The Islands: Moreton Bay’s places of detention and separation

By Christina Ealing-Godbold, Research Librarian, Information and Client Services | 22 November 2024

Brisbane beckons through the doorway of a remaining cell block at St Helena, 2024. Image by Christina Ealing-Godbold.

Whether it was for the purposes of quarantine, imprisonment, or care of the infirm or diseased, the islands of Moreton Bay played a significant role in the history of Queensland. The islands of this complex waterway number around 360 and include Moreton Island, Stradbroke Island and Bribie Island as well as Peel, St Helena, Coochiemudlo, Garden, Russell, Macleay, Lamb and Karragarra Islands to name just a few.

Moreton Bay was the primary waterway to allow access to the Brisbane River. It was critical that ships could anchor in Moreton Bay to enable goods and people to be unloaded. The “Brisbane Roads”, as it was referred to in newspapers of the day, was an anchorage area at the end of the river that allowed large immigrant ships to wait until they were cleared to land passengers and goods. Passengers who had disease of any kind, such as typhoid, were placed in quarantine. The quarantine station was in various locations in Moreton Bay during the 19th century.

Moreton Bay’s waters were known for challenging shipping channels, and the need for lighthouses, a pilot station and a port light became evident very early in the development of the Queensland colony. The sailing instructions for Moreton Bay implored captains not to attempt going into Brisbane without a pilot. Anchorage points (known as roads) were available on the western side of Moreton Island (Yule Roads and Tangalooma Roads) as well as close to the entrance of the Brisbane River, north of Mud Island. Luggage Point was named for the spot where ships’ cargo was unloaded. “Brisbane Roads” was drawn on admiralty maps as north-east of the river mouth, out in the channel and in line with the southern end of Bramble Bay. The islands of the bay vary in size but are mostly surrounded by mangroves that make access difficult, and sharks infest the waterways. Given many British immigrants could not swim (and especially not in challenging conditions), the islands became a way of separating and detaining those considered to be problematic or requiring care in the new developing colony of Queensland.

Queensland society was a microcosm of British 19th century beliefs and ideals. It was a world where those with problems, either medical, social or behavioural, were institutionalised and separated from society. In this context, the separation was considered not only best for the developing community, but also appropriate treatment and support for the inmates or residents themselves – protecting them from harm. The close proximity to the Brisbane River mouth of a range of different sized islands separated by deep water and the threat of sharks, served as an effective, yet extremely harsh, way of detaining those who were unable to play an active role in Queensland society.

Today, the islands are valued for their environmental features, including bird and marine life, for their valued role in the lives of the First Nations inhabitants of the Moreton Bay region, and for their historic role in the development of the Queensland colony. North Stradbroke Island (Minjerribah), St Helena Island (Noogoon) and Peel Island (Teerk Roo Ra) have all been declared National Parks and Conservation areas.

Robert Dixon’s map of Moreton Bay in 1842 shows the array of islands.

Map of Moreton Bay, compiled from authentic surveys and containing all the latest discoveries made by exploring parties, 1842 by Robert Dixon. John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland.

North Stradbroke Island (Minjerribah)

Dunwich Quarantine Station

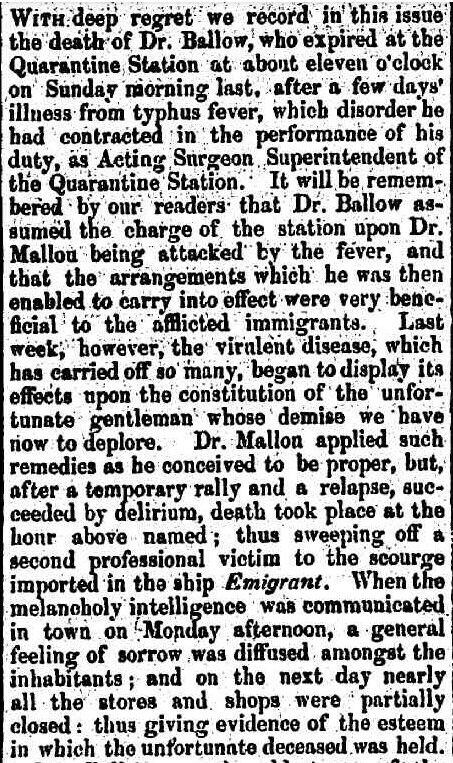

In 1849, the Colonial Secretary requested that a quarantine station be set up in Moreton Bay to process the large number of expected immigrants to the new town of Brisbane. Just a decade before, Brisbane had been a convict prison, but now free settlers were arriving to make a new prosperous life. However, immigrant ships carried many diseases that could cause significant problems for the new free colony, including typhus, cholera, leprosy and tuberculosis. The decision to locate the quarantine station at North Stradbroke Island suited the shipping channels into the Brisbane River, allowing the Government Medical Inspector to travel downriver, board the ship and indicate which immigrants needed to be quarantined. Those who showed no sign of disease could then be taken safely by smaller ship to the immigration depot in Brisbane. Dunwich was gazetted as a quarantine area in July 1850. Just after this decision, the ship SS Emigrant arrived with typhus on board, resulting in the deaths of more than 50 people, including the Queensland Surgeon-General, Dr Keith Ballow, who had tended to the sick immigrants. The ship’s doctor, George Mitchell, also died. In 1867, the quarantine station was transferred to nearby Peel Island.

