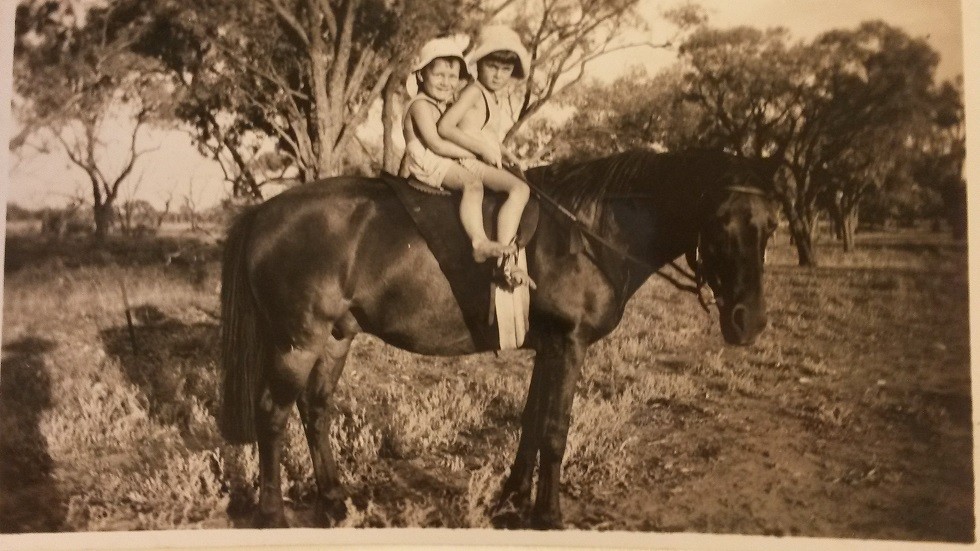

Tony (left) and Don Brett Young at Alaric, near Quiplie. From Bell and Brett Young Family Papers. John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland

Our stay at Alaric was to last nearly four years until my mother persuaded my father that she was no teacher, and was concerned about the need for proper schooling for my brother and me. We moved on to Longreach where my father became a government adviser in sheep husbandry for the district’s graziers. But that’s another story.

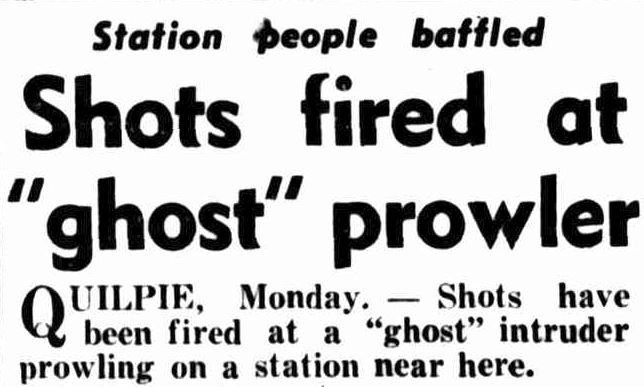

A year or so after we left Alaric, the property achieved a brief period of national fame with the appearance of what became known as the Alaric ghost. It was first spotted near the homestead over a number of nights and had the appearance of someone walking about with a large torch covered with a cloth. There was no response when attempts were made to contact the mystery person. Without warning the light would appear and disappear at different times and places. Then at about two o’clock one morning, a station hand saw a shadowy figure running from the back gate and fired a shot at it. Later it was found that the bullet had hit the ground about 30cm from the running footprint. Finally it was decided to involve the authorities, but the Alaric phone was down as a result of bush-fires and the then station manager drove to the neighbouring station, Buckabie, to call the police.

Over the next couple of weeks three uniformed police, a plain-clothed detective, two Aboriginal trackers, and a number of neighbours made widespread searches and enquiries but without success. One of the trackers, Willy Braddle, from Alice Springs was reported to be almost numb with fear because he suspected he was dealing with a ghost. However after being shown some tracks he followed them for a mile or so before losing them on the rocky ground. He did find evidence of other tracks, which suggested there had been even more unnoticed visits.2 The mystery of the Alaric ghost was never solved, but we followed the story for weeks in the Courier-Mail with particular interest and excitement.

Headline in The Courier-Mail, 29 January 1952, p.1

During our time at Alaric we came to know the owner, Pauline Tully, extremely well and she was always particularly kind to us as children. After we moved away she married Michael O’Callaghan and they continued to run Alaric for many years until the property was sold in 2006. Pauline died in 2011 in Alexandra Headlands where she had moved in retirement. 3

With the sale of Alaric the new absentee owners had no real need for the five-bedroomed homestead that we had lived in, and it seemed destined to fall into decay until a Vietnam veteran happened to hear about it. He negotiated a deal with the new owners to allow the building to be restored for use as a retreat for Australian service veterans. The restoration work was carried out by volunteers and since opening the Alaric Retreat has regularly attracted former service people from all parts of Australia.

I discovered this new role for Alaric several years ago when googling the name out of curiosity. I instantly recognised the homestead shown on the website as I have a photograph of it taken from same position in the late 1940s. There seems to be an appropriate symmetry about the early life of Alaric homestead built by a wounded veteran of the Great War, and its reincarnation as a retreat for veterans from later Australian conflicts. I feel Chum Tully would certainly have approved.

Tony Brett Young

NB - The Bell and Brett Young Family Papers are currently being processed and will be available to view at State Library in the coming months.

References

1 http://vietnamvetssc.org.au/alaric-station-veterans-retreat/

2 A Strange and Distant Land by Malcolm J E Brown Privately published in 1999

3 Deaths & Funerals - The Courier Mail 04 June 2011

Comments

Your email address will not be published.

We welcome relevant, respectful comments.