Maino – The Last Mamoose of Yam Island, Torres Strait

By Tania Schafer, Librarian, State Library of Queensland | 3 November 2021

Cultural Care statement (disclaimer)

Users are advised that this Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander material may contain culturally sensitive imagery and descriptions which may not normally be used in certain public or community contexts. Annotation and terminology which reflects the creator's attitude or that of the era in which the item was created may be considered inappropriate today. This material may also contain images, voices or names of deceased persons.

Image from Drums of Mer by Ion Llewllyn Idriess page 319

Some great leaders find responsibility thrust upon them unexpectedly and rise to the occasion, while others are born knowing that their destiny lies in greatness.

Maino Kebisu was a man where both are applicable. Born sometime in the mid-1800s, Maino was the son of the warrior Kebisu, a leader born on the island of Tutu/Tudu. Tudu became known as Warrior island in the early 1800s, owing to the violent clashes between the islanders and the European sailors exploring the area.

In the 1860s, William Banner constructed a Beche-de-mer (Sea Cucumber) processing facility on the island. While previously hostile to these visitors to their islands, Banner fostered friendly relations with the local islanders, who were then led by the warrior Kebisu.

While no photographs exist of Kebisu the elder, a description of him in Drums of Mer, an embellished story of life in the Torres Strait by Ion Llewellyn Idriess, paint him as an absolutely striking man:

“his stature emphasized by enormous shoulder muscles, limbs long and powerful, his bearing sheer untamed arrogance, his face unexpectedly pleasing because of boyish happiness which occasionally lightened his grim jaw and broad, savage cheeks. With a full brow of ringlets that fell upon his shoulder, arranged to hide the fact that the left ear was missing, bitten off in a fight.”

Idriess goes onto describe Kebisu as the greatest organizing genius that the Torres Strait Islanders had ever known. Both for war and for trade, he made his small island of Tudu the key position for all commerce that came from far down the Australian coast, and right across the length and breadth of the Strait to New Guinea’s shores.

In the 1870s, the government named Kebisu the ‘Mamoose’ of Tudu island, a Torres Strait Islander term for “Chief of the tribe’. The Mamooses were appointed to be leaders and representatives of the government on their respective islands. When Kebisu died in 1885, Maino, the favourite son of Kebisu, was named the new Mamoose of this strong and influential community of Tudu.

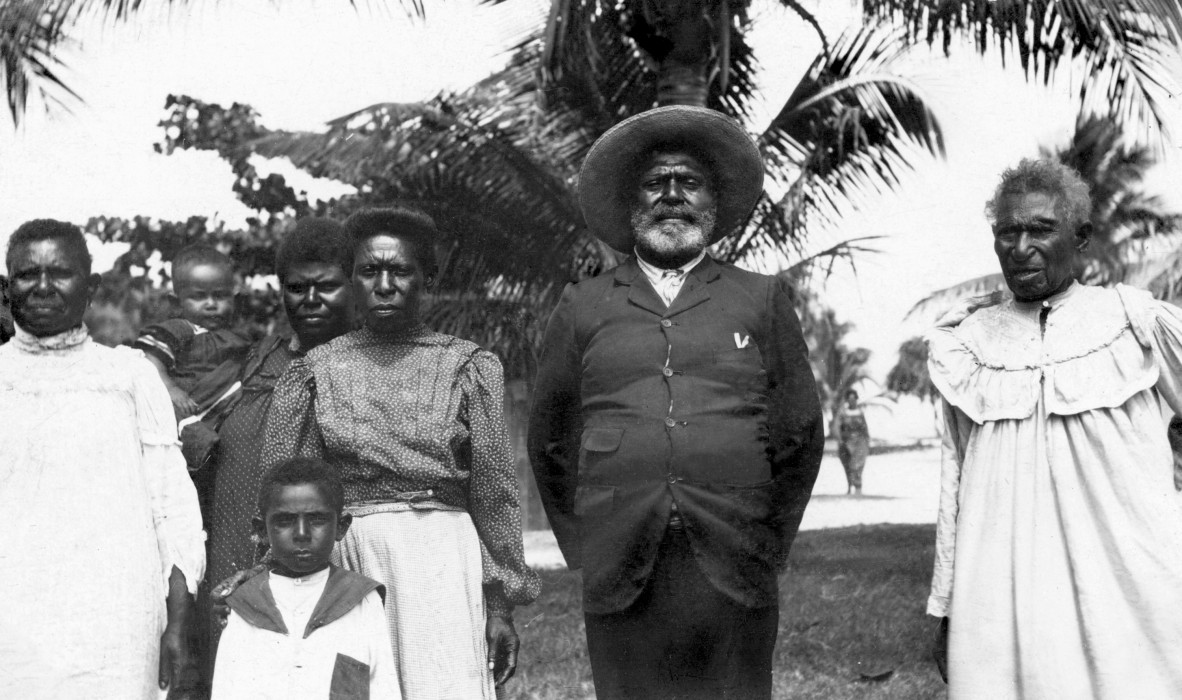

Maino Mamoose of Yam Island and his descendants, Queensland. 30020 Glass Plate Negatives of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Communities, John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland. Image number 30020-0001-0048.