Dunwich Benevolent Asylum

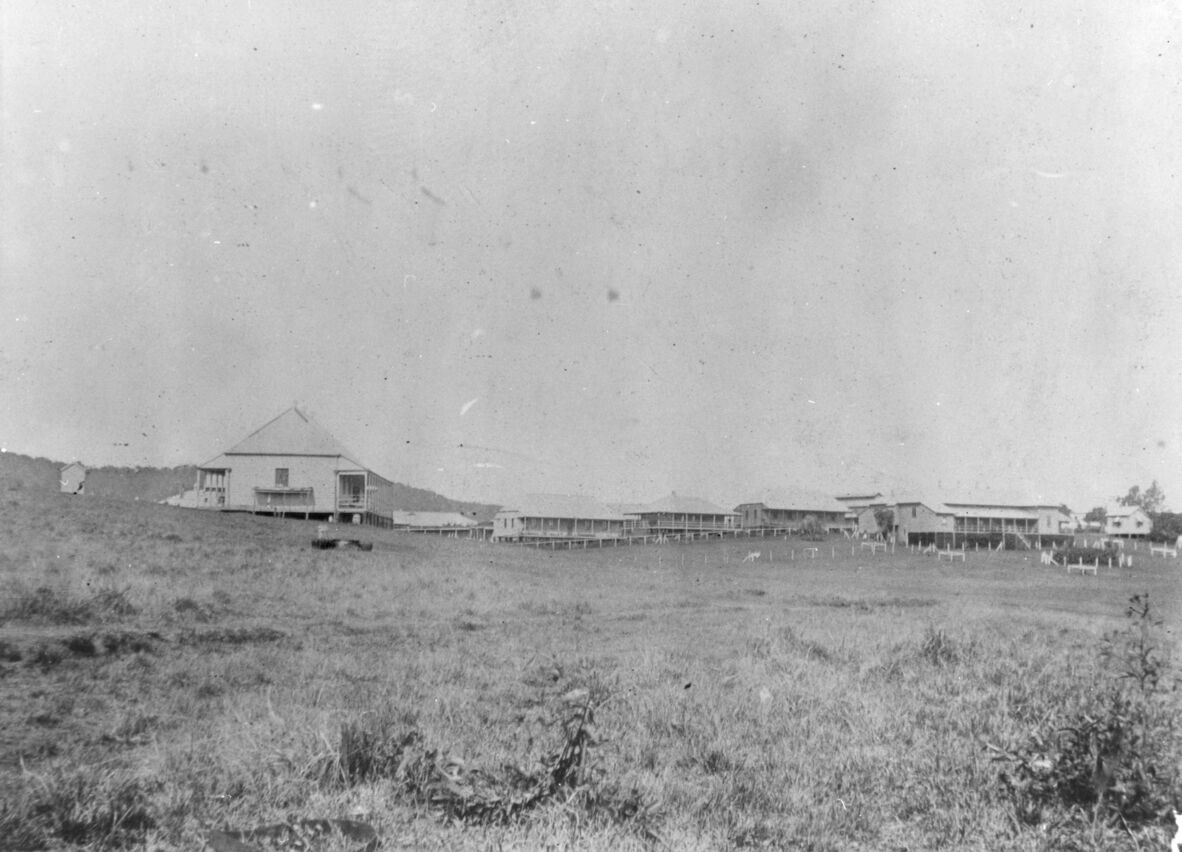

With the quarantine station moved to a smaller island, the buildings of Dunwich were now available for another purpose – that of providing accommodation for the infirm, the elderly, inebriates and those who had no visible means of support. It was a public aged care facility. Queensland had attracted many male immigrants looking for a better life, and not all found wives in a land that had many more men than women. This left many labourers without families to care for them as they aged.

