Vegetables Directly from Creek to Table: Chinese Market Gardens in Brisbane

By Christina Ealing-Godbold, Research Librarian, Library and Client Services | 10 August 2023

The Chinese contribution to the state of Queensland took many forms – Chinese people worked as miners, shepherds, traders, furniture makers and labourers. Chinese labourers first came to Queensland as shepherds and then in the 1870s, as miners for the “New Gold Mountain” on the Palmer River and other diggings in Queensland.

However, their contribution to Queensland came in a much more humble form - fresh vegetables and fruit for the householder, delivered to the door. It has been said that early Queensland towns and cities would not have survived without fresh food from the Chinese gardeners!

The Chinese met with racism. Journalists described the immigrants as “celestials”, “heathens” and “mongol hordes” as they questioned their right to mining claims, land and jobs. By 1877, restrictions meant that Chinese miners could only have access to mining claims after the land had been worked for three years by European labourers. Further racism and restrictions culminated in the White Australia Policy of 1901, where Chinese people in Australia were labelled as aliens, controlled by police, and new immigrants were subjected to dictation tests in any European language.

Following the indentured labour schemes and the thrill of the chase of gold, Chinese people became market gardeners, storekeepers, cooks, business owners and apothecaries and became important members of Queensland communities. However, they were still prevented from owning land and had to lease the land for their market gardens. After the war, land leased by Chinese market gardeners in the north of the state was resumed and given to Soldier Settlement applicants. Always adapting to their environment, many Chinese people then moved away from the land and became storekeepers or business owners.

Chinese Market Gardens in Brisbane

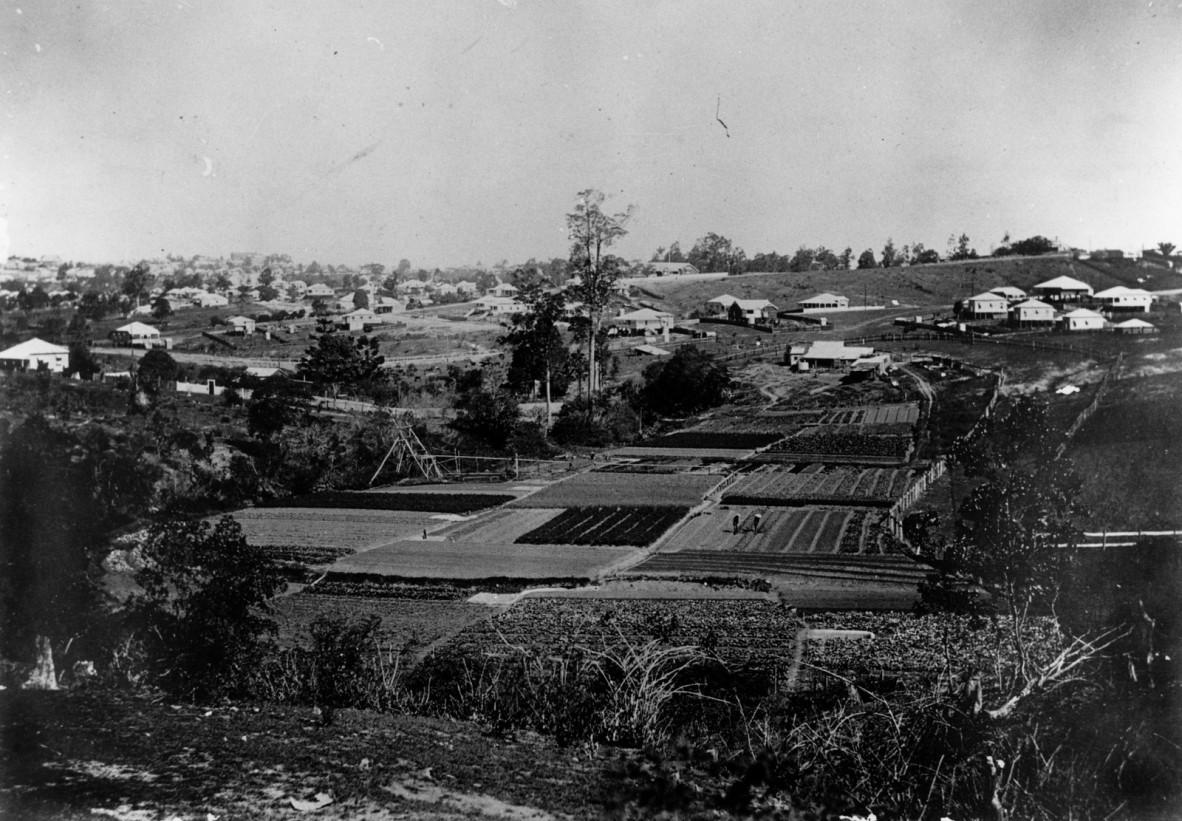

Chinese gardeners, mostly male, leased land near watercourses throughout Brisbane and grew vegetables and fruit. The gardeners lived in rough wooden huts on the land, adjacent to their crops. They tendered and irrigated their vegetables carefully and thoroughly. The produce was sold from door to door by the Chinese vegetable gardeners.

