Guest blogger: Dr Martin Kerby - 2018 Q ANZAC 100 Fellow.

The photographs taken by Frank Hurley of the shattered landscape during the latter part of the Third Battle of Ypres (31 July-10 November 1917) are the Western Front for many Australians. It is ‘as if the soldiers were doomed, in a parody of the Flying Dutchman, to continue to fight their hopeless battles in the mud of Flanders for ever’.1 Yet despite the continued impact of Hurley’s images and the fact that twenty percent of all Australian deaths in war occurred in 1917, the battles of 1917 occupy a ‘strangely ambiguous’ place in the collective memory.2 Passchendaele, as the battle became known, occurred during a period in which Australian politics was conducted in a bitter and divisive atmosphere. In particular, Queensland was a deeply polarised society3 derided as the ‘arch-home of everything anti-Empire and anti-Australian’ (National Leader, 1919).

In a number of important ways Queensland’s experience of war was, if not entirely unique among the Australian states, certainly subject to a variety of heightened pressures. From May 1915 it had the only Labour government in the Commonwealth and the only one in the Empire to oppose conscription. Evidence of radicalism in Queensland, no matter how marginalized, appeared to justify conservative fears of a ‘collusive cadre of disloyalist conspirators’4, one which included the Australian Socialist Party, the Industrial Workers of the World, pacifists, Irish Catholics, Bolsheviks, trade unions, and anti-conscription advocates. In addition, Queensland was home to Australia’s largest Irish and Russian minorities and accounted for 31 percent of the Australian males of enemy birth or parentage; the Easter Uprising, the Russian Revolution and the anti-German rhetoric therefore intersected with domestic concerns particularly strongly.

The Queensland Press and Passchendaele

In spite of the domestic divisions a belief in the courage and skill of the Australian soldier was something of an article of faith among Australians. This pride, and the grief at the mounting casualties, meant that war news from Europe was almost quarantined from the more contentious world of domestic politics, at least as far as the press was concerned. The reports of the fighting appearing in Queensland newspapers, and they were numerous and detailed, are significant for their studied avoidance of anything other than the battlefield. The Australian infantry entered the battle proper during the Battle of the Menin Road (20 - 25 September), which was then quickly followed by four further battles - Polygon Wood (26 September - 3 October), Broodseinde (4 - 7 October), Poelcappelle (9 - 10 October) and First Passchendaele (12 - 13 October). Taking advantage of drier weather and the use of a step by step approach against the pill boxes and fortified strong points now adopted by the Germans, the first three were successful in reaching their objectives, though the final two were a shambles. It cost the Empire 300,000 casualties. For the AIF it was the most costly of all of its campaigns; between July and November 1917 it suffered over 38,000 casualties.

The Newspaper Reports

The early fighting was a cause for celebration in the press, though success was usually couched in relational terms that positioned Australian troops as leading their allies or defeating their enemies - ‘Australia in the Van’, ‘Germans Outclassed’ (Queenslander, 29 Sept., 1917, p. 39), ‘Storming troops at the fighting centre’, and ‘Invincible Australians’ (Warwick Examiner and Times, 22 Sept., 1917, p. 4). Gordon Gilmour assured his readers that this was ‘the greatest Australian battle, both in the magnitude of the struggle as a whole and the number of Australians engaged’ (Brisbane Courier, 24 Sept. 1917, p. 7). Even Charles Bean, who found Gilmour’s reports overwrought, agreed that the battle was one of the ‘greatest the British arms ever fought’ (Daily Mercury, 30 Oct. 1917, p. 3). Headlines in regional centres were hardly less effusive - ‘Australians Cover Themselves in Glory’, ‘Big Tactical Success’ (Warwick Examiner and Times, 22 Sept. 1917, p. 4), ‘Success all along the Line (Townsville Daily Bulletin, 24 Sept., 1917, p. 4), ‘Honour for Australians. Selected as storming troops’, and ‘German Debacle may be near at hand’ (Darling Downs Gazette, 22 Sept., 1917, p. 5).

