Oodgeroo Noonuccal: Remembrance Day 2024

By Alice Rawkins, Engagement Officer, Anzac Square Memorial Galleries | 29 October 2024

Oodgeroo Noonuccal, born Kathleen Jean Mary Ruska, was one of 4,000 First Nations Australians who served during World War II. Described by Australian author Nancy Cato AM as 'small but tough, with a wonderful resilience and a great sense of dedication' (1993), Oodgeroo was a civil rights activist, poet, environmentalist, educator, and veteran. While well-known for her activism and poetry, her wartime contributions with the Australian Imperial Forces (AIF) are often overlooked.

Oodgeroo Noonuccal in full Australian Women's Army Service uniform, 1940.

Oodgeroo was born on 3 November 1920 at Bulimba. She was the second youngest of 7 children to Edward (Ted) Ruska and his wife Lucy, née McCullough. Her father Ted, a Quandamooka man from the Noonuccal clan on Minjerribah (North Stradbroke Island), was the foreman for a group of First Nations labourers employed by the Queensland Government. Her mother Lucy was part of the Peewee Clan from inland Queensland and had been removed from her family at the age of 10 following the death of her Scottish father. She was placed in an institution in Brisbane where she was taught domestic skills rather than to read and write. At 14 years old, Lucy was consigned to work as a housemaid in rural Queensland. She bitterly resented being denied the opportunity to develop literacy skills.

Oodgeroo’s childhood home was at One Mile on Minjerribah. It was here that Ted taught his children to respect their heritage as Noonuccal people. This was also the setting for Oodgeroo's earliest memories of hunting wild parrots, boating, fishing, and sharing in the community dugong catch. She attended school at Dunwich State School and excelled at reading and writing. No doubt inspired by her father, who told her that, as a First Nations Australian, she didn’t have to be as good at her school lessons as the white children—she had to be better. In 1934, at 13 years old, Oodgeroo finished her formal education and began working as a domestic servant for a white family in Brisbane, earning two shillings and sixpence (25 cents) per week. When she was 16, she was denied the chance to train as a nurse because of her heritage as a First Nations Australian.

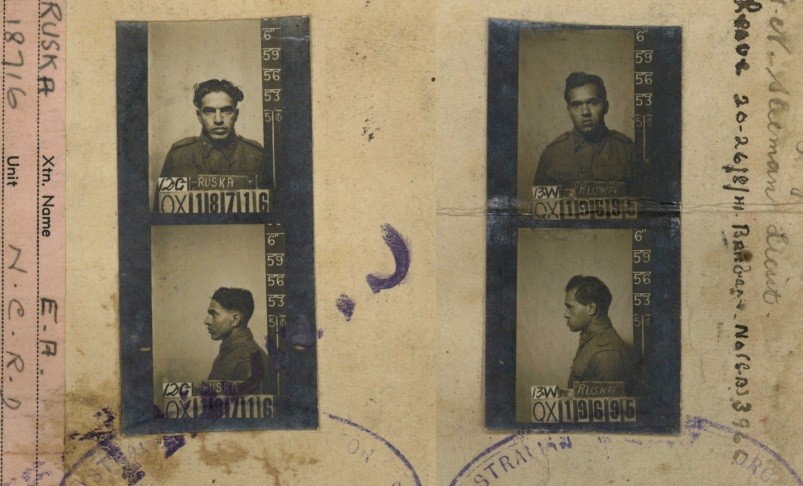

Oodgeroo's brothers, Edward Allen Ruska (left) and Eric Victor Ruska (right), courtesy of National Archives of Australia.

When World War II began, the Ruska family responded to the call for volunteers. Two of Oodgeroo’s brothers, Edward and Eric, joined the army and were assigned to the 2/26 Infantry Battalion. Both her brothers were captured during the fall of Singapore and would spend the remainder of the conflict as Japanese prisoners of war. Her parents did their bit for the war effort by throwing open their home to soldiers and construction workers. In December 1942, at the age of 21, Oodgeroo enlisted in the Australian Women’s Army Service (AWAS) and trained a signaler. The AWAS was a non-medical women’s service established in Australia during World War II. Raised on 13 August 1941 to release men from certain military duties for employment in fighting units, the service grew to be over 20,000 strong and provided personnel to fill various roles, including administration, driving, catering, signals, and intelligence. After war’s end, the service was demobilised and ceased to exist by 1947.

