From Jungle to Desert: The Joe Cazey Post-Vietnam Story

By Ethan Devereux-Phillips, Engagement Officer, Anzac Square Memorial Galleries | 11 March 2025

The steaming jungles of New Guinea, the bustling streets of Singapore and the dusty hills of Beersheeba – what do these places have in common? Many will quickly recognise them as sites of Australian military legend, where the tide of battle turned either against us or in our favour. Places that are inscribed on our memorials and recalled every Anzac Day. However, they share another connection. Each was visited by Sapper Joe Cazey during his service.

Joe is amongst tens of thousands of Australians who have seen overseas service as part of their career in the post-World War II period. His first overseas deployment was in Vietnam, where he was involved in laying a minefield at Nui Dat and clearing Viet Cong passages as a tunnel rat. If you’re interested in that part of Joe’s story, you can read more here. However, we will be joining Joe in Oro Province (former Northern District), Papua New Guinea with the District Engineers Office (now 19th Chief Engineer Works). Joe was posted there in January 1968, some six months after his return from Vietnam.

‘People did a two-year rotation, and we were effectively the Public Works Department for the Australian Administration looking after one district … The unit was in New Guinea from 1963 to 1996. Quite a long deployment.’

While far lusher than Mt Hermon (at about 2814m above sea level), Oro Province was similarly remote and relied on aircraft transportation.

The unit had a handful of staff, originally 23, which covered administrative and technical planning duties. A diverse array of construction work was contracted to local companies and labourers, with Joe distributing daily payments.

‘[There were] sometimes 500 labourers a day doing maintenance on roads, maintenance on buildings. Anything and everything. Like I say, we supervised the building of a hospital and that was – all the grounds, it was decided, we’d do ourselves under day labour. So, it was a very different posting.’

Another duty that fell to Joe was the disposal of remnant World War II ammunition. In one instance, Agriculture and Fisheries officials went to attend a village feast, only to find a steer spit-roasting on a Bangalore torpedo. It was quickly replaced by a star picket and Joe called to detonate it nearby.

‘We did a lot of unofficial bomb disposal because the place was just – the area we were in was heavily fought over and a lot of stuff lying around in the scrub.’

Returning to Australia in December 1969, Joe was posted back to Brisbane with several engineering units. After 1972, he was involved in a major structural overhaul which saw engineer squadrons reorganised into regiments. His mind, however, lingered on further overseas postings.

‘I’d been asking for postings in Singapore, but everyone did and it was a really one of the gun postings to get, you know. Beautiful, fairly relaxed.’

In short order, fortune smiled on Joe and, after convincing his Commanding Officer, he was posted to Singapore as part of Australia, New Zealand and United Kingdom (ANZUK) Force.

‘I was a Staff Captain in charge of accommodation and works … We were looking after, amongst other things, returning property to the Singapore Government. As units pulled out or functions changed and property became spare, it went back to the Singapore Government … It wasn’t physically hard, and it was made easier by the fact that you get picked up at home every morning in an airconditioned taxi.’