Extensive Chinese gardens could be found adjacent to Enoggera, Kedron Brook, Breakfast and Ithaca creeks – each garden laid out in methodical rows with wooden irrigation devices erected to bring water up from the creeks. Ekibin, Fairfield and Mt Cotton were also places where Chinese gardeners thrived on leased land. In country towns throughout Queensland, the Chinese could grow vegetables where there was very little water and in times of drought, it was only the Chinese vegetables that kept the town well fed.

Land was selected near a watercourse, where the soil was laden with nutrients from flooding and heavy rains. When the water course dried up, the Chinese dug wells to find the much needed moisture. Wooden structures used pulley systems and natural leverage to draw water from wells and creeks. Always in neat rows, there were no weeds or stray vegetation among the rows of cabbages and radishes. Each garden was tendered by a group of Chinese men and tasks were assigned – one to weed, one to water, one to add manure and one to sell the vegetables door to door.

White Australia and Chinese Produce

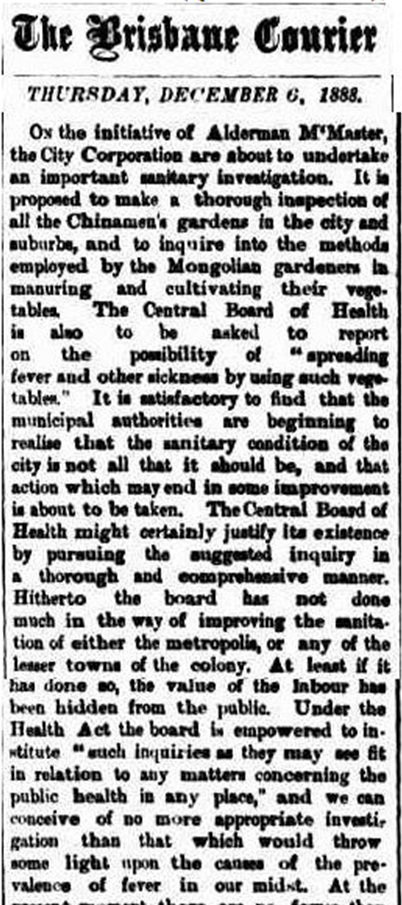

The concern that the Chinese were taking jobs and markets away from other Brisbane residents was a constant topic in the newspapers of the 1880s through to the first World War. The healthy, large well -irrigated cabbages, radishes, lettuces and other produce grown by the Chinese were cheaper and larger than items provided through fruit and vegetables stores. The strategy used to improve the markets for white market gardeners was to question the manure that was being used to produce these giant vegetables grown by Chinese people. Housewives would be put off buying the vegetables from Chinese gardeners if it was shown to be unclean or questionable.

Each gardener possessed a jar in which manure was collected. Brisbane residents became fascinated with what was in the jars and even started rumours that it was human excrement, such was the racist attitudes of the time. Despite concerns, health officials could not find any problems with the growth of the vegetables (aided by the contents of the jars). Experts were consulted and in 1888, an investigation by Mr McMahon of the Botanic Gardens was conducted.

Medical doctor, Dr Bancroft was also consulted – some feared that typhoid and other diseases, even possibly leprosy may come from eating the vegetables. Dr Bancroft lived at Kelvin Grove, adjacent to the Chinese Gardens but could not attribute any specific disease to the Chinese vegetables.

Finally, in 1904, the Commissioner of Public health, under the Queensland Health Act of 1900 regulated the gardens, insisting that vegetables that were not washed in water and may be infected by slaughterhouses or tanneries, must be stored in a well-ventilated shed, vehicles used in the conveyance of the vegetables must be kept clean and manure or offal must not be buried near the banks of creeks where it could infect the water. It was also decided that piggeries must not be adjacent to water supplies and that liquid manure must not be used to fertilise the vegetables. The penalty for breach of the regulations was 20 pounds and placards written in Chinese, outlining the regulations and bylaws were to be displayed at various relevant places such as Breakfast Creek and Kelvin Grove. (Brisbane Courier (Qld. : 1864 - 1933), Friday 4 November 1904, page 4)

Nevertheless, Chinese market gardens operated in creek side land in Brisbane up until the 1940s and some even later. Generally, Chinese people who married established themselves in stores or other industries. The market gardeners were mostly unmarried men. There were moves to exclude Chinese people from the Brisbane markets and many of the market gardeners delivered directly to the door.

Those who were later able to use the markets took their produce to Roma Street markets in a horse and cart.