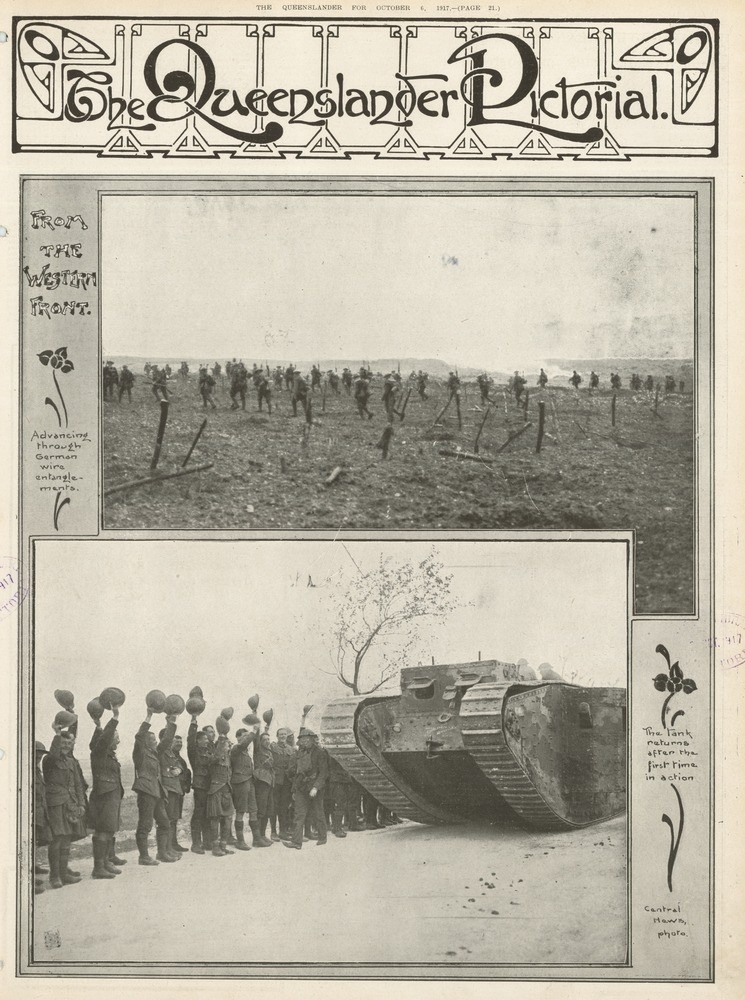

Page 21 of the Queenslander Pictorial supplement to The Queenslander 6 October 1917. John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland. Image 702692-19171006-0021

The emphasis on the battle’s significance reached its apogee during the Battle of Broodseinde. Percival Phillips crowned it the ‘most important battle of this campaign, if not of the war the finest troops of the British Empire dealt a crushing blow, striking together with splendid precision and determination’ (Darling Downs Gazette, 8 Oct. 1917, p. 5). Editors in Australia were equally enthused, running headlines such as ‘Our Victory Complete’, ‘Germans reeling under smashing blow’, ‘Crushing German defeat’, ‘May be war’s turning point’ (Telegraph, 6 Oct., 1917, p. 6), ‘Greatest Victory of the War’, and ‘Anzacs add to their laurels’ (Darling Downs Gazette, 8 Oct., 1917, p. 5). Keith Murdoch crowned it ‘the greatest day Australia has had in Europe’ (Daily Mail, 8 Oct., 1917, p. 5) during which ‘Irresistible Anzacs’ had defeated ‘German Picked Troops’ (Daily Standard, 8 Oct., 1917, p. 1).