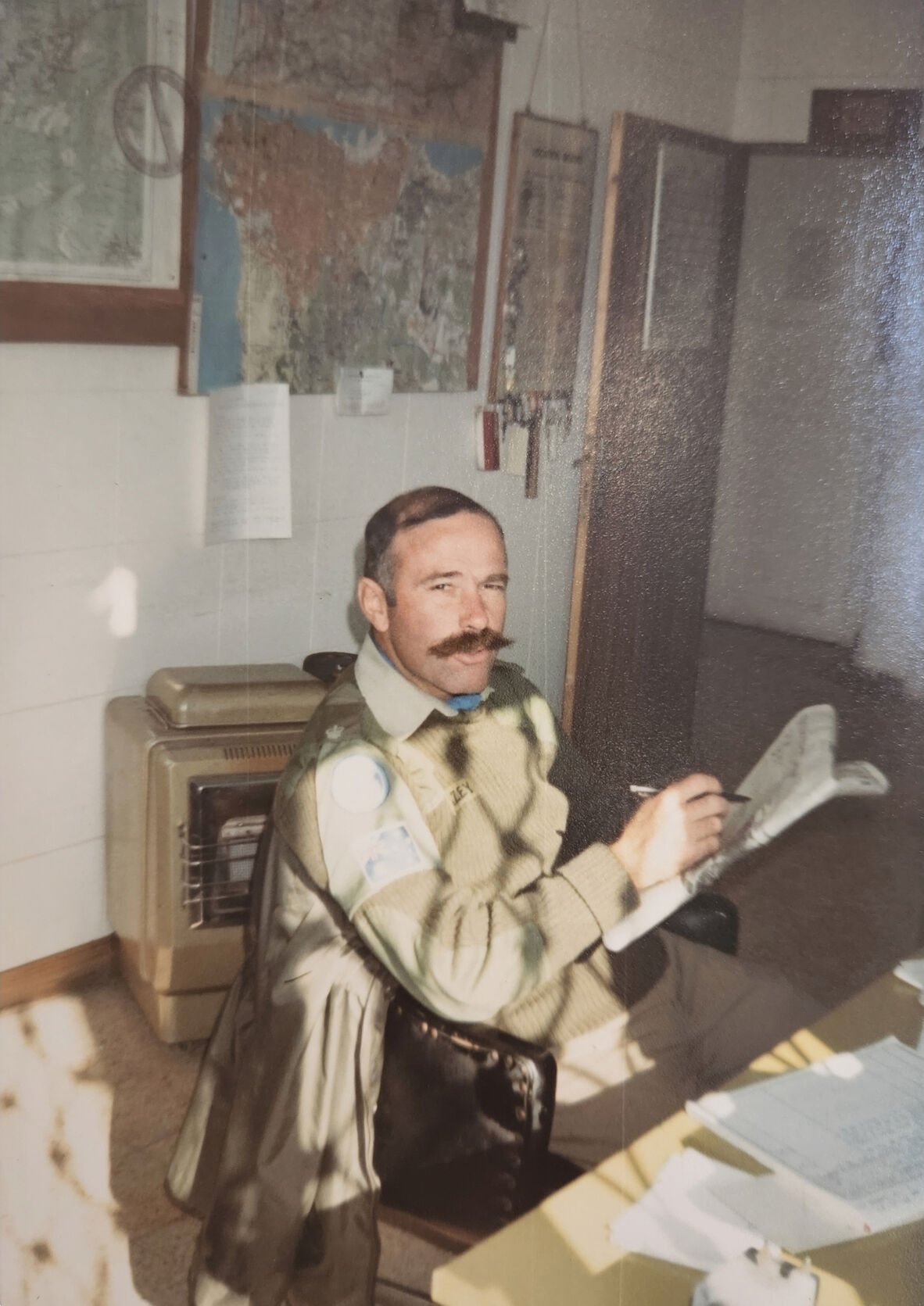

Joe at work in the office, Beirut 1984.

During the posting, which lasted from 1972-74, Joe was accommodated at Seletar (an ex-Air Force station) with his wife, who had also joined him in New Guinea. Although it was primarily an office role, Joe found – with enough charisma in the Officer’s Mess – he could arrange outings to stretch his legs.

‘I tried to con my way on to certain exercises with the 28th Field Squadron, which was the engineer unit attached to the 28th Brigade, which was the ANZUK brigade which commanded three battalions … When they went up country to do training exercises and things like that, if I could be spared, I’d con my way into going up there. Even if just a one day visit; sometimes stay out there for a couple of days with them and just catch up with people I knew in the squadron. Some of my classmates and things like that I knew from Portsea. But it wasn’t a field job, you know. I was very much an office warrior in those days for those two years. It was good experience, but it wasn’t – wasn’t career making all that much.’