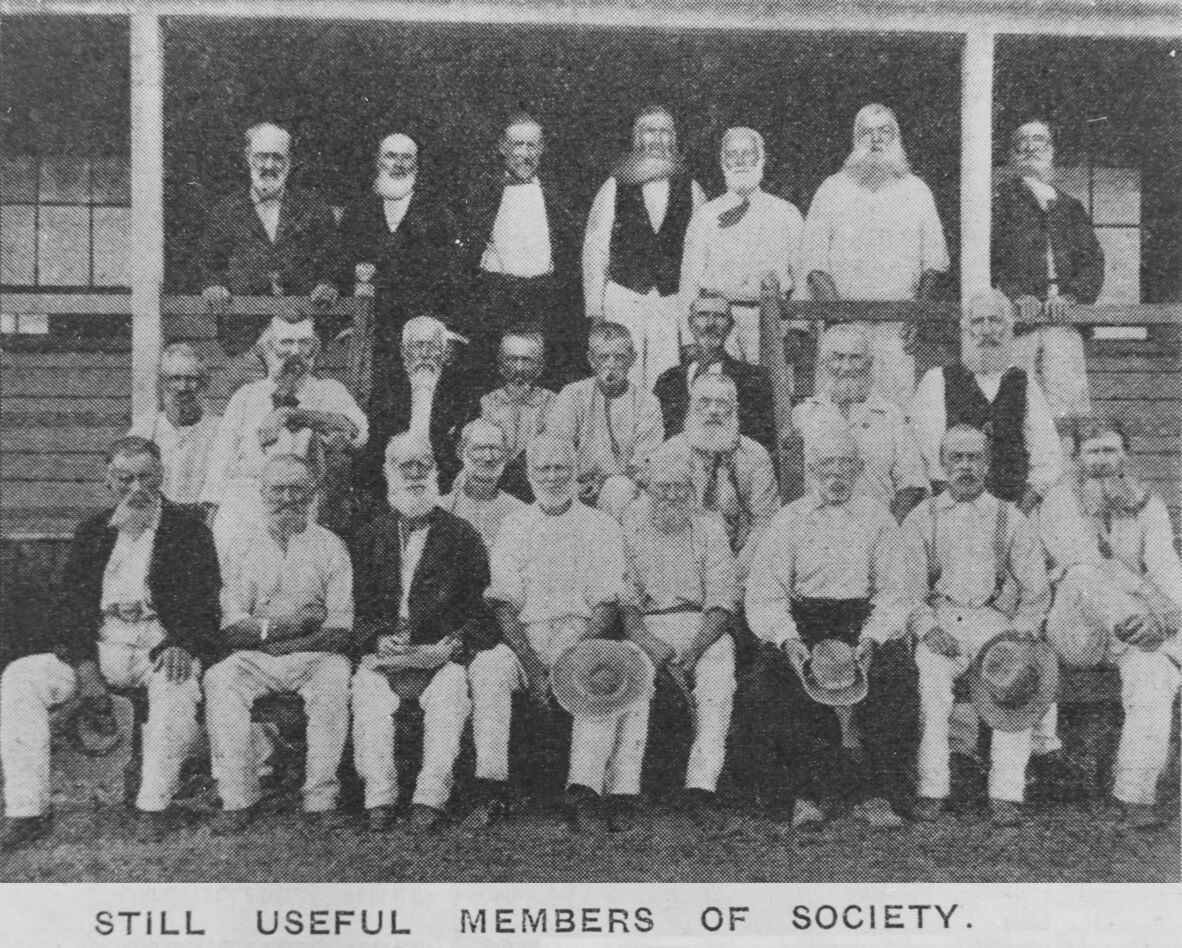

It is an interesting comment on the society of the Victorian era that anyone who was not productive and useful to society should be kept separate and institutionalised. From 1864, the new colony had many citizens asking for a place to keep these people. Once the asylum was established, its residents had very little contact with the outside world. The Queensland Government Steamer, SS Otter, serviced the asylum twice weekly from Queens Wharf in Brisbane, and family were allowed to catch the ferry down to visit once a month. However, many single men living at the asylum either had no family or had lost family due to divorce, separation, desertion, prison sentences or inebriation. Sadly, some residents were just ill and were housed at the Benevolent Asylum because they had no one to care for them. How bereft the inmate must have felt as the SS Otter returned to Brisbane at the end of the day.

Dunwich Benevolent Asylum, Queensland. John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland, Negative number: 23926.