Chinese Family History – unlocking the history of the market gardeners

Finding the history of the market gardeners and following family history is a difficult task. Firstly, the names were spelt in many different ways and a Chinese man could take various names throughout his life journey. Chinese names consisted of a family name, a personal name and a generational name. In addition, names like Johnny or Tommy were often added to part of the original name. The title “Ah” was affixed to the front of the family name, as an honorific, akin to using the word “Mr” or “Sir”. Once established in a store and with a family, Chinese Queenslanders can be found in Post Office Directories and suburban histories. However, those single men who were employed by others to work on market gardens are well hidden to family history. If they contravened the law by gambling, smoking opium in their huts or drinking, they may appear in the newspapers but generally with a simplified name that made them difficult to trace – e.g. Ah Chew or Ah King.

Some identified gardeners in the northern suburbs of Brisbane were:

Ah King at Serpentine Road Ashgrove; Ah Sung who lived in Three Mile Scrub Road (now Ashgrove Avenue); Gee Gong (known locally as Chicky) who lived off Waterworks Road, known as “Waterworks Road Gardens” in the 1930s. Gee Gong pumped water from the creek and kept it in holding ponds and Ah Jung also lived and worked at Waterworks Road gardens. The Sue Tin family had a well- known shop at Boondall but David Sue Tin had a market garden in Quandong Street, Ashgrove and Mathew Sue Tin had his gardens in Bishop Street. Ah Lum sold fruit door to door at Breakfast Creek.

The market garden in Bishop Street Kelvin Grove had a number of Chinese residents and was the one referred to by Dr Bancroft as being the gardens opposite his home in Kelvin Grove. George Ah Gow lived across the road in Kelvin Grove with his family but leased land near Enoggera Creek at Bishop Street for market gardens and also sub leased some of it to Ah Yew and Ah Yang. This area of Bishop Street was the site of market gardens until World War Two. For more than one hundred years, these market gardens by Enoggera Creek flourished and were replenished by each flood and heavy rain.

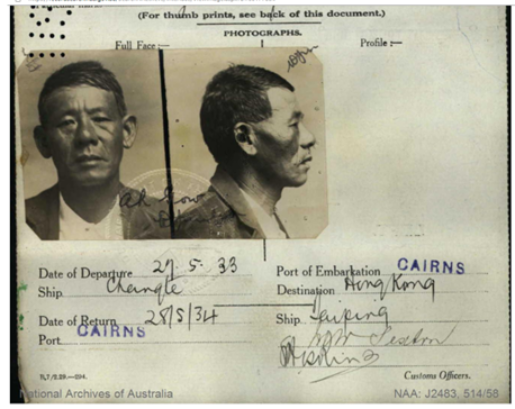

Family history tools available for the study of Chinese family history include all those regularly used - the Trove newspaper database, Births, Deaths and Marriages Queensland, Post Office directories on Ancestry.com and local histories. In addition, the Register of Aliens in Queensland (1913) may be helpful. Many Chinese men travelled home to China and returned. After 1901, it was necessary that they applied for a Certificate of Domocile and Certificate of Exemption from the Dictation Test, available by searching online at the National Archives of Australia. These records contain photographs and can be a useful addition to family history, sometimes listing alternate names and also the date when the person first entered Queensland.

Certificate of Exemption from Dictation Test, National Archives of Australia

The Chinese contributed much to Queensland society. In the suburbs of Brisbane in the late 19th century and up to mid - 20th century, most residents had contact with Chinese people through the purchase of fresh vegetables and fruit. However, in many cases, the gardeners who grew them remain a mystery.

Recommended reading

Books

- Chinese market gardening in Australia and New Zealand: garden of prosperity by Joanna Boileau (2017)

- Chinese market gardens and gardeners on Enoggera Creek and Ithaca Creek by Desley M. Drevins (2007)

- Under the Southern Cross: contributions of senior Australian Chinese in Queensland edited by Ron Li and Mingxian Su (2000)

- Ancestral leaves:a family journey through Chinese history by Joseph W. Esherick (2011)

Articles

- 'Cultivated with great carefulness': Chinese market gardening, urban food supplies and public health in Australasia, 1860s-1950s by James Beattie and Joanna Boileau (New Zealand Journal of History, 2020)

- Roots of racism: the Chinese experience in early Brisbane, 1848-1860 by Rod Fisher (Australian Society for the Study of Labour History, 1990)

- Rewriting the history of Chinese families in nineteenth century Australia by Kate Bagnall (Australian Historical Studies, 2011)

More information

One Search catalogue – https://onesearch.slq.qld.gov.auopen_in_new

Library membership – https://www.slq.qld.gov.au/services/membership

Plan your visit – https://www.slq.qld.gov.au/visit

Ask a librarian - https://www.slq.qld.gov.au/services/ask-librarian

Comments

Your email address will not be published.

We welcome relevant, respectful comments.