Singapore was followed by a string of postings back in Australia including at Staff College, the 1st Division Engineer Headquarters and an 18-month position in Canberra. The latter posting was in an office which oversaw Defence Force aid to the civil power and aid to the civil community. These powers mandate how Defence material and personnel are deployed in emergencies, such as bushfires, floods, pandemics and terrorist attacks. Aid to the civil community also controls Defence contributions to non-emergency causes, such as commemorative events.

The Canberra office was further responsible for supervising plans for Australian overseas deployments. It was here that Joe first became involved in United Nations (UN) operations, as his office oversaw Australia’s contribution to the UN Military Observer Group in India and Pakistan (UNMOGIP), the UN Truce Supervision Organisation (UNTSO) in the Middle East and planning for the UN Transition Assistance Group (UNTAG) in Namibia. In time, an enquiry came across Joe’s desk about raising the Australian commitment with UNTSO from 10 to 14 and, after some delays, he was on a flight to Palestine to support Australia’s longest continuous military commitment.

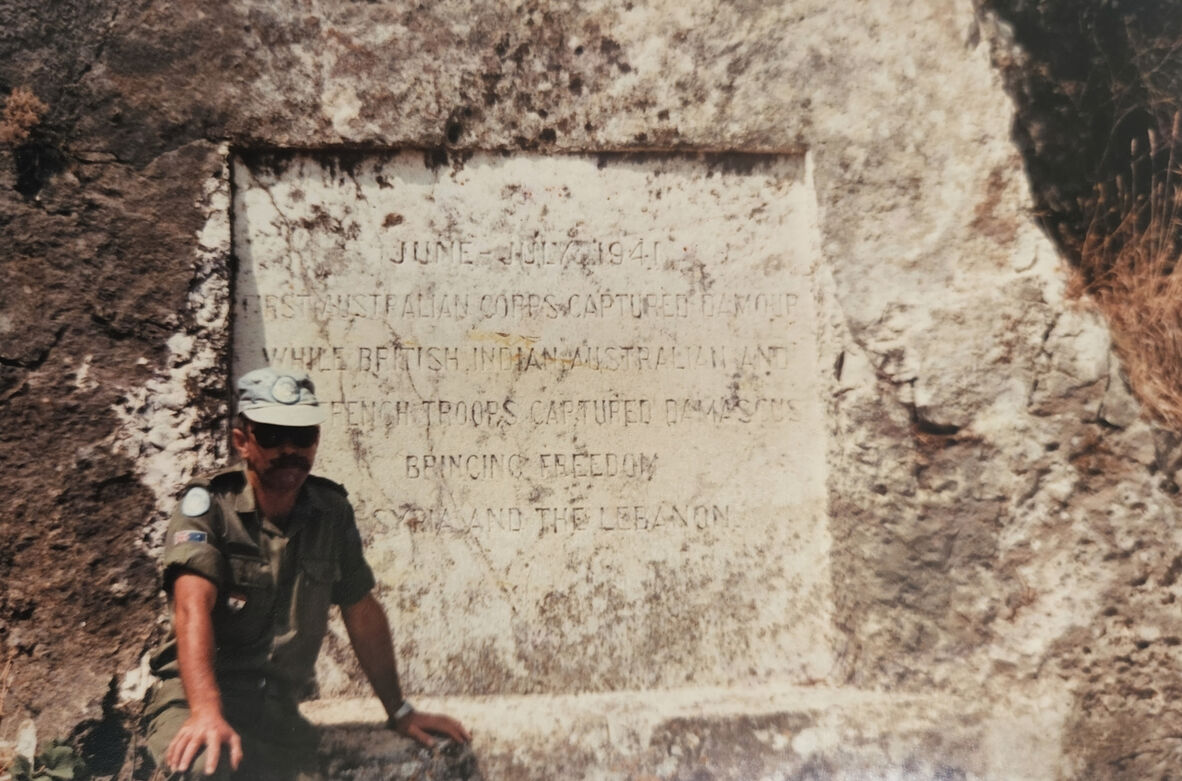

Joe Cazey beside a memorial to the Battle of Damour. The inscription reads ‘June – July 1941 First Australian Corps captured Damour while British, Indian, Australian and Free French troops captured Damascus bringing freedom to Syria and the Lebanon.’