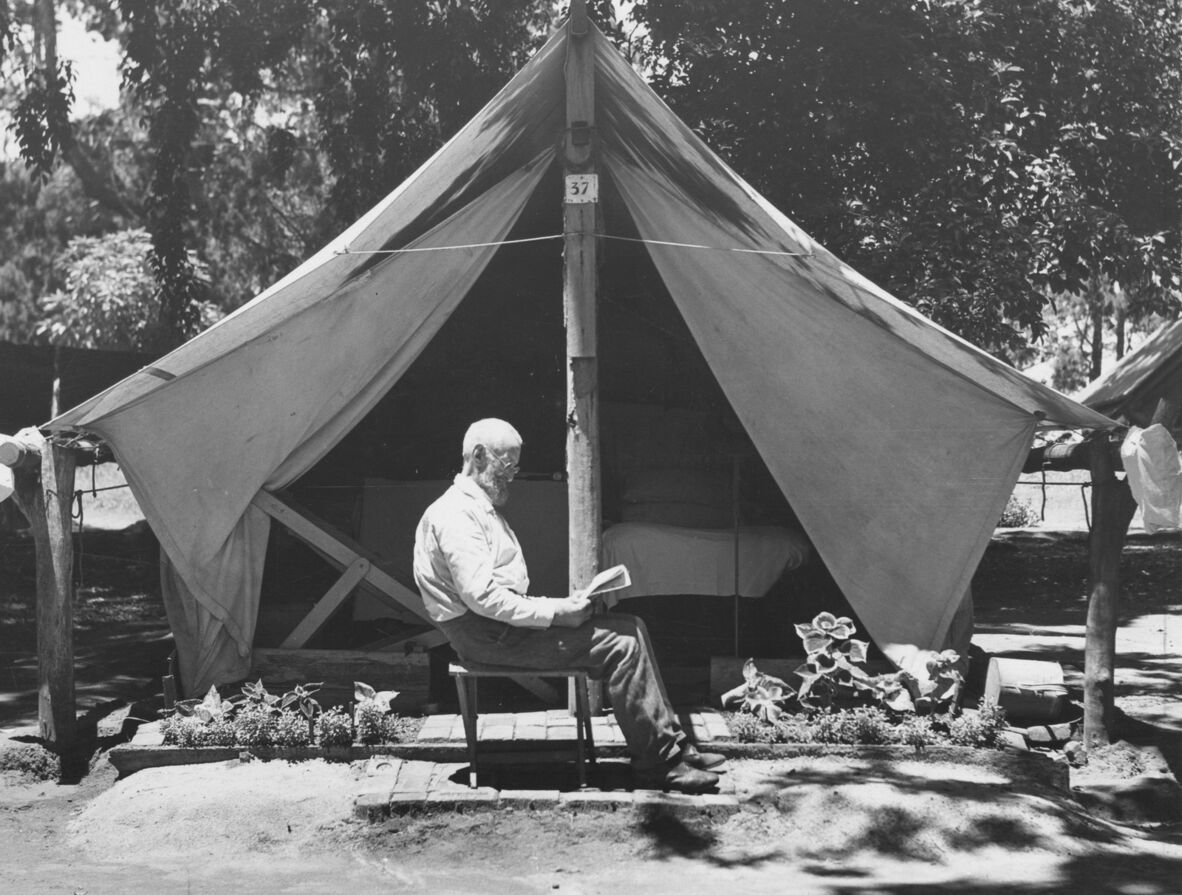

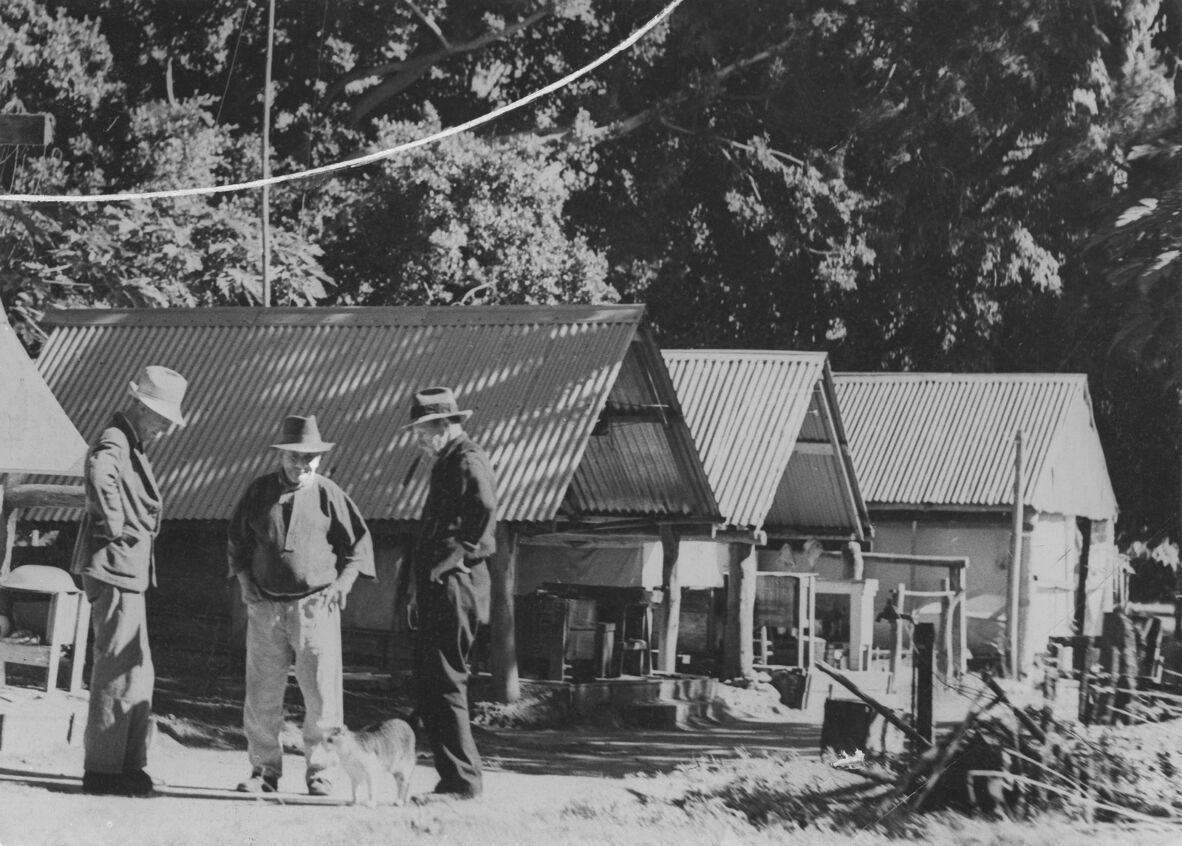

Many of the wards at the asylum were outdoors. Some inmates were housed in tents as the facility became busier and more people were sent to Dunwich. Those with tuberculosis (consumption) were housed separately.

Resident of Dunwich Benevolent Asylum, Stradbroke Island, 1938. John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland, Negative number: 62916

Dunwich Benevolent Asylum, North Stradbroke Island, ca. 1935. John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland, Negative number: 67676

Patients at the Dunwich Benevolent Institution, 1905. The Queenslander, 25 February 1905, p 17. John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland, Negative number: 20624.

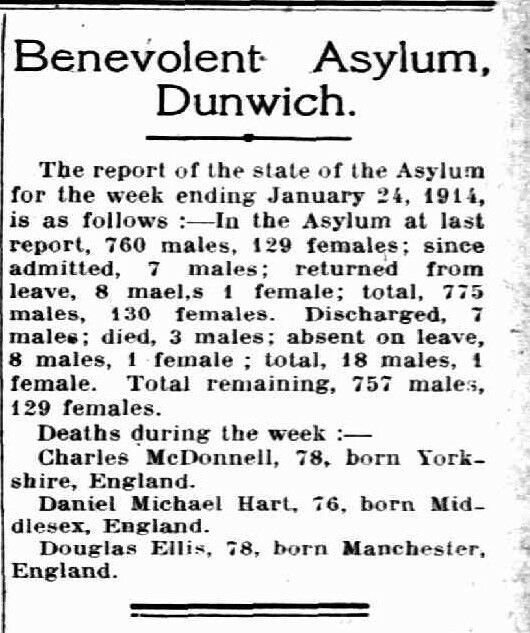

Dunwich deaths were recorded in the newspapers of the day, with names, ages and place of birth. Most were single men from Britain. In 1914, the asylum had more than 700 male residents and 129 females.

Newspapers are a vital resource for finding inmates of “The Islands”. Records for the Dunwich Asylum are kept by Queensland State Archives (some are restricted depending on date). The Queensland Government Open Data Portal also has an index to inmates up until 1927: Index to Dunwich Benevolent Asylum 1859-1927