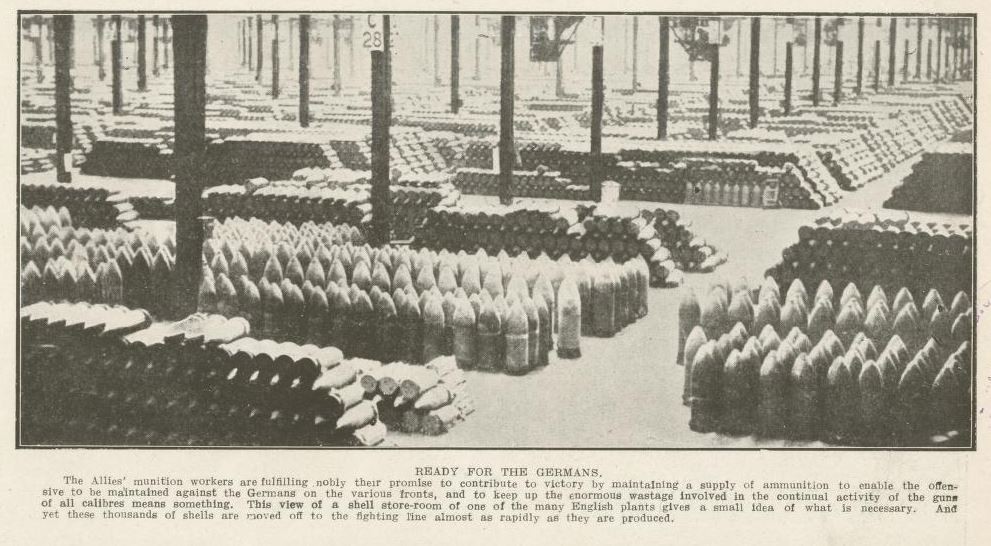

Allies' munition factory. Page 27 of the Queenslander Pictorial, supplement to The Queenslander, 22 September, 1917. John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland. Image 702692-19170922-0027

Broodseinde was, however, a false dawn. The rain, which had started to fall on the first day of the battle, had become torrential by the 8th. Nevertheless, Haig pursued the offensive at Poelcappelle and First Passchendaele to its inevitable and tragic conclusion. The tone of the press reports altered to reflect these dashed hopes, with Bean’s being a case in point. Although one of his reports still appeared under the headline ‘Another Great Day’ (Darling Downs Gazette, 13 Oct., 1917, p. 5), he was free to refer to ‘wild storms, bitter weather and penetrating driving rain’, the battlefield being ‘a wilderness of mud’ (Daily Mercury, 18 Oct., 1917, p. 3), and the ‘difficulty of the mud and the exhaustion of the men’ (Townsville Daily Bulletin, 12 Oct., 1917, p. 4). Other papers ran headlines that were even more direct - ‘Mud Everywhere’ (Darling Downs Gazette, 9 Oct., 1917, p. 5), ‘Mud Worse than the Germans’, ‘The Awful Mud Prevents us making best use of victory’ and ‘The Rain Again Hampers another thrust in Flanders’ (Warwick Examiner and Times, 13 Oct., 1917, p. 4 ).

Honouring fallen soldiers at Yeronga Park. Page 28 of the Queenslander Pictorial, supplement to The Queenslander, 22 September, 1917. John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland. Image 702692-19170922-0028

This change in tone could not have escaped the attention of Queenslanders, who for almost two weeks read numerous reports describing ‘seas of mud’, ‘soldiers waist deep in thick slime’, ‘wind howl across Flanders with long sinister ragings’ (Queenslander, 20 Oct., 1917, p. 37), British and Australian soldiers navigating ‘the mud seas and mud mountains like miracle men’ (Queenslander 20 Oct., 1917, p. 37), and shell craters ‘brimming over into swamps of mud’ (Queenslander, 13 Oct. 1917, p. 37). As the attack stalled, the emphasis shifted to the Australian soldiers’ ‘undiluted heroism if the results of the fight are no more incomplete than previous ones, the extreme endurance which they had to show was far greater’ (Townsville Daily Bulletin, 12 Oct., 1917, p. 4). The men ‘went on without a whimper under the worst possible conditions and were not afraid of the worst punishment the Germans have to offer’ (Queenslander 20 Oct., 1917, p. 37).

Yet through it all, in spite of domestic upheaval in a state derided as disloyal, and in the face of mounting casualties, the mythology of the Australian soldier made him immune from press analysis, let alone criticism, whether it be overt or implied. As some political commentators have found to their cost during the centenary commemorations of the First World War, the AIF remains almost above criticism, enshrined as it is in communal memory as the archetype of all that is good about Australia and Australians.

1 Andrews EM (1993) The Anzac Illusion: Anglo-Australian Relations during World War 1. New York: Cambridge University Press, p. 3

2 Beaumont J (2013) Broken Nation: Australians in the Great War. Sydney: Allen & Unwin, p. 391.

3 Evans R (2007) A History of Queensland. New York: Cambridge University Press.

4 Evans R (1987) Loyalty and disloyalty: social conflict on the Queensland homefront, 1914-18. Sydney: Allen & Unwin.

Dr Martin Kerby - 2018 Q ANZAC 100 Fellow

Comments

Your email address will not be published.

We welcome relevant, respectful comments.