UNTSO was the first UN peacekeeping mission, established in 1948 to monitor a truce to the Arab-Israeli war. UN Military Observers (UNMOs) are posted in 5 states: Israel, Syria, Egypt, Lebanon and Jordan. Their mandate is broadly to observe and implement truce and armistice agreements in the region, and to support associated missions such as the UN Interim Force in Lebanon (UNIFIL) and UN Disengagement Observer Force (UNDOF). In practice, this involves monitoring demilitarised zones, negotiating ceasefires between militias, facilitating dialogue between regional states, developing local relations and numerous other tasks.

Australia has contributed UNMOs, all of whom are unarmed and largely military officers, since 1956 under Operation Paladin. Most UNMOs spend 6 months in Israel and another 6 months in a surrounding Arab country, or vice versa. In Joe’s case, he was first posted to Damascus, Syria.

‘I did duty on observation posts on the Syrian side of that area of separation. You’d go out for six days with another person, all men in those days, and there were – you could never go out with your own country. You couldn’t have two Australians on a post, had to be any two from any two countries. Considering that there were nominally 17 nations in UNTSO, that wasn’t too difficult.’

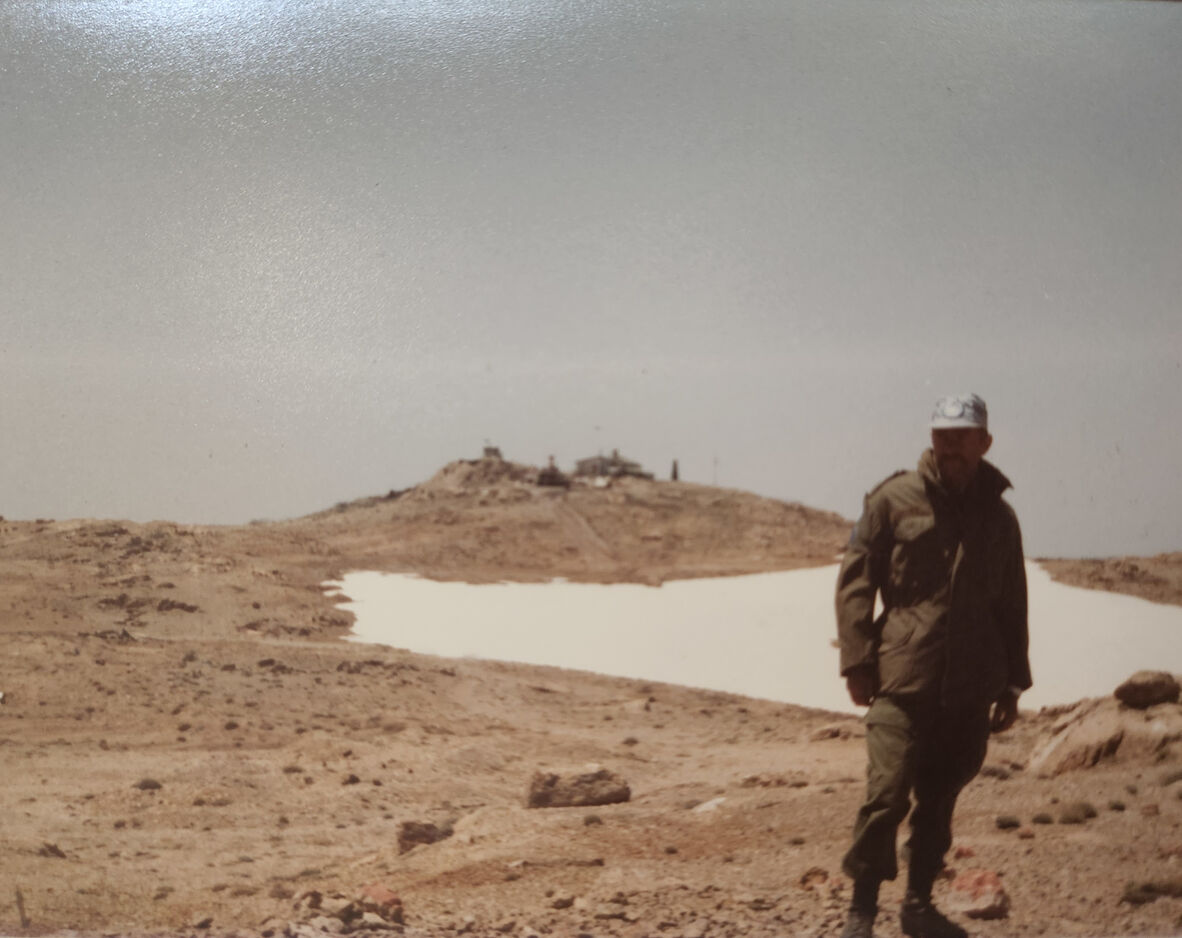

OP 72 overlooking the AOS. Note the UN signs, white paint and flag, which had to be replaced frequently due to high winds.

The Syrian observation posts (OPs) stretch along the Golan Heights. This mountainous region has been occupied by Israel since the 1967 Six-Day War, with a ceasefire ‘Purple Line’ established at the end of that conflict. Following the 1973 Yom-Kippur War, a demilitarised zone, known as the area of separation (AOS), was established along the Purple Line. UN resolution 350 was passed in 1974, creating UNDOF to oversee the AOS. Either side of the AOS, an area of limitation restricts the number of troops that can be stationed at 5-kilometre intervals.