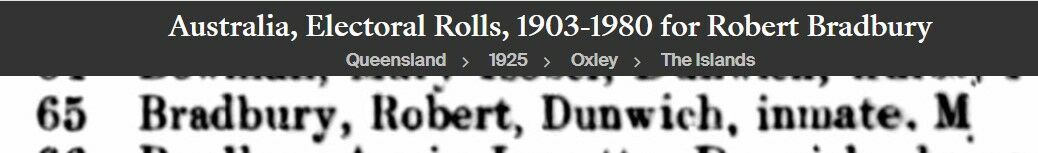

If a researcher is looking for an itinerant labourer or shearer who simply disappeared, Dunwich records are an ideal place to search. Electoral roll entries simply listed the location as “Oxley - The Islands” and their status as “inmate”. Robert Bradbury, a labourer from Cheshire, arrived in Queensland in 1888 with his brother, John Henry. John married but Robert did not. When Robert contracted kidney disease, his brother and sister-in- law cared for him until they were not able to do so anymore. In his case, his time at Dunwich (1925-1927) was for palliative care, and he died within 18 months of arrival. His family took the government steamer to Dunwich once a month to visit Robert. He is buried at Dunwich in an unmarked grave.

Australia, Electoral Rolls, 1903-1980. AncestryLibrary.com.au

Births Deaths Marriages Queensland does not show a place of death for Robert Bradbury other than “B” for Brisbane. Without the electoral roll information, the fact that he was a resident at Dunwich would be difficult to uncover.

Illustrated front cover from The Queenslander, November 24, 1927. John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland, Image number: 702692-19271124-s001

SS Otter, Moreton Bay, 1946. John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland, Negative number: 17281.