Upon becoming the Mamoose, Maino very quickly adjusted to the changes occurring within the Torres Strait, focussing on the shifts in power that were happening at the time. He aligned himself with Banner, Sir William Macgregor and other officials to establish a permanent base on Yam island for the Tudu People. Maino worked through many different realms of governing, including traditional, religious, and governmental channels to provide a foundation on which the people of Tudu could continue to live prosperously.

Eventually, Maino led his community to establish and relocate to a village on the north-western side of the island of Yam, due to widespread erosion of Tudu and more reliable sources of water on Yam. He quickly made improvements on the island, planting over 3,000 coconut trees in plantations on Yam and other nearby islands traditionally controlled by Kebisu.

Maino of Yam Island, Torres Strait Queensland, ca. 1925. John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland. Negative number 55673.

Maino was well documented to be a great leader, statesman, and storyteller. The former Protector of Aborigines, Cornelius O’Leary, named Maino as an able Administrator and one of the most outstanding men he had ever known. In the Queensland Protectors report of 1909, Maino is noted as “possessing a judicial mind and just discriminations that would win the respect in courts higher than our own.” In an article in The Queenslander from 1925, C. Coral describes an evening when Maino tells yarns of “ghost stories” and his expeditions in the early days to gathered government officials long into the night.

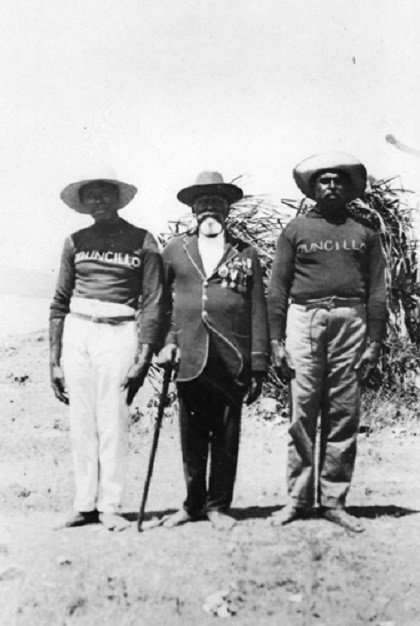

Three men from the Torres Strait. Left to right: Billy Bann, Maino, Kebish. John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland. Negative number 118676.

In fact, many of Maino’s yarns were captured in various newspaper articles of the day, recorded by Maino’s guests while sitting in his grass-thatched house on Yam. Here, he told tales of his life and the history of his culture, the years he spent with Sir William Macgregor in the early days of Papua, confrontations with the bushmen of New Guinea, reminiscences of the early Torres Strait days, stories of shipwrecks and the tragedies he knew first hand.

Maino died in 1939, believed to be around 80 years of age. The great leader, who never appeared before visitors unless his breast was fully decorated with medals and ornaments, was buried in an elaborate traditional ceremony at his home in Yam. Many government officials, including O’leary, were present to pay their respects to the last great Mamoose of Yam island.

Maino and family at Yam Island, 20 July 1911. Queensland State Archives, Item Representation ID DR5856, Item ID ITM1443446.

Before he died, Maino traded and donated many artefacts to the anthropologist Alfred Cort Haddon. Many of these amazing items are now housed in the British museum, which you can see here. While these items are digitised and preserved well, Many may question the validity of the British museum’s ownership over the artefacts. On the road to reconciliation, it is important that collecting institutions around the world recognise the cultures and communities that have a right to their traditions, histories, and culture.

The life of Maino and the history of Yam and Tudu island is rich, varied, and deserves more research. Click the links below to read more from the newspaper articles refering to Maino:

- Stories of the Strait – Maino’s Memories By C. Coral (1928, February 9).

- THE SKETCHER. When Shadow Lengthen. Yarns of Old Identities of Torres Strait. By C. Coral – Maino and the Warriors of Tutu, 1925, June 6

- THE SKETCHER. When Shadow Lengthen. Yarns of Old Identities of Torres Strait. By C. Coral – Maino and the Warriors of Tutu (Continued from June 6) (1925, June 20)

- GOSSIP. Dinkum Abo. King (1939, December 23).

- AUSTRALIANA. His Majesty Maino “The World's News” 29 July 1939

- Characters of Thursday Island, 193, February 27

- Wild and Wide. Maino’s Majesty 1937, November 13

- Maino artefacts at the British Museum

- Idriess, Ion L. Drums of Mer / by Ion L. Idriess. (1936) Australian Angus & Robertson Limited – Sydney

Digital link to records: http://onesearch.slq.qld.gov.au/permalink/f/13urfr2/slq_alma2110887894000206

This material contains Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander content, and has been made available in accordance with State Library of Queensland’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Collections Commitments.

Comments

Your email address will not be published.

We welcome relevant, respectful comments.