‘UNTSO had to go on the ground and so we would conduct these inspections either side of the line, every – about 10 to 14 days, to check … And quite often you’d see very fresh tracks of armoured vehicles where armoured vehicles should not be. They’d pulled out the night before.’

Life at the OP was routine, with duties split evenly between the ‘outside’ and ‘inside’ man, who would rotate every day. The former was tasked with observing the AOS and making note of any military activity, such as a plane flyover or an exchange of fire. Meanwhile, the inside man was occupied with more domestic duties, including cooking for both men. Culinary skill became a matter of pride amongst many UNMOs, and the exchange of national dishes was a frequent tradition.

‘Incursions into the area of separation were mostly civilian because the farmers, they’d lost their land … So, quite often, through the binoculars, you’d see people from a village come in, and they’d cut through the wire fence, and they go in there to herd their sheep through and … graze their sheep inside the area of separation, which is a bit dangerous because there’s a lot of minefields. There’s a lot of unexploded ordnance. So, occasionally, you’d be, sort of, looking through the binoculars and you see a herd of sheep down there, and you look away, and all of a sudden, boom! … But also, very sad sometimes, because there was a particular village called Majdal Shams … and it was basically cut in half, and the people that were on the – what was now the area of separation – were shifted to the other side … And so, they’d be trying to communicate with their relatives and friends over – well at that point it might be over a kilometre and a half.’

Joe's caption: The third UNMO at OP 56 'Outside Cat'?