After World War Two, the buildings of the Dunwich Asylum were in need of repair. Repairs were also needed for the SS Otter, the government ship that provided access to the islands. The previously occupied RAAF station at Brighton, near Sandgate, was considered an ideal location for the Benevolent Asylum, and the Eventide Aged Care Facility was opened in 1947. Dunwich Asylum therefore ended its reign of 80 years (1867 to 1947) as a location for those who needed care due to infirmity, disease or misfortune.

St Helena Island (Noogoon)

The Colonial Prison

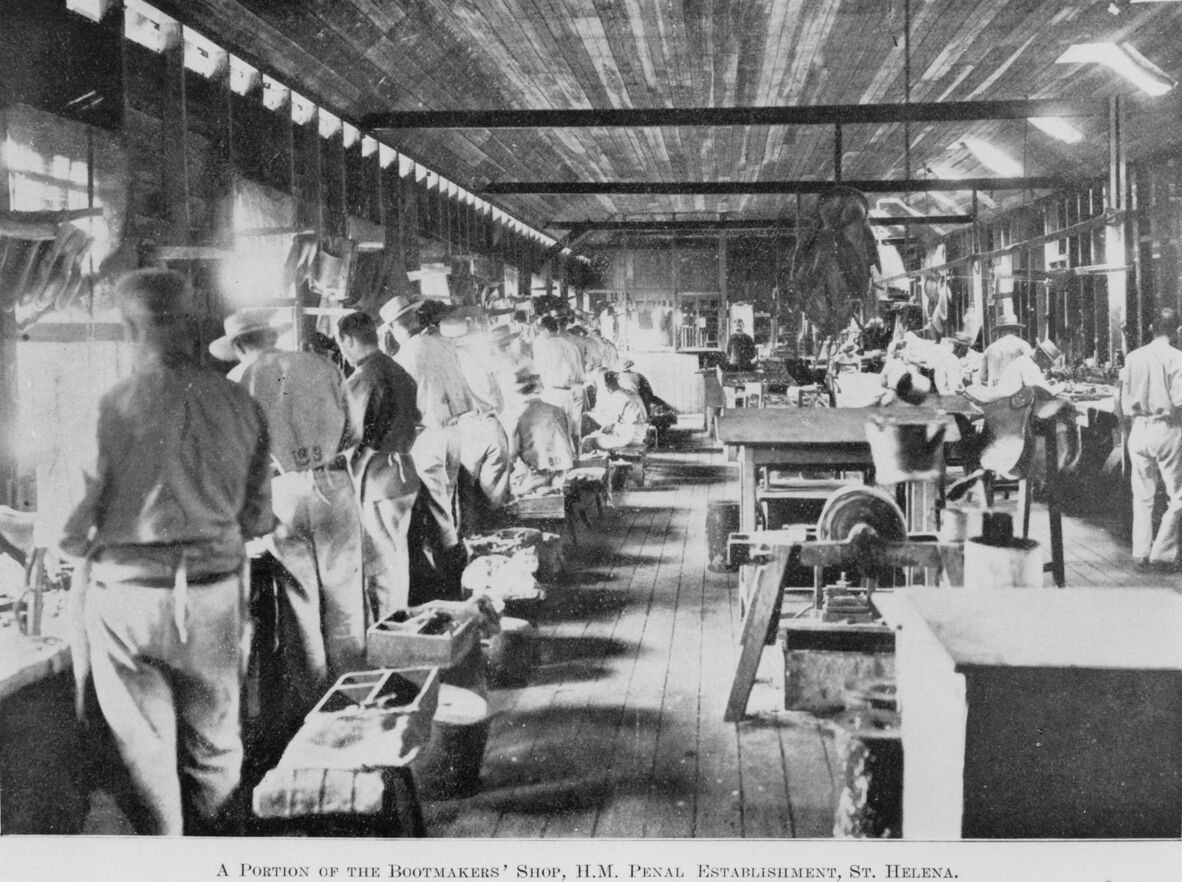

Prisoners making boots on St Helena Island, 1911. John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland, Negative number: 67111

In 1867, the same year that the Benevolent Asylum opened at Dunwich, St Helena Island became the place to accommodate Queensland’s criminal offenders. The new colony’s prisons were full (especially at Petrie Terrace), so commandeering an island for the purpose of keeping prisoners secure appealed to colonial administrators. Located just a few kilometers from the mouth of the Brisbane River, St Helena became a high-security prison. The men, dressed in easily visible white uniforms, were labourers for the many buildings, roadways and enterprises at the prison. The convicts constructed two cell blocks, a kitchen, bakehouse, hospital, underground tanks, stables, boathouse, storehouse, jetty and Superintendent’s home. In 1869, the lime kiln and sugar mill were added. Sugarcane growing and processing was part of the prisoners’ daily tasks. Later, there were boot making, sail making, tailoring, saddle making, tin smithing, candle making, book binding and carpentry workshops that were supervised by tradesmen in the relevant field, ensuring quality and productivity.

