I introduced my last post with a quote attributed to the French statesman Talleyrand, who served French governments, before, during and after the French revolution:

He who has not lived in the years before the revolution cannot know what the sweetness of living is.

anti-revolutionaryI keep returning to Talleyrand’s remark because it resonates with me, even though I’m not sure what it really means; partly because I’m not sure what it means. Certainly it refuses easy interpretation or the sort of casual dismissal which nostalgia usually elicits. It intimates a story, a long story, with many twists and turns, a story that needs to be taken in and thought about deeply before rushing to conclusions.

My last post argued that nostalgia comes in two forms, one reactionary, intrinsically hostile to anything new, but the other creative because it’s about picking up a lost thread. It concluded that the tragedy repeated over and over again in the face of structural change is that the two forms of nostalgia are confused with each other, or not distinguished apart, so that any form of nostalgia comes to be seen as impeding adaptation to change.

In response to one of my posts about the relationship between the promise and practice of libraries becoming ambiguous and strained a well-meaning colleague sent me an aphorism attributed to Socrates:

The secret of change is to focus all of your energy, not on fighting the old, but on building the new.

Socrates, Circa 470 BC - 399 BC

Not knowing what to make of it I sent it to a friend who shot me back this passage from Anna Karenina:

"But you say it's an institution that's served its time."

"That it may be, but still it ought to be treated a little more respectfully. Snetkov, now...We may be of use, or we may not, but we're the growth of a thousand years. If we're laying out a garden, planning one before the house, you know, and there you've a tree that's stood for centuries in the very spot.... Old and gnarled it may be, and yet you don't cut down the old fellow to make room for the flowerbeds, but lay out your beds so as to take advantage of the tree. You won't grow him again in a year”.

The feelings I’m talking about are wretched and depleting; opaque and resistant to consolation. Observing my friend’s startling recourse to Tolstoy it occurred to me that escaping their grip might be helped by interrogating whatever arouses them – Socrates’ aphorism for instance.

In an optimistic frame of mind you can construe Socrates’ aphorism as pro tree, in Tolstoy’s sense. It would be wishful thinking to read it as sympathetic to the sort of reconciliation with the past advocated in Tolstoy's book, but it can be read as acknowledging that a preoccupation with fighting ‘the old’ – old values and priorities – may be at the expense of ‘building the new’. This interpretation depends on assuming that for Socrates ‘change’ and ‘building the new’ are synonymous; that all he’s saying is that the secret of building the new is to focus all of your energy on building the new, not on fighting the old.

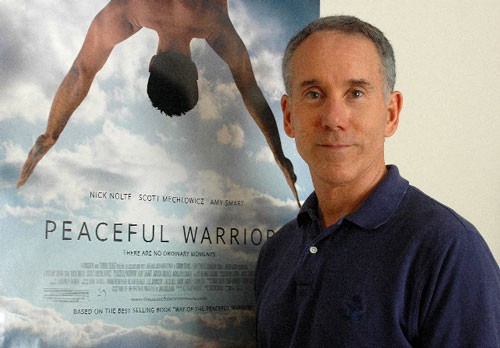

The nervous ambivalence about the past which Socrates’ aphorism conveys is characteristically modern, quite absent in classical thought, which made me wonder about its provenance. I Googled it and found it has spread far and wide, cited frequently in popular self help forums but also appearing here and there in more serious, sober settings. A lot of the time, even in the more serious, sober settings it's attributed to the old Greek guy, but sometimes it’s acknowledged as emanating from a latter day, American Socrates, a sage petrol station attendant in a fictionalised memoir by the champion gymnast, Dan Millman, Way of the Peaceful Warrior: A Book that Changes Lives, first published in 1980. An international bestseller, the book was made into a movie, starring Nick Nolte as Socrates.

Several editions of Way of the Peaceful Warrior have now been published. From what I can tell the version quoted here first appeared in the 1984 edition:

Back in the office, Socrates drew some water from the spring water dispenser and put on the evening’s tea specialty, rose hips, as he continued. “You have many habits that weaken you. The secret of change is to focus all your energy not on fighting the old, but on building the new.”

It’s notable, I think, that Socrates stopped short of equating ‘weakening habits’ and ‘the old’, allowing the possibility that treating them both as the same thing is mistaken, that what we are sometimes quick to identify as ‘weakening’ - inherited values and priorities, - may not be all that weakening after all and may even be part of the solution to whatever uncertainty we’re encountering. But I must not speak for Socrates.

What Socrates said changed subtly but significantly between editions of Dan Millman’s book. In the 2006 edition, a little over twenty years after the version sent to me the door seems to have firmly closed on a Tolstoyan reading of what Socrates has to say about change. ‘Weakening habits’ have become ‘old patterns’ and there now can be no doubt that for Socrates ‘building the new’ is only a means to a greater end – ridding oneself of 'old patterns':

Back in the office, Socrates drew some water from the springwater dispenser and put on the evening’s tea specialty, rose hips, as he continued. To rid yourself of old patterns, focus all your energy not on struggling with the old, but on building the new.

Anna Karenina“But you can’t just swat it away; that’s why it warrants such attention.” I stopped abruptly, realising I was talking in circles.

“Because … because … who am I to think differently to Socrates?”, I blurted out desperately.

“Then you must talk to Socrates”, my friend replied, ever so gravely.

Sometimes, Socrates, something happens in the world and a gap suddenly opens up between a cherished promise and received ways of fulfilling it, a wild treacherous sea gap, creating enormous uncertainty. Sometimes the change is so profound and the gap so wide that it’s not at all clear how to get to the other side. Something like this has happened in libraries over the last twenty years.

I’ve suggested that either of two types of nostalgia is one response to the great cleaving away of the present from the past. Another response – what I’ve called anti nostalgia - is to look for the cause of the gap within ourselves, weakening habits that must be overcome. But sea gaps never arise within ourselves; they’re out there – in the sea; they have to be sailed across in real boats through real storms, calling on whatever wisdom and courage we’ve held on to.

The 1984 version of Socrates’ aphorism registers 38,700 hits on Google, compared with 326 for the 2006 version. Clearly it’s been a source of hope and inspiration for many people, when the version of about twenty years later has not. In trying to fathom a familiar sense of beleaguerment I’ve ended up complaining that Socrates seems fixated on weakness, on how people need to change and not the world, but that can’t be said of the popular version of his aphorism originally sent to me, which makes no mention of weakness. That must be its appeal – that it’s on the side of vitality , whatever its wellsprings.

Dan Millman, standing in front of a poster advertising the film adaptation of his bestseller, Way of the Peaceful Warrior: A Book that Changes Lives

Why then the feeling of beleaguerment, the reflexive defence of a cherished legacy, the exhaustive interrogation of a well-meaning aphorism? Oh what a state we can get into, peering across the daunting gap between the promise of libraries and its fulfilment, craving the secret of change, but also agitated by secrets that are not recognisably about the crossing or reveal no more than what we already knew – that there’s a gap to be crossed. It falls to the many, mostly silent, voices in libraries, acutely conscious of the gap, to start doing the hard work of articulating exactly what the gap is and how libraries need to change to get across it. Perhaps Socrates' main point is that feeling beleaguered - waiting and waiting for someone to tell you what you want to say - won’t get you across the gap. The secret of change really is to focus all your energy on building the new.

Comments

Your email address will not be published.

We welcome relevant, respectful comments.