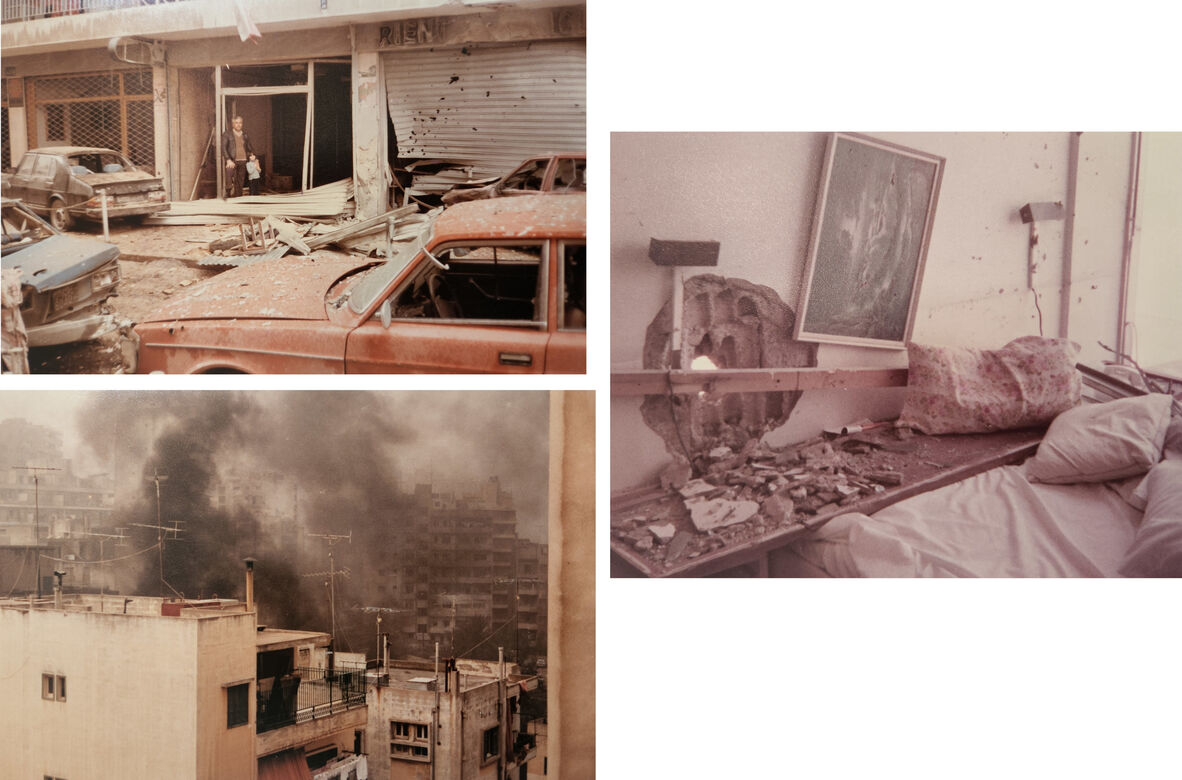

Deviating from the usual UNMO assignment, Joe spent 3 months in Syria before transitioning to Lebanon where he would spend the rest of his deployment with Observer Group Beirut. The Lebanese Civil War was ongoing, and tensions were high. In September 1982, Britain, France, Italy and the United States sent a Multinational Force (MNF) to Lebanon in response to political upheaval and the Israeli invasion earlier that year. Over 2 deployments, the MNFs goals were, broadly, to oversee the evacuation of the Palestinian Liberation Organisation from Lebanon, support Lebanese military and political stability, and prevent further massacres such as those at Sabra and Shatila; which had seen hundreds of civilians, mostly Palestinian, killed by the Lebanese Christian Phalangist Party. On 23 October 1983, 2 near simultaneous suicide truck-bombs exploded at the US and French barracks, killing 299 and wounding over 100. For the US Marines, who suffered 220 dead, it was the costliest day since the 1945 landing on Iwo Jima.

‘I was on the road going in early. I was the Operations Officer at this stage for the Observer Group Beirut and my boss was a French Foreign Legion Officer. He was on the road also. Talked to each other on the radios and he said, “Look, I’m closer to the American position, you’re closer to the French position, that’s how we’ll divide it up. Go and see what you can find out” … Now, the French were in a high-rise six storey building – French Foreign Legion battalion – and when the bomb went off at the airport, which was about two K’s away from the French position, a lot of the French guys got up, went to the balconies to see what was going on … Then the truck came in under their building and went off. The ones who were on the balconies got blown out. Most of them survived, or got injured, but not necessarily killed. The ones who stayed in bed, the building pancaked down.’