Conditions were harsh for the inmates, including silence when confined to cells. Prison reform and humane treatment of prisoners were concepts that were yet to reach Moreton Bay. Prisoners were chained when transported on the SS Otter. However, the prison was self-sufficient in food and other requirements, and there were very few escape attempts given the mangroves and deep shark-infested channels of the surrounding waters.

Sugar mill ruins on St Helena Island, 1928. John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland, Negative number: 60066

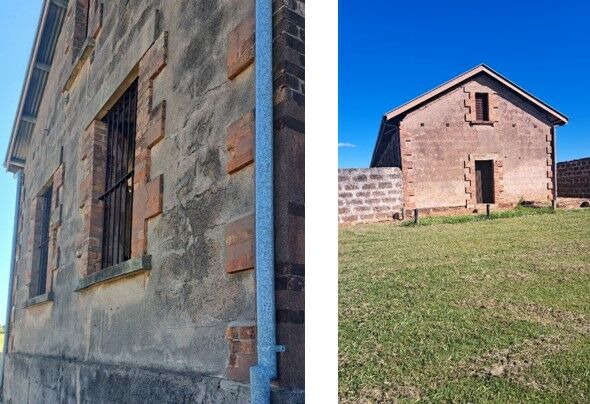

Bricks were made from clay on the island, or beach rock and timber was bought over by boat. The solid construction of building on St Helena is demonstrated by the fact that a small percentage of the buildings still stand, despite years of neglect following the closure of the prison in 1932. For many years cattle roamed the island. The prisoners raised Ayrshire cows, which won awards at the Brisbane RNA Exhibition. After the closure of the prison, the 166 acres of the island were leased as a dairy farm until 1973. It became a National Park in 1979.

St Helena had its own horsedrawn tram, supposedly the first passenger tram in the colony, which provided prisoner transport from boat to stockade. There was also a mechanical tramway in later years that took goods from the jetty to the store.

Horsedrawn tram on St Helena Island, 1928. John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland, Negative number: 1211

Colonial Secretary’s Correspondence – the warders and staff of the St Helena Prison

Warders and staff and, in some cases, their families, also lived on the island. There were warders’ barracks outside the stockade, and cottages for married couples where they could raise their children on the island. The Colonial Secretary’s correspondence shows that a schoolteacher was appointed for the warders’ children and provides a wealth of information about the staff and their circumstances of appointment, regulations and tasks.

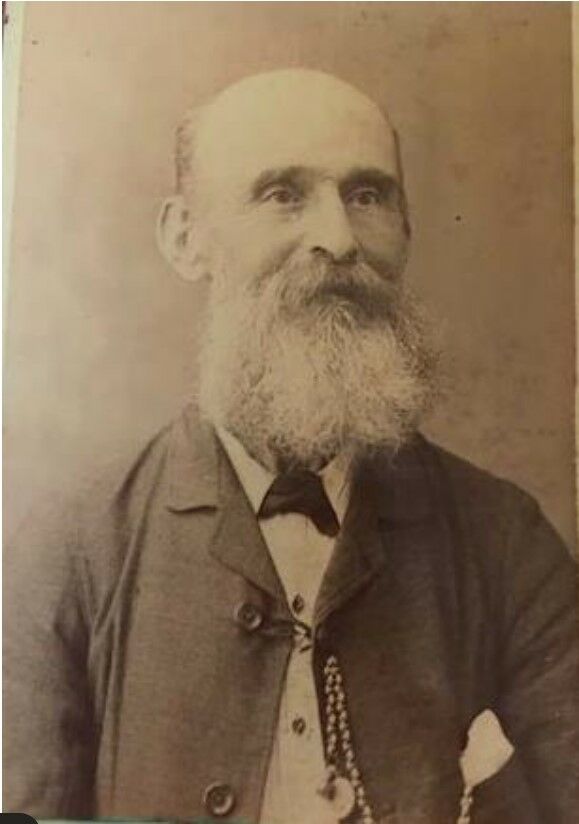

An example of St Helena staffing is Mr Robert Laws, who arrived in Queensland in 1884 and was appointed to the position of clerk and storekeeper at the St Helena penal establishment. He was accompanied by his wife and 4 daughters. He was appointed on 1 October 1884 at £150 per annum. He resigned his position of store keeper on 3 March 1885, finding it a harsh and difficult environment for him and his family. One of the daughters, Mary (later Hockings), told her children about living at St Helena for a brief time as a young teenager, going to school on the island and travelling to the island by ferry.

As an elderly gentleman, Robert Laws was not fit enough for the St Helena prison but travelled north to Townsville where he was a wardsman at the Townsville Immigration Depot and later Superintendent of Keppel Bay Quarantine Station, where he worked until 1895.

Robert Laws. Image from Ancestry database.

Robert Laws’ resignation letter of 3 March 1885 to SW Griffith shows that life on St Helena was not easy.