Studio portrait of Oodgeroo Noonuccal, 1942, courtesy of Australian War Memorial.

Oodgeroo, like most Australians, had a variety of motivations for joining the war effort. Her main reason, as she would later recall, was:

'I joined up firstly, because I don't like fascism and secondly, because my two brothers had been taken prisoners of war and I felt guilt about that. Here I was, sitting at home very secure and not pulling my weight. So I ended up in the Australian Women's Army Service'.

(Hall 1995:116)

She was also motivated by a great desire to escape life as a domestic servant. The armed forces offered education courses and the opportunity to acquire job skills that were otherwise inaccessible for most First Nations peoples. This was highly appealing to Oodgeroo, who explained:

'I had been working as a domestic for two shillings and sixpence a week before I joined the Army. You see, Aboriginals weren’t entitled to any extra concessions of learning and it was the Army who changed the whole thing around … and it was the only way that Aboriginals could learn extra education at that time. And so, that was one of the reasons' [for enlisting in the Army].

(Hall 1995:113)

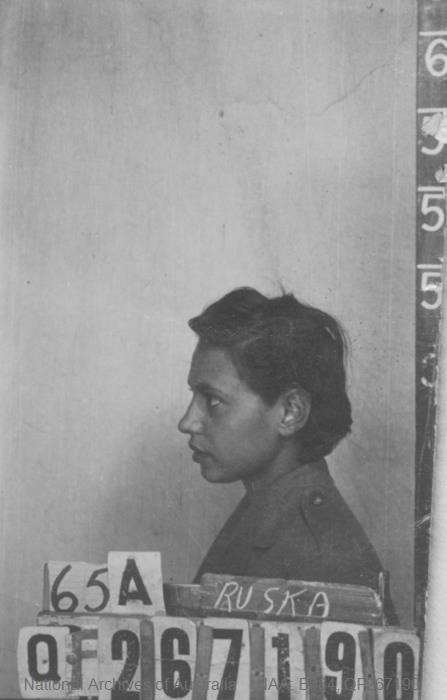

Kathleen Jean Mary Walker, black and white ID, courtesy National Archives of Australia.

In December 1942, Oodgeroo completed her basic AWAS training at Indooroopilly. She was then attached to No 1 Company, Queensland L of C Sigs, in January 1943, and trained as a switchboard operator at Camp Chermside in Brisbane, before being assigned to the Army Headquarters in Ann Street Brisbane. She rose through the ranks, was promoted to Lance Corporal in April 1943, and later worked in the pay office. She was very well-liked with her commanding officers speaking highly of her service. In May 1943, she married her childhood friend, Bruce Walker, who was a talented bantamweight boxer and welder by trade. Following her marriage, she chose to remain with the AWAS and was placed in charge of training new recruits. She was discharged in January 1944 due to chronic ear infections that had led to partial deafness. She was a member of the Australian Legion of Ex-Servicemen & Women until 1946.

Women in training for the Australian Women's Army Service, Brisbane, August 1942.

When Oodgeroo first enlisted, she was warned that she might experience racial abuse in the armed services, but her wartime experience was the opposite. She joined sporting teams and made friends, including with Eris Valentine and Thora Travis, two white Australians. It was the first time that Oodgeroo would experience what it was like to live with white people who didn't notice the colour of her skin. In a speech she later wrote:

'I was accepted as one of them and none of the girls I trained with cared whether I was black, blue, or purple. For the first time in my life, I felt equal to other human beings'.

(Riseman 2018:144)

The war was an equalizer and fostered an understanding, respect, and cooperation between First Nations peoples and white Australians, which had not been seen before. According to Oodgeroo:

'In the Army they didn’t give a stuff what colour you were. There was a job to be done … and all of a sudden the colour line disappeared'.