Joe himself came under fire himself on several occasions, particularly in Beirut, which was frequently shelled and fought over by militias. Beirut was divided along the ‘Green Line,’ with Christian and Muslim factions generally controlling the East and West respectively. Joe and others lived in the western half, with their headquarters in the east, and crossed the line multiple times a day. When violence flared up between militias, UNMOs risked getting caught in the crossfire.

‘[On one occasion] it took me 45 minutes to go 100 yards across the line. And when I got clear into West Beirut, just then a young teen with a rocket propelled grenade took aim to shoot across the – I was in his backblast area. I was sitting in my Passat, Volkswagen Passat, with the back end of that thing only about a metre – if he had fired it, I’d have been dead … Fortunately, one of the other militia who was there, pushed him out of the way and he didn’t have his finger on the trigger, so it didn’t go off.’

A view down the Green Line, Beirut 1983.

Coming under fire put great stress on the nerves of UNMOs. Joe worked alongside a Canadian Captain who came under nighttime artillery barrage at a service station. The following evening, the same captain was pinned down by .50 calibre fire while on patrol.

‘The next night, a single shot was fired, [indistinguishable] one of the refugee camps. This guy just lost it from the post-traumatic stress. He just fell apart. Young 25 year old infantry captain crying his eyes out. He just couldn’t handle it any longer, you know. Your heart goes out to him because – this sense of frustration that we couldn’t shoot back. It wasn’t a case of we wanted to shoot back but the fact that he couldn’t [indistinguishable]. In some respects, I was far more comfortable in Vietnam, where I had a weapon in my hand and I could shoot back if I had to [indistinguishable] whereas here you felt really, really vulnerable.’

To date, one Australian (Captain Peter McCarthy) has been killed over the course of Operation Paladin, while numerous others have been injured either physically or psychologically. Joe himself has suffered with PTSD as a result his UNTSO deployment.

‘UNTSO is not considered to be war service. No matter how serious some of the spikes are, overall it’s considered to be a relatively peaceful involvement in the many, many years that people have been involved … We should recognise that it’s not the conflict itself, but it’s the incidents that make up the conflict that are the things that do all the damage … If we send people overseas, we’ve got to support them when they come back because they’re damaged goods.’

The aftermath of shelling at Joe's hotel accommodation. Note the hole in the wall of Joe's apartment.

Despite the difficulties of the deployment, Joe found it offered many opportunities too. The multinational force allowed him to meet and work alongside skilled people from varied backgrounds, including Soviet officers. There were also some travel opportunities, such as a trip to Beersheba to commemorate Anzac Day.

Joe was impressed by the resilience of many of the people he met. On one occasion he was shopping for shoes in Beirut when an artillery barrage landed nearby. The store owners calmly took him and another UNMO to the basement and offered them tea. Once it was clear, they continued the transaction like normal, despite the freshly broken windows.

‘We’d go into a refugee camp like Bourj el-Barajneh or Sabra Shatila, and they’re as poor as church mice, and they’d be offering you tea and coffee and stuff, you know. And there’s nothing we could do to help them. We’re just there to be the eyes and ears of the world.’

UNMOs at Beersheba War Cemetery on Anzac Day. Left to right, top: Warren Hind, Pierre Gregor, Mark McGowan, Mark Whysnowski, Peter Keane, Neil Garnet. Bottom: Joe Cazey, Keith Hall, Ron Elnis, Bob Gianatti, Bob Helm, Dougall McMillan.

A member of the Israeli Defence Force who attended the Anzac Day ceremony. They have been tagged by Australian Army stickers ‘not provided by our people.’