Sir,

Finding the duties of Storekeeper at St Helena Penal Establishment too heavy to carry on successfully for any length of time by reason of my health and strength being not equal to the task, I deem it advisable to tender to you my resignation. I do so with great reluctance but feel that by prolonging my stay in my present capacity I should only be impairing my health and ruining my constitution, I therefore most respectfully beg of you to transfer me to some other post. I have no desire to quit my present one until you are suited with my successor. Captain Townley has expressed himself well satisfied with my endeavours but feels as I feel, that the duties of prison life being of a foreign nature to the ordinary duties of an office, I am unsuited to the occupation and has advised to take the step which I am now doing"

Colonial Secretary’s Correspondence, 1885. Queensland State Archives.

A new store was constructed in 1885, as the previous one was too cramped, and the prisoners’ clothes and belongings were stored in the same room as the grocery items. There were also security issues regarding who had access to the stores, and there was concern that the prisoners could access the armoury.

Goods arrived by steamer and could be transported by tramway to the store. The tramway was already in place in 1885. The new store was built and is still standing today.

Former warders’ cottages for married couples and children on St Helena, 2024. Image by Donna O’Kearney

Cell block walls still standing showing solid building methods of the 1860s. St Helena, 2024. Images by Christina Ealing-Godbold.

Peel Island (Teerk Roo Ra) – Lazaret

Six kilometres from the port of Cleveland, Peel Island also was used for the purposes of separation and quarantine. It was used as a quarantine station when the Dunwich Quarantine Station was converted to a Benevolent Institution and the neighbouring St Helena Island was made into a high security prison. In the years at the end of the 19th century, it was used as a place to house inebriates. However, leprosy had become more common in Queensland in the 1880s, and Peel Island became a leprosy station following the Leprosy Act of 1892. Although it was meant to be a medical facility for leprosy (also known as Hansen’s Disease), methods focused more on separation and enforcement than on medical treatment. Peel Island operated as a lazaret from 1907 to 1959. Visitations from family members were limited and, once again, the only transport was the government steamer.

Peel Island lazarette huts, part of the female division, 1907. The Queenslander, 3 August 1907, p 23. John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland, Negative number: 36681

There are eleven [huts] for males, and five for females, each 10 ft by 12 ft. They are lined, ceiled and ventilated. Each has a French light and a large window, and is furnished with a four-post bedstead, spring mattress, table, chair and chest of drawers”

The Queenslander, 3 August 1907, p 23.

As part of State Library of Queensland’s collections, the story of Phyllis Ebbage of Townsville tells a tale of horror of a young mother forcibly removed to Peel Island for 12 years, missing the school years of her 2 daughters. Phyllis was reunited with her family in 1951 but, despite being kept on the island in miserable conditions for more than a decade, she did not have a diagnosis of leprosy – only the suspicions of the general practitioner in Townsville.

Portrait of Phyllis Ebbage. John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland, Image number: 9997-0029-0001

Peel Island became an Environmental Park in 1989, and in December 2007 Peel Island was declared as Teerk Roo Ra (Place of Many Shells) National Park and Conservation Park. It is known for its lovely horseshoe bay that allows anchorage for small craft.

The glorious islands of Moreton Bay played a significant role in the development of the colony of Queensland. While providing a challenge for shipping and exploration, they were also used for fishing, oystering, the Dugong industry and whaling, as well as the extract of mineral sands. There are also many harsh stories of detention, separation and incarceration in this beautiful natural location.

Information on Robert Laws was provided by his great great granddaughter, Donna O’Kearney.

Further resources

- OM91-46, Dunwich Benevolent Society Clippings ca. 1920 - 1930, John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland

- 33383, Mark Wilson glass plate and photographic negatives collection, John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland

- Sketch survey maps of Benevolent Asylum, Dunwich, 1913 [originally surveyed] David Dietrichson, John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland

- Research guide to Dunwich and Eventide Records. Queensland State Archives

- OM78-04/8, ‘St Helena Penal Establishment History’ typescript, John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland

- Report from the Select Committee on the Penal Establishment at St Helena, together with the Proceedings of the Committee and Minutes of evidence. Queensland Legislative Assembly

- St Helena Island National Park management plan. Queensland National Parks and Wildlife Service.

- Sharing the waterways: Shark-proof swimming, penal detention and the early history of St Helena Island, Moreton Bay. Cathy Keys.

- 6099, Peel Island Lazaret Photographs, John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland

- 9997, Phyllis Ebbage Collection, John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland

- St Helena Island Community webpage

More information

Plan your visit – https://www.slq.qld.gov.au/visit

What’s on at State Library – https://www.slq.qld.gov.au/whats-on

Library membership – https://www.slq.qld.gov.au/services/membership

One Search catalogue – https://onesearch.slq.qld.gov.au

Ask a librarian - https://www.slq.qld.gov.au/services/ask-librarian

Comments

Your email address will not be published.

We welcome relevant, respectful comments.