(Hall 1995:118)

While serving, she also socialised with African American soldiers stationed in Brisbane, regularly attending dances at the Dr Carver Service Club in South Brisbane. These interactions were influential in her advocacy for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples rights later in life.

Australian Women's Army Service members marching.

Sadly, the racial equality she had experienced as a servicewoman did not last when she returned to civilian life. Later in life, she would recall:

'After I took my uniform off, I went back to being a second-class citizen. White Australia is ignorant of Aboriginal involvement during war'.

(Canberra Times 1993:2)

In December 1945, she wrote to the Editor of a local newspaper, arguing the existence of a non-official colour ban in some parts of Queensland. She had experienced this colour ban first-hand, when staff at a cinema in Scarness (Sunshine Coast), refused to sell her a movie ticket unless she agreed to sit at the back of the theatre. She argued to the editor that:

'I can only conclude that my colour was the drawback. I might say that I was an A.W.A.S and my two brothers fought in this war. They were in the hands of the Japanese for over four years and one brother lost a leg fighting for so-called freedom and democracy'.

(Maryborough Chronicle, Wide Bay and Burnett Advertiser 1945:19)

It was these experiences of discrimination that drove Oodgeroo to advocate passionately for equality for First Nations Australians.

Following her discharge from the AWAS, she joined the Communist Party of Australia, which was the only political party at the time that did not support a White Australia Policy. Here, she developed skills in public speaking and political strategy, which she would continue to use for her advocacy. Her association with the communist party led to her being closely surveilled by officials, with these records now available through the National Archives of Australia. She eventually left the party because they wanted to write her speeches.

Oodgeroo’s marriage to Bruce ended in 1947, shortly before the birth of their son Denis, due to domestic violence. She then participated in the Army’s post-war rehabilitation program and received training in secretarial work and book-keeping. While this led to an office job, she struggled as a single parent, and returned to the flexible hours of ironing and cleaning professional households. She eventually took a job with Sir Raphael and Lady Phyllis Cilento. In 1953, she gave birth to a second son Vivian; his father was Raphael Cilento Jnr. The Cilento’s never acknowledged Vivian.

Oodgeroo Noonuccal at her caravan home Moongalba on North Stradbroke Island, Queensland, 1982.

In the 1960’s, Oodgeroo developed a reputation as a poet, publishing three highly acclaimed collections including We Are Going, which featured poetry and themes exploring Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples dispossession and racism. It was around the same time that she increasingly began advocating for the rights of First Nations peoples, working tirelessly in the 10 years prior to the 1967 referendum, to raise awareness. She would spend the rest of her life working toward reconciliation, which she acknowledged was 'a long and lonely road, but oh, the goal is sure' (Walker 1970:54).

Len Waters and Oodgeroo Noonuccal standing in front of an Australian Aboriginal flag participating in a march, 1980.

In 1970, Oodgeroo was appointed a Member of the British Empire, for her services to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. She returned this award in 1988 to protest the celebrations planned to mark 200 years since the arrival of the first convict ships in Australia and began using her traditional name, Oodgeroo Noonuccal. She struggled with ill health for many years before passing away from cancer in 1993 at Greenslopes Hospital. She was buried on her beloved Minjerribah beside her son, Kabul (Vivian), who had tragically died two years earlier from AIDS. It is said that, when the barge was taking the hearse and mourners over to Minjerribah for the burial, the captain pointed out something he had never seen before. Two whales were swimming in front of the vessel, all the way to the Island, guiding Oodgeroo home one last time.

Oodgeroo Noonuccal being interviewed at an exhibition in Sydney, circa 1982.

This Remembrance Day, we remember Oodgeroo Noonuccal for her World War II service and tireless work for First Nations Australians. We encourage you to think about who you'll stop to remember and discover ways to commemorate Remembrance Day at Anzac Square & Memorial Galleries

Further reading and references

Comments

Your email address will not be published.

We welcome relevant, respectful comments.