After his year in the Middle East, Joe returned to staff roles in Australia. At the time, officers were required to retire when they reached a certain age, and for Joe, as a Major, this was 42. His transition out of Defence went smoothly, first overseeing the administration of St Leo’s College at the University of Queensland for 3 years before transitioning to a skill training not-for-profit.

Now retired, Joe continues to serve his communities, both civilian and defence. He has been involved with Scouts Australia for many years and usually attends the Brisbane Anzac Day Dawn Service with his troop. He also volunteers time with Mates4Mates, supporting fellow veterans and their families. Through these organisations, State Library of Queensland and others, Joe is outspoken about his experiences to educate on the realities of service life.

‘It’s not a case of I think I’ve got anything that’s unusual that other people don’t have as well, it’s just that a lot of people aren’t comfortable talking about it.’

Joe’s time in New Guinea, Singapore and the Middle East was not spent charging with the Light Horse or defending against the advance of Imperial Japan. It was spent in command of international groups, on routine patrols and fulfilling administrative duties. At times this work was relaxing and at others highly confronting. It is the sort of service necessary for Australia to support regional neighbours, work alongside our allies and uphold our commitments to peace. Australia and Australians rely on people like Joe Cazey to do this work on our behalf. To honour their service, we can seek to better our understanding of their experiences, the realities they face, and the hardships this can entail.

‘Somewhere in the back of my brain there’s this idea that people need to know stuff about – it’s not that I’m exceptional, it’s far from it. But the more people who are prepared to talk about their service life, the better the community understand.’

References and further reading:

Australian Peacekeeper and Peacemaker Veterans’ Association (2025) List of Missions and Operations, Australian Peacekeeper and Peacemaker Veterans’ Association Website, accessed 4 February 2025.

Australian War Memorial (2025) Battle of Damour, Australian War Memorial Website, accessed 18 February 2025.

Defense Intelligence Agency Public Affairs (2013) They Came in Peace, Defense Intelligence Agency Website, accessed 4 February 2025.

Department of Veterans’ Affairs (n.d.) S 2 United Nations Truce Supervision Organisation (UNTSO), Department of Veterans’ Affairs Website, accessed 4 February 2024.

Dixon I (2021) Tunnel Rats and Flame Throwers: The Joe Cazey Vietnam War Digital Story and Oral History, State Library of Queensland Website, accessed 4 February 2025.

Frank B (1987) U.S. Marines in Lebanon 1982-1984, History and Museums Division Headquarters, U.S. Marine Corps, Washington D.C.

Londey P (2021) ‘Fifty Year’s Watch’, Wartime Magazine, 35.

Naval History and Heritage Command (2023) Lebanon—They Came in Peace, Naval History and Heritage Command website, accessed 3 February 2025.

Nelson R (1984) ‘Multinational Peacekeeping in the Middle East and the United Nations Model’, International Affairs, 61(1):67-89.

Rabinovich I (1998) The Brink of Peace, Princeton University Press.

Ryan E (2023) 60 years and still building on capacity, Defence Website, accessed 4 February 2025.

Thomson G (1975) ‘Stability and Security in the Region after ANZUK’, Southeast Asian Affairs, 151-159.

Travers E (2025) What’s UNDOF? Why UN peacekeepers patrol the Israel-Syria border, United Nations Website, accessed 4 February 2025.

United Nations (1974) Resolution 350, United Nations Website, accessed 6 February 2025.

United Nations (1982) Report of The Secretary-General In Pursuance Of Security Council Resolution 520, United Nations Website, accessed 4 February 2025.

UNTSO (2025) Background, UNTSO Website, accessed 4 February 2025.

UNTSO (2025) UNTSO Operations, UNTSO Website, accessed 4 February 2025.

White M (2005) ‘The Executive and the Military’, UNSW Law Journal, 28(2):438-457.

Comments

Your email address will not be published.

We welcome relevant, respectful comments.